Differences Between Bereavement-Related Depression and Depression Related to Other Stressful Life Events

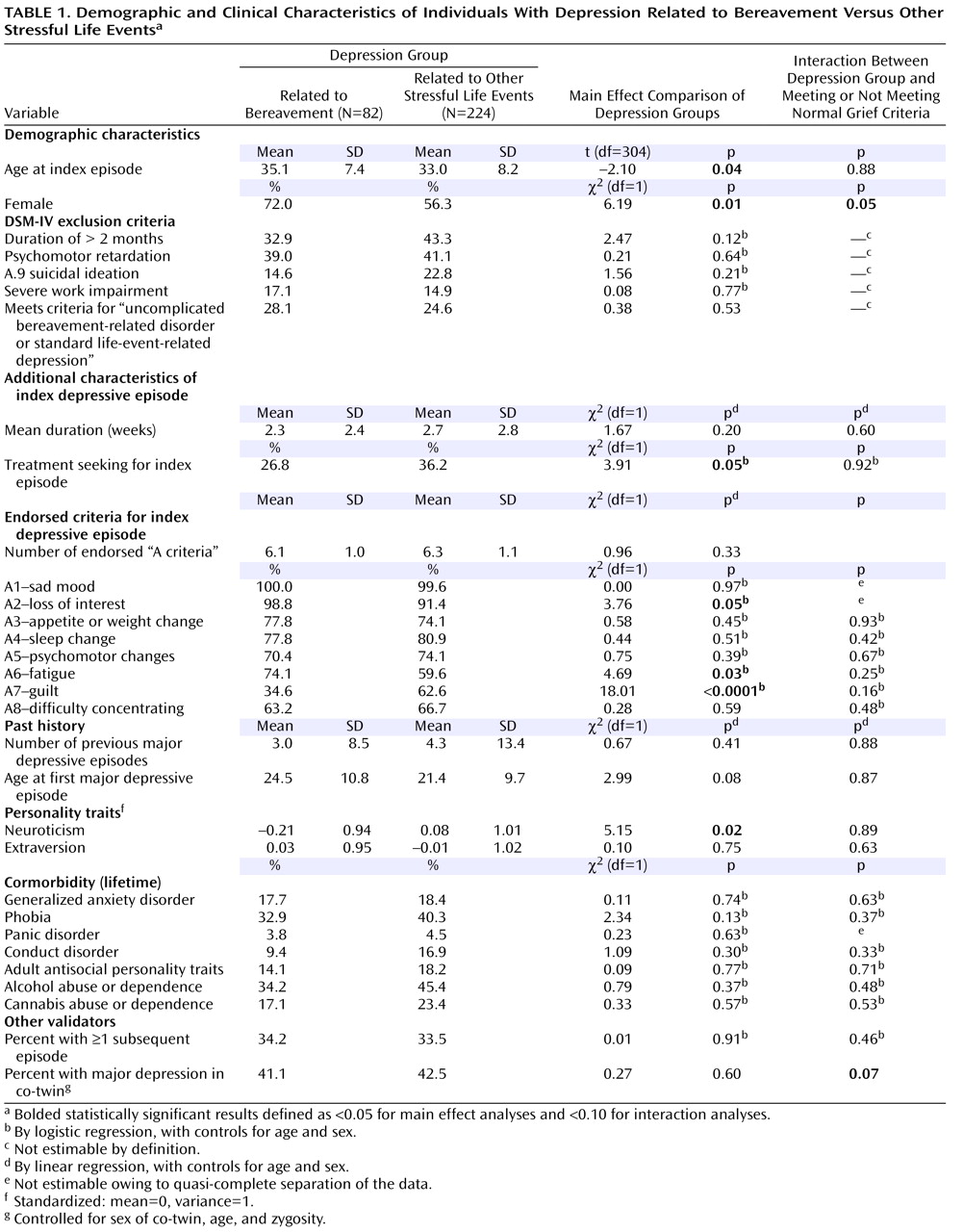

These analyses sought to evaluate the assumption implicit in DSM-III and subsequent DSM editions that bereavement-related depression is qualitatively different from depression related to other stressful life events. The two groups were similar in many important ways, including the duration of the index episode, the frequency of severe impairment, the clinical severity of the episode as reflected in the number of endorsed A criteria, the probability of endorsing six of the nine specific A criteria (including suicidal ideation and changes in appetite, sleep, and concentration), the number of prior depressive episodes, the age at onset of major depression, the pattern of comorbidity with a range of common internalizing and externalizing disorders, the risk for future depressive episodes, and the risk of major depression in their co-twin. Of interest, the symptomatic and duration criteria in DSM-IV for normal grief were met by an equal proportion of cases of bereavement-related depression and depression related to other stressful life events.

Despite these substantial similarities, bereavement-related depression and depression related to other stressful life events differed on seven potential validators. Subjects with bereavement-related depression were slightly older, more likely to be female, and less likely to seek treatment for the index episode, had lower levels of neuroticism, endorsed more frequently loss of interest and tiredness, and reported much less frequently symptoms of guilt. Given the number of tests performed (∼30), however, several of these positive results are likely to result from chance alone.

The older age of the subjects with bereavement-related depression is likely artifactual because the mean age of subjects reporting a “death event” in our entire sample (36.2, SD=9.0) was significantly higher than for those reporting divorce/separation, illness, and job loss (33.1, SD=9.0; t=13.69, df=6, 930, p<0.0001). We observed a female excess of subjects with bereavement-related depression. If bereavement-related depression arose solely as a result of the environmental stress of bereavement, the pattern of female preponderance in major depression

(12) might be reduced. A number of prior studies have observed similar proportions of men and women in bereavement-related depression

(13 –

16), while other studies reported a modest increase in the proportion of women with bereavement-related major depression

(17 –

20) .

The low percentage of individuals with bereavement-related depression who sought treatment is consistent with prior observations that those with the “depressions of widowhood” rarely perceived a need for treatment

(21) . This may reflect the widely shared conviction that bereaved individuals are “supposed” to be depressed, that such depressions are adaptive

(22) and self-limited, and that treatment is unnecessary if not unwise

(23) .

The findings with neuroticism are of particular interest because this personality trait is a good index of the genetic risk for major depression

(24 –

26) . These results suggest that individuals with bereavement-related depression have a lower level of genetic risk than those with depression related to other stressful life events and that their depressive episode arose largely as a result of their bereavement. However, this interpretation is not consistent with several other results. Such a hypothesis would predict that individuals with bereavement-related depression would have had fewer prior depressive episodes, and would have a lower risk of subsequent episodes, lower rates of comorbidity, and a lower risk for major depression in their co-twin. None of these predicted patterns was observed here or in our review of the prior literature

(27) . Overall, our results are not consistent with the hypothesis that bereavement-related depression is a more environmentally induced syndrome than depression related to other stressful life events.

Previous research with the VATSPSUD has demonstrated that different types of life events are related to different depressive symptom profiles

(28) . Thus, it is not surprising that three of nine “A criteria” for DSM-IV differed in rates of endorsement between the two groups. The increased rate of loss of interest in bereavement-related depression may be related to the effects of “withdrawal from ongoing life”—a core component of grief

(29) . Since sleep efficiency is impaired in grief, and especially so in grief complicated by major depression

(30), it is not surprising that bereavement-related depression is associated with considerable daytime fatigue. That guilt was observed in many more individuals with other stressful life events depression than bereavement-related depression may reflect the active role individuals perceive themselves playing in most life events, whereas the death of a loved one is typically removed from the bereaved’s locus of control. Indeed, we recently showed that when depressive symptoms occurred in relation to stressful events, guilt was most common after romantic breakups and least common after bereavement

(30) .

A low percentage of individuals with bereavement-related depression met criteria for symptoms and a course of illness consistent with “normal grief.” Strikingly, the same percentage of individuals with depression related to other stressful life events met these criteria. The depressive features that DSM tells us are characteristic of “normal grief” are as likely to be present in depression related to other stressful life events as in bereavement-related depression.

Comparison With Prior Studies

Our results can be usefully compared with those obtained in the most similar prior study

(20) . Using data on lifetime major depression from the National Comorbidity Survey, Wakefield et al. first identified subjects who reported a depressive episode in temporal proximity to bereavement and to other kinds of loss. Using DSM-III-R criteria for uncomplicated bereavement, they divided each group into an “uncomplicated” and “complicated” subgroup. They then compared these four groups on 18 indicators: 12 reflecting features of the index episode (number of depressive symptoms, presence of melancholic features, suicide attempt, and the presence of each of the 9A criteria) and six that describe aspects of their history of lifetime depression (duration of longest episode, ever interfered a lot, ever saw a professional, ever hospitalized, ever received medications, and number of recurrent episodes). Uncomplicated bereavement-triggered and other-loss triggered major depression significantly differed on only two of these 18 variables (higher rates of impairment and lower rates of suicidal ideation in the “other-loss” group). Although not a focus of their article, the authors presented results showing that the bereavement-triggered and other loss-triggered complicated subgroups were similar on seven of nine comparison variables for which they were examined, differing only in that the other loss-group had higher levels of recurrence and a less prolonged longest duration.

Although our results were similar to those obtained by Wakefield et al. in a broad sense—both reports found many more similarities than differences between bereavement-related depression and depression related to other stressful life events—our findings differed in a number of details. Given the many methodological differences between the two studies (e.g., different assessment instruments, and age distributions, lifetime versus last year sampling frames, partly overlapping sets of validators, and our ability to confirm the stressful event-major depression association that was not possible in the National Comorbidity Survey), it would be premature to try to explain all the differences as substantive.

Limitations

These results should be interpreted in the context of three potentially significant methodological limitations. First, the sample was restricted to white twins born in the Commonwealth of Virginia from 1934 to 1974. These results may not extrapolate to other groups, particularly older groups, in which bereavement events are particularly likely to occur. Second, because the null hypothesis can never be proven, the usefulness of our results are closely related to their statistical power. Despite our large sample of person-months, confirmed bereavement-related depression was an uncommon event. Using Cohen’s concept of small, medium, and large effect sizes

(31), our first set of analyses—the direct comparison of depression related to bereavement versus other stressful life events—had, for continuous measures such as personality or episode duration, approximately 97% power to detect medium and 34% power to detect small effects (

32, Table 2.3.5, N=120). We expect somewhat less power for tests of semicontinuous variables such as the number of prior or future depressive episodes. For the examination of categorical variables, such as prevalence rates of other disorders or risk of illness in co-twins, we can estimate that our comparisons have approximately 41% power to detect small effects and over 99% power to detect medium effects (

32, Table 7.3.15). Although we had reasonable power to detect all large and nearly all medium effect size differences between our groups of bereavement-related depression and depression related to other stressful life events, our sample sizes were generally insufficient to be able to detect most small effect size differences between these two groups. Our interaction analyses were undoubtedly less powerful and probably had power only to detect large effect sizes.

Third, by requiring cases of bereavement-related depression to be confirmed by the respondent, we underascertained episodes of bereavement-related depression in subject-years containing multiple episodes. We can, however, estimate the degree of underascertainment. In years with a single depressive episode, 71.4% of the suggestive subjects with bereavement-related depression were confirmed by the respondent while in years with multiple depressive episodes, only 27.5% of the suggestive episodes of bereavement-related depression were so confirmed. Assuming that the rate of confirmation in years with single episodes was the same as for years with multiple episodes, we identified ∼63% of all the bereavement-related depression (or 82 of an estimated 131 cases). Thus, the estimated risk for bereavement-related depression in our sample per person-month, corrected for underascertainment, is ∼0.049%.