Panic disorder involves two cardinal features: panic attacks, defined as acute surges of fear

(1), and anticipatory anxiety

(2), defined as persistent apprehension about future panic attacks

(3) . Only a subset of the many individuals who experience panic attacks develop panic disorder. The transition from panic attacks to panic disorder is thought to involve a process whereby anxiety in anticipation of subsequent panic attacks

(4) increases the likelihood of additional attacks

(5) and leads to full-blown panic disorder

(3) . According to this assessment, marked anticipatory anxiety about the uncertain recurrence of panic attacks leads to chronic anxiety

(2) .

Interestingly, most research on the physiology of panic disorder focuses specifically on panic attacks as opposed to anticipatory anxiety in panic disorder. Understanding the correlates of anticipatory anxiety in the disorder may be very important. Because panic attacks typically are irregular and uncertain

(2) and are perceived as arising “out of the blue,” heightened sensitivity to unpredictable aversive events among individuals who experience spontaneous panic attacks may, over time, lead to persistent anticipatory anxiety, facilitating the transition from panic attacks to full-blown panic disorder. Consistent with this prediction, the absence of predictability is a key variable in the origin and maintenance of chronic anxiety states

(6 –

8), both in human and animal models

(8,

9) .

Previous studies have generated mixed evidence concerning sensitivity to unpredictability in panic disorder. For example, some studies have shown that providing specific and detailed information about the effects of a panicogenic challenge reduces susceptibility to panic in the disorder

(11), whereas other findings have demonstrated no such effects

(11,

12) . Nevertheless, these findings remain of unclear relevance to research on temporal predictability in animal models of anxiety, i.e., these studies relied on paradigms relatively far removed from models used with rodents. Somewhat surprisingly, in studies that used a more translational approach with humans, we

(13) as well as other investigators

(14) found that patients with panic disorder displayed normal fear, as indexed by fear-potentiated startle, when anticipating predictable threat. The present study tests the hypothesis that panic disorder involves abnormal response specific to unpredictable threat, despite normal response to predictable threat. We tested this hypothesis using a well-validated startle paradigm

(15) . Anxiety was assessed across the following three conditions: 1) a predictable condition in which unpleasant events could occur only during a discrete “threat” cue, 2) an unpredictable condition during which unpleasant events could occur at any time, and 3) a neutral condition during which no unpleasant event was delivered. We hypothesized that panic disorder would be associated with normal startle in response to threat (predictable) cues but enhanced startle in response to unpredictable contexts.

Discussion

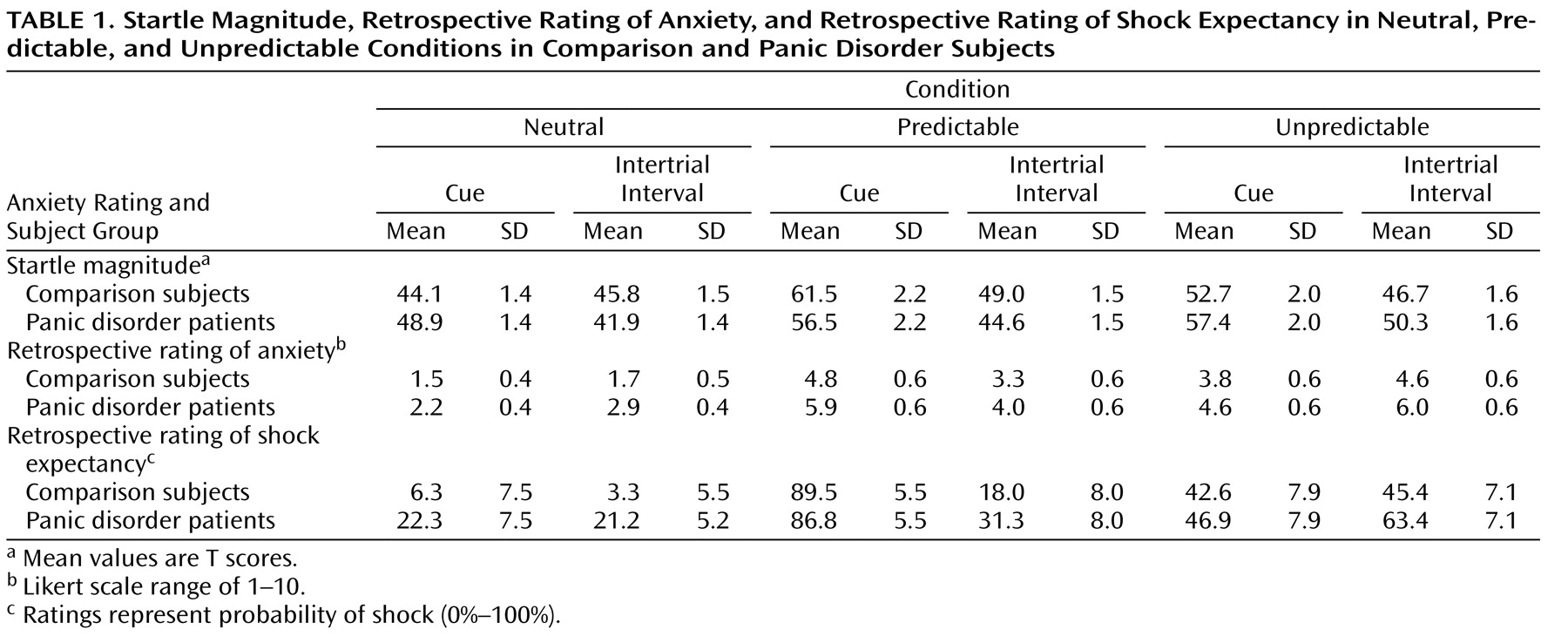

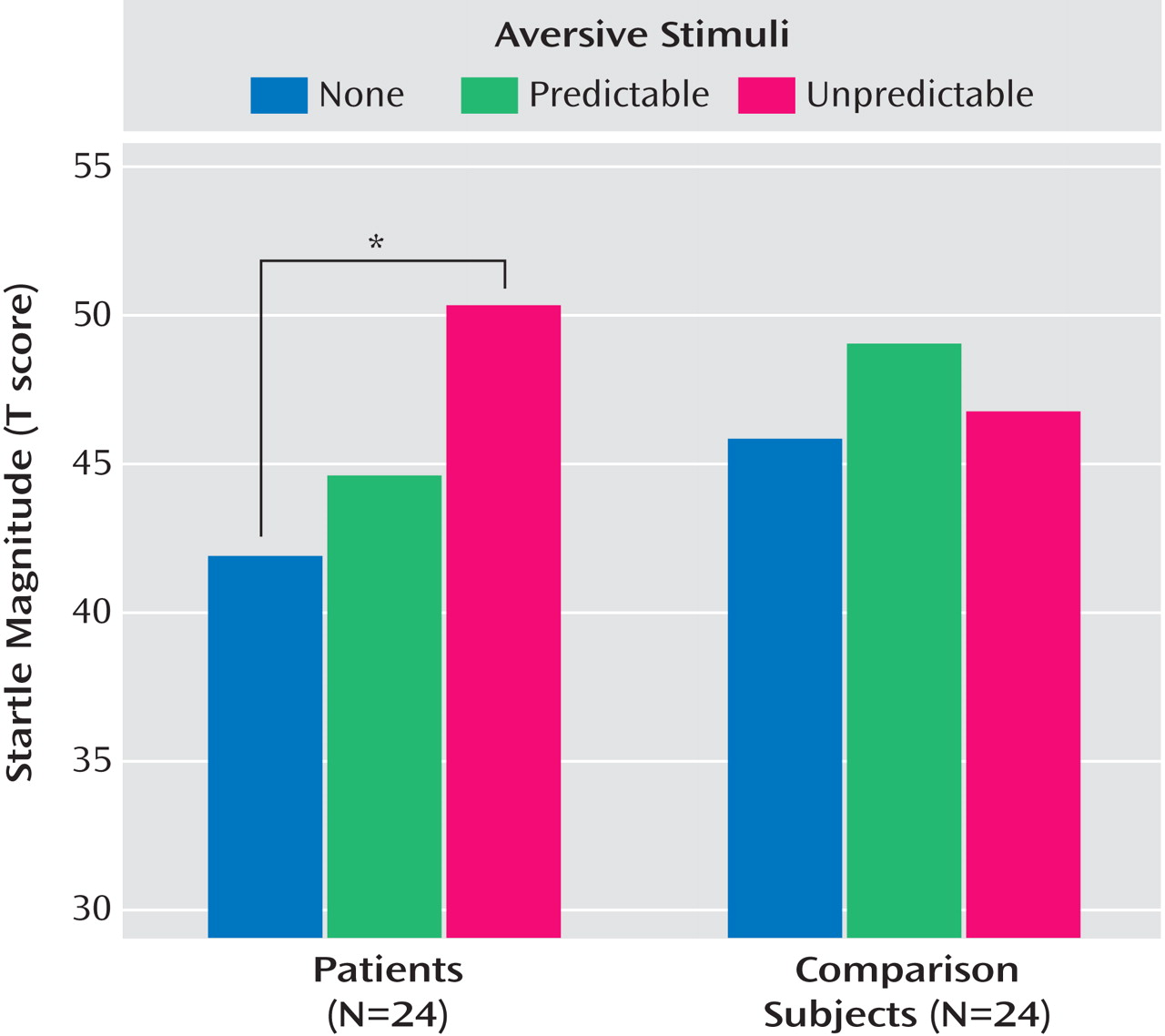

As predicted, patients with panic disorder exhibited greater anxiety in the unpredictable condition relative to healthy comparison subjects. Startle was substantially potentiated by the threat cue signaling an aversive event, but the magnitude of this effect did not vary by diagnosis. In contrast, startle in the context of the unpredictable condition differentiated patients with panic disorder from healthy comparison subjects, reflecting increased anxiety from the neutral to the unpredictable conditions in patients but not comparison subjects.

Both the large fear-potentiated startle response to the threat cue

(15,

20,

21) and the similar degree of potentiation across groups replicate previous findings

(13,

14) . Contrary to recent suggestions

(14), symptoms of depression did not appear to mask elevated fear-potentiated startle in panic disorder patients. Subclinical symptoms on the Beck Depression Inventory did not predict startle.

While anxious anticipation of signaled aversive stimuli did not differentiate among comparison subjects and patients, unsignaled presentations of the same stimuli elicited robust anxiety response only in patients. Specifically, startle in the unpredictable condition during the cue-free period provides a measure of persistent anxiety to the experimental context. This measure was significantly potentiated relative to the neutral condition in the panic disorder but not healthy comparison group. The absence of startle potentiation to the unpredictable condition in healthy subjects replicates prior reports

(15,

22) . Interestingly, prior reports have also suggested that more aversive stimuli (e.g., shock) than those used in the the present study do potentiate startle to the unpredictable condition

(15) . The results of these studies indicate that in healthy participants, unpredictability increases anxiety only when sufficiently aversive stimuli are used. The finding that less aversive stimuli are sufficient to elicit startle potentiation in the unpredictable condition among patients with panic disorder raises the possibility that the threshold for anxious responding to aversive stimuli was lower in patients relative to comparison subjects. This is unlikely because one would have expected panic disorder patients to also display greater fear-potentiated startle to signaled threat relative to healthy comparison subjects. The alternative and more probable explanation is that the panic disorder patients were abnormally sensitive to unpredictability. Predictability is a key factor in various experimental models of anxiety

(6 –

8,

23) . In panic disorder, anticipation of unpredictable and irregular panic attacks may contribute to the etiology and maintenance of chronic anxiety and subsequent avoidance by causing high levels of persistent anxious apprehension about the recurrence of panic attacks

(2,

24) which in turn, may increase the likelihood of panic attacks

(5) . This is consistent with theories that posit a causal relationship between panic attacks and interpanic anxiety and agoraphobia

(2) .

The present study documents a proneness to react with enhanced anxiety to an unpredictable, nonspecific stressor. This raises the question of the link between unpredictability and panic disorder. One possibility is that panic disorder patients develop a persistent fear of unpredictable danger following repeated uncued panic attacks and any aversive stimulus can generate physiological arousal that can be misinterpreted as the onset of a panic attack. According to this view, vulnerability to unpredictability is an acquired deficit that may contribute to the maintenance and worsening of panic disorder because it enhances anticipatory anxiety, which can promote panic symptoms

(5) . Alternatively, heightened sensitivity to unpredictable aversive events may be a pre-existing vulnerability factor for panic disorder. Consistent with this view, a recent study found that nonaffected children and adolescents of parents with panic disorder exhibit increased anticipatory anxiety during a 10-minute period, during which they breathed room air via a breathing mask while waiting for an uncued panicogenic CO

2 challenge

(25) . At the same time, they showed normal responses to the acute challenge

(25) . Thus, unpredictable stressors experienced by at-risk individuals may elicit persistent anxiety symptoms that, following the first uncued panic attacks, trigger attacks with increasing frequency over time through a progressive sensitization process. For example, in rodents, unpredictable shocks increase noradrenergic activity in various brain areas involved in fear responses such as the amygdala, hypothalamus, thalamus, and locus coeruleus

(26) . Sensitization of regions such as the locus coeruleus over time may lead to a hyper-reactive fear or alarm response to mild stressors, which could escalate into a panic attack. This interpretation is consistent with findings pointing to noradrenergic dysregulation in panic disorder

(27,

28) .

The present findings are consistent with animal data suggesting a system model of anxiety in which phasic fear to discrete threat cues and sustained aversive anxiety to unpredictable danger represent functionally distinct states mediated by different structures

(29) . Walker et al. have convincingly shown that the amygdala and the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis are involved in short- and long-duration aversive responses, respectively

(10) . Other investigators, using measures other than the startle reflex, have confirmed the role of the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis in sustained aversive states

(30 –

34) . We recently reported that the benzodiazepine alprazolam reduced context-potentiated startle to unpredictable shocks without affecting fear-potentiated startle to a threat cue

(20) . The present findings of heightened anxiety among panic disorder patients exclusively to unpredictable aversive events are consistent with these observations. The fact that this abnormally elevated response in panic disorder is also alleviated by alprazolam, a drug used to treat anticipatory anxiety, when tested in healthy subjects gives validation to our experimental model.

This study must be considered in light of several limitations. Subjective anxiety and expectancy rating reports did not replicate the startle data. Similar dissociation between self-reports and physiology

(21,

35,

36) are frequently reported. One complicating factor in the current study pertains to the fact that startle was used to probe anxiety online, whereas subjective anxiety measures were retrospectively assessed, possibly obscuring group differences. We chose to only assess anxiety retrospectively for concerns that online assessment may have influenced group differences through demand features. Alternatively, startle and subjective ratings may reflect distinct aspects of anxiety, with startle assessing primitive-defensive-reflex systems and verbal report assessing elaborative cognitive systems. It is nevertheless noteworthy that the patients overestimated the probability of receiving an aversive event in the cue-free periods compared to the comparison subjects. This is consistent both with prior clinical research on the prediction of panic-attack probability

(37) and with prior theory on panic disorder pathophysiology

(38) . Finally, it is unclear whether vulnerability to unpredictability is specific to panic disorder. Unpredictability may also play a role in anxiety disorders characterized by persistent signs of anticipatory anxiety, including generalized anxiety disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

(6 –

8) . It is possible that unpredictability plays less of a role in disorders associated with clearly identifiable stressors (e.g., phobias) than in anxiety disorders characterized by generalized, high, negative affect (panic disorder, PTSD, generalized anxiety disorder)

(39) .

The present study found increased anxiety to unpredictable aversive events in panic disorder. This vulnerability may be a premorbid risk factor for panic disorder, or it may contribute to the maintenance and exacerbation of panic symptoms. Longitudinal studies in individuals at risk for panic disorder will help to clarify the role this deficit plays in panic disorder. These findings may also implicate brain structures relevant to panic disorder given evidence pointing to distinct neural systems mediating short- and long-duration anxious responses

(10) . Using functional magnetic resonance imaging, we have identified a separate network of neural structures during anticipation of predictable and unpredictable aversive stimuli

(40) . The bed nucleus of the stria terminalis was not a part of these neural networks, but this is likely a result of current limitations of brain imaging techniques, which do not have the spatial resolution to unambiguously detect activation of this structure

(41) . Nevertheless, the current experimental paradigm represents a valuable tool with which to study panic disorder in the laboratory setting and, as such, will likely facilitate future efforts to elucidate the neurobiology of the disorder.