Early-onset conduct problems predict both psychiatric and physical health problems in adult life

(1,

2) . Conduct problems that manifest early in life are also thought to reflect biological vulnerability to antisocial behavior

(3) . Recent studies have highlighted the finding that within this early-onset group, callous-unemotional traits index a particularly serious form of conduct disturbance. Callous-unemotional traits include such characteristics as lack of guilt and empathy, which are also considered primary in clinical descriptions of adult psychopathy

(4) . Recent data from studies of twins suggest that conduct problems in callous-unemotional children are under strong genetic influence

(5,

6) .

Both adult psychopaths and children with conduct problems and callous-unemotional traits have difficulty processing visual and auditory displays of fear and sadness

(7 –

9) . Both groups also experience difficulties in aversive learning paradigms

(8) . This profile is also seen in neuropsychological patients with damage to the amygdala, one of the brain’s key affect-processing structures

(10) . Consequently, it has been proposed that the difficulties in affective processing seen in adult psychopaths and children with conduct problems and callous-unemotional traits are accompanied by amygdala impairment

(8) . Early amygdala dysfunction may have a negative impact on the development of empathy

(8) .

Functional brain imaging data from studies of healthy adults and children support the amygdala’s role in processing emotional facial expressions and other affective stimuli

(11 –

13) . To date, there have been a handful of functional brain imaging studies of adult psychopathy and one study of adolescents with conduct problems and callous-unemotional traits. All implicate reduced amygdala reactivity in individuals with psychopathy or elevated levels of psychopathic personality traits as compared with both healthy and institutionalized comparison subjects, although the laterality of the reported difference varies among studies, probably reflecting the paradigm used

(14 –

18) . Amygdala hyporeactivity has been suggested to be associated with the emotional dysfunction observed in psychopathy

(8) .

Studies of healthy adults suggest a role for the rostral anterior cingulate cortex in extinguishing amygdala reactivity during emotional arousal

(19,

20) . The amygdala hypoactivity observed in adults with psychopathy could thus reflect down-regulation of amygdala activity by the anterior cingulate cortex. Aside from the finding of amygdala hypoactivity in psychopathy, the rostral anterior cingulate cortex has been implicated in more than one brain imaging study of psychopathy

(14,

15) . In each case, adults with psychopathy showed less rostral anterior cingulate cortex reactivity than comparison subjects. This finding suggests that the reduced amygdala reactivity in adults with psychopathy might not, in this case, be due to increased emotional regulation by the anterior cingulate cortex.

Despite a prominent model of psychopathy proposing that it is a developmental disorder of early amygdala dysfunction, to date, only one neuroimaging study of adolescents with conduct problems and callous-unemotional traits has been published

(18) . The study reported amygdala hyporeactivity to fearful faces in adolescents with conduct problems and callous-unemotional traits relative to comparison subjects and adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. We also know of one functional MRI (fMRI) study of emotion processing in adolescents with conduct disorder, which demonstrated reduced left amygdala and right dorsal anterior cingulate cortex activation to nonfacial emotional stimuli in adolescents with conduct disorder relative to healthy comparison subjects after co-occurring anxiety and depression symptoms were controlled for

(21) . Structural MRI data from the same group indicated reduced left amygdala volume in adolescents with conduct disorder

(22) .

Given that lack of anxiety is thought to be a core characteristic of psychopathy

(23), it is possible to infer from the findings of the previous fMRI study of adolescents with conduct disorder

(21) a hypothesis that children with callous-unemotional traits and conduct problems may show reduced amygdala reactivity. This hypothesis was supported by the recent study of adolescents by Marsh et al.

(18) . Behavioral genetic findings of increased genetic vulnerability to antisocial behavior in children with conduct problems and callous-unemotional traits

(5,

6), as well as previous behavioral studies

(7 –

9), further underscore the importance of studying the brain reactivity to emotional stimuli in this group.

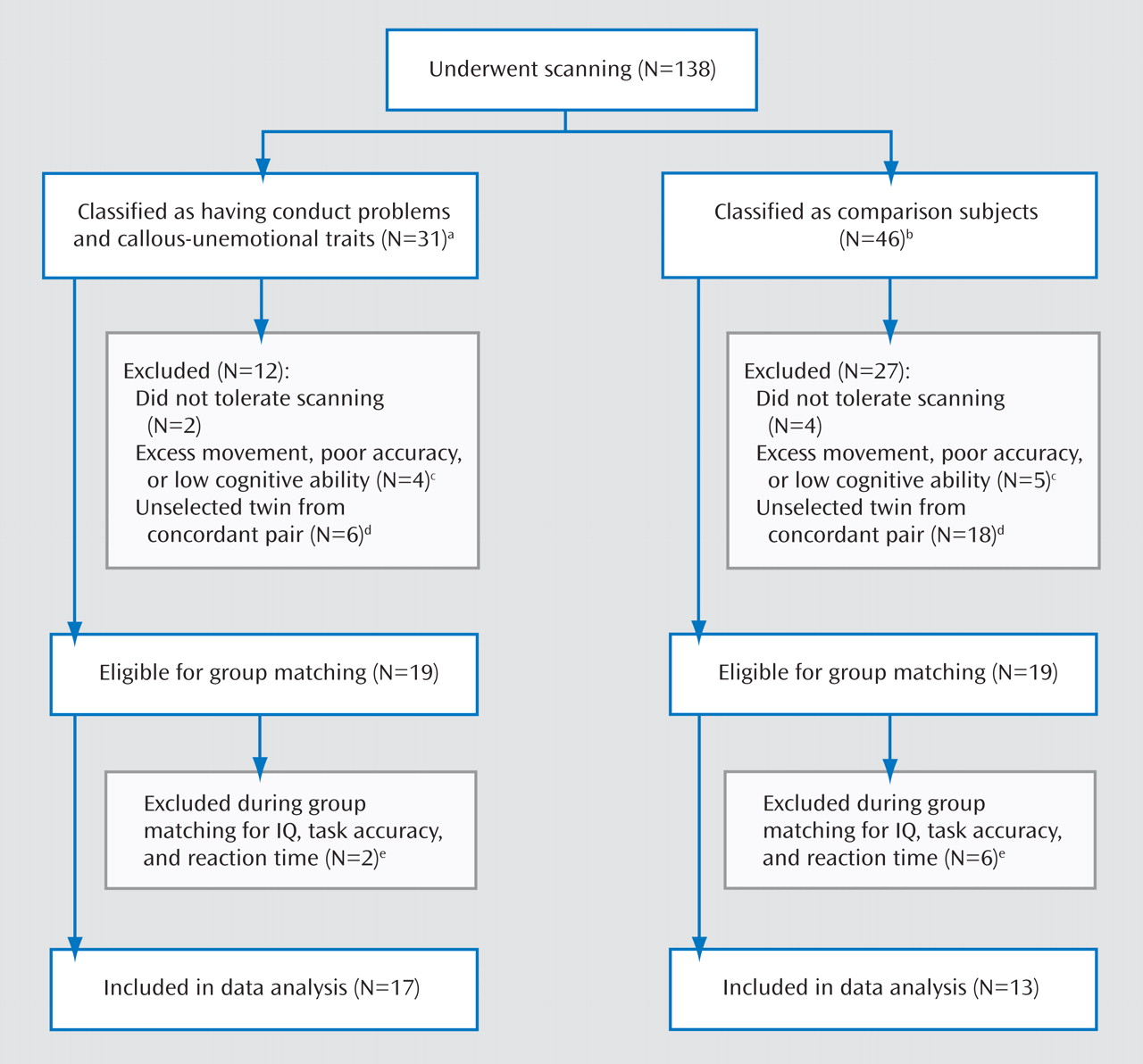

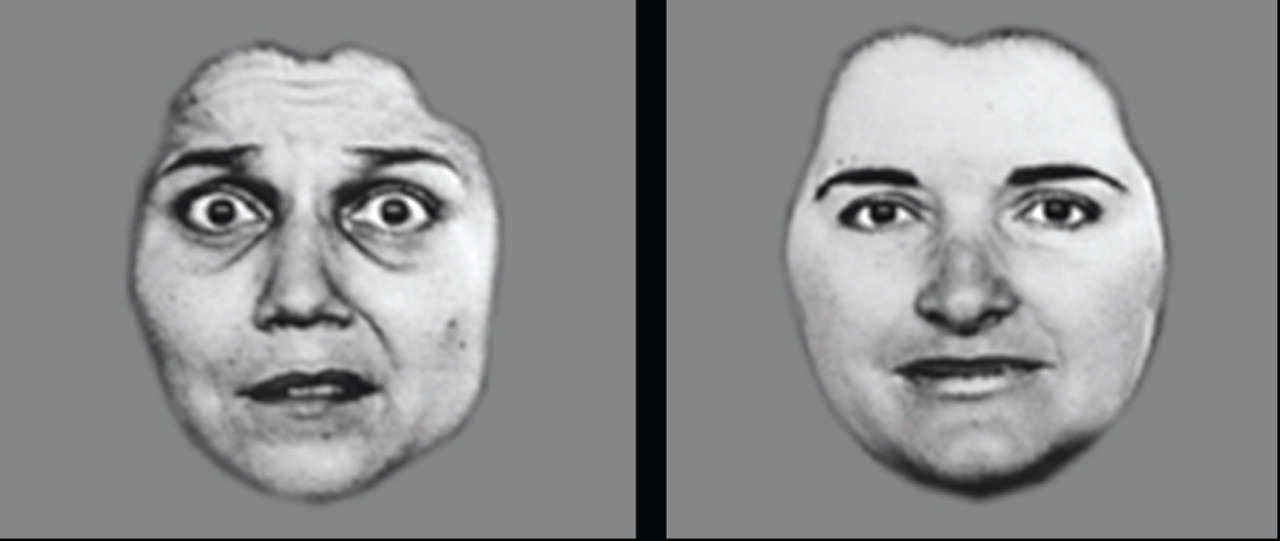

The task used in this study was designed to investigate amygdala reactivity to fearful faces. In previous studies, this and similar tasks employing fearful facial stimuli have been shown to reliably elicit activation of the amygdala in healthy adults

(12) and children

(11,

13) . Our primary goal was to examine differences in amygdala reactivity to fearful faces between boys with conduct problems and elevated levels of callous-unemotional traits and an age- and IQ-matched comparison group. We hypothesized that boys with conduct problems and elevated levels of callous-unemotional traits would show decreased amygdala reactivity to fearful faces relative to the comparison subjects. We further hypothesized that this decreased amygdala reactivity would not be associated with stronger anterior cingulate cortex reactivity in this group, although, in line with adult data, it is possible that children with conduct problems and callous-unemotional traits may show reduced anterior cingulate cortex reactivity.

Discussion

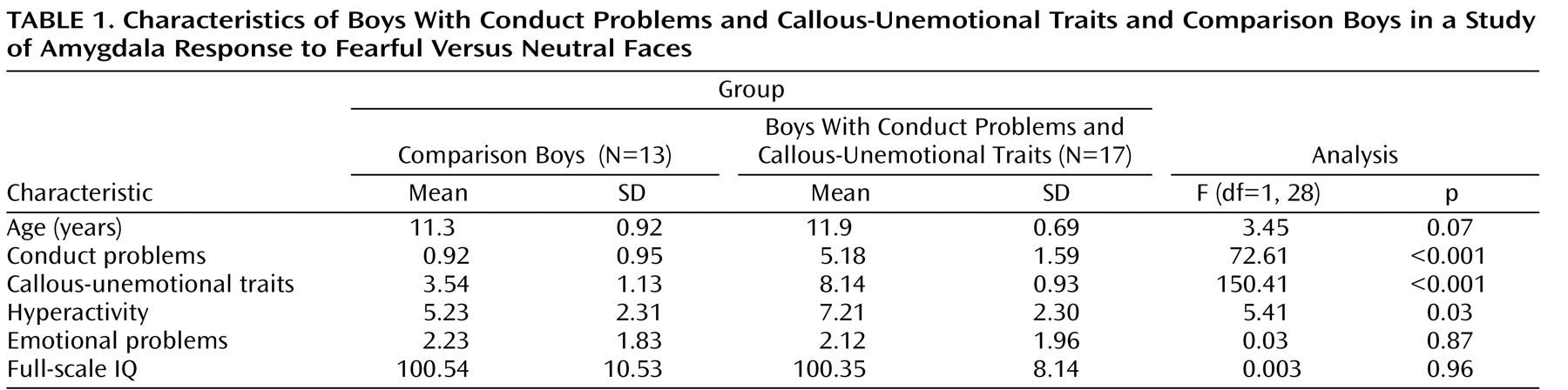

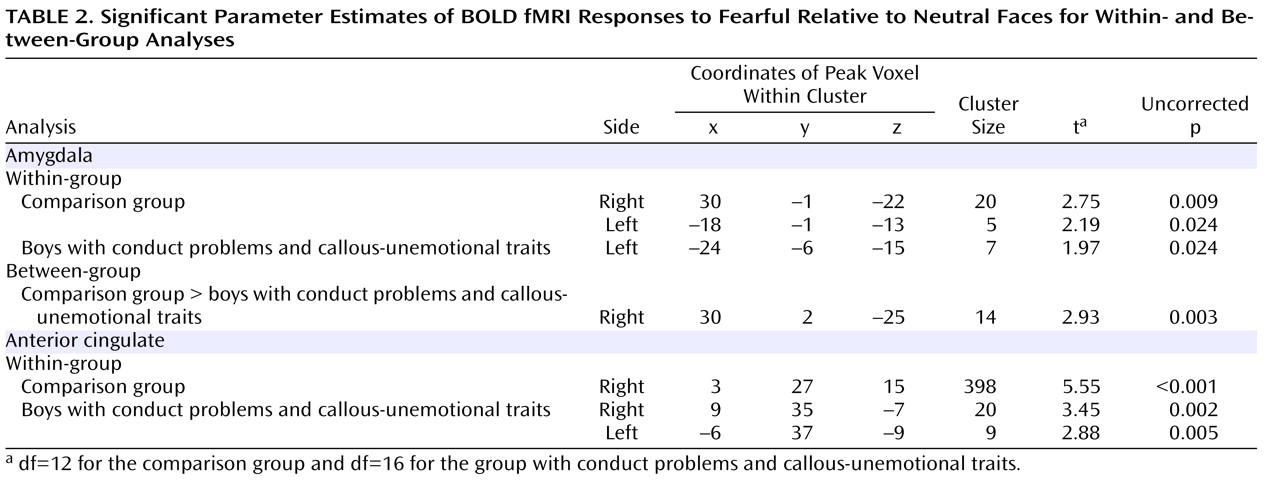

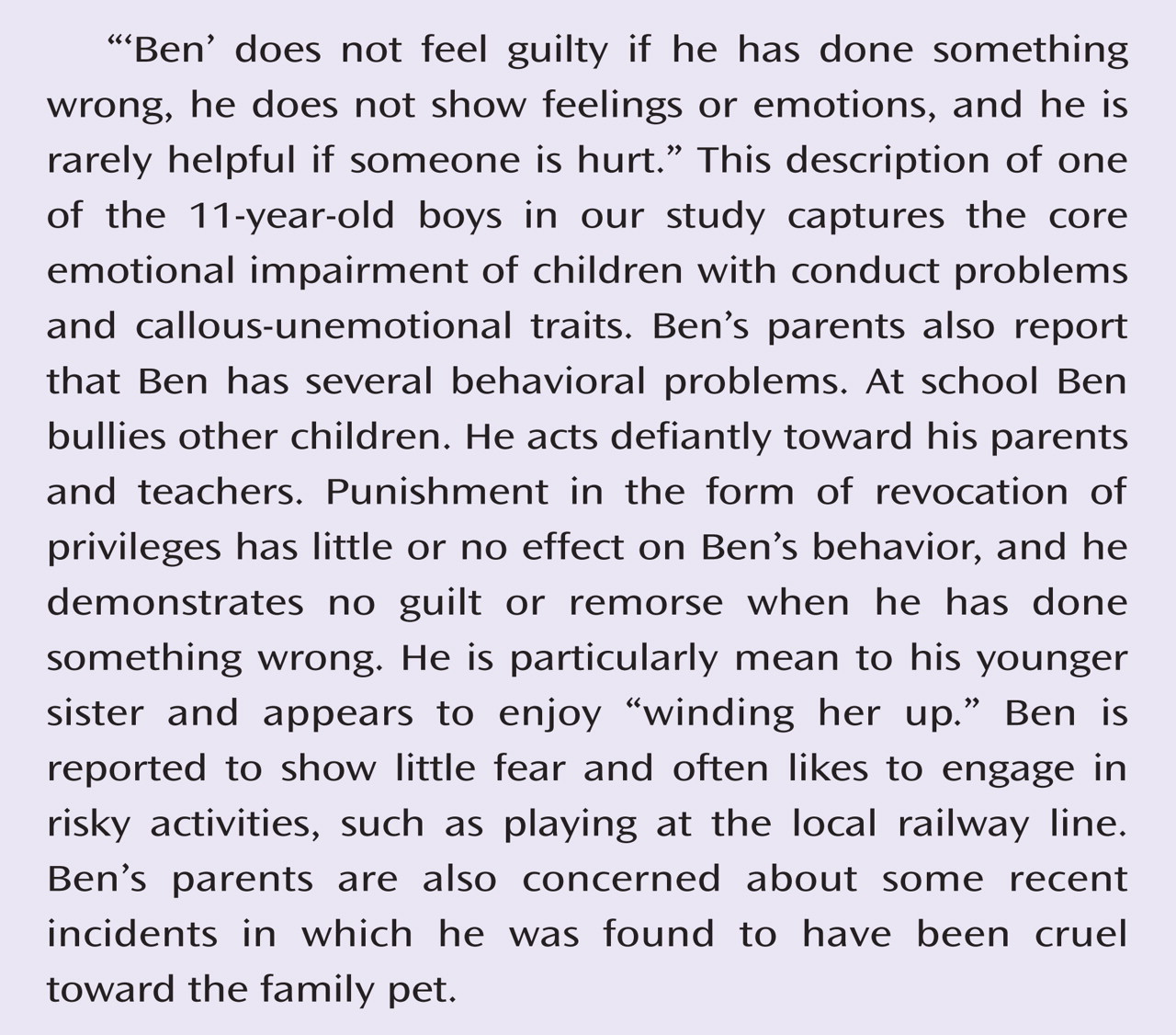

The results of this study are consistent with previous child and adult data suggesting that the amygdala typically activates more strongly to fearful faces than to neutral faces

(12,

13) . These data confirm previous child brain imaging findings

(11,

13) and indicate that amygdala involvement in the processing of emotional facial stimuli has already developed by middle childhood. In our comparison group, both the right and left amygdala were activated significantly more to fearful faces than to neutral expressions. Boys with conduct problems and callous-unemotional traits showed only left-sided amygdala activation to fearful faces as compared with neutral expressions. When the two groups were compared, the boys with conduct problems and callous-unemotional traits thus showed relatively decreased amygdala reactivity to fearful facial stimuli in the right amygdala. Our data suggest that the emotional impairment evident in children with conduct problems and callous-unemotional traits is accompanied by reduced right-sided amygdala reactivity to others’ fear. Both groups showed statistically significant reactivity in the anterior cingulate cortex region of interest, but there were no statistically significant group differences. Crucially, the reduced amygdala activation in boys with conduct problems and callous-unemotional traits was not associated with stronger anterior cingulate cortex reactivity.

Frick and Marsee have highlighted the importance of charting psychopathic personality markers (callous and unemotional traits) in childhood

(4) . The Antisocial Process Screening Device we used to assess callous-unemotional traits in this study was designed to extend assessment of psychopathic traits to children, with the view that the callous and unemotional traits mark one important risk factor for lifelong persistent antisocial behavior. Callous and unemotional traits include such characteristics as lack of guilt and empathy, which are also considered primary in clinical descriptions of adult psychopathy

(4) . Children with callous-unemotional traits show a specific behavioral and neurocognitive profile that is similar to that seen in adult psychopaths

(8) . At a behavioral level, conduct problems with elevated levels of callous-unemotional traits are associated with a poorer long-term outcome and greater severity of antisocial behavior as compared with children with conduct problems but without callous-unemotional traits

(4) . At the neurocognitive level, children with conduct problems and callous-unemotional traits appear to suffer from emotional dysfunction characterized by difficulty in processing fear and sadness, as well as deficits in reinforcement learning

(8,

18) . Data from our own group indicate that antisocial behavior in children with elevated levels of callous-unemotional traits is strongly heritable, suggesting that children who display these traits may be particularly vulnerable genetically to antisocial behavior

(5,

6) . This finding raises the possibility that psychopathy may be a developmental disorder with particular personality and neurocognitive markers that can be delineated successfully in children

(8) .

Our findings are in line with fMRI studies investigating emotion processing in adult psychopaths, adolescents with conduct disorder, and adolescents with conduct problems coupled with callous-unemotional traits

(14 –

18,

21) . Reduced amygdala activation in individuals with psychopathy has been demonstrated with various affective stimuli

(14 –

18), with reduced right amygdala activation previously reported for a face processing paradigm

(16,

18) . Our study offers a replication of Marsh and colleagues’

(18) finding of amygdala hyporeactivity in response to fearful facial expressions in adolescents with both conduct problems and callous-unemotional traits, and it extends the work of Sterzer et al.

(21), who did not assess these traits in their sample of adolescents with conduct disorder. Our focus on younger children adds to findings by Marsh et al.

(18) and others

(14 –

17) by providing evidence suggesting that amygdala hypoactivity associated with callous-unemotional conduct problems is already present in some pre-adolescent and early adolescent children and lends support to the notion that psychopathy may be a developmental disorder related to amygdala dysfunction

(8) .

Our findings are in line with earlier behavioral data demonstrating difficulties in recognition of fearful expressions in children with conduct problems and callous-unemotional traits

(7) . Of course it would be unethical to label children as “psychopaths,” but it is worth noting that vulnerability to psychopathy appears to be present from childhood and manifests in both detectable trait differences and associated neurocognitive differences.

It has been proposed that psychopathy may be genetic in origin, and there are preliminary data to support this notion

(5,

6,

8) . Genetic vulnerability may set the tone for an individual’s neural reactivity to emotional stimuli, which is likely to be further moderated by environmental factors

(33) . Current imaging genetic studies have focused on reactive, nonpsychopathic antisocial behavior

(20,

34,

35), but our own group and others are planning to extend these investigations to psychopathic/callous-unemotional antisocial behavior.

There are several limitations to this study. First, we cannot exclude the possibility that with larger sample sizes, between-group differences might have emerged in additional brain areas. Second, the p values for our regions of interest were uncorrected for multiple comparisons. To increase our confidence in the findings, we reported data on only two regions of interest with empirical precedence (the amygdala and the anterior cingulate) and where cluster size exceeded five voxels. Third, the format of our task did not allow for the rest condition to be used as an additional baseline condition. Instead, neutral faces were used as the baseline condition. However, a 2×2 analysis of group by emotion may have provided more power to detect group differences. Fourth, we were not able to measure the gaze patterns of participants while they studied the stimuli in the scanner. Thus, although our behavioral data reveal no differences in accuracy or reaction time between the groups (and thus suggest that both groups were efficient in processing the stimuli), we do not know on which part of the face the participants fixated. Previous studies indicate that individuals with amygdala damage do not fixate on the most informative part of a fearful face, the eyes

(36) . Decreased gaze fixation to crucial aspects of emotional stimuli accounts for a moderate proportion of variance in amygdala activation in healthy adult females

(37) . Furthermore, overt fear recognition can be improved in children with callous-unemotional traits when they are asked to fixate on eyes in a face

(38) . It remains to be seen whether we could elicit stronger amygdala activation in children with conduct problems and callous-unemotional traits if they were to engage effortfully with processing the eyes in facial stimuli. Finally, our study did not include a group of children with conduct problems and no callous-unemotional traits. We hope to include such a group in future studies.