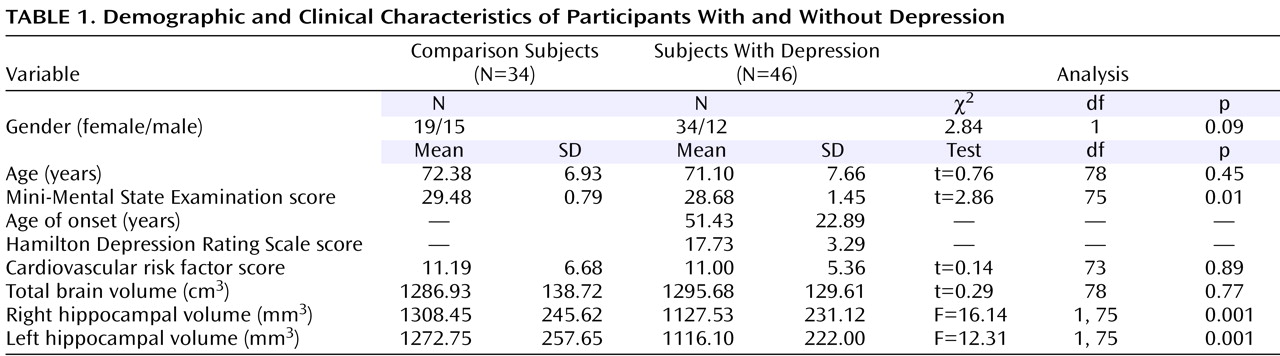

Of importance, major depression, especially in the elderly, may be considered a heterogeneous disorder because in a subset of patients, the first episode occurs only late in life. This subgroup, frequently referred to as having late-onset depression, exhibits certain unique clinical, biological, and neuroimaging characteristics. For example, patients with late-onset depression are less likely to have psychiatric comorbidity

(9) or a family history of depression

(9,

10) but are more likely to have medical comorbidity

(11) compared with groups with early-onset depression. Some evidence links late-onset depression to greater cognitive deficits

(12) and increased risk of dementia

(13,

14) ; other studies relate a lifetime history of depression to a higher risk of dementia

(15 –

17) .

Illness duration rather than age itself may predict hippocampal volumes in depressed subjects

(18) . Reduced hippocampal volumes have been associated with a longer course of illness in elderly depression

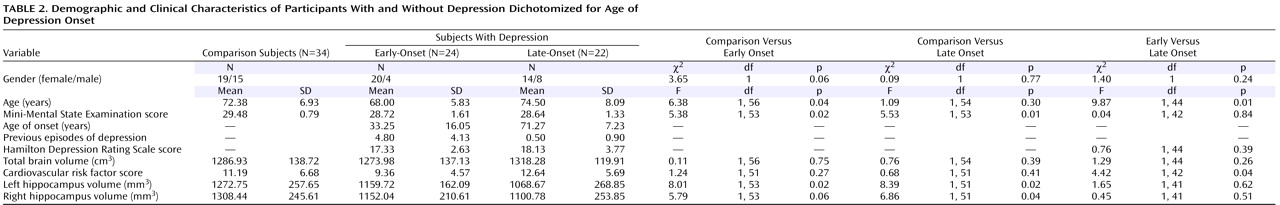

(2) . On the other hand, some studies dichotomized elders by age at illness onset and found hippocampal volume reductions more pronounced in late-onset than early-onset depression

(1,

4,

5) . Prior evidence thus suggests that age of onset and perhaps also illness duration influence hippocampal morphology in depression. It is also possible that these two measures are themselves correlated. However, because the magnitude and direction of the relationship between age of onset (or biological age in general) and illness duration are solely dependent on study group characteristics and the timing of subject examination, these two variables may be considered to constitute independent hypotheses.

Genotype may be important because smaller hippocampal volumes in late-onset depression have been linked to the long variant of the promoter region of the serotonin transporter gene

(8) . Indeed, subjects homozygous for the long allele genotype may have greater vascular risk factors and an enhanced vulnerability to stress-induced neurotoxic effects of glucocorticoids, which may both lead to structural hippocampal abnormalities

(8,

19,

20) . Moreover, the short allele has been found to moderate the influence of stressful life events on the development of depression through mechanisms that may affect hippocampal volume

(21) .

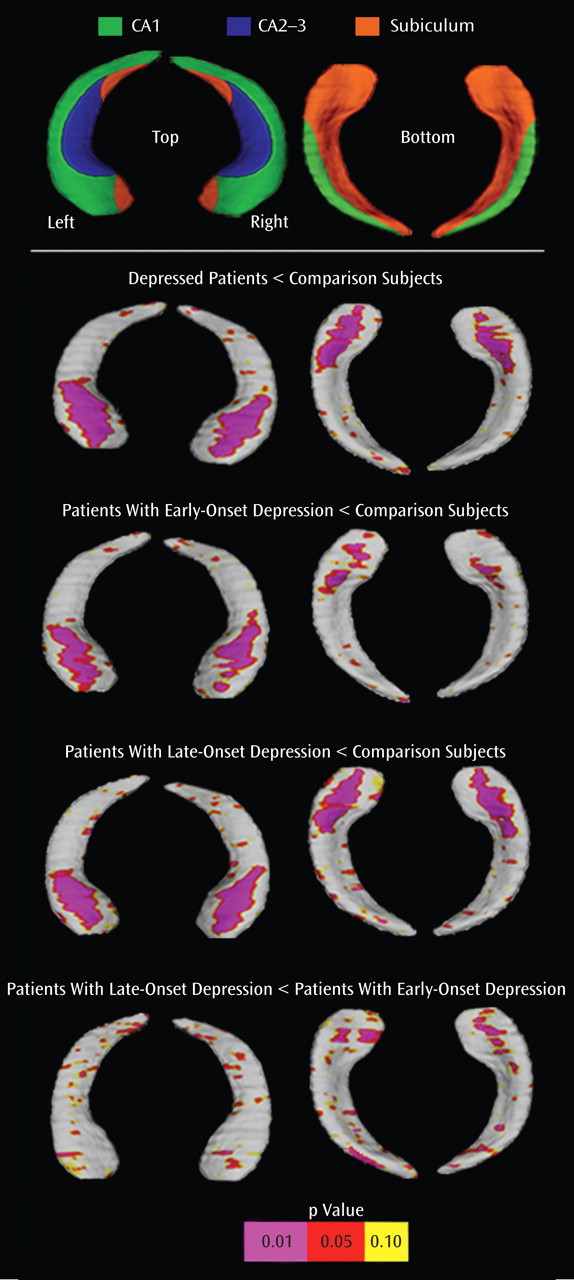

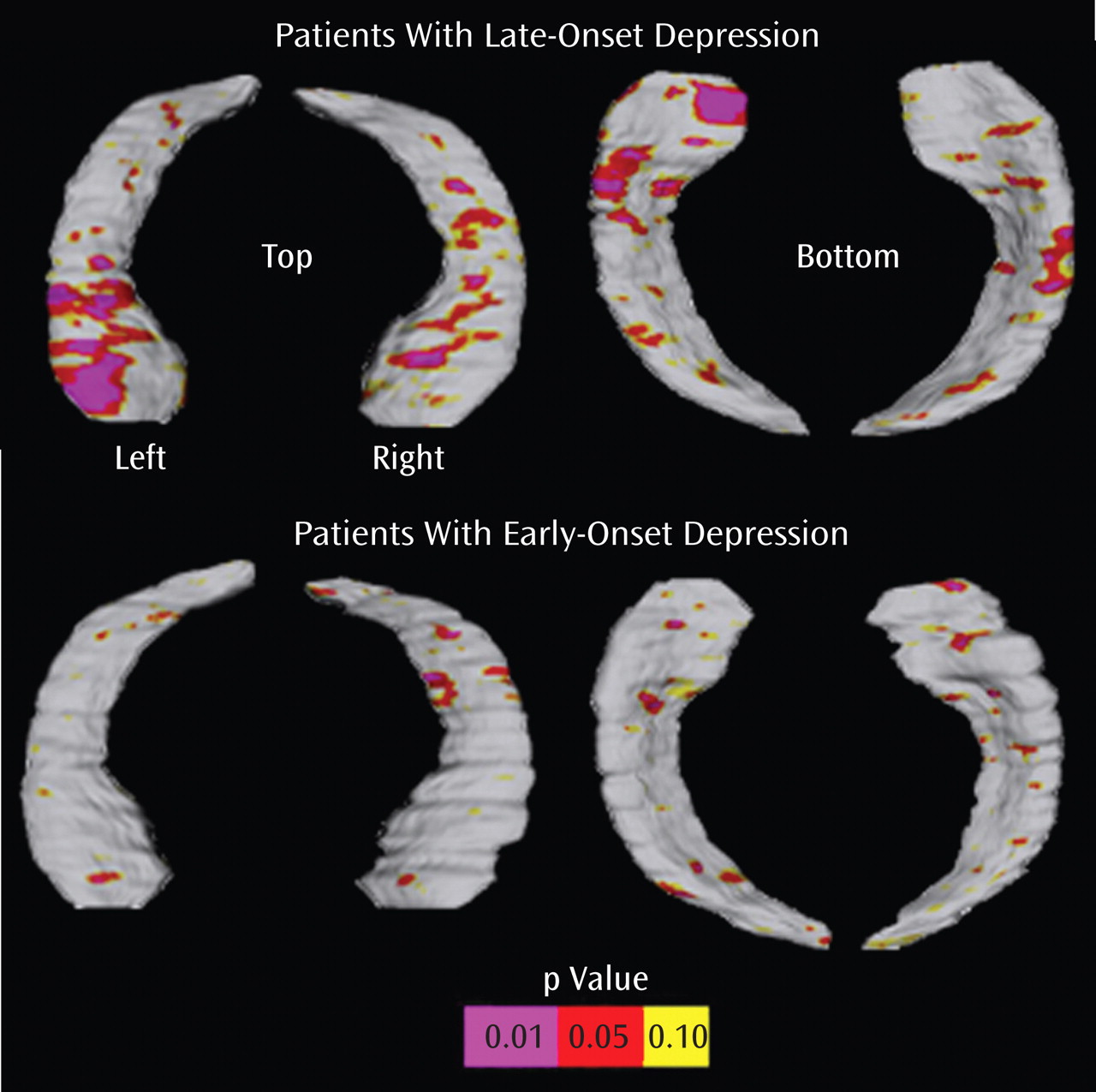

In elderly depression, however, the question of regional specificity of hippocampal volume reductions has not been addressed in the literature. The aim of our study was to use a region-of-interest technique and a hippocampal three-dimensional radial atrophy mapping approach

(23,

24) to assess subregional structural deformations in depressed elders. Specifically, we set out to examine whether late-onset depression may exhibit greater regional changes in hippocampal morphometry than early-onset depression. We also addressed possible relationships between hippocampal morphology and neuropsychological measures of memory in a subgroup of the subjects included in the present study.

Discussion

For the first time, to our knowledge, in this report, we used novel computerized surface-based image analysis techniques to isolate regional hippocampal volume deficits in elderly depression based on age at illness onset. The key findings were the following:

Significant surface contractions indexing regional volume deficits in the hippocampal head, possibly corresponding to areas in CA1-CA3 subfields and the subiculum, when the depressed cohort was examined as one group

Similar spatial patterns of significant bilateral surface contractions between patients with late-onset depression and comparison subjects and, to a lesser extent, between patients with early-onset depression and comparison subjects, with minor involvement of the subiculum

Comparison of the two disease groups revealed significant left regional hippocampal reductions in patients with late-onset depression, possibly concentrated in the subiculum and in posterior-lateral aspects of the CA1

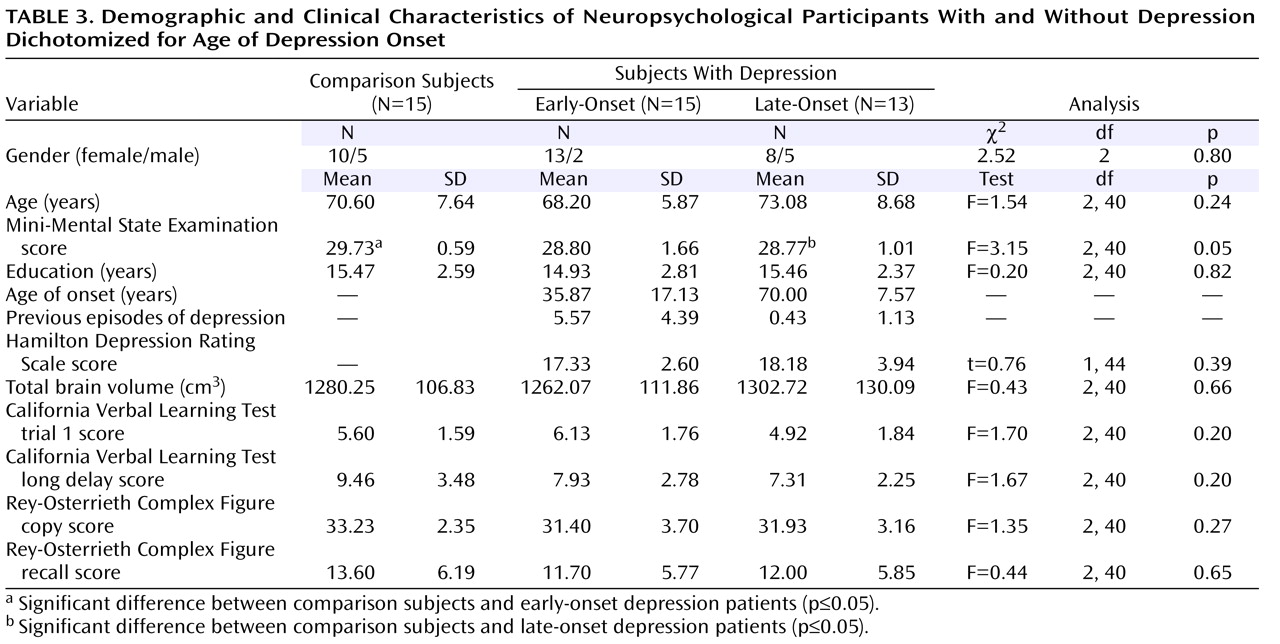

Significant relationships between hippocampal deficit patterns and memory performance among patients with late-onset depression but not patients with early-onset depression

Global volume differences were consistent with most earlier studies

(1 –

5), showing smaller hippocampal volumes in elderly depressed patients in relation to comparison subjects, although some reports have shown differences as being more pronounced for the right than for the left hemisphere

(1,

2) . Our results may support other work that dichotomized subjects by age at illness onset

(1,

4,

5) and found greater hippocampal volume reductions in late-onset depression. Indeed, in the present study, traditional volumetric analyses displayed significant differences between each disease group and the comparison group, with greater deficits in patients with late-onset depression versus comparison subjects than patients with early-onset depression versus comparison subjects, but we did not detect significant differences in global hippocampal volume between early-onset and late-onset depression. However, when computational mapping methods were applied, the two disease groups not only differed significantly from the comparison subjects but also from each other. Indeed, when effects are highly localized, maps are likely to detect regional changes in hippocampal structure that volumetric measures may miss

(22) .

Damage to particular subfields is supported by postmortem studies, revealing complex neuronal abnormalities in the subiculum

(37) as well as in distinct layers of hippocampal subfields, with highest changes in the CA1, followed by the CA2 and the CA3

(38) .

Factors that may contribute to hippocampal damage include hypercortisolemia and ischemia. Of interest, the CA1 and CA2 subfields appear especially vulnerable to vascular damage

(39), which may correspond well with our maps of local volume reductions in both early-onset and late-onset depression and with the hypothesis that especially ischemic small-vessel disease may be implicated in the pathogenesis of elderly depression

(40) . Our maps may also suggest possible damage to the CA3 subregion. Both the CA2 and CA3 subregions receive the major hypothalamic projection to the hippocampus formation. Since the hippocampus is thought to modulate the secretion of adrenocorticotrophic hormone

(41), enhanced vulnerability to damage from cortisol may at least partly reflect aberrant regulatory circuitry involving hippocampal subfields linked to the hypothalamus.

Hippocampal connections are topographically organized along the anterior-posterior axis in addition to the horizontal axis

(42) . For example, projections to and from the prefrontal cortices occur in a gradient concentrated in anterior hippocampal regions

(43) . Our prior investigations in elderly depression have shown bilateral gray matter abnormalities in distinct subregions of the prefrontal cortex, including the anterior cingulate, the orbitofrontal cortex, and the gyrus rectus

(31,

32) . Late-onset depression may be associated with greater cortical atrophy than early-onset depression, especially in temporal and parietal regions

(26) . This may offer a potential explanation for the more pronounced local volume reductions in both the hippocampal head and tail of subjects with late-onset depression compared to subjects with early-onset depression, as found in the present study.

A key finding of our study was the observation of local volume reductions concentrated in anterior aspects of the subiculum, as well as lateral-posterior aspects of the CA1 subfield in late-onset depression compared with early-onset depression. With computational mapping approaches, CA1 and subiculum involvement were found in patients with mild cognitive impairment who later developed Alzheimer’s disease

(36) . Patients with a late age of illness onset may therefore be at a higher risk of developing dementia over time. Our exploratory findings of significant interactions between regional hippocampal surface contractions and verbal as well as nonverbal memory performance in late-onset depression but not early-onset depression of a subgroup may further support this view. Three-dimensional maps of cognitive correlates of hippocampal surface morphology were more sensitive for detecting these relationships than correlation of memory scores with hippocampal volumes. Specifically, a strong correlation for the CA1 subfield and the subiculum was observed with the California Verbal Learning Test long delay in the left hemisphere among patients with late-onset depression, which may resemble patterns found in early Alzheimer’s disease

(36) . Mini-Mental State Examination scores differed significantly between patients with late-onset depression and comparison subjects in the subgroup, yet they remained within the normal range. In addition, patients with late-onset depression did not differ from comparison subjects or patients with early-onset depression in their mean delayed recall scores or any other memory measure. This may imply that regional hippocampal atrophy patterns and their associations with memory performance could become apparent before clinical evidence of cognitive decline. Hippocampal atrophy may therefore be a candidate neurobiological marker for defining risk profiles for dementia conversion. Longitudinal studies are warranted to support this hypothesis by specifically exploring the pathophysiology of structural and neuropsychological changes over time and their relation to treatment and illness course

(44) . In particular, longitudinal studies may help clarify whether patients with early-onset depression are more amenable to antidepressant treatments than patients with late-onset depression.

The limitations of this study should be noted. Despite the relatively small overall group size and the small size of the subgroups, we were able to detect significant morphological differences between groups, and significant associations between regional hippocampal volume reductions and memory performance, respectively. A larger group will better define hippocampal regions that correlate best with cognitive measures and determine the specificity and sensitivity of our methods in defining risk profiles. In addition, combined MRI and postmortem studies with prospectively gathered clinical information about depressive symptoms and cognitive function would help elucidate the link between changes seen in MRI and an underlying neuropathology (e.g., Alzheimer’s disease) that may cause depression. Without direct pathological validation, the interpretation of the subregional involvement remains arbitrary. The subregional boundaries that we used were similar to those proposed by other research groups

(22,

45) . Nevertheless, what we interpret as specific regional involvement may reflect changes in another hippocampal region. In addition, study groups were not optimally matched for age and gender. However, our analyses included age, gender, and total brain volume as covariates, thus reducing the possibility of confounding effects.

In conclusion, we mapped hippocampal volume deficits in elderly depression, showing prominent local reductions in CA1-CA3 fields and the subiculum. This study is also the first to our knowledge to show that concentrated volume reductions in the CA1 and the subiculum distinguish late-onset from early-onset depression. In addition, we provided preliminary evidence for a significant association between hippocampal surface contractions and memory performance among patients with late-onset but not early-onset depression. Identifying regional abnormalities in hippocampal structure may thus help dissociate possible neuroanatomic vulnerabilities to illness progression based on age at onset, thereby offering potentially new perspectives for defining appropriate interventions.