Acute and Tardive Akathisia

Akathisia is one of the most common acute movement disorders

(1), but it also exists in chronic and tardive forms. These akathisia variants are less well recognized but are equally—and sometime more—debilitating to patients. The word “akathisia” (derived from Greek, literally meaning “not to sit”) was first used in 1901 by Haskovec

(2) to describe two patients who experienced restlessness and an inability to sit still. In contemporary usage, akathisia refers to a drug-induced movement disorder. Akathisia presents as a syndrome of motor restlessness, usually in the lower extremities, that is often (but not always) accompanied by a subjective sense of inner restlessness, an urge to move, and anxiety or dysphoria

(3) .

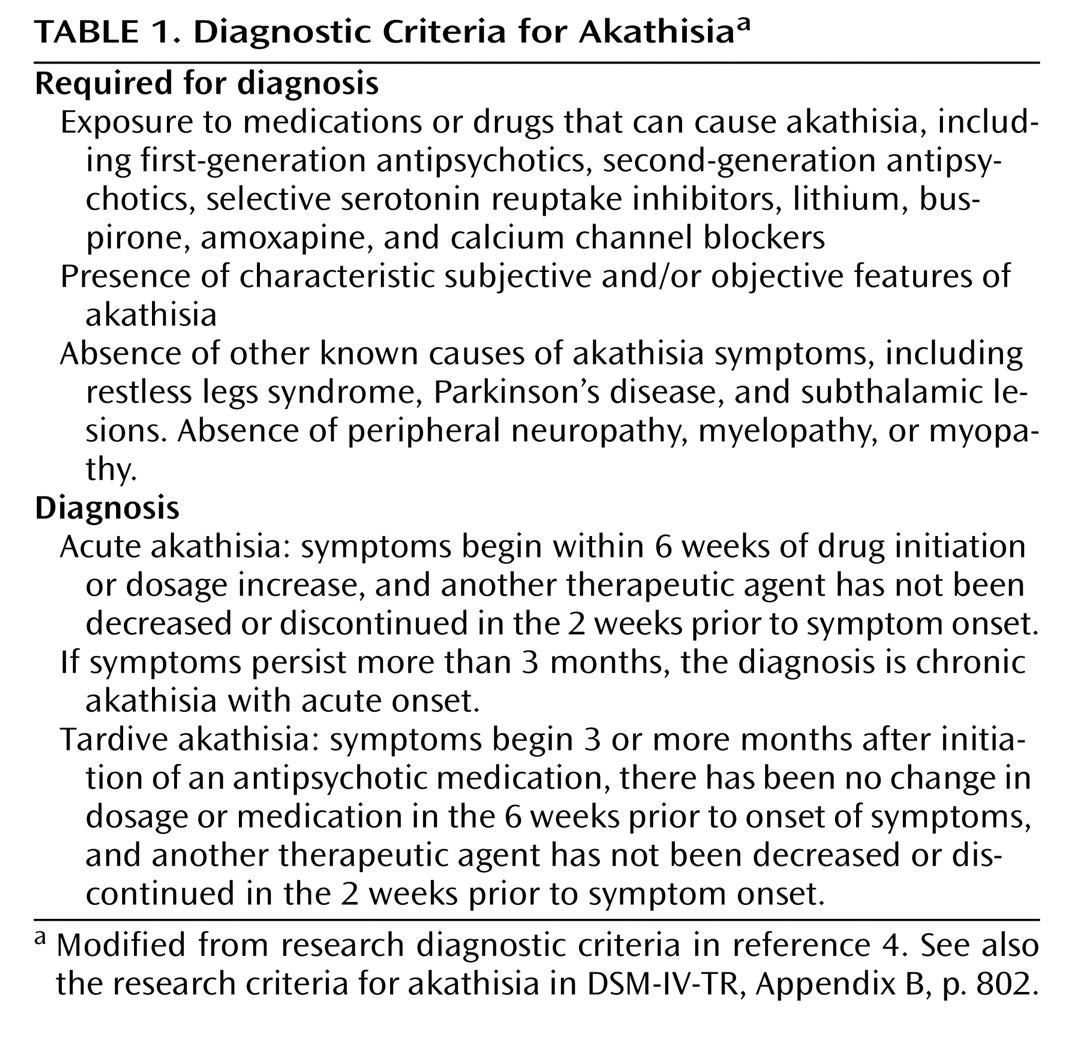

Most cases of akathisia are acute and are dose related (

Table 1 ). Chronic akathisia is defined as akathisia persisting more than 3 months after the last antipsychotic dosage change; it does not address acuity of onset

(4) . Tardive akathisia has a delayed onset, with symptoms beginning 3 months or more after medication initiation or dosage increase

(4) . Some patients, such as the patient presented in the clinical vignette, demonstrate an “unmasking” or worsening of symptoms with drug withdrawal and an improvement with dosage increase. This is often referred to as “withdrawal akathisia”

(4) . Tardive akathisia often persists even in the absence of antipsychotic medication. Burke et al.

(5) reported akathisia persisting for an average of 2.7 years in 26 patients whom they followed after discontinuation of antipsychotic medications.

Pathophysiology of Akathisia in Schizophrenia

The pathophysiology of akathisia is poorly understood, but it appears to differ from that of extrapyramidal symptoms. The prevailing hypothesis for both is that the symptoms are due to antipsychotic-induced dopamine D

2 receptor occupancy above a threshold of 80%

(9) . However, in individual patients there is not a clear relationship between the severity of akathisia and other extrapyramidal symptoms, such as rigidity and tremor. This suggests that the striatonigral dopamine pathway involved in the pathophysiology of extrapyramidal symptoms is unlikely to be the main pathway in akathisia

(10) . Cholinergic and adrenergic pathways may play a mediating role

(10) ; in both cases, the majority of available evidence for their involvement comes from the clinical utility of anticholinergic and antiadrenergic (b

2 antagonists) medications in improving akathisia

(10) . Similarly, second-generation antipsychotics with high cholinergic receptor affinities carry a lower risk of akathisia

(9) . Investigators have hypothesized that serotonergic pathways may be implicated, because serotonergic medications, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, can induce akathisia, and antagonism of serotonin (especially 5-HT

2A ) by some second-generation antipsychotics can reduce akathisia symptoms

(10) .

Diagnosis

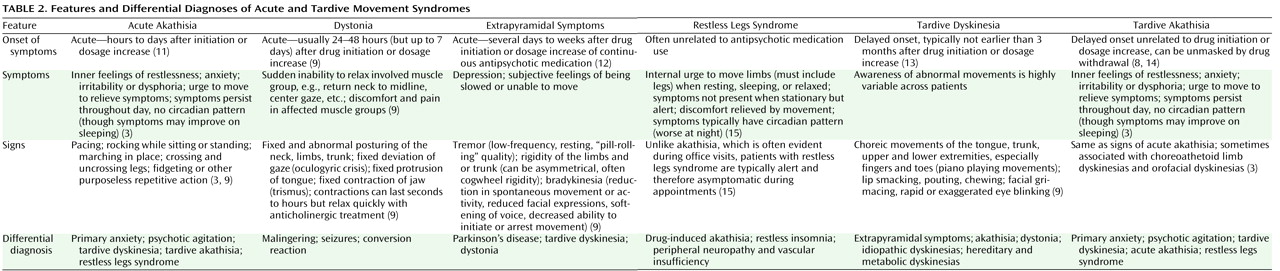

Table 1 lists the diagnostic criteria for akathisia, and

Table 2 presents the features and differential diagnoses of various movement syndromes.

The diagnosis of akathisia can be difficult

(16), particularly since the medications most often implicated in akathisia are those most likely to have been prescribed for treatment of psychotic agitation. Akathisia is often mistaken for anxiety or worsening of psychotic agitation, and anxiety and agitation often accompany akathisia and further complicate the differential diagnosis. Another factor complicating diagnosis is that akathisia symptoms can vary in severity over time, particularly in mild cases. The assessment of akathisia in clinical trials usually involves rating scales that may include measures of both subjective and objective components. The most widely used scale today is the Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale

(17) . Although akathisia scales have demonstrated reliability and validity, investigators are rarely well trained in their use, and interrater reliability is seldom established in large multicenter trials, making it difficult to develop accurate estimates of incidence, prevalence, and risk factors. Furthermore, akathisia can often be suppressed with distraction; if clinicians are monitoring for akathisia only under brief and formal examinations, the diagnosis may be overlooked

(1) .

Restless legs syndrome and akathisia have many symptoms in common

(15,

18), and direct-to-consumer marketing of medications for restless legs syndrome may lead to confusion of this disorder with akathisia. Making the distinction is critical, because the treatment for restless legs syndrome (dopamine agonists such as ropinirole and pramipexole

[19] ) may worsen psychosis, necessitating higher dosages of antipsychotic medication and ultimately worsening the akathisia. We have included a column on restless legs syndrome in

Table 2 to aid in making the diagnostic distinction. The important distinguishing features of restless legs syndrome are that symptoms usually occur only during periods of rest, relaxation, or sleep and that the symptoms follow a circadian pattern and are typically worse in the evening or at night

(15) .

Differentiating tardive akathitic movements from tardive dyskinetic movements can also be difficult, especially in circumstances where both conditions may be present. Tardive akathisia can share features with tardive dyskinesia. A study of akathisia in patients taking first-generation antipsychotics found that one-third to two-thirds of those with tardive akathisia had either orofacial or choreoathetoid limb dyskinesias suggestive of tardive dyskinesia (3). It is unclear whether tardive akathisia is a separate disorder or a variation of the manifestations of tardive dyskinesia (6). The choreic movements of tardive dyskinesia should be distinguished from some of the more complex and rare manifestations of akathisia, including face and thigh rubbing, scratching, and trunk rocking (1). There are several important distinguishing features. The first is that tardive akathitic movements can be voluntarily suppressed, at least briefly. The second is that akathitic movements are complex and demonstrate an intact motor control

(4) .

First-Generation Versus Second-Generation Antipsychotics

When chlorpromazine, the first widely used antipsychotic, was introduced in 1954, the potential for a variety of extrapyramidal side effects quickly became apparent. (In fact, some observers

[23] suggested that parkinsonian side effects, specifically micrography, could be used to detect the dosage threshold for antipsychotic efficacy.) The assumption that antipsychotic drug treatment had to come with a high risk of movement disorder was challenged with the introduction of clozapine, the first antipsychotic medication that had a qualitatively lower risk of inducing extrapyramidal side effects

(24) .

Between the 1960s and the 1980s, much was learned about the incidence, prevalence, and risk factors for neuroleptic-induced movement disorders—acute dystonic reactions, akinesia, motor rigidity, tremor, akathisia, and tardive (or late-occurring) syndromes such as tardive dyskinesia, tardive dystonia, and tardive akathisia. Throughout these decades, however, a number of investigators continued to voice concern that these disorders were often missed completely, falsely attributed to psychopathology and undertreated, even when diagnosed

(20,

25,

26) . The consequences of these disorders were often significant in terms of personal distress, functional impairment, stigmatization, and nonadherence

(21) .

The introduction of clozapine served as an impetus to develop other compounds with the “atypical” characteristic of a lower propensity to cause movement disorders. In general, the second-generation antipsychotics are less likely than first-generation antipsychotics to produce extrapyramidal symptoms

(27,

28) . Although low dosages (less than 600 mg chlorpromazine-equivalents) of the low-potency conventional antipsychotics are an exception to this generalization, the second-generation medications have been shown to have superior efficacy to low-dose, low-potency conventional antipsychotics

(8) . In the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) study

(29), no significant differences between antipsychotics were observed in rating scale scores for extrapyramidal symptoms, yet the rate of discontinuation because of extrapyramidal side effects was significantly higher among patients taking perphenazine, the only first-generation medication in the study, than among those taking second-generation medications. This finding suggests a notable disconnect between rating scale measures for movement disorders and the clinical impact of such disorders. Patients in the CATIE study who had a prior diagnosis of tardive dyskinesia were also excluded from the perphenazine arm, diluting the impact of movement side effects from first-generation antipsychotics in the study. Furthermore, it is likely that CATIE raters were not sensitive to milder manifestations of akathisia and other movement disorder syndromes

(30), which would also have reduced measured differences among medications in extrapyramidal side effects.

In general, the second-generation antipsychotics produce lower rates of akathisia compared with haloperidol even when low dosages of haloperidol are used

(31 –

37) . Differences among the second-generation medications, however, are neither clear nor consistent. The CATIE investigators

(29) reported similar rates of akathisia in phase 1 among the second-generation antipsychotics (ranging from 5% to 9%). Aside from the CATIE trial, there is a paucity of data regarding the relative risk of akathisia among the second-generation antipsychotics.

Tardive dyskinesia was first observed shortly after the introduction of chlorpromazine. With conventional antipsychotics, the incidence of tardive dyskinesia is generally reported to be 5% per year, at least for the first 5 years of treatment

(38) . The incidence with second-generation antipsychotics appears to be significantly lower, approximately 1% per year on average

(39) ; however, the available studies are limited by methodological problems and relatively brief follow-up periods.

Tardive akathisia, unlike tardive dyskinesia, has not been widely studied or universally accepted. Second-generation antipsychotics are probably less likely than the first-generation antipsychotics to produce tardive akathisia, but no systematic data are currently available.

Assessment of Akathisia and Other Movement Disorders

Although the introduction of the second-generation antipsychotics has decreased the prevalence and severity of neurological side effects in patients treated with antipsychotics, acute and chronic extrapyramidal side effects remain relatively common. For some individuals, these symptoms can constitute a substantial symptom burden that can be difficult to detect. This is particularly true for restlessness, which, as mentioned above, can be difficult to discriminate from agitation or anxiety. We recommend examining patients for acute, chronic, and tardive akathisia as a component of a regular evaluation of extrapyramidal symptoms. The Mount Sinai guidelines on the pharmacotherapy of schizophrenia

(40) recommend a relatively complete examination for extrapyramidal symptoms and tardive dyskinesia before a patient is started on a new medication, and then every 6 months for patients who receive a first-generation antipsychotic and every 12 months for those receiving a second-generation antipsychotic. The guidelines recommend more frequent monitoring for individuals at high risk, such as elderly patients.

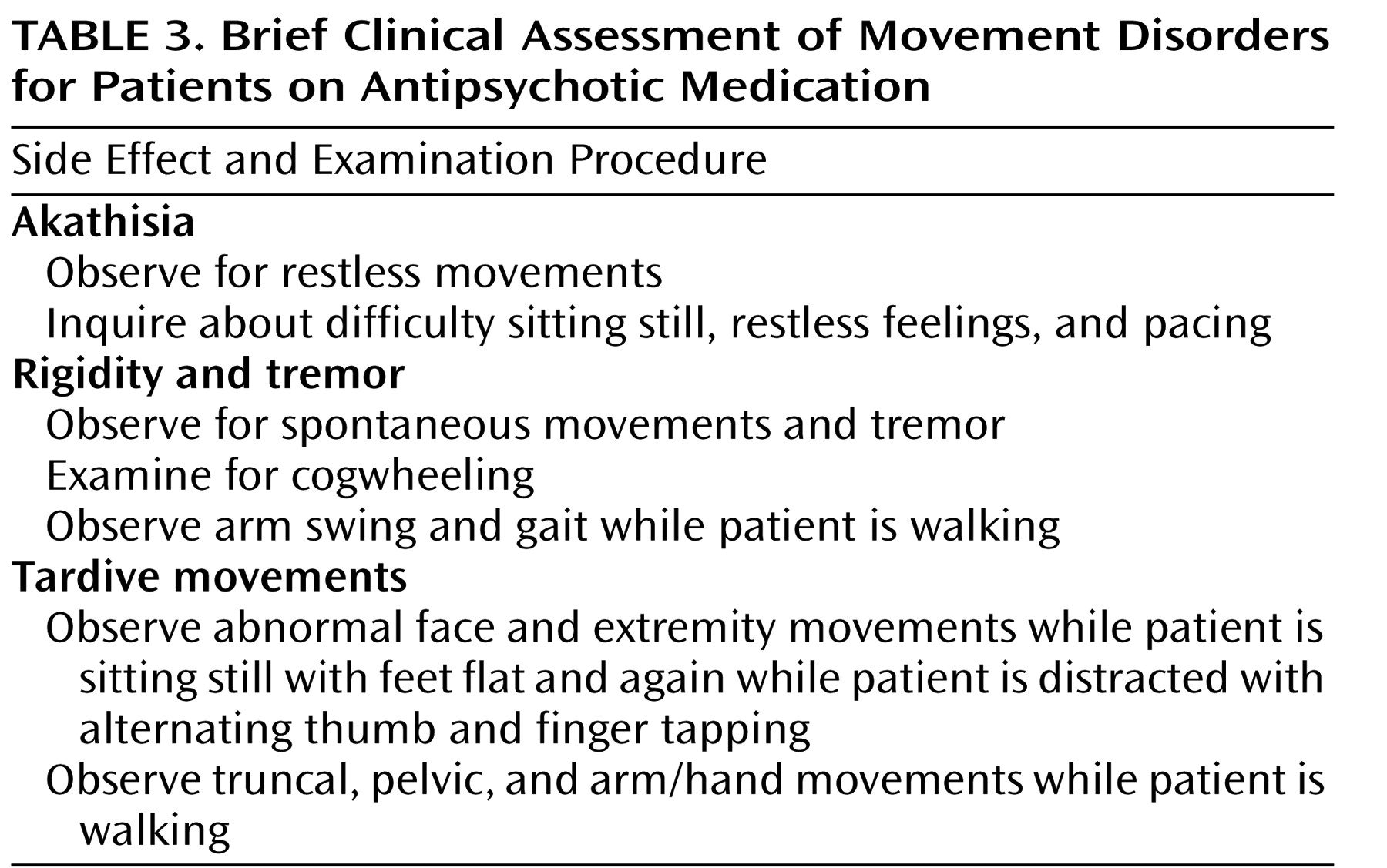

The Mount Sinai guidelines represent a minimal level of monitoring. More frequent monitoring that focuses on the most common side effects may be appropriate during acute treatment, during periods of dosage adjustment, and when there is concern about specific side effects. In many clinical settings, heavy case loads may make it difficult for clinicians to administer a complete examination for extrapyramidal symptoms and abnormal involuntary movements. In such circumstances, we recommend a relatively brief examination that can be administered in less than 3 minutes (

Table 3 ). Since the goal of this examination is to detect mild movements, we are not recommending any system for rating. If abnormal movements are detected, we recommend systematic rating with descriptions of the symptoms.

Management of Akathisia

Relatively little information is available to guide clinicians in treating chronic or tardive akathisia

(41 –

43) . Case reports (reviewed in reference 14) and small randomized studies

(44 –

54) suggest that benzodiazepines, propranolol, and anticholinergics may be of some help in treating acute akathisia. We recommend trials of propranolol, anticholinergics, or benzodiazepines for reducing the immediate distress that patients experience from restlessness. In our experience, these treatments, which are already often inadequate for treating acute akathisia

(41 –

43), are even less effective in chronic akathisia.

If it is feasible to reduce the antipsychotic dosage, this should be done gradually. Changing the patient to an antipsychotic with a lower liability for extrapyramidal side effects—particularly clozapine—is supported by our clinical experience and by small randomized trials

(55,

56) and case series

(57,

58) . It is important to inform patients that there may be a delay of weeks or months from the time the antipsychotic regimen is changed until the patient experiences substantial relief.

Summary and Recommendations

Restlessness is a relatively common complaint in patients receiving antipsychotic medications. Possible causes include agitation, anxiety, and akathisia. It is important to bear in mind that the subjective experience of restlessness will not always lead to obvious increases in motor behavior. We recommend that clinicians regularly assess both subjective and objective restlessness. If restlessness is a result of akathisia, clinicians should assess whether it is acute or chronic. The differentiation can be made by considering the time of onset of the symptom as well as the response of the akathisia to changes in antipsychotic dosage.

If the diagnosis is chronic or tardive akathisia, we recommend trials of an anticholinergic, a central-acting beta-blocker, or a benzodiazepine to relieve the patient’s distress. At the same time, clinicians should consider changing the patient’s antipsychotic pharmacotherapy. Alternatives to be considered are lowering the dosage of antipsychotic, changing to a less potent second-generation antipsychotic, or changing to clozapine.

When Mr. B, from the clinical vignette, was transferred to the schizophrenia clinic, he was on a combination of 10 mg of olanzapine at bedtime, 2.5 mg of clonazepam three times a day, 0.5 mg of lorazepam once a day, 5 mg of trihexyphenidyl once a day, 2 mg of benztropine once a day, 20 mg of propranolol three times a day, and 25 mg of atenolol once a day. Akathisia was his primary complaint, despite the multiple medications aimed at ameliorating the restlessness. He denied active psychotic symptoms. The goal of treatment with Mr. B was to find a regimen that would allow adequate treatment of his schizophrenia while minimizing his movement disorder side effect.

Over the next 8 years, Mr. B had trials of up to 850 mg/day quetiapine, up to 60 mg of ziprasidone twice a day, up to 15 mg/day of aripiprazole, and combination treatments (usually due to prolonged cross-titration schedules) of olanzapine with quetiapine, ziprasidone with quetiapine, and aripiprazole with quetiapine. With each initial medication change or dosage increase, Mr. B would report an improvement in his akathisia, but the restlessness quickly returned; the symptoms were at their worst when he was on aripiprazole and ziprasidone. He was also restarted several times on lorazepam and propranolol, but improvements on benzodiazepines and beta-blockers were equally short-lived, and typically these medications were discontinued after several weeks or months. The medication regimen was changed fairly frequently in an effort to balance worsening akathisia at higher dosages of antipsychotic medication and emerging psychotic symptoms of paranoia, thought disorder, and anxiety at lower dosages. Although the presumptive diagnosis was tardive akathisia, based on the chronicity and the noted improvement on increasing antipsychotic dosage or switching medications, Mr. B was never off antipsychotic medications.

For many such patients, clozapine is the only effective strategy. In 2005, Mr. B was started on clozapine specifically to target the tardive akathisia. His dosage was titrated to 100 mg in the morning and 200 mg at bedtime, and it has remained stable since. Mr. B has not needed adjunctive antipsychotic medications, benzodiazepines, or beta-blockers for akathisia symptoms while on this regimen. He does still have symptoms of restlessness, but the symptoms are markedly better than they were prior to treatment with clozapine. Both Mr. B and his mother report that the akathisia, while still bothersome, is tolerable and manageable at this level.