Determining adverse events and their frequency for various pharmacological and other interventions is often a challenge

(1–

4). Randomized trials offer a prime opportunity for collecting not only efficacy data but also useful information on adverse events

(1–

3,

5,

6). However, empirical evaluations have shown that the reporting of safety information, including withdrawals due to toxicity, clinical adverse events, and laboratory-determined toxicity, is often neglected in randomized controlled trials of therapeutic and preventive interventions

(7–

11). These deficiencies have serious consequences, limiting the ability to understand the risk-benefit ratios of these interventions

(12), even when they prove to be effective. Previous work on safety reporting has addressed trials in various medical fields

(7–

11). There is evidence that some deficiencies are more prominent in trials from some medical areas than in others

(7). Nevertheless, to our knowledge, none of the previous evaluations has specifically targeted trials of interventions in the area of mental health. In this work, we have evaluated safety reporting in a large random sample of randomized controlled trials on various mental-health-related interventions.

Results

Characteristics of Eligible Trials

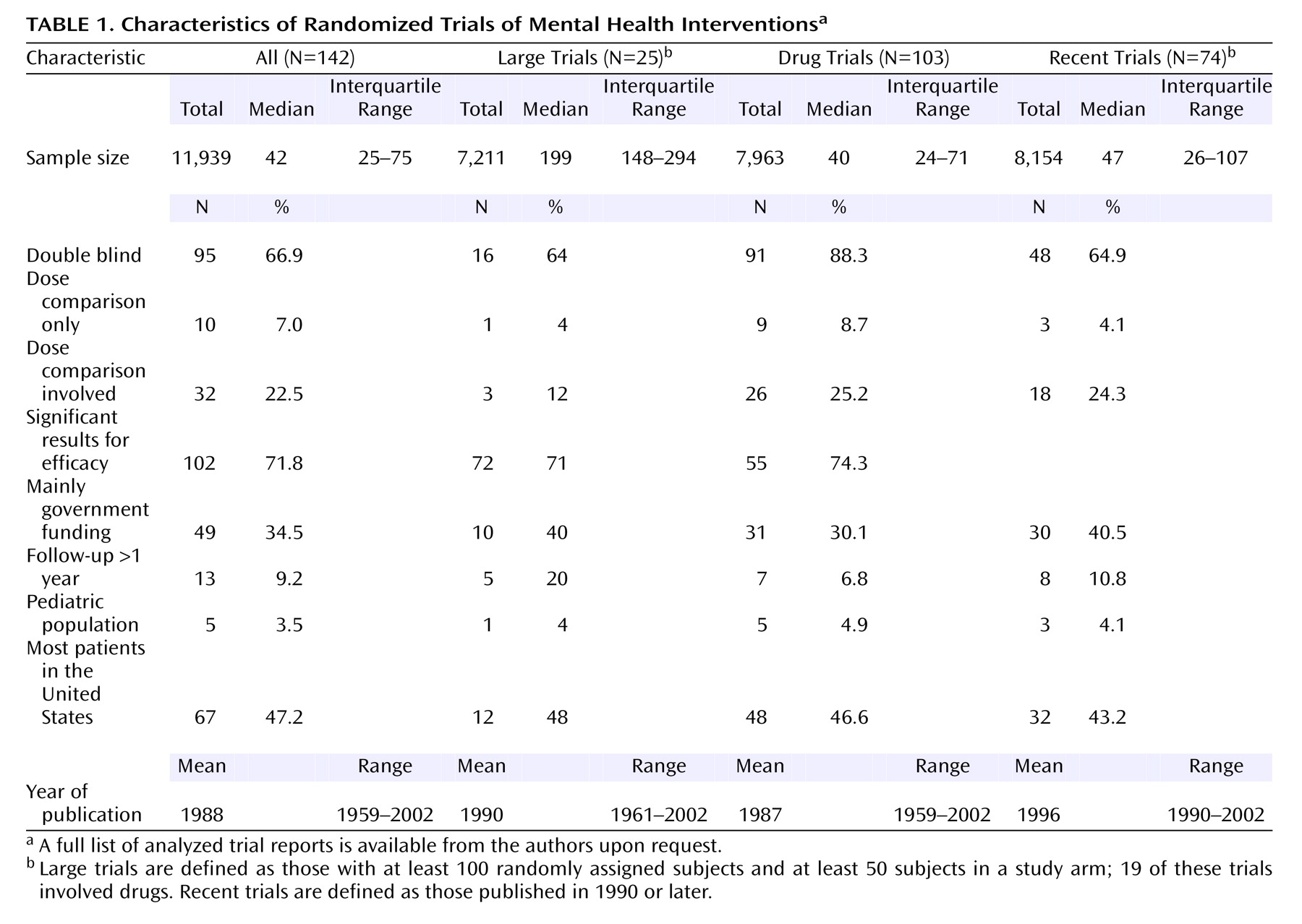

Of 200 randomly selected Psi-Tri trial entries, we excluded 22 in which none of the references had been published in journals, 44 that did not pertain to randomized trials, and two that could not be retrieved in full text. Thus, 132 reports with 142 separate randomized trials (N=11,939 subjects) were eligible for further analysis. Of those, 11 had more than one journal publication (N=48 secondary publications). Only two secondary publications provided additional safety data, on one trial each. Trials belonged to the depression, anxiety, and neurosis (N=79); developmental, psychosocial, and learning problems (N=5); dementia and cognitive improvement (N=13); schizophrenia (N=33); and drug and alcohol (N=12) domains, respectively. Of the 142 trials, 25 had at least 100 subjects and at least 50 subjects in a study arm. Drugs were involved in the randomized comparisons in 103 (72.5%) of the 142 trials (N=7,963 subjects). Of the 103 drug trials, 62 contained an arm that received only placebo or no treatment. Nondrug trials addressed other biological (N=6), behavioral (N=13), social or health services (N=11), and psychological (N=9) interventions.

Overall, studies were of small group size (

Table 1). About two-thirds of the trials were double blind, the percentages were higher among drug trials, and about a quarter involved some dose comparisons. Most trials showed statistically significant results for efficacy. About a third of the trials had received government funding. Few trials had long-term follow-up, and few involved children. Approximately half had been conducted in the United States. Trial reports covered a wide range of publication years, with half being published after 1990.

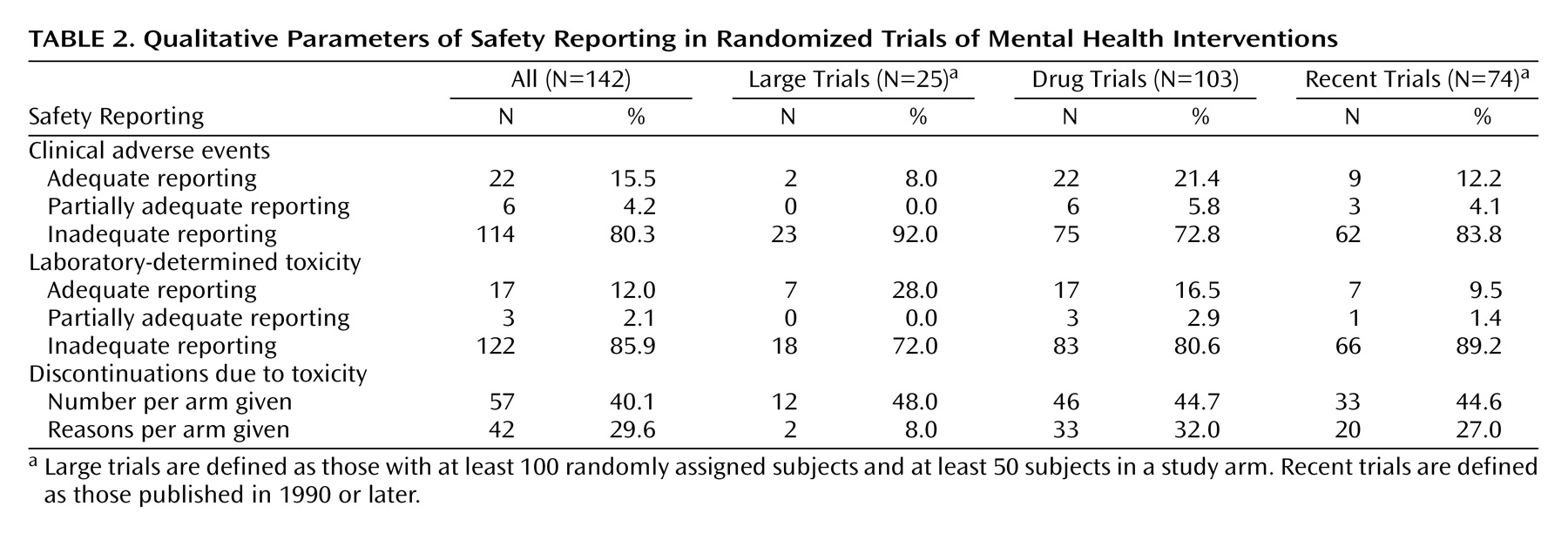

Qualitative Assessment of Safety Reporting

Overall, less than one out of six trials had adequate reporting of clinical adverse effects and even fewer trials had adequate reporting of laboratory-determined toxicity (

Table 2). Studies with at least 100 subjects and at least 50 subjects in an arm had somewhat worse documentation of clinical adverse events and somewhat better documentation of laboratory-determined toxicity. Even among drug trials, the rates of adequate reporting were very low (21.4% and 16.5%, respectively). Drug trials with placebo/no treatment arms also had very low rates of adequate reporting (17.7% and 12.9%, respectively). No nondrug trials reported adequately on clinical adverse events or laboratory-determined toxicity.

Discontinuations due to toxicity per study arm were mentioned in slightly less than half of the trials, and the percentage was not much better in trials with at least 100 subjects or drug trials. Specific reasons for these discontinuations per arm were given less frequently, and this was recorded in only 8% of the trials with at least 100 subjects and at least 50 subjects in an arm. Nine nondrug trials simply stated clearly that no subjects discontinued the trial or mentioned reasons for discontinuations that were unrelated to toxicity. Otherwise, none of the nondrug trials provided data on discontinuations occurring due to toxicity.

There was no statistically significant heterogeneity in the rates of adequate reporting across collaborative review group domains for clinical adverse events (p=0.09), laboratory-determined toxicity (p=0.28), or the two withdrawal outcomes (p=0.72 and p=0.52) (all by Fisher’s exact test).

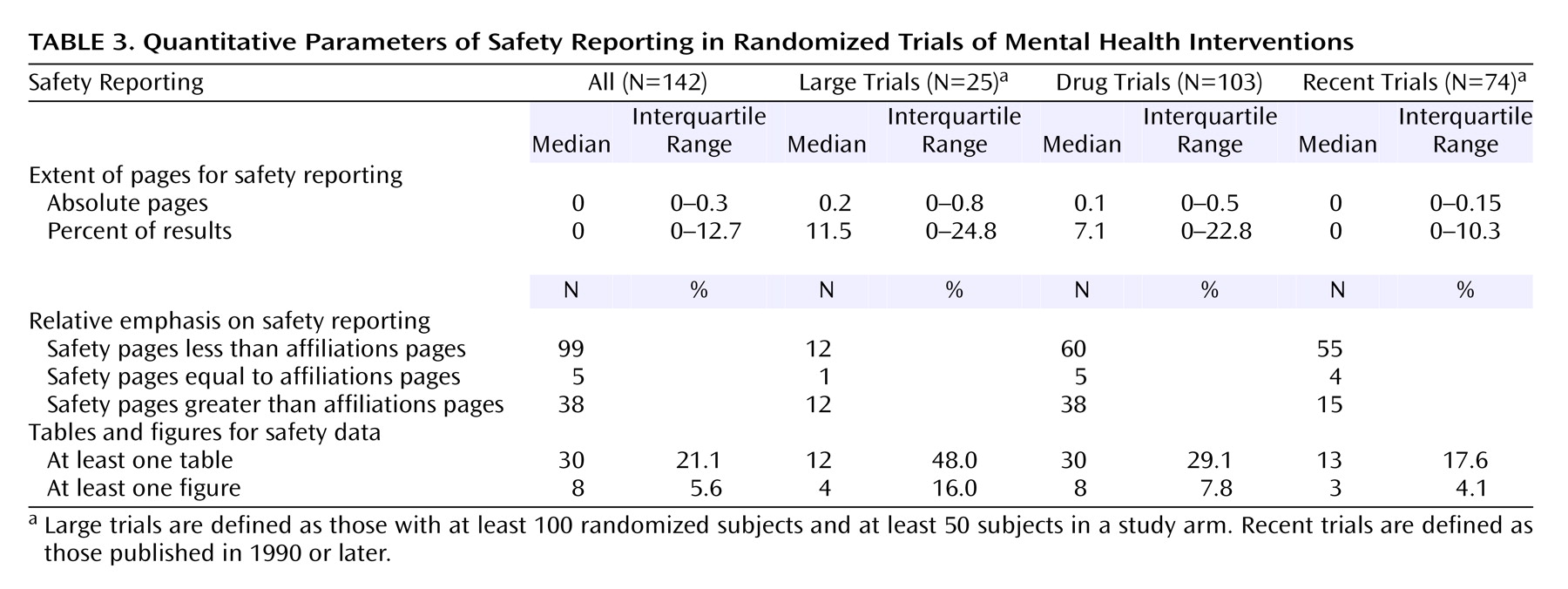

Quantitative Parameters of Safety Reporting

Little space was devoted to safety (

Table 3). Even when nondrug trials were excluded, this was on average about 1/10 of a page or even less for trials with a placebo/no treatment arm (median=0.05 page). Large trials with at least 100 subjects and at least 50 subjects in an arm used only slightly more space (median=0.15 page). Overall, the space given to safety information was less than the space given for the names of authors and their affiliations (p<0.001). The difference remained significant when analyses were limited to drug trials, while for trials with at least 100 subjects and at least 50 subjects in an arm, the space for safety was similar to the space devoted to authors and affiliations. Tables and/or figures for safety were used infrequently, and even for exclusively drug trials.

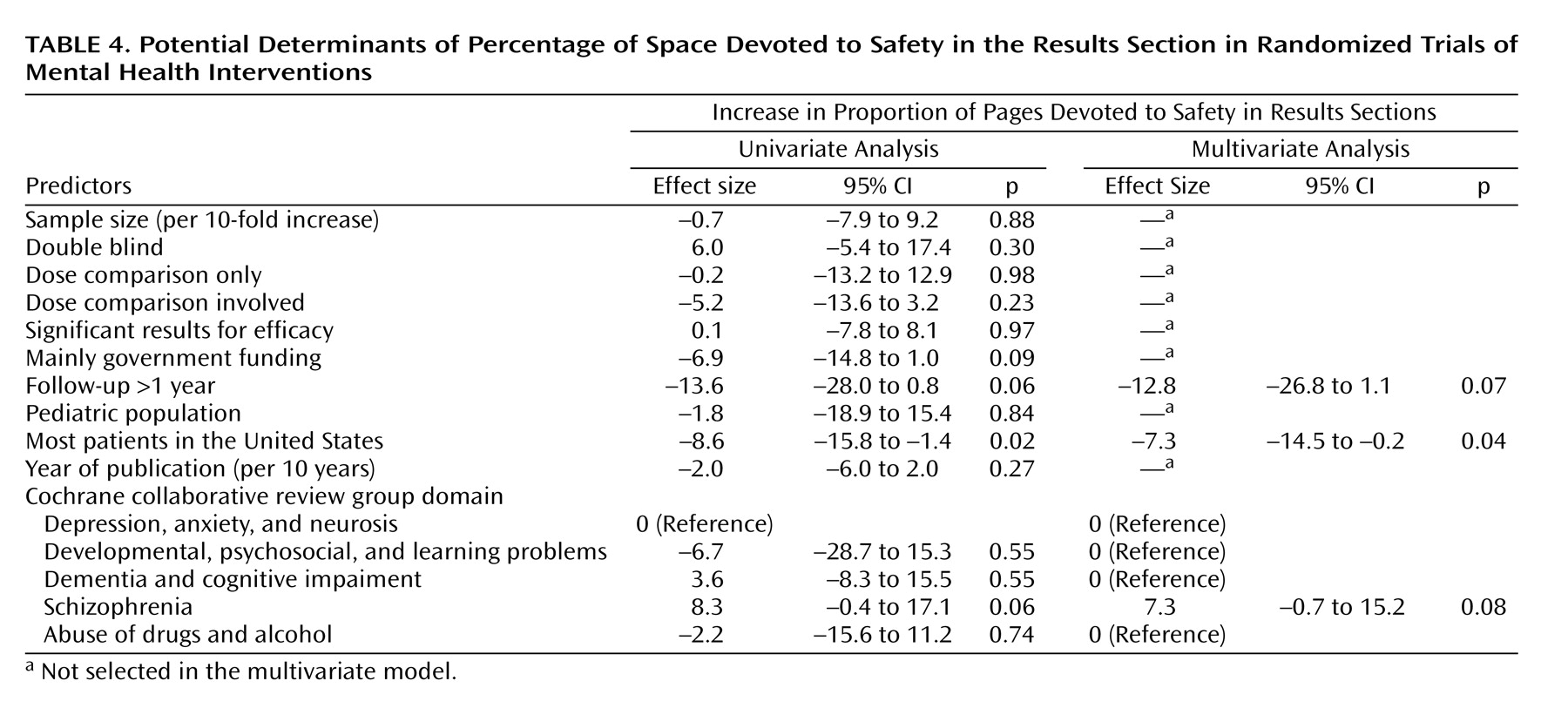

Regression Analyses

The percentage of space in the results sections dedicated to safety was significantly and independently larger in trials of schizophrenia, and it was independently smaller in trials conducted in the United States and in trials with long-term follow-up (

Table 4). Adequate reporting for clinical adverse events was more common in trials of pediatric populations and less common in trials conducted in the United States (multivariate odds ratio=8.6, 95% confidence interval [CI]=1.2–62.0, p<0.04, and multivariate odds ratio=0.3, 95% CI=0.1–0.9, p<0.04, respectively). Adequate reporting of laboratory-determined toxicity was more common in larger trials (odds ratio=3.7, 95% CI=1.1–12.5 per 10-fold increase in sample size, p<0.04), but it was not significantly affected by any other parameters. Conversely, reporting of the reasons for discontinuations due to toxicity per study arm was less common in larger trials, and it was also independently less common in studies where dose comparisons were involved (multivariate odds ratio=0.2, 95% CI=0.1–0.6, p=0.004, and multivariate odds ratio=0.3, 95% CI=0.1–0.9, p<0.04, respectively).

The quality of safety reporting did not improve in recent trials (

Table 2 and

Table 3). In logistic regression, the odds of adequate reporting of clinical adverse events, laboratory-determined toxicity, and reasons for withdrawals due to toxicity nonsignificantly changed by 0.78-fold (p=0.29), 0.86-fold (p=0.54), and 0.94-fold (p=0.76) per 10 years, respectively, while the pages devoted to safety nonsignificantly decreased by 0.05 per 10 years (p=0.29).

Discussion

Randomized trials in the field of mental health often neglect the safety aspects of the tested interventions. Even with lenient criteria, very few drug trials and practically none of the nondrug trials have adequate reporting of clinical adverse events and laboratory-determined toxicity. Trial reports devote less space to safety than to names of authors and affiliations. Most trials in this field are of relatively small sample size

(14) and may be underpowered to address safety issues, but even larger trials do not score consistently higher on all parameters of safety reporting. Very few trials in the field have long-term follow-up, and these seem to pay even less attention to safety relative to efficacy. If anything, less space has been given to safety in trials conducted in the United States, and safety reporting is not improving in more recent trials. We could not identify any parameters that have consistently led to substantially improving the reporting of both clinical and laboratory-determined toxicity as well as withdrawals.

The neglect of safety in mental health-related trials is similar and possibly worse than what has been reported for six different medical fields (HIV therapy, hypertension in the elderly, acute sinusitis, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for rheumatoid arthritis, selective decontamination of the gastrointestinal tract, and antibiotics for

Helicobacter pylori)

(7). These previous evaluations had targeted exclusively trials with at least 100 subjects and at least 50 subjects in a randomized arm. Therefore, the most direct comparison should probably involve the 25 mental health trials fulfilling these sample size criteria. Even thus, the mental health field fared worse than all six other medical fields for the reporting of reasons for withdrawals and worse than five of six other medical fields for the reporting of clinical adverse events, while reporting rates for laboratory-determined toxicity were similar to the average of the six other fields. Withdrawals are frequent in mental health-related trials, and it is important to know why they have occurred

(15).

In approximately one-quarter of the trials in our database, no drug treatments were evaluated. This constitutes a further difference between these trials and the traditional pharmacotherapy trials of many other medical domains. The consideration, let alone reporting, of adverse events in the assessment of nondrug interventions may be a challenge. Nondrug trials in our sample universally failed to report safety data. The adverse effects of behavioral, psychological, or social interventions are difficult to document and attribute to the tested intervention. However, attribution and causality is a problem even in drug trials

(16). These obstacles should not prohibit the collection of data on adverse events. It is likely that psychosocial interventions can cause adverse outcomes. Unless investigators are prepared to record adverse events, these will never become known, and potentially harmful interventions may thus become established into mental health clinical practice.

In contrast to other medical areas

(7), we found no improvement in the coverage of safety issues in trials involving dose comparisons. This is of concern since it suggests that dose-comparison trials in mental health place their emphasis unilaterally on efficacy. However, safety is an important consideration in selecting the dose or treatment schedule with the best benefit-to-harm ratio. Furthermore, the neglect of safety in long-term trials is also problematic, since long-term trials provide a key opportunity for understanding the safety of an intervention in a controlled setting with systematic recording of information. Finally, while it is encouraging that schizophrenia trials provided more attention to safety, this was true primarily for the amount of space and not for the quality of the information. Adverse events may be relatively more important in other mental diseases, which are less devastating than the major psychoses.

The neglect of safety reporting in randomized trials has implications for the conduct of evidence-based health care. Data suggest that not only clinical trials but also systematic reviews place little attention on toxicity

(17,

18). Despite the fact that patients are usually poorly informed or unaware of even major adverse effects of the drugs that they are taking

(19), patients would ideally wish to know a lot about potential toxicity, no matter how rare, before making therapeutic or preventive choices

(20).

Some potential limitations should be discussed. We selected a random sample of trials from a registry that does not yet contain all mental-health-related trials. However, the registry coverage at the time of sampling probably exceeded 90%. Second, our sample included mostly small studies. Investigators may feel that small studies cannot make a meaningful contribution toward estimating the risk of uncommon or even common toxicities. However, the conduct of small studies is no justification for neglecting safety. For many interventions, only small trials will ever be performed. Third, it is difficult to reach a consensus on what constitutes an adequate reporting of safety. Space alone does not guarantee that important information is conveyed properly. We used standardized definitions that have been previously validated in other fields and that allowed comparisons with other medical areas. Qualitative and quantitative measures should provide complementary insights. Still, we encourage the further development of evaluation tools that would focus on appraising safety reporting in specific categories of trials, besides more generic tools

(21). Nondrug trials in mental health are one area where such alternative tools would be particularly useful to develop. Fourth, some information on safety outcomes may be impossible to disentangle from efficacy outcomes. Mental health outcomes are often the integral composite of benefit and toxicity. Nevertheless, serious and life-threatening toxicity should be possible to record separately in most situations.

Finally, it is impossible to decipher whether the lack of safety information in a published article reflects the fact that such information was never collected or was collected but not reported. Given the fact that safety data are hard to retrieve after the trials are published

(22), we strongly recommend that standardized reporting should be adopted

(6,

23), with appropriate attention to toxicity. An extension of the CONSORT statement

(23) for harm is currently being prepared. Information to contributors’ pages in mental health journals should emphasize the importance of covering information of potential harm in adequate detail with emphasis on serious and severe events and withdrawals per study arm.