Over the last several years, a number of federally funded health promotion initiatives have sought to improve the recognition and management of depressive disorders in primary care

(1–

3). Routine screening for depression is now recommended in primary care practices that have the capacity to provide effective management

(1). In relation to the attention devoted to the diagnosis and treatment of unipolar depression, much less effort has been given to the management of primary care patients who have current depression and past episodes of mania or hypomania. A history of manic symptoms in patients with current depression may signal bipolar disorder and a need to consider pharmacological treatments aimed at mood stabilization

(4,

5).

Patients who have bipolar disorders typically come to primary care during an episode of depression

(6,

7). In a large longitudinal study of adults with bipolar disorder

(8), patients were in a predominantly depressive phase of illness more than three times longer than they were in a predominantly manic/hypomanic phase of illness. Because primary care physicians seldom inquire about symptoms of mania, a history of mania or hypomania can be easily missed during the course of routine care

(9).

The clinical distinction between bipolar and unipolar depression has important implications for pharmacological management. Although antidepressant medications are widely recognized as a first-line treatment for major depressive disorder

(10–

12), the proper role of antidepressant medications in bipolar depression remains controversial

(13,

14). A recent record review of psychiatric outpatients

(14), for example, revealed that compared with unipolar depression, bipolar depression was associated with an increased risk of antidepressant nonresponse, manic switching, cycle acceleration, and loss of antidepressant response. By contrast, relapse after discontinuation of antidepressant medication was significantly more common in unipolar than bipolar depression

(14). Because a wide range of antidepressant medications are believed to precipitate manic episodes

(15–

17), several practice guidelines specifically caution against the treatment of bipolar depression with antidepressant monotherapy

(5,

18,

19).

The current study compares the background sociodemographic, clinical, and treatment characteristics of adult primary care patients with major depressive disorder who either did or did not screen positive for a history of bipolar disorder. We sought to determine whether patients who have bipolar depression, defined as current major depression and a positive screen for a lifetime history of bipolar disorder, tended to appear with different symptoms or impairments than those with unipolar depression. If patients with bipolar and unipolar depression have different clinical presentations, this information could be used to alert primary care physicians to the need for referral to a psychiatrist before they initiate pharmacological treatment. We also evaluated the extent to which patients with bipolar depression from the practice under study were treated with antidepressant medications without antipsychotic medications or mood stabilizers.

Method

The study was conducted at the Associates in Internal Medicine practice of New York–Presbyterian Hospital (Columbia University Medical Center). Associates in Internal Medicine is the faculty and resident group practice of the Division of General Medicine at the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Columbia University. Associates in Internal Medicine provides primary care to approximately 18,000 adult patients from the surrounding northern Manhattan community each year.

The institutional review boards of Columbia Presbyterian Medical Center and the New York State Psychiatric Institute approved the study protocol, including the Spanish translation of data forms. All participants provided informed consent.

Participant Recruitment

A systematically selected group of consecutive adult patients seeking primary care at the Associates in Internal Medicine practice were invited to participate. The patients were approached to determine eligibility based on the seat they freely selected in the practice waiting rooms. Eligible patients were ages 18 to 70 years, had made at least one prior visit to the practice, could speak and understand Spanish or English, and were waiting for scheduled face-to-face contact with their primary care physician. Patients were excluded from the study if their current health status prohibited completion of the survey forms.

Because one aim of the study was to examine clinical detection and management of primary care patients with bipolar depression, we sought to limit the group to returning patients because these patients were likely to be better known to the primary care physicians than patients making their first clinic visit. There was also a concern that because of the substantial patient burden of the routine clinical intake procedures, patient fatigue during the first visit might compromise the quality of the research assessment.

The study focused on patients scheduled to see their primary care physician. We excluded the substantial number of waiting room patients who were scheduled to see other health care professionals. Examples of such patients included patients treated with oral anticoagulation therapy who were scheduled for prothrombin time measurements, patients scheduled to see nurse practitioners for routine Pap smears, and patients of a memory disorders clinic, a podiatry clinic, and other subspecialty clinics that share waiting rooms with the primary care practice.

A total of 3,807 patients were approached, 169 of whom (4.4%) refused solicitation. Of the 3,638 who were prescreened, 2,291 (63.0%) were ineligible to participate. Inclusion criteria most frequently unmet were 1) not being scheduled for face-to-face contact with a primary care physician (56.5%), 2) not being between 18 and 70 years old (33.5%), and 3) not having made a previous visit to the practice (16.7%). Less commonly, patients were excluded because they were unable to complete the survey forms because of poor physical health (3.3%) or cognitive impairment (1.6%). Of the 1,347 who met the eligibility criteria, 1,157 (85.9%) consented to participate, and of these, 1,143 (98.8%) provided sufficient information to be classified with respect to the Mood Disorder Questionnaire, a brief self-report assessment of lifetime bipolar disorder (20).

Sociodemographic and Clinical Assessment

The survey forms were translated from English to Spanish and back-translated by a bilingual team of mental health professionals. All participants completed a sociodemographic history form to assess age, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, educational achievement, and annual household income. The participants also completed the Mood Disorder Questionnaire, a 15-item self-report assessment of lifetime bipolar disorder based on DSM-IV criteria (20). The standard Mood Disorder Questionnaire scoring for bipolar disorder requires endorsement of ≥7 total lifetime manic symptoms with two or more co-occurring symptoms resulting in moderate or serious functional impairment

(20,

21). At this cutoff point, the Mood Disorder Questionnaire was reported to have a sensitivity of 0.281 and a specificity of 0.972 in a community sample (20) and a sensitivity of 0.73 and a specificity of 0.90 in an outpatient psychiatric sample

(21) with a Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID)

(22) diagnosis of bipolar I and bipolar II disorders as the criterion standard. In the current analysis, the participants who met or exceeded the standard Mood Disorder Questionnaire scoring algorithm were considered to have screened positive for a lifetime history of bipolar disorder.

The DSM-IV Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders (PRIME-MD) Patient Health Questionnaire

(23) was used to assess current symptoms of major depression, panic disorder, general anxiety disorder, and past-year alcohol use disorder. Drug use disorders were assessed with a module patterned after the PRIME-MD alcohol use disorder module.

Health functioning was evaluated with the physical and mental health component summary scores of the Medical Outcomes Study 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey

(24). Impairment was evaluated with the 10-point self-rated social life and family life/home responsibilities subscales of the Sheehan Disability Scale (0=none, 1–3=mild, 4–6=moderate, 7–9=marked, 10=extreme)

(25). Because only 12.4% of the study patients were gainfully employed, the work subscale of the Sheehan Disability Scale was not used. Items from the psychotic disorders section of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview

(26) were administered to assess lifetime and current history of hallucinations.

Self-report information was collected concerning mental health treatment history, including lifetime hospitalization for psychiatric care and past-month use of antidepressant, antimanic, and antipsychotic medications.

Analytic Strategy

The patients with current DSM-IV/PRIME-MD major depressive disorder were first partitioned on the basis of Mood Disorder Questionnaire screening status into those with unipolar (negative screening on the Mood Disorder Questionnaire) and bipolar (positive screening on the Mood Disorder Questionnaire) depression. These two patient groups were compared with respect to sociodemographic characteristics, depressive symptoms, comorbid mental disorders and symptoms, health functioning, and mental health treatment, including use of antidepressant, antipsychotic, and antimanic medications. Comparisons between patient groups on categorical variables were made with the chi-square test, except when the expected count fell below 5 in at least 20% of the cells, in which case, Fisher’s exact test was used. Student’s t test was used for comparisons involving continuous variables. The alpha was set at 0.05 (two-tailed).

Results

Sociodemographic Characteristics

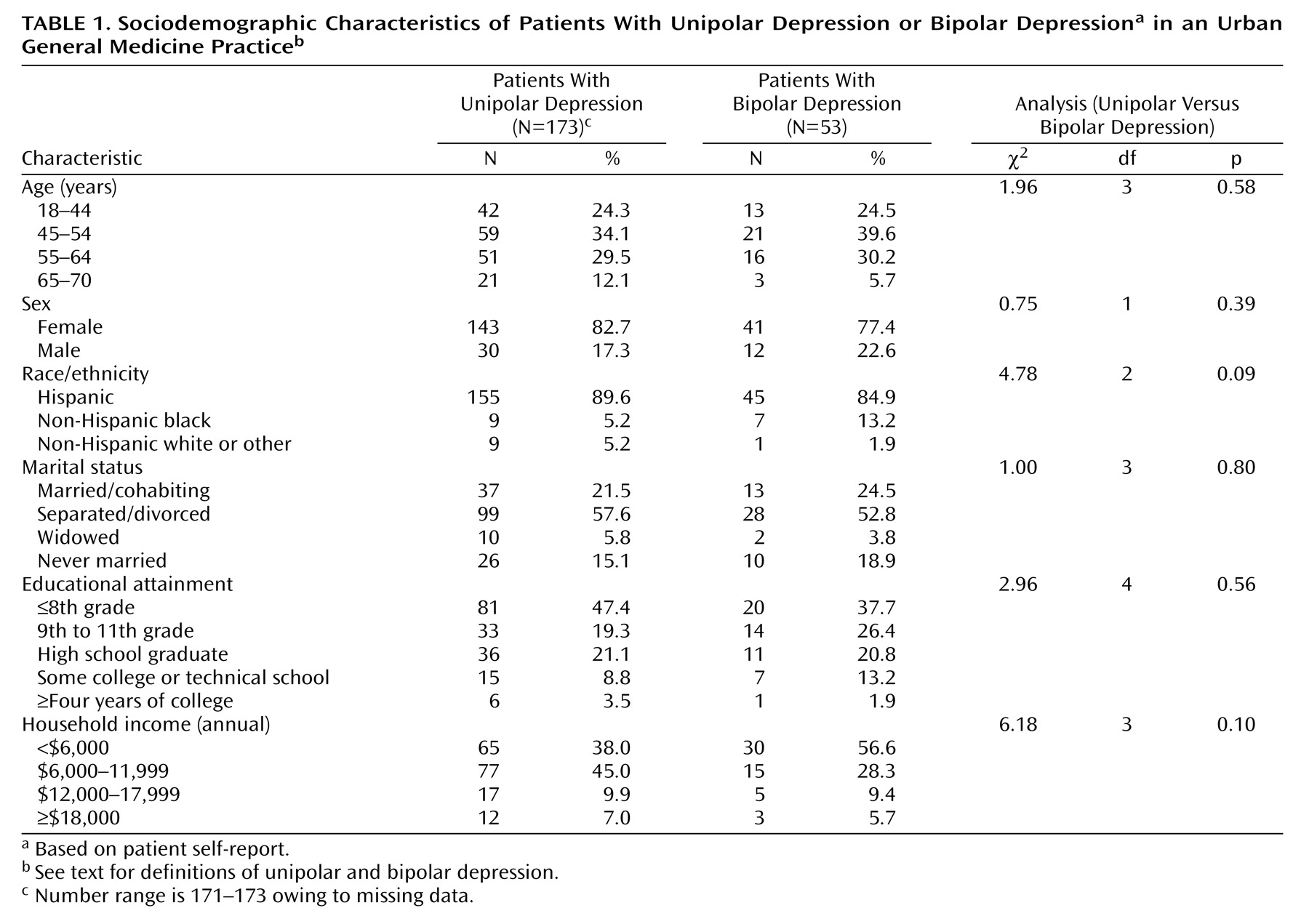

In the study sample (N=1,143), the prevalence of unipolar depression was 15.1% (N=173), and the prevalence of bipolar depression was 4.6% (N=53). Both groups were predominantly women, Hispanic, not married or cohabiting, had received less than a high school education, and had a total family income of less than $12,000 per year. There were no significant group differences in age, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, educational attainment, or household income (

Table 1). In addition, 23.5% (N=53) of the patients with current major depression were classified as having bipolar depression, and 76.5% (N=173) were classified as having unipolar depression.

Psychiatric Symptoms and Mental Disorders

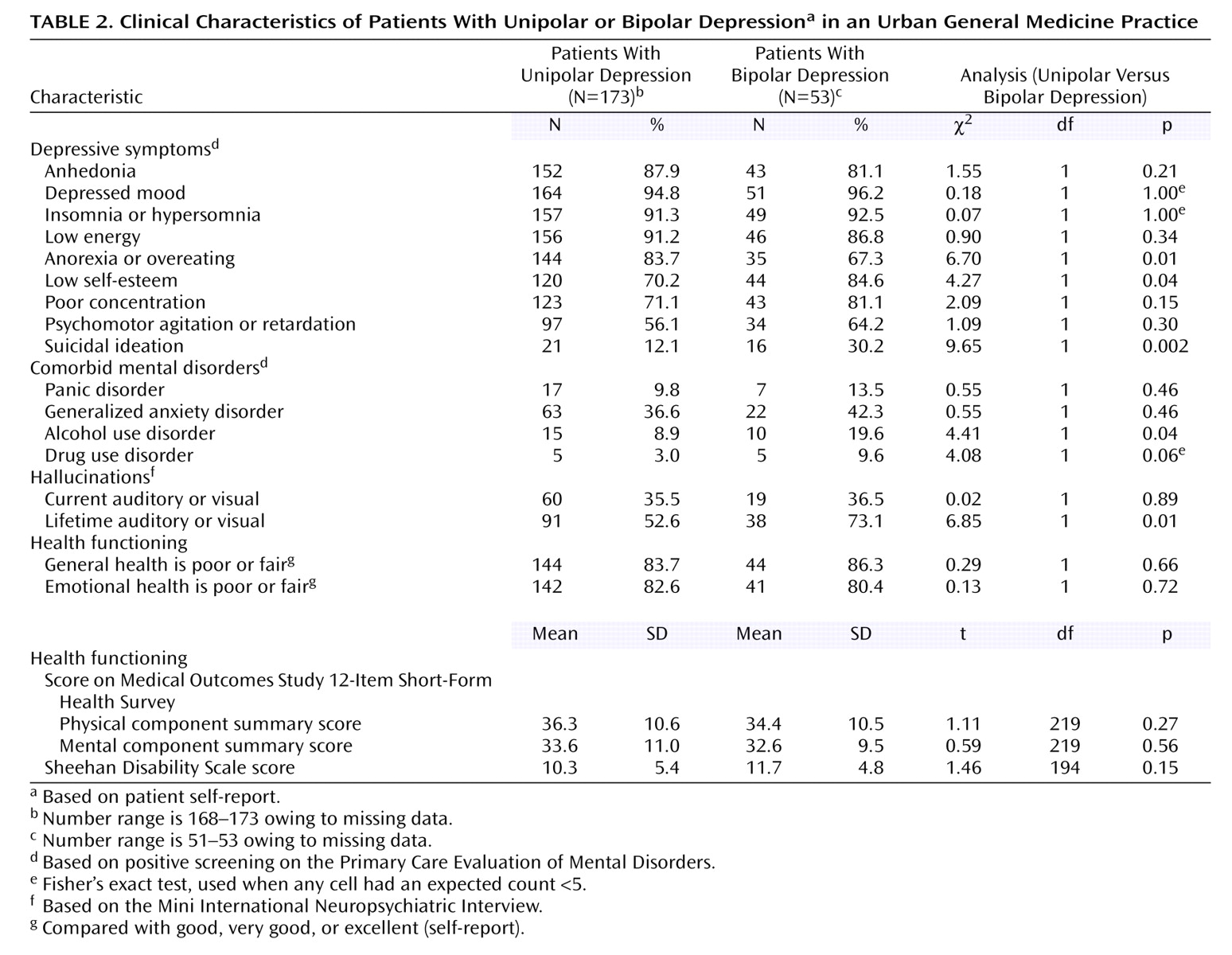

The study groups were compared with respect to the frequency of current depressive symptoms, defined as occurring on one-half or more of the days during the past 2 weeks, and for suicidal ideation on any days during the past 2 weeks. Compared with the patients with unipolar depression, the patients with bipolar depression were significantly more likely to report low self-esteem and suicidal ideation but were less likely to report an appetite disturbance (

Table 2).

Comorbid generalized anxiety disorder occurred in more than one-third of each group. In addition, the patients with bipolar depression were significantly more likely than their counterparts with unipolar disorder to meet criteria for current alcohol use disorder and to report a lifetime history of auditory or visual hallucinations (

Table 2).

Health Functioning

A substantial majority of the patients with bipolar and unipolar depression reported that their current general health and mental health were fair or poor rather than good, very good, or excellent. There were no significant group differences on the two-factor Sheehan Disability Scale score or on the physical or mental health components of the Medical Outcomes Study 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey (

Table 2). For both groups, the Medical Outcomes Study 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey scores reflected substantially lower health-related quality of life than general community samples

(27).

Mental Health Care

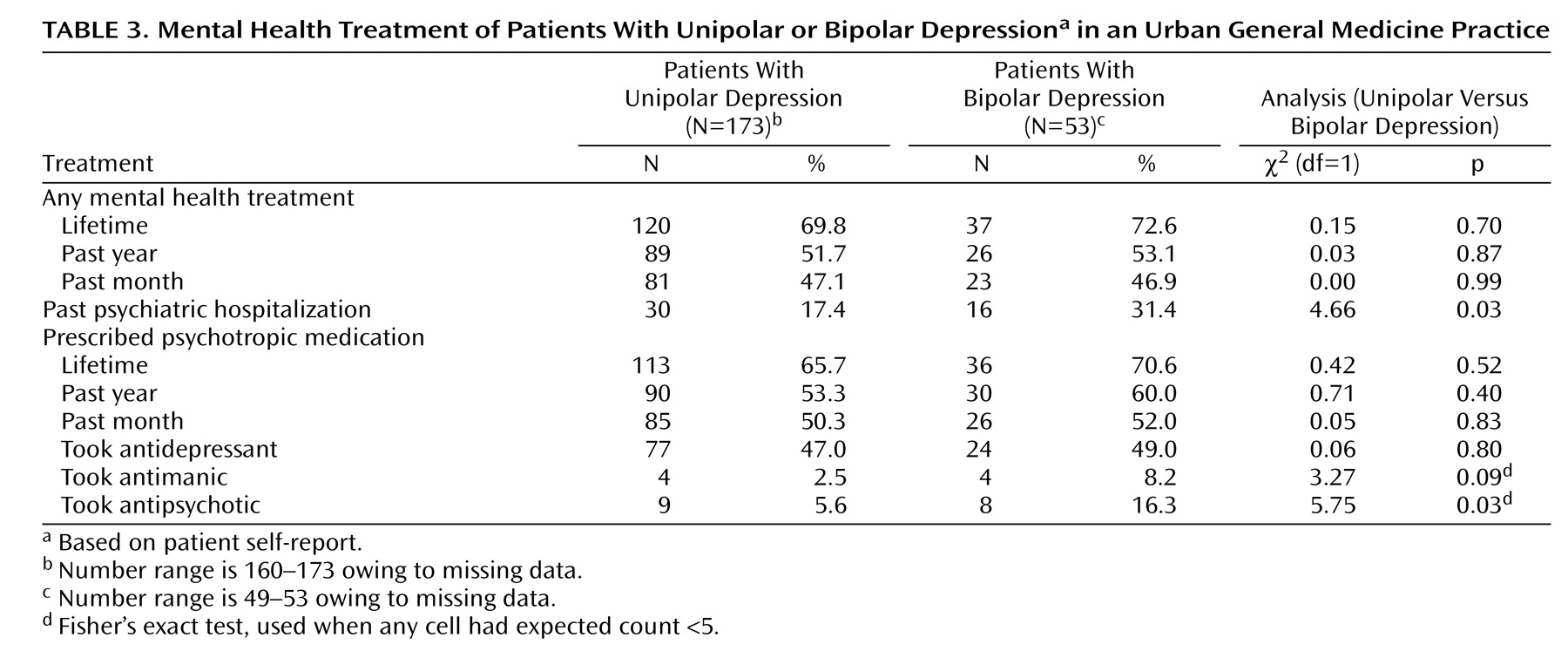

Roughly one-half of the patients with bipolar depression and unipolar depression reported having been given a prescription for a psychotropic medication in the last month. In both groups, antidepressants were the most frequently reported psychotropic medication, followed by antipsychotic and antimanic medications. During the past month, a significantly greater proportion of bipolar than unipolar patients were treated with an antipsychotic medication (

Table 3). However, most of the patients with bipolar depression (N=17, 70.8%) who were treated with antidepressant medications were not concurrently treated with either an antipsychotic or antimanic medication.

The patients with bipolar depression were significantly more likely than the patients with unipolar depression to report a past psychiatric hospitalization (

Table 3).

Discussion

In an urban general medicine practice that serves a predominantly low-income immigrant population, approximately one-quarter of the patients with current major depressive disorder screened positive for a lifetime history of bipolar disorder. This represented 4.6% of the participating patients. In a previous study

(28), 2.8% of the adult patients in a suburban private family practice center with an anxiety or depressive disorder had a history of bipolar I disorder, and 18.5% had a history of bipolar II disorder.

In the current study, adult outpatients with bipolar depression (a positive screening for current major depression and lifetime for bipolar disorder) were more likely than those with unipolar depression to report suicidal ideation, low self-esteem, a comorbid alcohol use disorder, and a lifetime history of hallucinations and inpatient psychiatric care. Suicidal behavior

(29–

31), substance use

(8), psychotic symptoms

(8), and a history of inpatient psychiatric treatment

(32) have been previously reported to be common in patients with bipolar disorder. The observed constellation of clinical characteristics in the current study provides construct validity for the Mood Disorder Questionnaire, which was used to screen for lifetime bipolar disorder. However, because each of these characteristics is nonspecific, none could be used to establish a lifetime diagnosis of bipolar depression.

Approximately one-half (49.0%) of the patients with bipolar depression reported recent treatment with an antidepressant medication. Roughly similar rates of use of antidepressant medications among bipolar patients has been reported in a large voluntary registry of adults with bipolar disorder

(33) during the month before registration (57.1%) as well as for those from a national sample of bipolar patients treated in office-based psychiatric practice (45.7%)

(34).

A majority of the patients with bipolar depression who were treated with antidepressant medications did not receive concurrent treatment with a mood stabilizer or an antipsychotic medication. Because treatment with antidepressants without mood stabilizers or antipsychotic medications may destabilize patients with bipolar disorder

(35,

36), antidepressants alone are not a recommended treatment for bipolar disorder

(5,

18,

19). However, there is a role for antidepressants as an adjunctive treatment in bipolar depression. For example, treatment of bipolar depression with a combination of an antidepressant (fluoxetine) and an antipsychotic (olanzapine) is more effective than treatment with an antipsychotic alone

(37). In depressed bipolar patients with low serum lithium levels (≤0.8 meq/liter), antidepressants may also confer some benefit, although antidepressants do not appear to be useful adjunctive agents in depressed bipolar patients maintained on higher lithium levels

(36). Well-controlled trials also support the use of lamotrigine

(38) and lithium

(19) as monotherapies for bipolar depression.

The current study has several limitations. First, the study was conducted in an urban general medical practice that serves a predominantly low-income urban immigrant population, so the findings may not generalize to primary care settings that serve other socioeconomic populations. Second, the study excluded several patient groups that may limit the generalizability of the findings and introduce selection biases into the estimated prevalence and clinical characteristics of bipolar depression in this clinic. Because patients over 70 years of age were excluded, the results cannot be safely extended to older adult primary care patients. Systematically excluding patients not scheduled to see their primary care physician and patients there for their first visits may have further biased the study results. If, for example, patients with bipolar disorder were overrepresented among patients having their first visit because of disorder-related interruptions in continuity of care, this exclusion would reduce the estimated prevalence of bipolar depression. Third, the lifetime bipolar disorder screening was based on self-reports of past symptoms rather than expert-administered diagnostic interviews of current and past symptoms that would have likely yielded more accurate clinical information. Fourth, it is not possible with the administered instruments to distinguish bipolar I from bipolar II depression. Finally, the mental health treatment data were based on self-reports rather than administrative or pharmacy records that would likely have provided a more accurate representation of the actual use of mental health services.

In an urban general medicine practice, evidence of a lifetime history of bipolar disorder was relatively common among adult patients with current major depressive disorder. Although patients with bipolar depression had some indications of greater illness severity, they did not report significantly more impairment. Because it may be difficult to distinguish patients with bipolar depression from unipolar depression during the routine delivery of primary care, a careful systematic assessment of lifetime manic symptoms is urged before the initiation of antidepressant medications for all patients presenting with a current major depressive episode.