Biederman and colleagues

(8) studied 84 clinic-referred ADHD adults, 36 nonreferred ADHD adults, and 207 adults without ADHD. The ADHD groups demonstrated higher rates of oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, depression, substance abuse/dependence, and anxiety. Subsequent reports described a higher risk for psychoactive substance use disorders, particularly among men and subjects in lower socioeconomic classes

(9). The ADHD individuals had earlier onsets of substance use disorders than did the comparison subjects

(10,

11). Murphy and Barkley

(12), in a study of 172 clinically referred ADHD adults and 30 comparison subjects, noted higher rates of alcohol abuse or dependence (35% versus 10%), drug abuse or dependence (14% versus 3%), oppositional defiant disorder (30% versus 7%), and conduct disorder (17% versus 0%) in the patients with ADHD. The ADHD group also exhibited high rates of comorbid anxiety disorders (32%), major depressive disorder (18%), and dysthymia (32%), although these were not significantly higher than the rates for the comparison subjects.

While existing evidence suggests that there is a significant risk of lifetime psychiatric comorbidity in adult ADHD, the design features of previously reported studies limit the generalizability of the findings. Studies based on DSM-III-R criteria might underrecognize comorbidity with the predominately inattentive subtype. Older studies of hyperactive children emphasized male subjects and might not represent clinical phenomenology in female subjects. In comparisons of comorbidity across ADHD subtypes, classification has been based on adult presentations, which do not reflect changes in symptom pattern over time. Finally, most published studies have been based on clinical study groups, which might bias the reported rates of psychopathology.

The UCLA ADHD Genetic Study examined adult ADHD and comorbid psychopathology in a large, nonclinical study group. Families were recruited on the basis of having two or more affected siblings with ADHD. Parents of these affected sibling pairs underwent comprehensive assessment to identify lifetime psychopathology and ADHD versus non-ADHD status. We explored several specific hypotheses, namely, 1) that findings in ADHD adults identified through multiplex families would be similar to those for clinical groups described in the literature, specifically, that subjects with ADHD would have higher rates of psychiatric comorbidity; 2) that ADHD subjects would evidence earlier ages at onset for comorbid conditions; 3) that differences in comorbidity would occur across ADHD subtypes; and 4) that other, non-ADHD factors would contribute additional risk for psychopathology.

Results

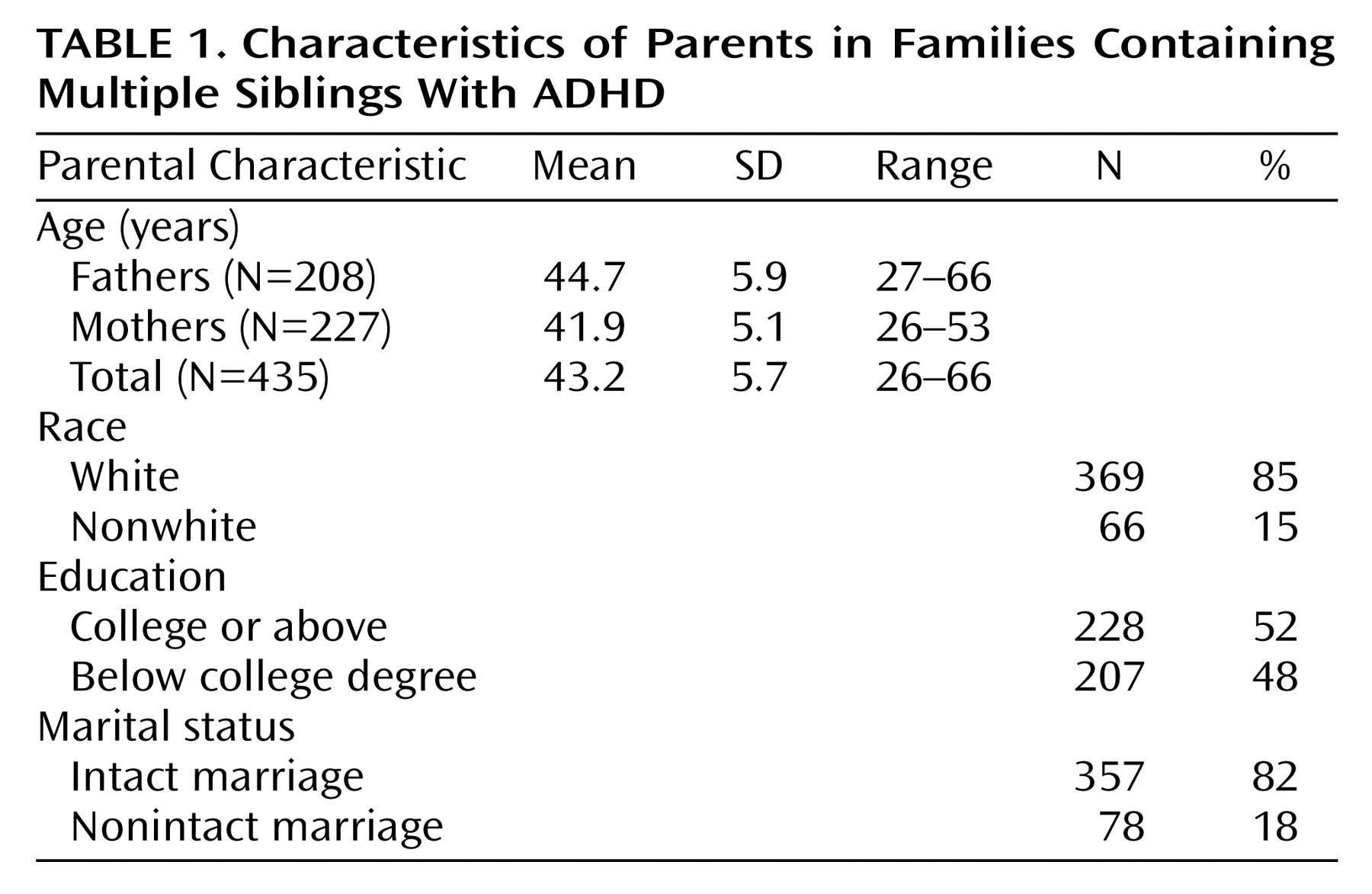

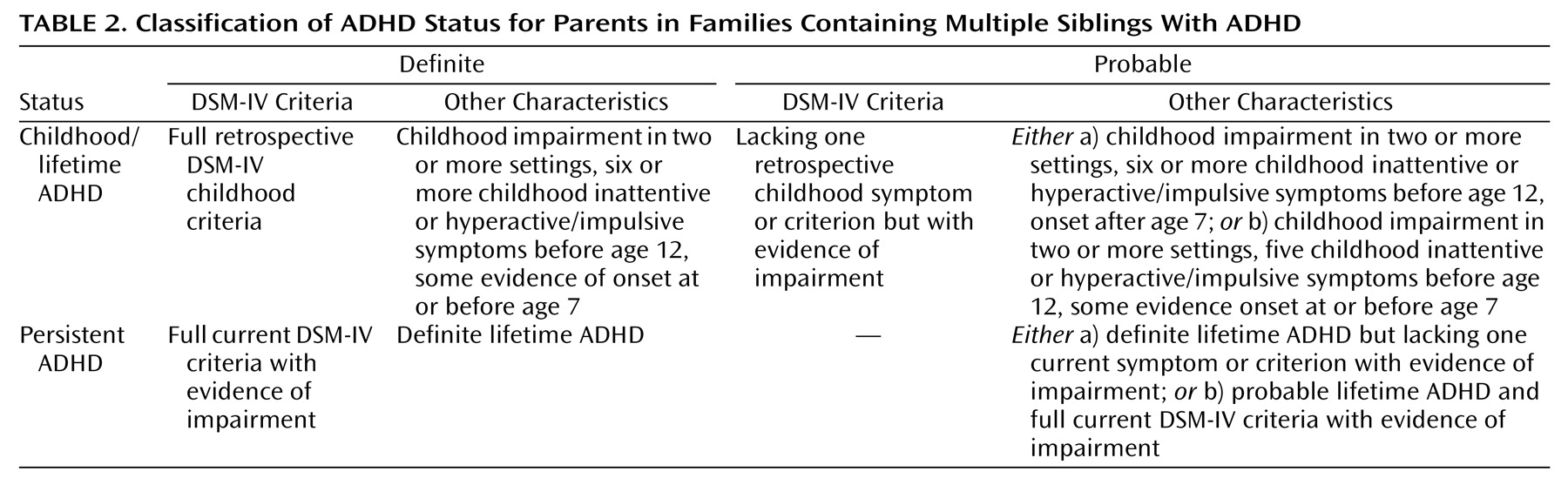

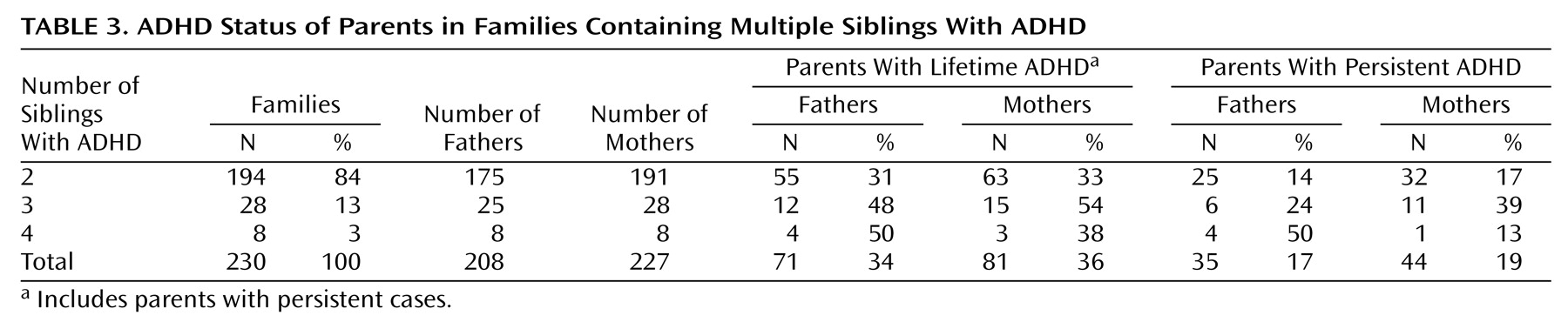

Family and parental ADHD status is summarized in

Table 3. The modal numbers of childhood inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive symptoms endorsed by ADHD parents were eight and six, respectively, compared with zero and zero in non-ADHD parents. The lifetime ADHD group comprised 35% of the subjects (N=152). Of the parents with lifetime ADHD, 53% (N=81) had the inattentive subtype and 47% (N=71) had the hyperactive/impulsive subtype or combined subtype, and there was no difference by sex (χ

2=1.8, df=1, p=0.17). The remaining 65% of the subjects (N=283) were unaffected.

Of the 230 families, 100 (43%) had no parent with ADHD, 108 (47%) had one affected parent, and 22 (10%) had two affected parents; these rates are not different from those expected under random mating (χ

2=0.9, df=1, p=0.33). ADHD parents were more likely to be Caucasian (χ

2=6.4, df=1, p=0.01), unskilled workers (χ

2=16.6, df=7, p=0.02), and without a college degree (χ

2=5.5, df=1, p=0.02). There were no group differences by sex (χ

2=0.1, df=1, p=0.73) or marital status (χ

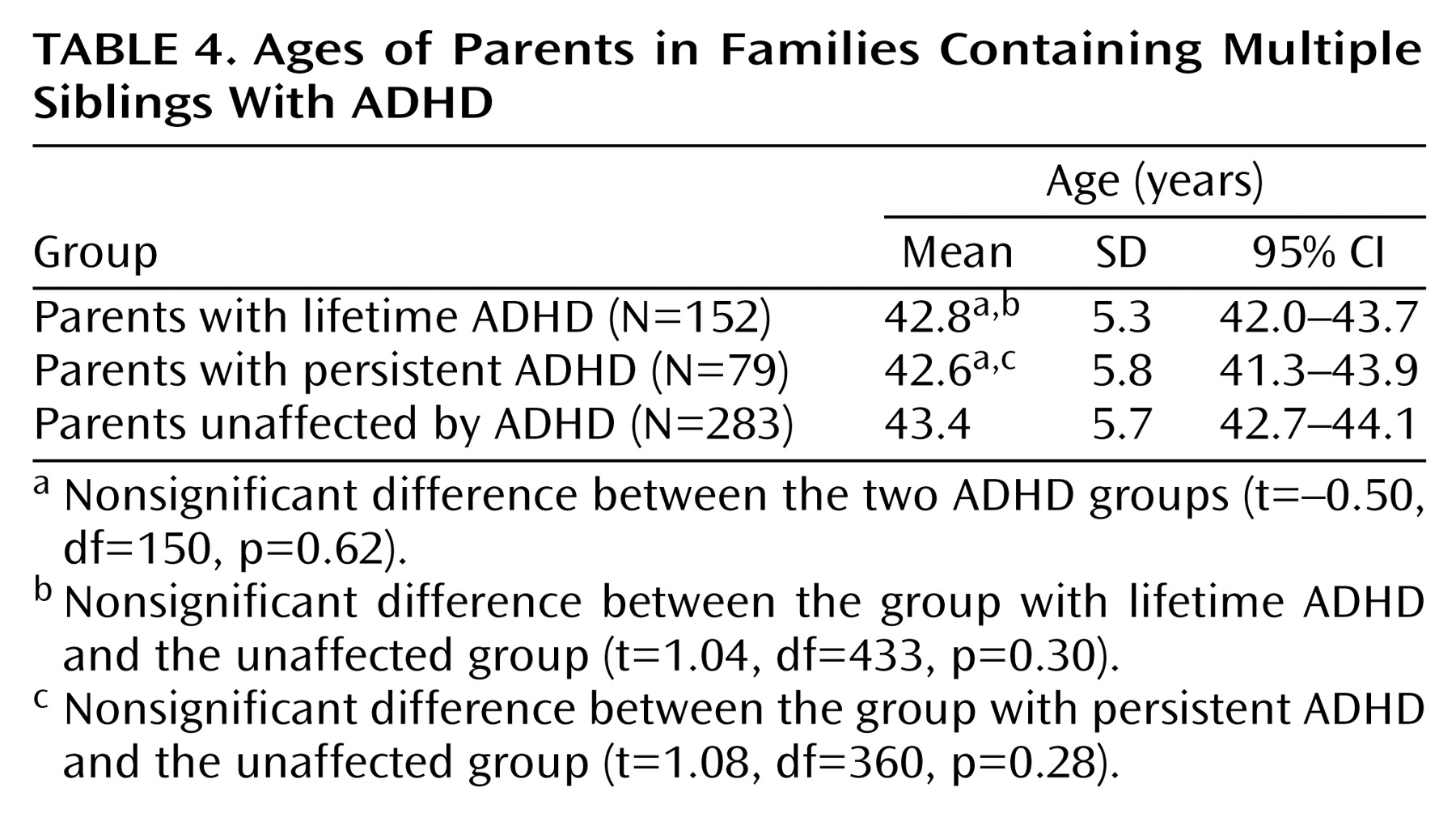

2=1.6, df=2, p=0.20). There were no significant differences in mean age between the groups with lifetime, persistent, and no ADHD (

Table 4).

The ADHD parents had more lifetime psychopathology, with 87% having at least one and 56% at least two other psychiatric disorders, compared with 64% and 27%, respectively, in the non-ADHD subjects (χ

2=63.3, df=5, p<0.0001).

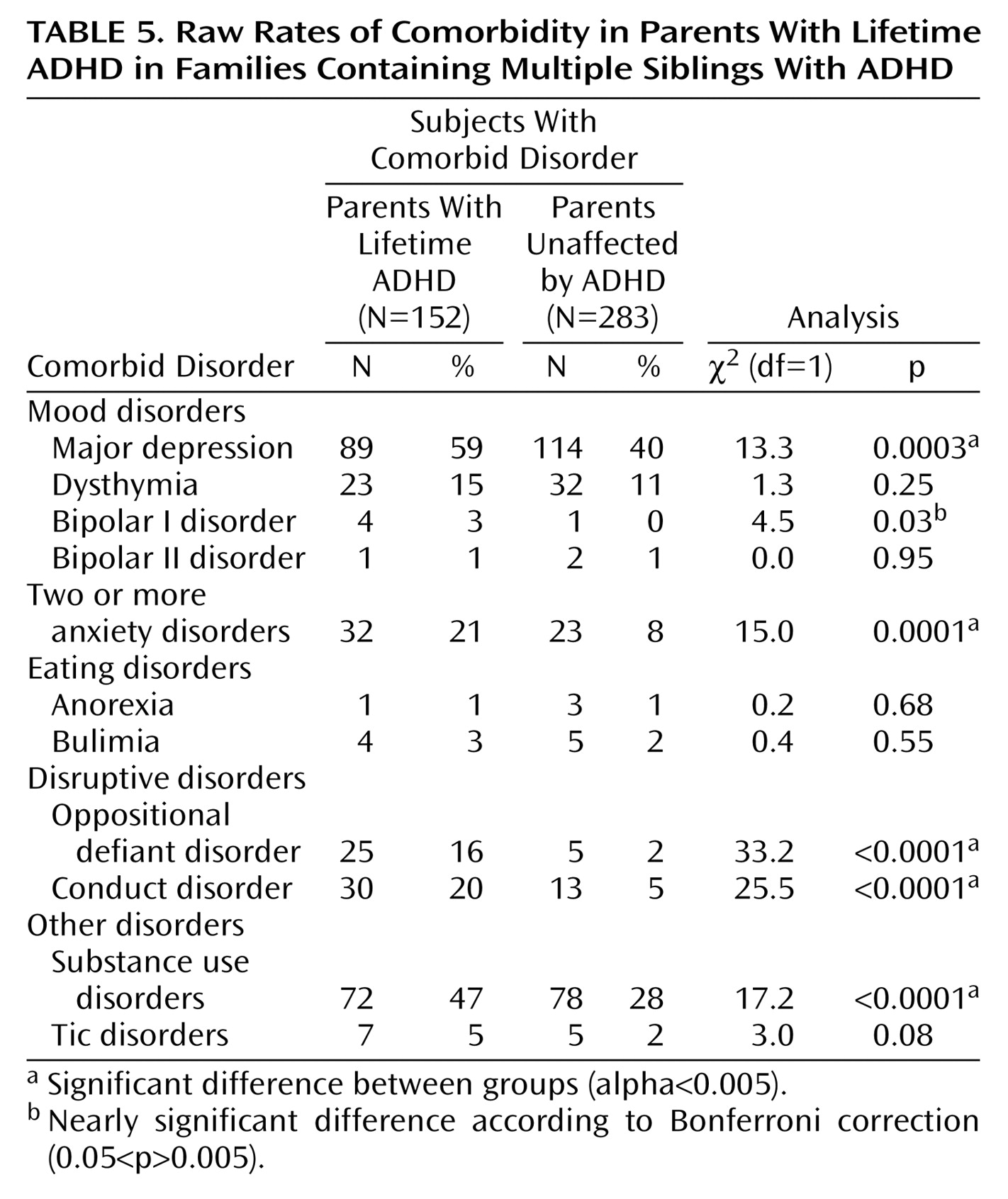

Table 5 compares the raw frequencies of comorbid psychiatric conditions in the parents with lifetime ADHD and those without ADHD. Given that single anxiety disorders are common, we examined a threshold of two or more anxiety disorders to minimize overdiagnosis, as suggested by others

(8). Anxiety disorders included separation anxiety disorder, panic disorder, social phobia, simple phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, and PTSD. Substance abuse and substance dependence were considered together as substance use disorders. The subjects with lifetime ADHD showed significantly higher rates of major depressive disorder, multiple anxiety disorders, oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, and substance use disorders. A nonsignificantly higher rate of bipolar I disorder was detected, but the analysis was limited by the relatively low number of bipolar subjects.

The numbers of subjects were sufficient to compare the mean ages at onset for five comorbid conditions. The ADHD subjects had earlier onsets of oppositional defiant disorder (mean age=7.6 years, SD=3.0) than did the subjects without ADHD (mean=10.6 years, SD=3.0) (t=3.12, df=45, p=0.003) and major depressive disorder (mean age=24.7 years, SD=10.4, versus mean=29.0, SD=9.9) (t=2.82, df=194, p=0.005). Nearly significant differences in onset age were noted for dysthymia (mean=21.5 years, SD=10.7, versus mean=29.8 years, SD=13.2) (t=2.43, df=51, p=0.02) and conduct disorder (mean age=10.2, SD=3.0, versus mean=12.2, SD=2.3) (t=2.22, df=38, p=0.03). There was no difference in age at onset for substance use disorders between the parents with lifetime ADHD (mean=18.3 years, SD=5.0) and the parents without ADHD (mean=18.4, SD=6.1) (t=0.06, df=86, p=0.95).

Assessment of comorbidity across subtypes of lifetime ADHD revealed a higher rate of oppositional defiant disorder in the group with hyperactive/impulsive or combined symptoms (25%) than in the group with the inattentive subtype (9%) (χ2=7.7, df=1, p=0.006). No other differences were evident.

Persistent ADHD was diagnosed in 79 (52%) of the 152 subjects with lifetime ADHD. Their patterns of comorbidity were similar to those in the group with lifetime ADHD, and the rates of comorbid disorders were significantly higher than the rates for non-ADHD parents. Among the subjects with persistent cases, 63% evidenced major depressive disorder (χ2=13.2, df=1, p=0.0003), 25% had multiple anxiety disorders (χ2=17.4, df=1, p<0.0001), 18% had oppositional defiant disorder (χ2=31.6, df=1, p<0.0001), 18% had conduct disorder (χ2=15.4, df=1, p<0.0001), and 47% had substance use disorders (χ2=10.6, df=1, p=0.001). Bipolar I disorder was significantly more common than in the unaffected subjects (p=0.009, Fisher’s exact test), despite a low overall frequency of bipolar disorder (four out of 79 parents with persistent ADHD and one of 283 non-ADHD parents). Subjects with the hyperactive/impulsive or combined subtype exhibited a higher rate of substance use disorders than those with the inattentive subtype (69% versus 34%) (χ2=9.0, df=1, p=0.003), and there were nonsignificantly higher rates of oppositional defiant disorder (31% versus 10%) (χ2=5.6, df=1, p=0.02) and conduct disorder (31% versus 10%) (χ2=5.6, df=1, p=0.02).

The group differences in the frequencies of comorbid disorders according to Kaplan-Meier age-corrected risks were consistent with those presented for the raw frequency distributions. The morbid risks for the parents with lifetime ADHD versus non-ADHD parents were 16.5% (SE=3.1%) versus 3.9% (SE=1.2%) for conduct disorder, 72.7% (SE=8.6%) versus 44.5% (SE=3.3%) for major depressive disorder, 17.5% (SE=3.2%) versus 8.3% (SE=1.9%) for multiple anxiety disorders, 56.6% (SE=8.1%) versus 32.9% (SE=4.2%) for substance use disorders, and 28.0% (SE=10.1%) versus 1.1% (SE=0.6%) for oppositional defiant disorder. A similar pattern was evident for the risks of the parents with persistent ADHD versus those of the non-ADHD subjects for conduct disorder (mean=13.4%, SE=3.9%, versus mean=3.9%, SE=1.2%), major depressive disorder (mean=78.2%, SE=7.8%, versus mean=44.5%, SE=3.3%), multiple anxiety disorders (mean=19.7%, SE=4.8%, versus mean=8.3%, SE=1.9%), substance use disorders (mean=44.9%, SE=5.7%, versus mean=32.9%, SE=4.2%), and oppositional defiant disorder (mean=30.9%, SE=12.7%, versus mean=1.1%, SE=0.6%). All differences in age-corrected rates were significant at p<0.005.

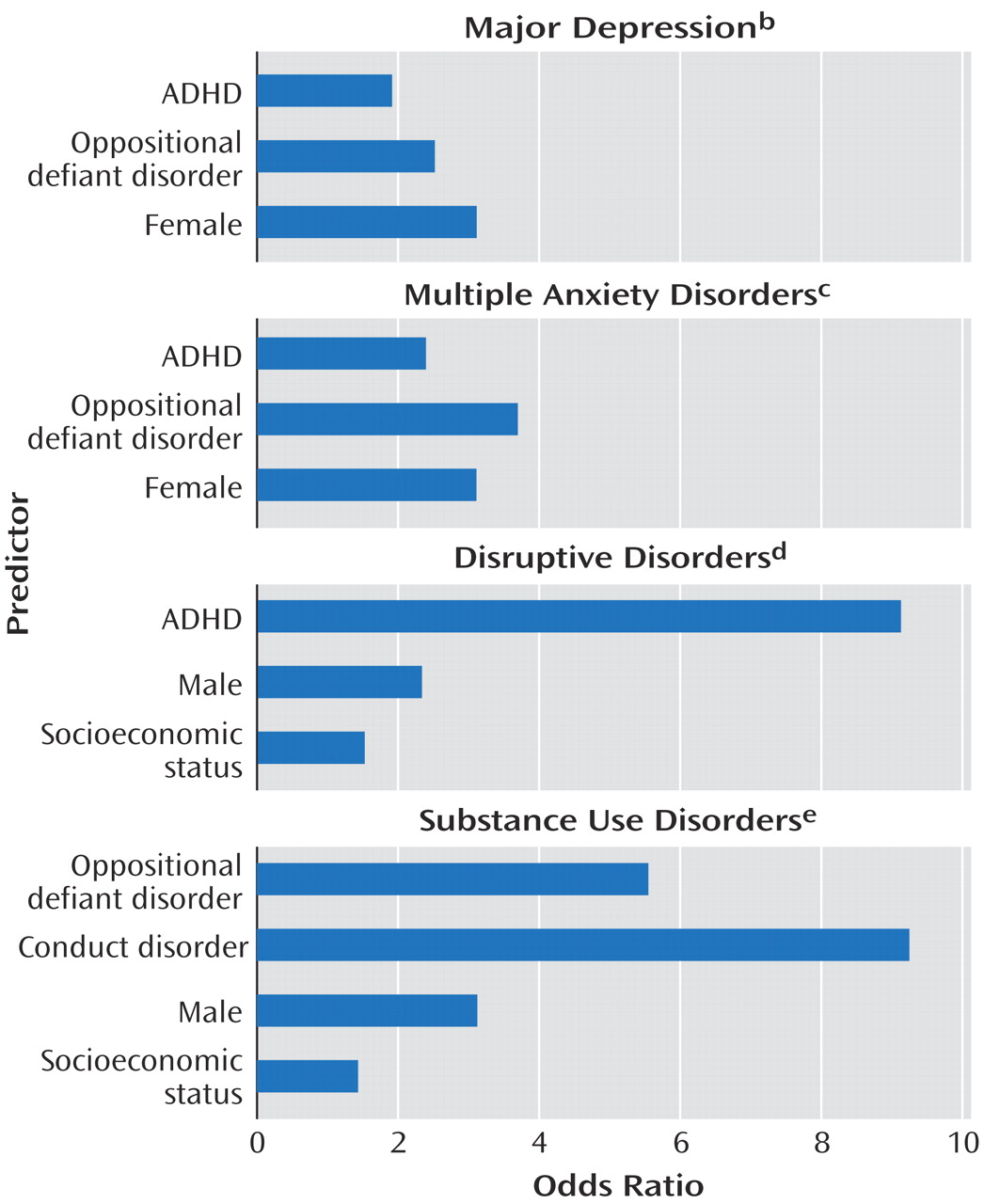

Odds ratios and goodness-of-fit tests from logistic regression models for four comorbid disorders associated with lifetime ADHD appear in

Figure 1. Disruptive disorders were strongly influenced by ADHD and male sex. For major depression, substance use disorders, and multiple anxiety disorders, oppositional defiant disorder invariably played a greater role than ADHD; conduct disorder played the largest role in substance use disorders. ADHD was not a significant risk factor for substance use disorders when male sex, disruptive behavior disorders, and socioeconomic status were controlled. Sex differences emerged, with women demonstrating greater risks for mood and anxiety disorders and men having a higher risk for substance use disorders, independent of ADHD status. Hosmer-Lemeshow chi-square tests indicated that the observed data were not significantly different from expected values derived from each model (p>0.05). Most models had good estimation of predicted variables (concordance>0.70).

Discussion

This study confirms and expands previous findings of greater risk for comorbid psychopathology in adult ADHD. Like others, we demonstrated lower educational and occupational achievement in adults with ADHD

(8,

12). Results from this current study are particularly noteworthy, given the large number of subjects, inclusion of an unaffected comparison group, and nonclinical ascertainment. The higher rates of comorbidity in adult ADHD do not appear to result from clinical referral bias or recruitment from tertiary care populations.

The patterns of comorbidity confirm findings in earlier studies, with high rates of lifetime depression, anxiety, disruptive behaviors, and substance use disorders. Higher risk for disruptive behavior disorders was predicted by ADHD and male sex, as noted by others

(13). Also consistent with other reports

(4,

5,

8,

13) was the fact that risk for substance use disorders was mediated by disruptive behavior disorders, male sex, and lower socioeconomic status, without an apparent direct effect from ADHD. The relationship between adult ADHD and internalizing disorders is less clear. The higher rate of major depressive disorder seen in the current study is consistent with some clinical findings

(8) but not others

(12). ADHD contributed significant risk for major depressive disorder but less than that conferred by female sex and oppositional defiant disorder. Similarly, although ADHD and multiple anxiety disorders were associated on univariate tests, female sex and oppositional defiant disorder conferred more risk than ADHD on logistic regression. The R

2 vales for each logistic regression model suggest that other unmeasured variables contribute substantial additional risk for each condition. Overall, the patterns of comorbidity in this subject group confirm that ADHD is a general risk factor for mood and anxiety disorders as well as disruptive behavior. The mechanisms by which lifetime ADHD increases risk for emotional disorders remains to be determined.

In this study we considered both lifetime and persistent ADHD status. Persistent ADHD is an arbitrary construct. Persistence is defined by symptom thresholds developed for children that have never been validated in adults. Some have noted that ADHD persistence is a matter of syndromal definition and not continued dysfunction

(22), while others have suggested that lower symptom thresholds more appropriately define groups of clinically impaired adults

(12,

23). Approximately 50% of our subjects with retrospectively determined childhood ADHD continued to evidence full persistence, a finding similar to that in longitudinal investigations of children with ADHD who were followed into young adulthood

(23). We found no differences in patterns of comorbidity between the lifetime and persistent ADHD groups. The strength of the association between ADHD and bipolar I disorder, however, was more evident in the persistent cases. This suggests that bipolar disorder more frequently occurs with more severe forms of ADHD. While the 5% rate of bipolar I disorder in the group with persistent ADHD is lower than that described in clinical studies

(24), it is significantly higher than seen in the general population.

The ADHD subjects demonstrated earlier onsets for major depressive disorder, dysthymia, oppositional defiant disorder, and conduct disorder. Although recalled retrospectively, the mean ages at onset for oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder are consistent with descriptions of earlier onset of disruptive behavior disorders in ADHD-affected youth

(25). The mean ages at onset for major depressive disorder and dysthymia, however, do not extend to childhood, suggesting that these disorders are not continuations of pediatric psychopathology. Nonetheless, it appears that ADHD subjects are vulnerable to earlier development of adult depressive disorders. In contrast to other authors

(9–

11), we did not confirm a lower age at onset for substance use disorders, although the rates of substance use disorders were higher than that for the unaffected subjects.

A higher rate of oppositional defiant disorder in both lifetime and persistent cases of the combined ADHD subtype is consistent with findings in previous studies

(13,

14). Among subjects with persistent ADHD, the results are consistent with the hypothesis that individuals with the combined subtype show greater conduct disorder and substance use disorders and inattentive individuals show more internalizing disorders

(14). Hyperactive/impulsive symptoms decrease over time

(22). Adults meeting the full threshold for the combined subtype might represent the most severe cases of childhood ADHD and be at particular risk for impulse control difficulties. Differences found in the persistent inattentive subtype are more difficult to interpret. Adults currently diagnosed as having the inattentive subtype might have no history of hyperactive/impulsive difficulties or, alternatively, be one hyperactive/impulsive symptom short of the combined subtype. It is noteworthy that more significant differences in psychopathology were evident among subjects with persistent cases. Additional research identifying key differences in processes underlying the two main dimensions of ADHD are needed.

To our knowledge, this is the largest study to date of psychiatric comorbidity and adult ADHD in a nonclinical study group. There are several advantages to its design. Adults were identified through a study of multiply affected ADHD siblings. As such, the subjects are likely to represent more genetic cases of ADHD

(26). Although not independent, comparison of ADHD cases with unaffected parents inherently controls subjects for age and socioeconomic status and minimizes group differences due to recall bias. This study had several limitations. Parents might have more readily endorsed ADHD symptoms in light of having affected children. However, other studies that have examined this possibility found no evidence suggesting reporter bias

(27,

28). Families were recruited only if both biological parents were available. Participating adults were therefore more likely to be associated with intact families. Families with the most dysfunctional parents would be ineligible to participate, and the rates of reported comorbid psychopathology might underestimate the true incidence of psychopathology. The diagnoses were retrospective. Although retrospective assessment of adult ADHD has proven valid in clinical, family, neurobiological, and outcome studies

(29), different results might emerge from a prospective study of DSM-diagnosed ADHD children. Finally, while using unaffected parents as comparison subjects had advantages, the study did not control for other factors that might affect rates of comorbidity. For example, the rates of major depressive disorder for ADHD and non-ADHD subjects were significantly higher than in the general population. Our study did not assess the relationship between raising multiple ADHD children and development of parental psychopathology.

This study has implications for clinical practice and research. High rates of psychiatric comorbidity in the estimated 4% of adults with ADHD are a major public health concern

(1). Parents of ADHD children have a greater risk not only for ADHD but for other emotional disorders that might adversely affect parenting. Ongoing efforts in clinical education must emphasize consideration of comorbid psychopathology in assessment of adult ADHD, as well as consideration of ADHD in the evaluation of other psychiatric disorders, such as depression or anxiety. Further research is required to determine if increased psychopathology results from independent biological susceptibilities associated with ADHD, if comorbid psychopathology emerges as a developmental consequence of ADHD, and if continuous treatment of ADHD reduces adult comorbidity. Longitudinal studies of children with DSM-diagnosed ADHD are necessary to determine true rates of comorbid psychopathology in unbiased subject groups. Research is also warranted to identify potential interventions that decrease the risk for comorbidity in ADHD and to provide the empirical data necessary to support clinical treatment of complicated cases.