Homelessness remains a persistent public mental health concern. Between one-fourth and one-third of homeless persons have a serious mental illness such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or major depression

(2–

4). Homelessness exacts a heavy toll, including low quality of life

(5), risk of assault

(6), and early death

(7). Although the rates of mental and physical illnesses are high among homeless persons

(8,

9), their access to health services is more difficult

(10,

11). They often do not have a regular source of health care

(12), and the daily struggle for food and shelter may take priority over mental health care

(12). As rents in large cities increase, the number of homeless persons can be expected to rise

(13).

Public mental health systems have been called on to better meet the needs of homeless persons with mental illness

(14,

15), yet few prior investigations have examined homelessness among patients with serious mental illness in large public mental health systems. Prior studies have sampled hospitalized patients

(16–

20) or homeless persons

(9,

21,

22). A study of veterans hospitalized in the psychiatric wards of Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) facilities found that 18% were literally homeless at the time of admission

(23). In persons first hospitalized for a psychotic disorder, 15% had an episode of homelessness

(16). We are aware of only one published investigation of all patients in a public mental health system; in that study, 7.5% of the patients treated for a psychotic disorder used a public shelter during a 3-year period

(24).

Previous investigations have found a higher risk of homelessness in men

(24,

25), compared with women, and in African Americans

(17,

19), compared with other ethnic groups. Similarly, substance abuse has been associated with homelessness

(8,

9,

26). Homeless persons with serious mental illness have been reported to have higher levels of psychiatric hospital use

(14,

21,

27) and higher mental health treatment costs

(20) than not-homeless patients. Veterans who were homeless at the time of psychiatric hospitalization had mental health care costs that were 18% higher than not-homeless veterans

(20). In addition, prior studies have found that homeless persons with serious mental illness are more likely to receive mental health treatment in hospitals than in outpatient clinics

(21,

27).

To our knowledge, no published report has compared the prevalence of, risk factors for, and use of mental health services among homeless and not-homeless persons treated for serious mental illnesses in a large public mental health system. In the present study, we used data from San Diego County’s Adult Mental Health Services to evaluate the prevalence of homelessness, factors associated with homelessness, and effect of homelessness on mental health service utilization among patients treated for serious mental illness in county mental health services. We sought to test the following hypotheses: 1) Homelessness would be associated with younger age, male gender, minority ethnic group status, substance use disorder, lack of Medi-Cal (Medicaid in California) insurance, diagnosis of schizophrenia, and lower levels of functioning; and 2) homeless persons with serious mental illness would use more emergency-type and less outpatient-type mental health treatment, compared to not-homeless patients. We employed multivariate regression analyses to control for potentially confounding variables. We hoped to provide information that could be used by public policy makers and administrators of public mental health systems as they design, implement, and evaluate interventions to reduce or prevent homelessness among persons with serious mental illness treated in public mental health systems.

Method

San Diego County is the sixth largest county in the United States and has a diverse ethnic composition. It is located on the United States-Mexico border, and the largest ethnic minority group is Latinos, who make up 23% of the adult population. Caucasians constitute 60% of adults, and African Americans and Asians each account for 5% of adults

(28). The San Diego Regional Task Force on Homelessness estimates that there are 15,000 homeless persons in San Diego on any given night, but only 4,200 shelter beds. Although the physical environment for homeless persons in San Diego is probably more benign in the winter, compared to colder areas of the country, it is fairly similar to that in other large sunbelt cities in the southern and southwestern United States, in which increasingly greater portions of the homeless persons in the United States live. A prior investigation of homeless individuals in San Diego found that 80% of the homeless people with mental illness had lived in San Diego for more than 5 years, with little seasonal migration in this group

(29). Similar to other American cities, San Diego has an array of homeless shelters operated by religion-based and nonprofit groups

(30).

The data used for this study were extracted from the county’s Adult Mental Health Services database, which included demographic information (age, gender, ethnicity, and presence of Medi-Cal coverage) and clinical information, including psychiatric diagnosis, presence of substance use disorders, and Global Assessment of Functioning Scale (GAF) score. We used data from fiscal year 1999–2000, the latest year for which complete data were available.

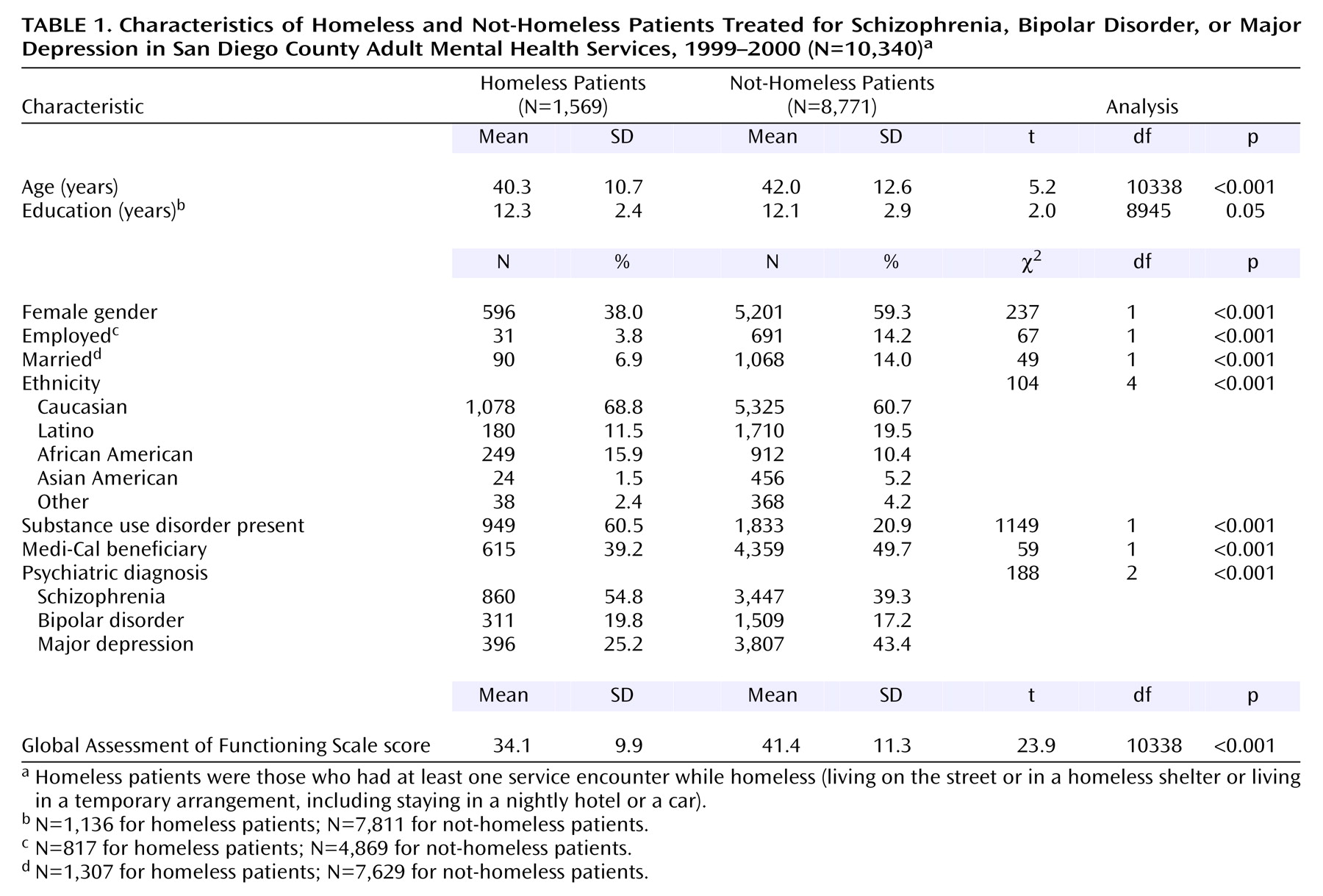

We included adults with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or major depression who received treatment at least once during the year and had data recorded for ethnicity, living situation, and GAF score. We excluded persons in jails or in locked psychiatric facilities. Substance use disorder was categorized as present if any substance use diagnosis was assigned during the year. We used the average of the intake GAF scores across all Adult Mental Health Services encounters as a measure of patient functioning. There were 15,159 persons with at least one encounter and a diagnosis of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or major depression seen in Adult Mental Health Services during 1999–2000. From this sample we excluded 641 patients with no data on race or ethnicity and 2,226 patients with no recorded GAF score. The treating clinician recorded data on living situation at admission, and we defined each person’s living situation as the one that was most frequently reported (modal living situation) during the various contacts with Adult Mental Health Services during the year. We excluded 1,952 patients whose modal living situation was a “justice-related facility” (i.e., jail), locked psychiatric hospital, or drug or alcohol abuse facility. The final study sample included 10,340 patients. Compared with the patients included in the final sample, the patients who were excluded were younger (mean age: 41.7 years versus 42.3 years) (p<0.001, t test), more likely to be male (53.1% versus 44.1%) (p<0.001, chi-square test), and more likely to have a diagnosis of schizophrenia (48.6% versus 41.7%) (p<0.001, chi-square test) but less likely to have a diagnosis of major depression (33.7% versus 40.7%) (p<0.001, chi-square test). (Although these differences were statistically significant, they may not be of clinical significance.)

We dichotomized the study sample into patients who were homeless versus those with no recorded encounter while homeless. The two subcategories of homelessness in the Adult Mental Health Services system were: 1) homeless no-residence (living on the street or in a homeless shelter) and 2) homeless-in-transit/temporary arrangement (homeless people who were new to San Diego or in a temporary arrangement, including staying in a nightly hotel or a car). We conducted all reported analyses with homelessness defined as having at least one recorded encounter while homeless (N=1,569). We also repeated the analyses using two narrower definitions of homelessness: 1) using data only for patients in the “homeless no-residence” category (N=1,309), thereby excluding patients in “homeless-in-transit/temporary arrangement” living situations, and 2) using data only for patients with at least two recorded encounters while homeless (N=1,010).

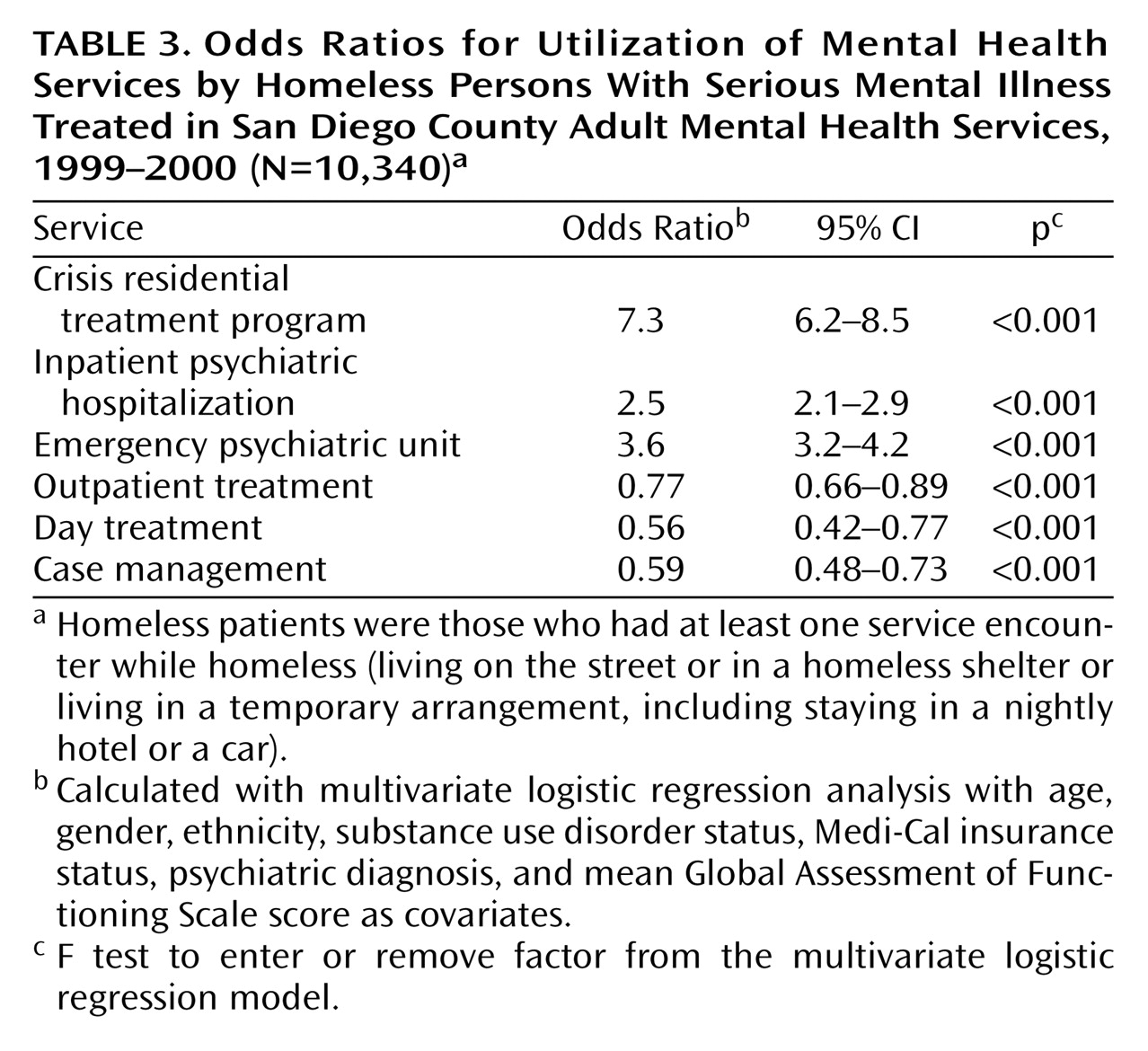

Mental health services were consolidated into six service categories: 1) crisis residential treatment programs, 2) inpatient psychiatric hospitalization, 3) emergency psychiatric unit (the single county-operated psychiatric emergency department), 4) outpatient treatment, including both medication and psychotherapy, 5) day treatment (rehabilitation, day treatment, or partial hospitalization programs), and 6) case management services billed under a case management procedure code.

Statistical Analysis

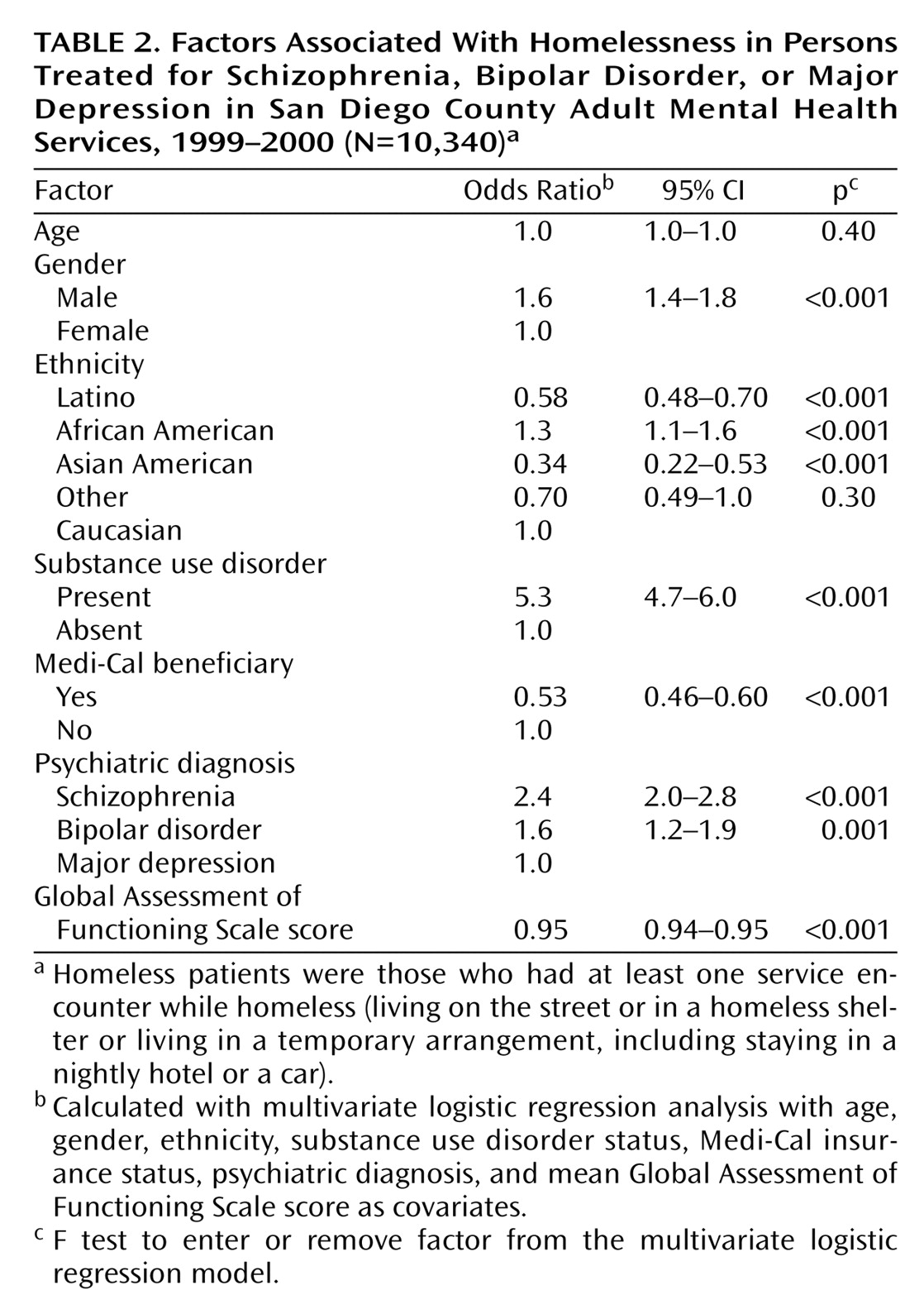

The homeless and not-homeless patients were initially compared on demographic and clinical characteristics by using t tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. All the tests were two-tailed, and the alpha value was set at p<0.005 to correct for multiple comparisons. Factors associated with homelessness were examined with multivariate logistic regression analysis. The following variables were included in the latter analysis (with the respective reference groups listed in parentheses): age, gender (female), ethnicity (Caucasian), substance use disorder (none), Medi-Cal insurance (nonbeneficiaries), psychiatric diagnosis (major depression), and mean GAF score. We excluded from the analyses education, employment status, and marital status because of the sizable number of subjects with missing data for these variables.

The odds ratios for utilization of each of the six mental health services were calculated by using multivariate logistic regression analysis. Each patient was classified as having utilized a particular service if he or she had at least one recorded encounter in that service during the fiscal year. These analyses included living situation (homeless versus not homeless), age, gender, ethnicity, substance use disorder status, Medi-Cal status, psychiatric diagnosis, and mean GAF score as covariates. The variables were entered into the models in a single step, and the odds ratios were computed by using BMDP statistical software (Berkeley, University of California). Odds ratios were considered statistically significant when the p value was <0.005, to correct for multiple comparisons.

Discussion

In this study of patients treated for serious mental illness in a large public mental health system, 15% were homeless at the time of at least one service encounter in a 12-month period. Male gender, African American ethnicity, presence of substance use disorder, and a lack of Medicaid insurance were associated with homelessness. Conversely, Latino and Asian American ethnicities were associated with lower rates of homelessness. Patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder had higher rates of homelessness, compared to those with depression, as did patients with lower GAF scores. Compared with their housed counterparts, homeless patients were more likely to use emergency-type services, including inpatient services, crisis residential services, and the emergency psychiatric unit, and less likely to receive outpatient-type services.

Our finding that 15% of the patients treated for serious mental illness were homeless during a 1-year period indicates a higher prevalence of homelessness than that reported in the only other published study that examined homelessness among all persons treated in a public mental health system

(24). That study found that 10% of the patients treated for schizophrenia and 7% of those treated for affective disorders used a public shelter during a 3-year period, compared to 2.8% of the general population. Other investigations of hospitalized patients have reported that 20% of veterans were homeless at the time of admission to a VA psychiatric ward

(20) and that 15% of persons with psychotic disorders hospitalized for the first time were homeless

(16). Clearly, homelessness affects a sizable portion of persons with serious mental illness, and persons with serious mental illness are at greater risk for homelessness than the general population.

Patients with schizophrenia were 2.4 times more likely, and those with bipolar disorder 1.6 times more likely to be homeless than those with major depression. A prior study found that 9.7% of patients with schizophrenia used a public shelter, compared with 6.7% of patients with affective psychosis

(24), while a second investigation did not find a significant difference in rates of homelessness among patients with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder with psychosis, or depression with psychosis

(16). These two previous studies did not control for other clinical and demographic variables associated with homelessness. Our findings, in light of these prior investigations, suggest that specific psychiatric diagnoses confer different levels of risk for homelessness.

For the demographic and clinical factors associated with homelessness, there were several notable findings. Unlike earlier researchers, we found no association between age and homelessness

(9). A higher rate of homelessness in men versus women was previously reported

(31) and may be in part related to the presence of additional resources and support available to families that are homeless or at risk of homelessness, which are primarily headed by women. We found that African Americans had a higher risk of homelessness, and Latinos and Asians a lower risk of homelessness, compared to Caucasians. We are aware of only one prior report examining homelessness in Latinos with serious mental illness

(19), which also reported a lower rate. In San Diego County, African Americans constitute 5% of the general population, 11% of the Adult Mental Health Services population with serious mental illness, and 16% of the homeless patients with serious mental illness treated in Adult Mental Health Services. Latinos contribute 23% of the general population, 19% of the Adult Mental Health Services patients, and 12% of the homeless patients. It is possible that the higher rate of homelessness among African Americans may be due in part to fewer community resources for this group of patients, whereas the larger Latino community may be able to provide more resources to protect against homelessness. However, African Americans have been found to be at higher risk of homelessness in other cities with larger African American populations such as New York and Philadelphia

(17,

19,

24). An investigation of homeless persons in Los Angeles, only some of whom had mental illness, found lower rates of homelessness in Caucasians and Latinos than in African Americans. However, the African Americans and Latinos reported higher rates of childhood poverty, whereas the Caucasians reported higher rates of family dysfunction

(32). Factors other than minority ethnic status, such as family structure and social support, may be relevant to homelessness, and further work is needed to better understand this relationship.

As in previous investigations, substance use disorders were associated with homelessness

(8,

9,

26). Treatment of substance abuse has been reported to improve outcomes in homeless persons with dual diagnoses of serious mental illness and substance abuse

(33); however, access to substance abuse treatment is more difficult for homeless persons with serious mental illness than for other homeless persons

(34). Similarly, patients who did not have Medi-Cal insurance were twice as likely to be homeless as patients with Medi-Cal. Homeless persons with psychotic disorders have been reported to have greater difficulty obtaining and maintaining entitlement benefits, compared with homeless persons without psychotic disorders

(35).

Homelessness was associated with increased emergency-type and decreased outpatient-type mental health treatment. Several studies have reported higher rates of psychiatric hospital use among homeless persons with serious mental illness

(14,

21,

27), and higher costs for mental health treatment for homeless versus not-homeless veterans have been reported

(20). However, these prior investigations were limited to samples of homeless persons

(14,

21,

27) or to hospitalized veterans

(20). In this study of all patients treated in a large public mental health system, homeless patients were more than twice as likely to be hospitalized as were not-homeless patients. In our prior investigation of Medi-Cal recipients treated in San Diego County Adult Mental Health Services, inpatient costs constituted the largest portion of mental health costs for those patients who were hospitalized

(36). Studies of interventions targeting homeless persons with mental illness have reported fewer inpatient hospitalizations and fewer days homeless in those who received the interventions

(25,

37–41). In some of these interventions, the total costs were lower for the intervention group

(37,

38), whereas in other reports the improved patient outcomes required greater expenditures

(41). Improved care for homeless persons with serious mental illness may be cost-effective or at least may result in improved patient outcomes with only moderate increases in total costs.

Unlike some prior investigations that evaluated the prevalence of mental illness among homeless persons

(8,

9,

11), the current study examined homelessness among patients treated for serious mental illness in the public mental health system. An important methodological aspect of our investigation was the definition of homelessness. Published definitions of homelessness have ranged from living on the street or in a homeless shelter

(8) and using a public homeless shelter at least once in 3 years

(24) to being homeless at the time of admission to a psychiatric unit

(20). Our definition of homelessness—i.e., at least one encounter of service utilization while homeless over a 1-year period—is well within this range of definitions. In addition, repeating our analyses with two more restrictive definitions of homelessness did not change our findings.

The strengths of our study include the use of a large sample from a public mental health care system, the comparison of patients with different types of serious mental illness, measurement of mental health service utilization over a 1-year period based on computerized records rather than on subjective recall, and adjustment for potentially confounding variables in the statistical analyses. There were also several limitations to this investigation. The source of the data was an administrative database, and the diagnoses were made by a number of clinicians and may not be as accurate as those made with diagnostic research instruments. Similarly, the level of accuracy of GAF scores recorded in administrative databases may not be as high as in clinical research studies

(42). Data for only 1 year were used, and we did not examine homelessness over time. Patients who received no psychiatric care in the county’s Adult Mental Health Services during the study period were not included. Data on living situations were based on patients’ self-reports. Medi-Cal beneficiaries likely also received other entitlement benefits (e.g., Supplemental Security Income) that were not recorded in the database but that may help explain the lower rates of homelessness among Medi-Cal beneficiaries. The Adult Mental Health Services database underrepresented the use of emergency department psychiatric treatment, as we included only treatment received in the agency’s emergency psychiatric unit. The mental health services we investigated did not include less traditional services specifically targeting homeless persons with mental illness; however, these services were not provided by the county’s Adult Mental Health Services during the time period of this report. Our data came from a single large public mental health system and may not generalize to smaller public mental health systems or to patients with less severe psychiatric disorders.

In conclusion, homelessness is a serious problem among patients with serious mental illness and is associated with two potentially modifiable factors—comorbid substance use disorders and a lack of Medicaid insurance. Although it would be naive to assume that treatment for substance use disorders and provision of Medicaid insurance could solve the problem of homelessness among persons with serious mental illness, further research is warranted to test the effect of interventions designed to treat patients with dual diagnoses and to assist homeless persons with serious mental illness in obtaining and maintaining entitlement benefits.

Homeless persons with serious mental illness represent one of the most vulnerable and disadvantaged segments of the society. The recent budget crises in many states, including California, may worsen the outlook for persons who are homeless and mentally ill. As the quote by the former Surgeon General given at the beginning of this article suggests, the quality of national health care may be measured by the care we provide to the most vulnerable among us. The mental and physical health care of homeless patients with serious mental illness should be one of the top societal priorities

(43). From a research perspective, systemwide studies of barriers to health care service use and ways to overcome them will be useful.