Case-Control Studies

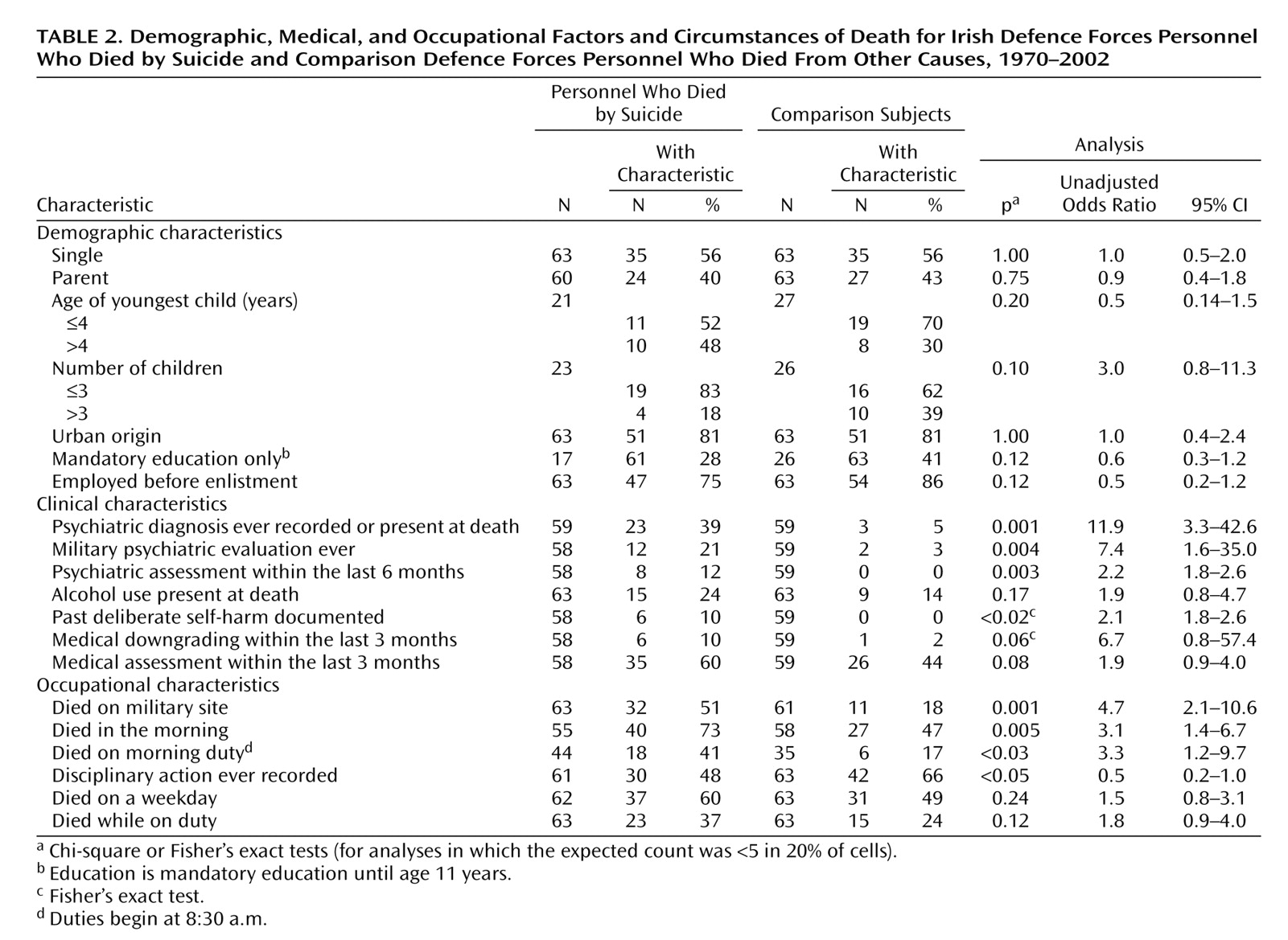

Private rank was significantly overrepresented among the personnel who died by suicide, compared to other ranks (e.g., noncommissioned officers and officers), and this result was similar to international findings

(5,

12,

17). Possibly because they had less access to firearms

(39), naval personnel who died by suicide more often chose an accessible ubiquitous means, suicidal drowning.

The finding that suicidal intent was articulated by several personnel who eventually died by suicide (N=12) requires cautious extrapolation. Reports of suicidal intent were probably more reliably elicited in inquiries into firearm suicides, as deaths following expression of suicidal intent tended to occur on military installations and while the person was on duty (N=8). These findings may have implications for psychiatric referral/assessment or for a “buddy system,” as deployed in many U.S. units

(40), to facilitate earlier detection and intervention.

Evidence-based guidelines in the assessment of suicide risk in weapon-bearing personnel might aid military psychiatrists. Our bivariate analysis, echoing data from other studies, highlights the contribution to military suicide of psychiatric indicators and psychiatric illness

(7,

41,

42), particularly alcohol misuse problems

(43). The temporal association between suicide and prodromal signs of mental illness

(44), relationship difficulties (mostly marital/sexual), civilian legal actions

(5,

12,

45), feared medical boarding (discharge)

(46), and recent reprimand or punishment were also important. In the Irish forces, as in many others, personnel are referred to psychiatrists by medical officers, not by commanding officers. In our study, personnel with psychiatric diagnoses who died by suicide included 10 subjects with affective disorders (43% of those with psychiatric diagnoses), seven with alcohol misuse (30%), one with anxiety (4.3%), and only two with psychotic spectrum disorders (8.7%). A study of occupational dysfunction due to mental disorder in the U.S. military in the 1990s revealed that by 1995 mental disorders had become the second leading cause of hospitalization

(47). The most common primary diagnoses over the study period were substance misuse, adjustment disorders, affective disorders, and personality disorders. Nine percent of outpatient visits were attributed to mental disorder. Hospitalization or outpatient care for mental disorder was highly correlated with military attrition. Reduced suicide rates associated with a suicide intervention program in the U.S. Air Force were recently reported

(48). The program prioritized early prevention, early intervention, improved treatment, and risk detection. Fundamental to the approach was the reduction of stigma in order to encourage help-seeking behavior. Military personnel may be reluctant to seek help, because concealment of psychiatric illness at enlistment can result in subsequent administrative discharge

(24). In many forces, attempted suicide and deliberate self-harm contravene military law

(49). Psychiatrists may be perceived as those who impose occupational restrictions, including perhaps denying access to weaponry

(24), thus contributing to a “professional humiliation” factor. In our study, 60% of the subjects who died by suicide had consulted a doctor in the 3 months before death. Incorporation of mental health screening in annual and pre-overseas medical examinations and in all consultations might therefore help foster healthier personnel.

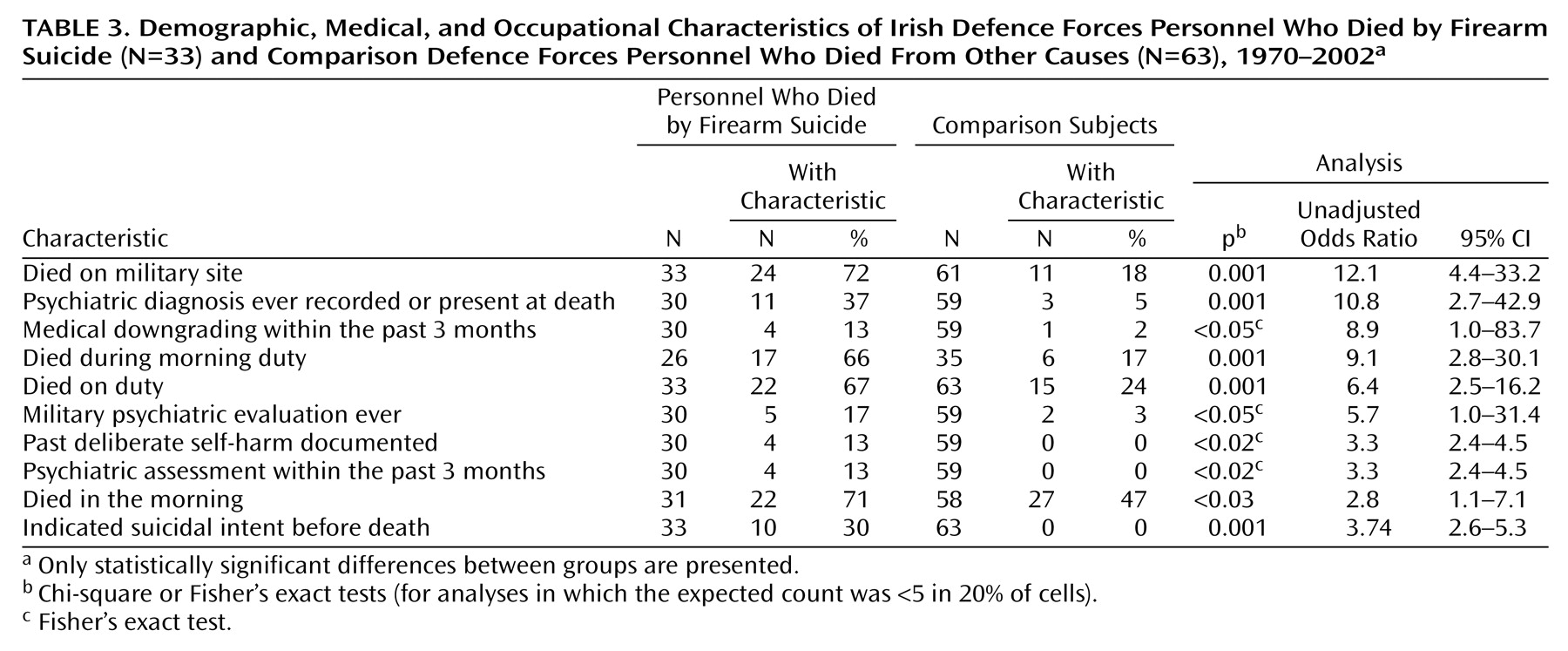

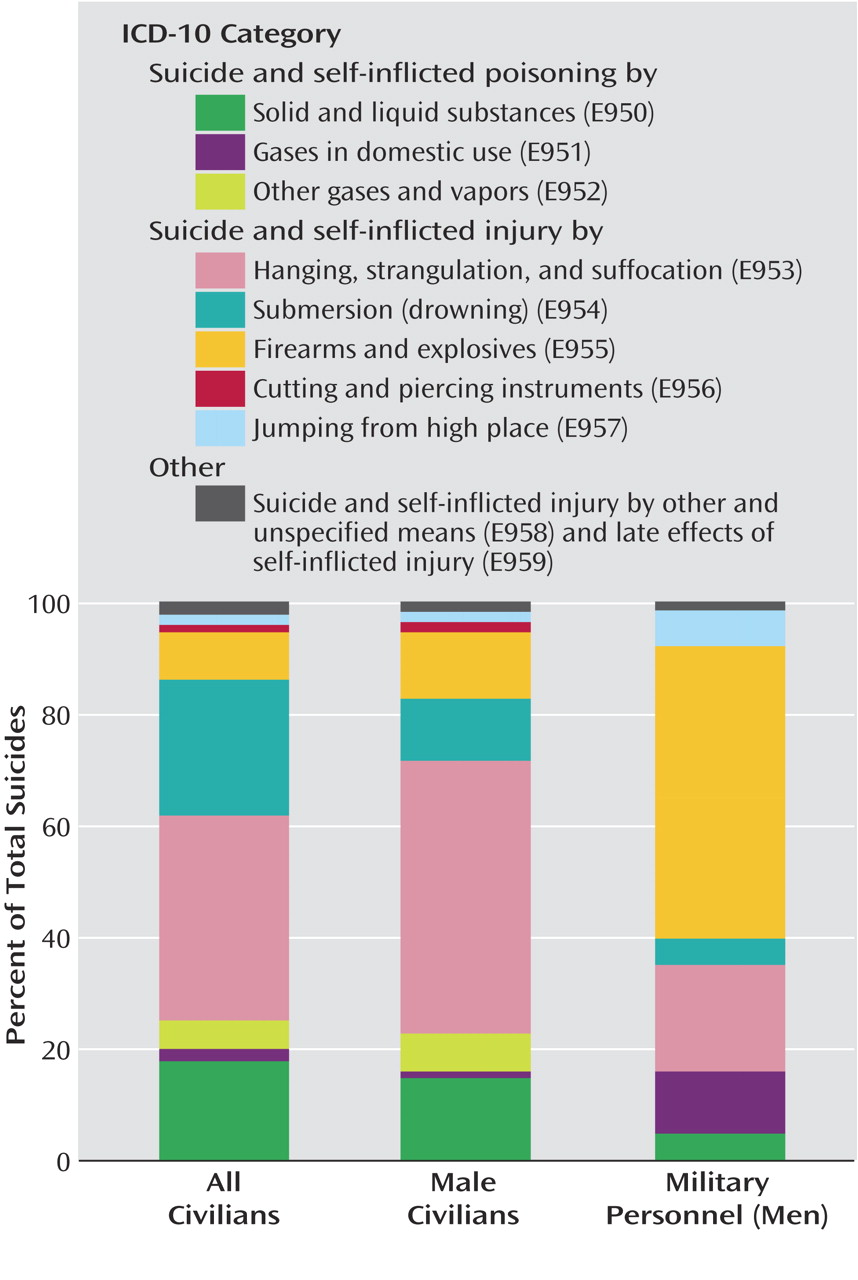

Evidence suggests that reduced access to firearms and other methods lower civilian suicide rates

(50–

52). Firearms are a necessary military occupational hazard, yet only a few studies of the efficacy of military suicide reduction strategies exist

(48,

53–55). Safer workplaces (military sites) should allow only minimal authorized and necessary access to and reduced opportunity to use such occupational hazards as weaponry and ammunition and should prevent personnel from being alone with armed weaponry. Distinctly realizable targets in any risk reduction strategy include reducing the extent of weapon bearing (reducing the number of personnel who carry firearms or the frequency of armed duties), supervision of personnel who bear weapons, and consideration of the weapon bearer’s profile (age, history of psychiatric illness and past self-harm), together with the reduction of occupation-specific stresses. Military authorities should ensure adherence on all installations to the separation of ammunition and weaponry. Stringent protocols should be followed regarding who may have access to either ammunition or weapons or both and regarding the supervision of such personnel. Ammunition accounting protocols and possible use of metal detectors could minimize stockpiling of ammunition or weapons.

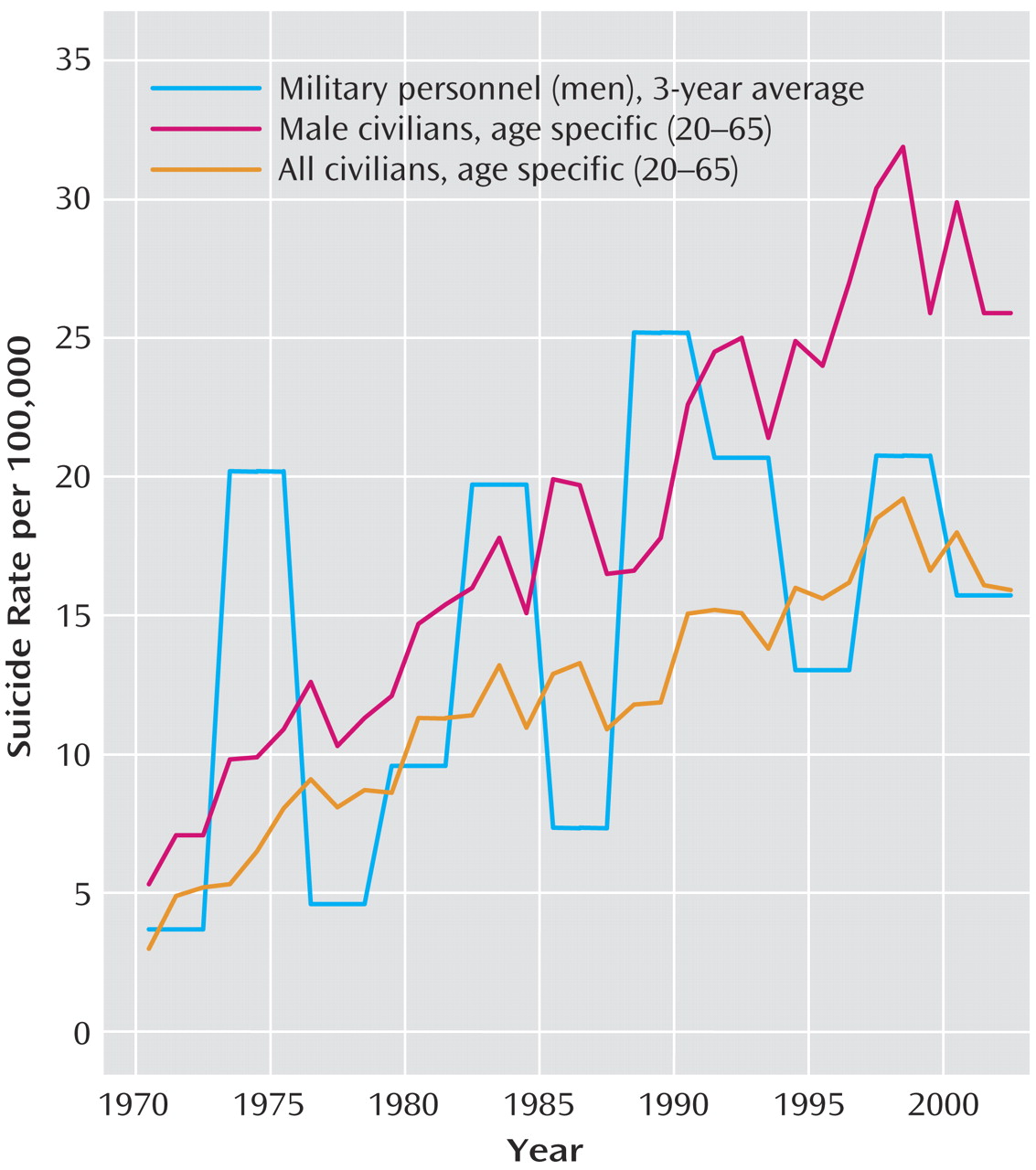

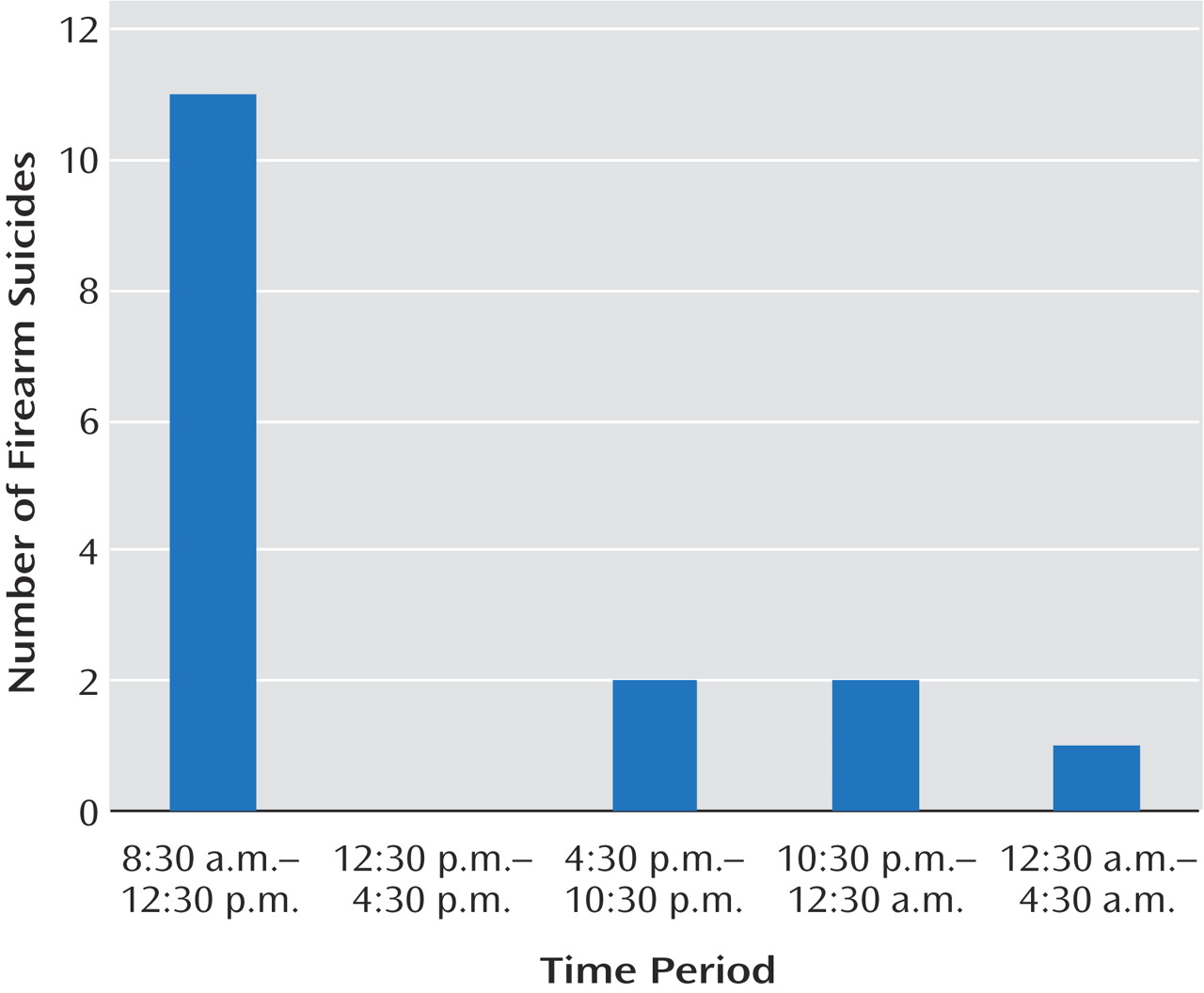

The uneven suicide risk distribution over time within periods of weapon access (shown in

Figure 3) among military personnel who largely had advance notice of their duty schedule suggests premeditation in anticipation of such access and parallels findings in civilian groups. For example, follow-up of 238,292 U.S. handgun purchasers found that handgun purchase was associated with a substantial increase in firearm suicide risk within a week of the purchase

(56). Suicide was the leading cause of death (24.5% of all deaths) in this group in the year after handgun purchase.

Firearm suicide was associated with younger age in a large U.S. civilian study that found that firearm suicide was substantially more likely in persons younger than age 21 and in men

(33). Even though only 14% of suicides among male civilians in our study setting occurred in the 20–25-year age group, our finding that a large proportion (up to 50%) of suicides among military personnel occurred in the first 5 years of military service or in the early service period (under age 24 years) is not unique

(10–

14,

17). Consequently educational and risk reduction strategies

(55,

57,

58) should focus on this postenlistment period. Armed duties may represent less risk for more mature soldiers, who are well known to commanding officers, compared to new recruits or young soldiers.

Opportunity to use a lethal means (e.g., solitary armed duty), as distinct from access to lethal means, is an additional important variable. Minimizing suicide risk in weapon bearers could be achieved by reducing unsupervised access to armed weapons. Eliminating solitary armed duties or performing these duties under camera surveillance if they cannot be eliminated might reduce the opportunity for suicide, as evidenced in other settings

(59).

We failed to replicate the importance of suicide risk factors suggested by earlier authors, including preenlistment criminality, absent-without-official-leave (AWOL) frequency, history of disciplinary offenses

(41), and greater specialty-related firearm familiarity and access, as observed in U.S. forces

(29) among U.S. Marines, small arms technicians, and Army infantry soldiers. However, in this study, familiarity with firearms could underpin the higher proportion of firearm suicides among the suicides of military personnel that took place on a military installation, compared to the rate of firearm suicides among suicides in the civilian male population and among military personnel (N=8) who did not use military weaponry and who died off a military site.

A lower incidence of suicides among military personnel overseas might be expected because of the additional health screening of these troops. Nevertheless, peacekeepers face particular stresses, including separation from family/partners, sporadic combat situations in hostile and unfamiliar territories, constant availability for duty, alcohol use, and isolation

(60–

62). Our analysis revealed no statistically significant differences between the military personnel who died by suicide and the comparison subjects for any measure of overseas or border duty, perhaps replicating studies in peacekeepers

(5) and Vietnam draftees

(41,

63), despite differences in combat intensity.