Executive functioning includes the processes that supervise the operation of other cognitive processes, such as inhibiting actions, restraining and delaying responses, attending selectively, setting goals, planning, and organizing, as well as set-maintaining and set-shifting, located primarily in the prefrontal cortex. Studies by our group

(2–

4) examined executive functioning in eating disorders, focusing on set-shifting tasks. Set-shifting involves the ability to move back and forth between tasks, operations, or sets

(5). Using selected perceptual and cognitive tasks, our group

(3) found that individuals with anorexia nervosa took significantly longer to “shift set” than subjects with similar IQ who did not have anorexia nervosa. Some difficulty in set-shifting persisted in women who had recovered from anorexia nervosa

(4), suggesting that set-shifting difficulties are not purely a function of the acute illness state. The hypothesized association between set-shifting difficulties and anorexia nervosa have face validity in that individuals with anorexia nervosa are often described as persistent, with rigid, conforming, or obsessional personalities

(6,

7).

An endophenotype linked to heritable etiological factors must fulfill several criteria: it must be state-independent; it must associate with illness and co-segregate within families; and it must be found at a higher rate in nonaffected family members than in the general population

(1). If a characteristic fulfills these criteria but is not proven to be heritable, it is termed a “biological marker.” Our previous work indicated that the set-shifting abnormalities in anorexia nervosa were independent of the stage of illness

(4). Thus, the primary aim of this study was to examine whether unaffected first-degree relatives (sisters) shared this pattern of neuropsychological impairment. We used the same test battery as in the previously reported study, and our subjects were women with anorexia nervosa, their healthy sisters, and healthy comparison women of similar age and IQ. We tested whether healthy sisters demonstrated set-shifting characteristics at a higher rate than the healthy unrelated women, and we tried to replicate, with a broader battery, the finding that these abnormalities are independent of acute illness state.

Results

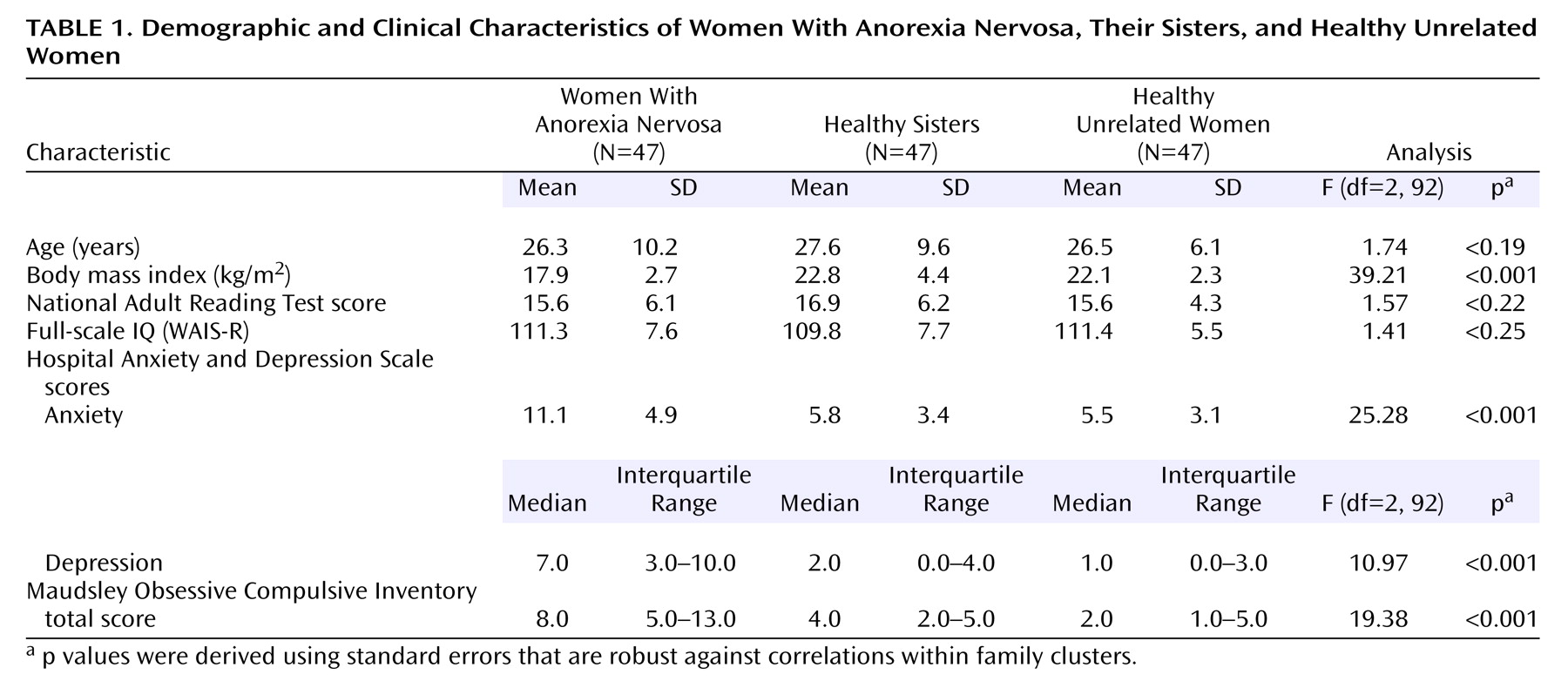

The women with anorexia nervosa, their healthy sisters, and the healthy unrelated women were well balanced in age and IQ (

Table 1). The women with anorexia nervosa had a wide range of illness duration (median=6.0 years, interquartile range=3.0–9.0). The median age at onset for anorexia nervosa was 16.0 years (interquartile range=13.0–19.0). The median lowest reported body mass index was 13.5 (interquartile range=11.9–14.9), indicating that the majority of the women had experienced a severe form of anorexia nervosa. The women with anorexia nervosa obtained significantly higher depression, anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive symptom scores than their healthy sisters and the healthy unrelated women (

Table 1).

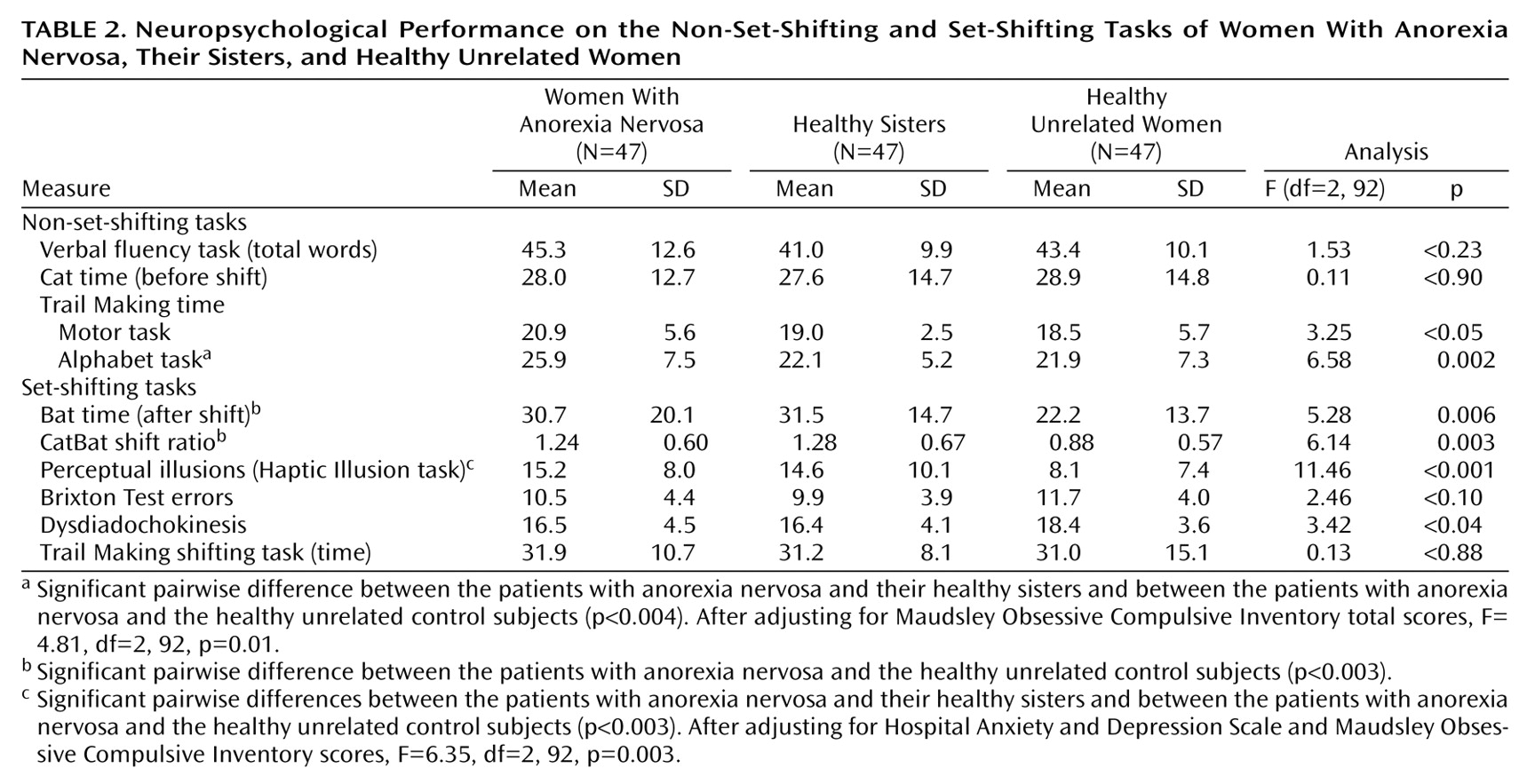

Anxiety and depression scores on the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale and scores on the Maudsley Obsessive Compulsive Inventory did not correlate with scores on the CatBat task, the Brixton Test, the neurological test for dysdiadochokinesis, or the Trail Making shifting task (all Pearson correlation coefficients below 0.20 in absolute value); therefore, unadjusted results are presented for these variables (

Table 2). The number of perceptual illusions was positively correlated with depression score on the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (r=0.27, N=141, p=0.001) and total score on the Maudsley Obsessive Compulsive Inventory (r=0.27, N=141, p=0.002). Total score on the Maudsley Obsessive Compulsive Inventory was also correlated with response time on the Trail Making alphabet task (r=0.26, N=141, p=0.004). Maudsley Obsessive Compulsive Inventory scores and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale depression scores, therefore, were considered covariates, as appropriate, for the number of perceptual illusions and response time on the Trail Making alphabet task.

The three groups were equivalent in verbal fluency and did not differ on the nonshift component of the CatBat task. Compared with their healthy sisters, the women with anorexia nervosa took significantly longer to complete the alphabet component of the Trail Making task (estimated difference=3.8 seconds, 99% CI=1.0 to 6.6) (t=3.55, df=92, p=0.001 [unadjusted]; t=3.17, df=92, p=0.002 [adjusted]) and showed a similar but statistically nonsignificant delay on the motor component (estimated difference=2.0 seconds, 99% CI=–0.1 to 4.1) (t=2.5, df=92, p<0.02). The same directional effect was observed in a comparison of the women with anorexia nervosa and the healthy unrelated women, but these differences did not reach significance when the Bonferroni-adjusted significance level of 0.003 was applied (motor component: 2.4 seconds, 99% CI=–0.7 to 5.5, t=2.01, df=92, p<0.05; alphabet component: 4.0 seconds, 99% CI=–0.9 to 8.1, t=2.57, df=92, p<0.02 [unadjusted]; t=1.95, df=92, p<0.06 [adjusted]). Healthy sisters did not differ from healthy unrelated women on any of the general cognitive tasks.

On the set-shifting tasks, sisters with no eating disorders took significantly longer than healthy unrelated women on the shift component of the CatBat task, equating to a mean difference of 9.2 seconds (99% CI=1.5 to 17.0) (t=3.14, df=92, p=0.002), and had a higher ratio of Cat time to Bat time of 0.40 (99% CI=0.06 to 0.74) (t=3.12, df=92, p=0.002). A similar but nonsignificant effect was observed when women with anorexia nervosa were compared with healthy unrelated women for Cat time (estimated difference=8.4 seconds, 99% CI=–0.9 to 17.8) (t=2.37, df=92, p=0.02) and the CatBat ratio (increase of 0.36, 99% CI=0.04 to 0.68) (t=2.96, df=92, p=0.004). The women with anorexia nervosa and their unaffected sisters took significantly longer than healthy unrelated women to adjust to the change in ball size in the Haptic Illusion task, with differences of 7.1 illusions (99% CI=3.0 to 11.4) (t=4.48, df=92, p<0.001) and 6.5 illusions (99% CI=1.7 to 11.3) (t=3.54, df=92, p=0.001), respectively, from the healthy unrelated women. After adjustment for depression and obsessive-compulsive symptoms, this group difference remained significant in unaffected sisters (t=3.52, df=92, p=0.001) but fell below the significance level in the women with anorexia nervosa (t=1.78, df=92, p<0.08).

The performance of affected and unaffected sisters did not differ significantly on any set-shifting task. There were no differences in error rate between groups on the Trail Making tasks (data not shown but available on request). A comparison of individuals with anorexia nervosa who were or were not receiving current psychoactive medication revealed no significant group differences across all neuropsychology tasks (p>0.2).

In a subsidiary analysis to address the influence of illness state on performance in the women with anorexia nervosa, fully recovered women (N=23) were compared with those who were acutely ill and those who had recently recovered normal weight (N=24). The recovered group made significantly fewer errors than the acutely ill on the alphabet component of the Trail Making task (p=0.003, Mann-Whitney U test). Four (17%) of the fully recovered women made one or more errors on the alphabet, compared with 15 (63%) of those with acute anorexia nervosa. Error rates on these tasks were not correlated with anxiety or depression scores on the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale or scores on the Maudsley Obsessive Compulsive Inventory; therefore, there was no need for adjustment. Recovered women did not differ significantly from those with acute anorexia nervosa on any of the other neuropsychological tasks (all p>0.1).

A secondary analysis excluding the three women who had recently achieved normal weight from the acute group produced similar, nonsignificant findings (all p values p>0.1). Furthermore, within the anorexia nervosa group, body mass index did not correlate significantly with performance on any neuropsychological task (all Pearson correlation coefficients were below 0.20 in absolute value).

Discussion

This study set out to examine the possibility that set-shifting difficulties, thought to be trait markers for anorexia nervosa, could be classified as endophenotypes on the basis of findings in first-degree relatives. We found that the set-shifting difficulties evident in women with anorexia nervosa were shared by their healthy sisters. The most striking results were apparent from the CatBat cognitive set-shifting task and the Haptic Illusion task, which assess perceptual rigidity. Both affected and unaffected sisters took significantly longer to shift set on these tasks. There was also evidence of slowed alternation on the test for dysdiadochokinesis in women with anorexia nervosa and their unaffected sisters. None of these tests differed between women with acute anorexia nervosa and those who had fully recovered, suggesting that they are trait and not state effects. However, slower performance on some general cognitive tasks was specific to the anorexia nervosa group. The women with anorexia nervosa were slower than their healthy sisters and healthy unrelated subjects to complete nonshift components of the Trail Making task. The women who were fully recovered from anorexia nervosa were equally slow to complete these components, although they made significantly fewer errors on one of the tasks, suggestive of a different cognitive style.

This is the first study, to our knowledge, to investigate neuropsychological functioning in the unaffected siblings of individuals with an eating disorder. The finding that women with anorexia nervosa and their unaffected sisters exhibit similar difficulties in some set-shifting tasks has several implications. It suggests that reduced cognitive and perceptual flexibility may constitute a familial trait associated with a greater risk of developing anorexia nervosa rather than a consequence or scar of the illness. One possibility is that mental rigidity is linked to persistent abnormalities in the serotonergic system seen in anorexia nervosa, including elevated serotonin 5-HT metabolites in CSF and alteration in 5-HT

2A receptor binding

(20,

21). The serotonergic system has been strongly implicated in the regulation of impulsivity and cognitive inflexibility

(22–

25).

The results of this study are in agreement with the hypothesis that the pattern of neuropsychological functioning observed in previous studies may constitute a biological marker or heritable endophenotype in anorexia nervosa; unaffected sisters carry copies of illness susceptibility genes that are nonpenetrant for illness but manifest as the endophenotype. Indeed, it is now well accepted that human prefrontal function, which includes factors such as information processing speed and specific cognitive abilities, is under substantial genetic control

(26).

Evidence of shared neuropsychological traits in unaffected relatives parallels the results of studies in other complex disorders, such as schizophrenia

(27–

29), where illness-associated neuropsychological traits are evident in unaffected first-degree relatives when compared with unrelated subjects. A perhaps surprising finding is that unaffected sisters in this study had scores very similar to those of their affected sisters on the tasks of interest. One would expect the sisters’ scores to be intermediate because, on average, 50% of genes are shared. However, other studies of cognitive functioning in discordant siblings (e.g., for schizophrenia) have also reported similar impairments in both affected and unaffected siblings relative to unrelated comparison subjects

(29).

The set-shifting difficulties evident in this group of women with anorexia nervosa are largely consistent with previous reports from our group

(2–

4). Slowness on the dysdiadochokinesis test in anorexia nervosa, which did not reach statistical significance in our study, has also been reported by a different group

(30,

31). Our previous study using the same test battery

(3) found no effects of SSRI medication use on neuropsychological performance.

It is possible that the tasks included in our “set-shifting” battery are testing different aspects of information processing. The Haptic Illusion and CatBat tasks have an element of learning, i.e., they involve a period of training to establish the set (presentation of unequal-sized balls 15 times) or a narrative set where the letter c for cat is required (six times). When the set is changed, previous learning has to be extinguished and a new pattern put in place. Thus, these tasks may be measuring a failing in the process of extinction in individuals with anorexia nervosa. Strober

(32) has developed a theory about the maintenance of anorexia nervosa in which he suggests that “genetically driven variations in mechanisms underlying fear conditioning are posited as the second-stage contributor to the morbid level of fear that quickly ensues, and its prolonged resistance to extinction.” Both the abnormalities detected and the evidence of trait effects are compatible with this theory, although they suggest that the failure to extinguish learned responses may not be limited to fear conditioning. This line of thought merits further investigation.

In contrast to the finding in the current study, in an earlier study

(3) our group found that subjects with anorexia nervosa demonstrated difficulties on the Brixton Test and the Trail Making shift tasks. It is possible that these tasks are more sensitive to aspects of illness state than the CatBat and Haptic Illusion tasks. The women with anorexia nervosa in the current study had a higher current body mass index and a shorter illness duration than subjects with anorexia nervosa in our earlier study. Moreover, 37%, compared with 69% in the earlier study, were inpatients at the time of testing. Thus, the failure in replication could be ascribed to the differences in clinical state.

In common with our previous findings

(3), the women with anorexia nervosa in the current study took significantly longer to complete the two nonshift components of the Trail Making task. Comparable response times between acute and recovered subjects suggest that longer response time on these tasks is not a function of acute state. However, the absence of this feature in the healthy sisters suggests that this is either an individual-specific trait or a residual scar effect of having had anorexia nervosa.

An intriguing finding was that recovered subjects made significantly fewer errors than all other groups on the Trail Making alphabet task. Combined with the greater response times in the anorexia nervosa group relative to comparison subjects, across several tasks, this may indicate a pattern of responding in the recovered state that is consistent with a more cautious cognitive style. This finding is in keeping with the slow, accurate response style reported previously in anorexia nervosa

(33). The links between neuropsychological performance and aspects of personality in anorexia nervosa such as persistence and perfectionism, especially regarding concern over mistakes

(34), would be an interesting avenue for future research.

The strengths of this study include the use of a discordant sibling-pair design, which is a powerful tool in investigating the extent to which illness-associated characteristics are unique or shared within families

(35). Eating disorder diagnoses were based on a semistructured interview that uses a timeline approach to elicit lifetime eating disorder symptoms, circumventing some of the reliability questions raised by self-reported, questionnaire-based diagnoses. The neuropsychological battery used in this study was specifically selected to test the hypothesis that individuals with anorexia nervosa might have difficulty in set-shifting and was identical to that used in a number of previous studies, allowing comparisons to be made. We were able to consider the influence of depression, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive symptoms, and medication use in our analysis, all of which may be considered potential confounders when assessing neuropsychological performance.

This study has some limitations. Because women with anorexia nervosa were recruited at different stages of recovery and treatment for this study, we could not control for the effects of current nutritional state on neuropsychological performance. In addition, we cannot determine from these data whether the pattern of set-shifting difficulties reported in women with anorexia nervosa and their healthy sisters is specific to this disorder or is a feature of other axis I disorders. The finding that anxiety, depression, and obsessive-compulsive symptoms had minimal effects on performance, however, suggests some degree of specificity. This test battery has not been used in individuals with primary depression, anxiety, or obsessional disorders in the absence of an eating disorder; therefore, the use of this battery in these groups would represent a valuable future extension of the current research.

To conclude, this study provides further support for the possibility that information processing (set-shifting or extinction) difficulties may be part of the endophenotype in anorexia nervosa. To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate such traits in the relatives of individuals with anorexia nervosa. The extent to which altered performance on the neuropsychological battery reflects a susceptibility to anorexia nervosa or correlates of certain personality traits is an interesting question that merits further exploration. Future studies assessing the heritability and exact form of these traits would be required to accept or refute the endophenotype theory.