In this study, we addressed the common problem of inadequate sample size in investigating subgroup differences by combining two major national surveys, the NCS-R and the National Latino and Asian American Study (NLAAS), using complementary sampling and assessments. We then tested whether the immigrant paradox applies to all Latino groups by comparing national lifetime prevalence of DSM-IV psychiatric disorders among immigrant Latino subjects, U.S-born Latino subjects, and non-Latino white subjects.

Discussion

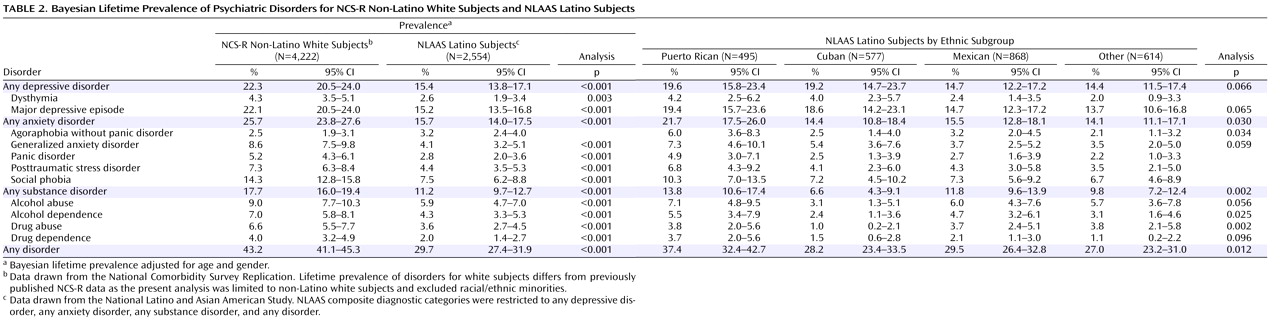

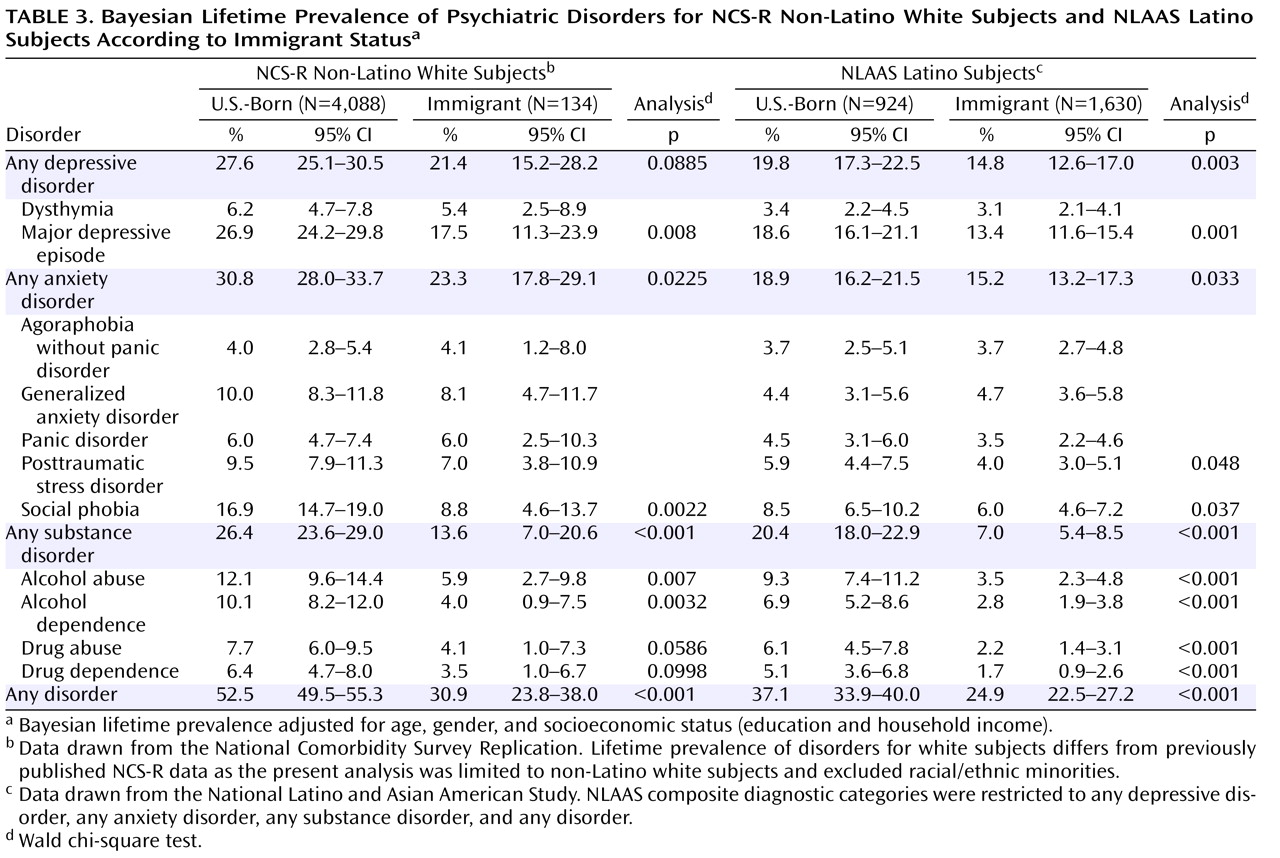

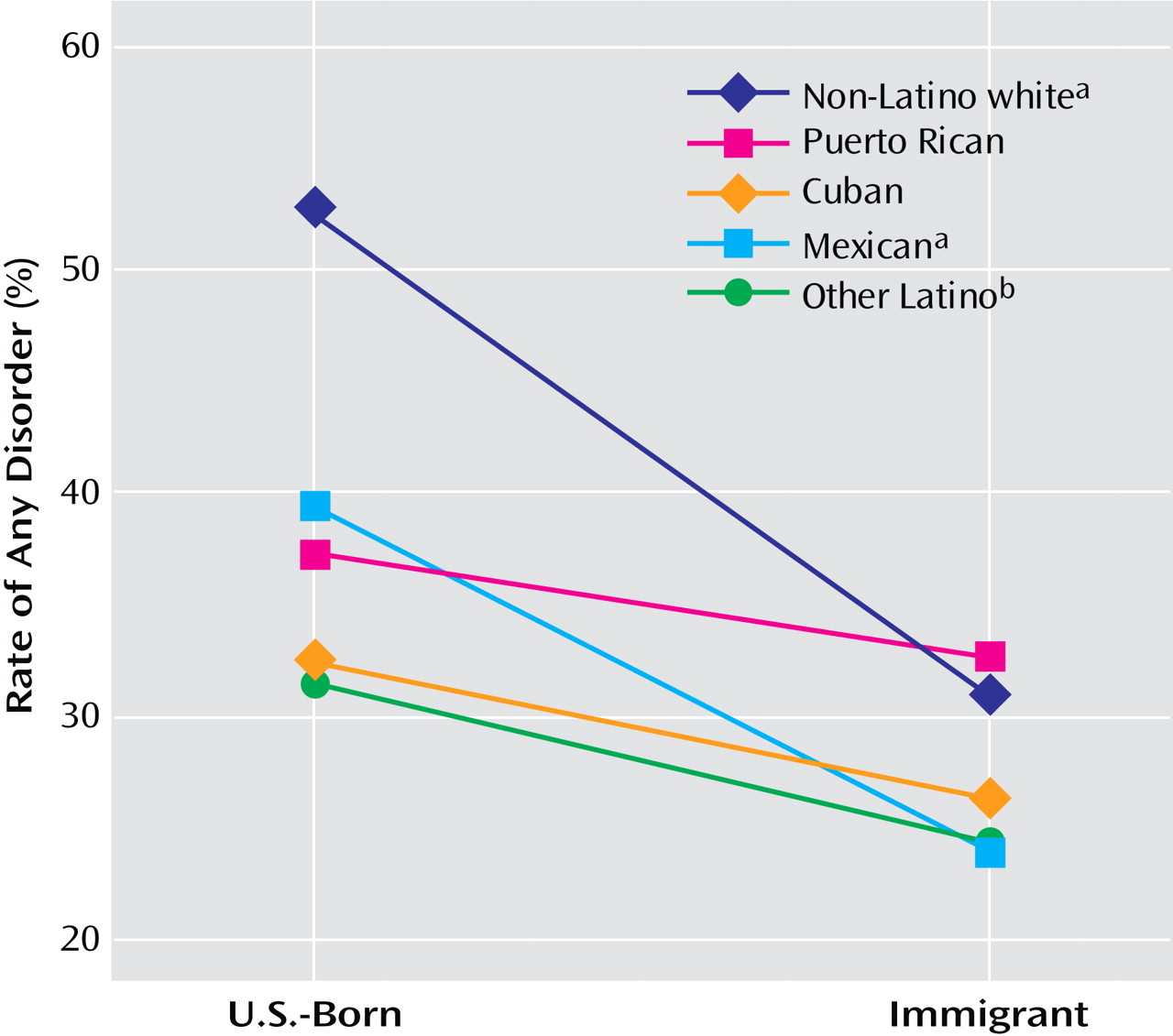

When lifetime prevalence estimates of psychiatric disorders are examined for the aggregated Latino sample, our findings are consistent with existing literature. First, Latino subjects were at lower risk of all lifetime psychiatric disorders compared with non-Latino white subjects, except for agoraphobia without panic disorder. Second, consistent with the immigrant paradox, U.S.-born Latino subjects reported higher lifetime rates for most disorders than Latino immigrants. These higher rates are not surprising, given that psychiatric disorders are more prevalent in the United States than in many other parts of the world

(26) . Contexts and lifestyles unique to the United States appear to result in higher rates of psychiatric disorders.

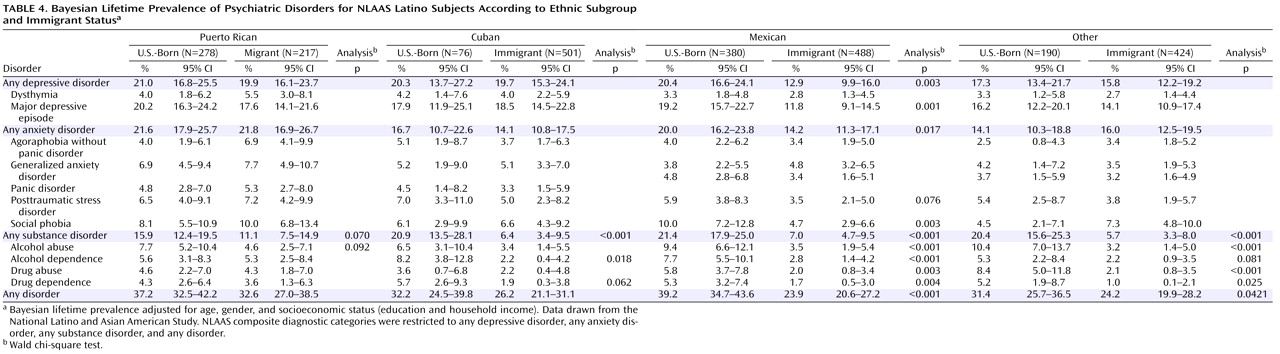

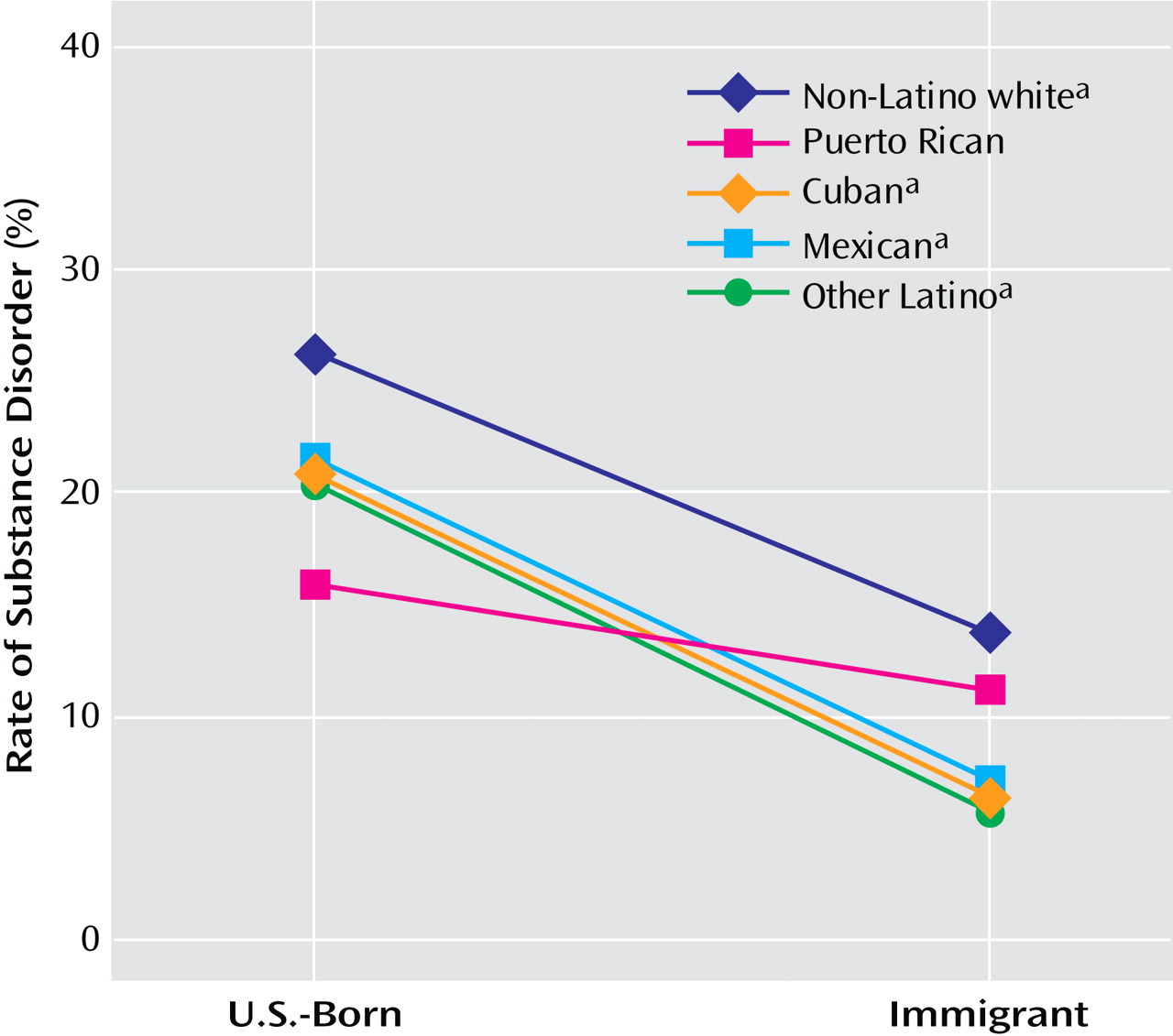

However, when our sample was disaggregated into ethnic subgroups and by nativity, a more complicated picture of Latino mental health emerged, exhibiting a more limited application of the immigrant paradox. Overall, the immigrant paradox was only reliably observed for Mexican subjects, and only evident for depressive and anxiety disorders. However, the paradox was consistently observed among Mexican, Cuban, and other Latino subjects for substance disorders. No evidence for the immigrant paradox was found among Puerto Rican subjects. These findings have significant implications for the assessment and treatment of psychiatric disorders within the U.S. Latino population. Our findings emphasize the importance of not generalizing the protective effect of nativity for all Latino individuals and the differential effect of nativity, depending on the type of disorder.

The immigrant paradox was most strongly apparent for substance disorders. The protective impact of foreign nativity on lifetime prevalence of substance disorders for most immigrants, particularly Latino immigrants, could be related to strong social control against alcohol and drug use in their countries of origin

(27) . International comparisons of prevalence rates of substance use disorders across different cultures indicate that cultural and social assimilation and longer stays in cultures with high rates of drug use accelerate the rates of substance use disorders for immigrant groups from nations with lower rates

(27) . Puerto Rican individuals are U.S. citizens, which makes their migratory patterns and exposure to U.S. culture different from those of other Latino groups. Our findings thus suggest that immigrants benefit from a protective effect in their country of origin, which possibly inoculates them against risk for substance disorders, particularly if they emigrate as adults. Recent findings also suggest that where Latino immigrants reside in the United States is an important influence on risk of substance disorders

(28) . For example, a higher perceived level of neighborhood safety is associated with lower risk for substance use disorders, even after controlling for individual-level socioeconomic status

(28) .

The question that remains to be answered is what factors in U.S. society place the U.S.-born population and those who emigrate early in childhood at greater risk for substance abuse. The easy availability of drugs in the United States may be one contributing factor. However, greater availability of drugs in the United States alone cannot explain these results, since countries like Mexico, with extensive drug production and trafficking, consistently show low rates of substance use disorders

(6,

29) . One hypothesis involves the U.S. societal convention of self-medicating as a way of coping with hardship

(30) . U.S. cultural norms, such as pressure to be productive at work and overprescription of medication, are thought to fuel recent increases in self-medication in the United States

(31) . In other countries, different coping mechanisms may be socially prescribed. In one study, Mexican citizens were found more likely than non-Hispanic white individuals to use positive reframing, denial, and religion and less likely to use substances

(30) .

Table 4 presents evidence that, for depressive and anxiety disorders, only Mexican subjects experienced the immigrant paradox. There could be several explanations for this. Mexican immigrants experience relative deprivation and inequality in their country of origin

(32) . These experiences may decrease the likelihood of demoralization among Mexican immigrants in their new environment

(1,

4) and increase resignation to negative outcomes, resulting in lower risk of depression and anxiety. Traditional family values of affiliation, as well as fatalism, may serve as protective factors against psychiatric morbidity in the Mexican population

(1,

4,

33) . However, the buffering effect of these factors does not translate to other Latino ethnic subgroups

(6) . In these groups, confronting social injustice, low opportunities for social mobility, and hardship may be internalized as personal failures

(34), thereby leading to depression and anxiety. An alternative explanation is that Mexican families, because of their proximity to Mexico, have less intergenerational conflict between family members

(35) than other Latino subgroups, allowing for a sustained sense of belonging that can buffer adversity. Another explanation is that Mexican immigrants, because of their high numbers in the United States and because they tend to arrive at an older age, may be less likely to intermingle with non-Latino individuals in multiple settings, decreasing exposure to cultures different from their own and possibly reducing the likelihood of incidents of discrimination

(36) . This decreased exposure to perceived discrimination may relate to lower rates of depression and anxiety when compared with other Latino groups such as Puerto Rican migrants, who come to the mainland United States earlier and tend to live in more ethnically diverse neighborhoods.

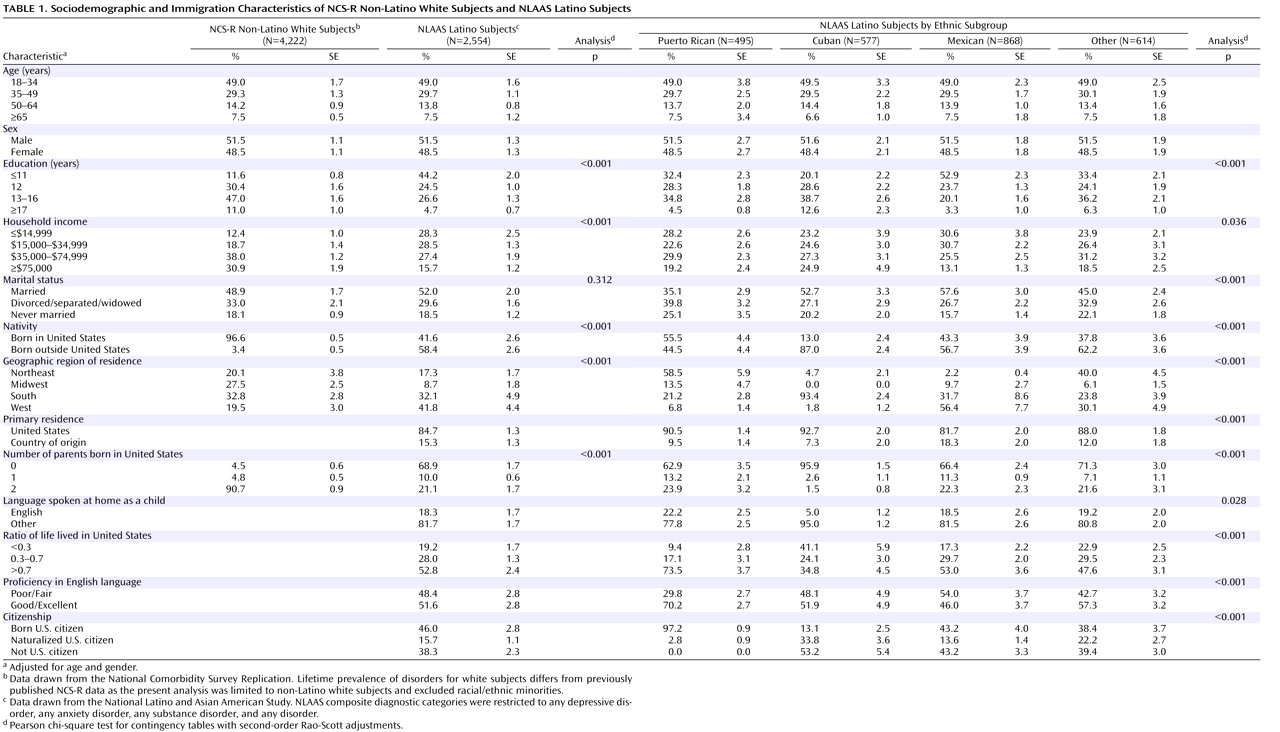

In addition to providing valuable data on the presence of the immigrant paradox, our findings also provide insight into the large subgroup variability within the U.S. Latino population. The data presented in

Table 1 and

Table 2 show significant variation by ethnic subgroup for sociodemographic characteristics and for lifetime risk of psychiatric disorders, with Puerto Rican subjects as a particularly vulnerable group. In contrast to the other Latino groups, the Puerto Rican population has lived with more than a century of influence from the United States and is more likely to be bilingual and to have adopted many U.S. lifestyle patterns

(37) . This high degree of integration into U.S. culture may explain the similarity in rates of disorders between Puerto Rican subjects and non-Latino white subjects. Furthermore, the first Puerto Rican migrants, although U.S. citizens, came into the United States stigmatized by the public perception that they emigrated because of massive unemployment and the desire to be supported by welfare

(6), which perhaps subjected them to more discrimination and stereotyping than other Latino ethnic subgroups

(6), resulting in higher rates of psychiatric disorders. Our findings provide further evidence that the common practice of aggregating Latino ethnic subgroups into a single group masks great variability in the prevalence and risk of psychiatric disorders.

This study has certain limitations. Our results are based on cross-sectional comparisons of Latino and non-Latino white subgroups, which could mask cross-generational differences that explain some ethnic subgroup differences. The reported lifetime prevalence rates in this study could be even higher if Latino subjects with severe mental illness were overrepresented in the nonresponse group, since severe disorders such as bipolar disorder and schizophrenia were not included in this study. We did not measure the prevalence of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder because lay-administered diagnostic interviews substantially overestimate the prevalence of schizophrenia

(38), and meaningful estimates for bipolar disorder were considered too difficult due to low prevalence in community samples

(39) . Another potential limitation is that the diagnostic interview seems to require substantial education to comprehend some of the more elaborate probes. If Latino respondents with low levels of education and literacy did not understand the questions, they might have reported not having the symptom; thus the prevalence rates reported here may be conservative estimates of psychiatric disorders in the Latino population. However, this seems unlikely since we found the same differences after adjusting for education. Finally, as with many studies in which many specific comparisons are made, one must be mindful of the nature of multiple comparisons and be careful not to focus too much on a particular finding, since the probability that the finding is due to statistical chance is non-negligible.

In the field of mental health research, it is commonly believed that Latino populations are at lower risk of psychiatric disorders than the foreign-born non-Latino white population. As a result, Latino individuals, in particular Latino immigrants, have been largely ignored in mental health research and the development of treatment interventions

(40) . However, our results demonstrate that within the Latino population, some subgroups suffer from psychiatric disorders at rates comparable to non-Latino white individuals. Therefore, we urge caution in generalizing the immigrant paradox to all Latino groups, since the protective effect of nativity varies by type of psychiatric disorder and subethnicity. Studies that fail to disaggregate into Latino subgroups may be inaccurately reporting the immigrant paradox as a universal phenomenon, thereby overlooking the risk experienced by some immigrant groups. In order to guide effective and culturally appropriate prevention and treatment efforts, it is critical to identify and understand the specific components of various cultures that are protective against psychopathology, as well as those factors that increase risk of psychiatric morbidity.