Group Psychoeducation

Group psychoeducation (GPE) has been administered in two formats: alone (as adjunctive to medications) or as part of a larger systematic care intervention. The results differ accordingly. In a study conducted in Barcelona, Spain, Colom et al.

(12) randomly assigned 120 bipolar I and II patients to 9 months and 21 sessions of structured GPE or a 21-session unstructured support group. The structured GPE included lectures and exercises to enhance illness awareness, early detection and intervention with prodromal symptoms, medication compliance, and life style regularity, whereas the unstructured groups were supportive but not psychoeducational. Patients were free of comorbid disorders and had been in remission for at least 6 months. Over a 2-year study, the results strongly favored GPE: 67% of the GPE patients versus 90% of the unstructured group patients had recurrences. The effects extended to the number of days patients spent in the hospital, which may suggest that GPE facilitated early detection of manic episodes and a resulting decrease in their severity. Somewhat puzzling was the observation that patients were more likely to drop out of the structured groups (26.6%) than the unstructured groups (11.6%). Nonetheless, patients in GPE maintained higher lithium levels over the 2-year study.

The efficacy of GPE was also examined among bipolar adults with comorbid substance disorders

(13) . Bipolar I and II patients (N=62) were assigned randomly to 20 weeks of integrated group therapy or an equally intensive drug abuse counseling group. The integrated group focused on challenging cognitions relevant to the relapse and recovery processes of both disorders, whereas the drug counseling group focused on abstinence and coping with substance craving. Over 8 months, patients in the dual-focus groups had half as many days of alcohol use as those receiving only group drug counseling. The integrated groups did not prevent episodes of bipolar disorder; in fact, patients in the integrated groups had higher subsyndromal depression and mania scores than patients in the comparison group. The psychoeducation about mood disorders provided in the integrated groups may have increased the frequency with which patients recognized and reported mood symptoms.

Group Psychoeducation Within Systematic Care Models

Two studies have examined GPE within the context of overall systems of care. Working within 11 Veterans Administration (VA) settings, Bauer et al.

(14) administered a collaborative chronic care treatment consisting of evidence-based pharmacotherapy, a nurse care coordinator assigned to each patient to enhance adherence to treatment, regular telephone monitoring of prodromal mood symptoms, and a structured “life goals” program consisting of 5 weekly followed by twice monthly group sessions for up to 3 years. The GPE focused on relapse prevention strategies, medication adherence, and illness management. Patients in a treatment-as-usual group received usual VA care, which included medication sessions and occasional psychotherapy.

The study contained 306 bipolar I patients, 87% of whom began as inpatients. Over 3 years, patients in the collaborative care intervention had 6.2 fewer weeks in affective episodes, 4.5 weeks of which were attributable to reductions in the length of manic episodes. There were no differences between the collaborative care and the treatment-as-usual groups in the length of depressive episodes. Broad effects of the care intervention were found on social and work functioning, quality of life, and treatment satisfaction. Of interest, the group differences were not statistically reliable until 2 years, suggesting a delayed effect of psychoeducation and facilitated collaboration with care providers.

A study with a nearly identical design—and the largest psychosocial study to date—was carried out in the Group Health Cooperative organization of Washington State, U.S. Simon et al.

(15) randomly assigned 441 patients to a 2-year systematic collaborative care program or treatment as usual (typically medication management visits). The probability of a new manic episode was significantly lower in the systematic care group over the eight assessment points of the study. Patients spent an average of 5.5 fewer weeks with clinically significant symptoms of mania than those in treatment as usual. Like the VA study, there were no effects of systematic care on depression severity, weeks depressed, or depressive recurrences. Of interest, the effects on mania severity scores were only observed among the 343 patients with moderate to severe symptoms at entry.

Family Psychoeducation

Multiple randomized trials indicate that behavioral family therapy is an effective adjunct to neuroleptics in delaying psychotic recurrences and improving functioning among patients with schizophrenia

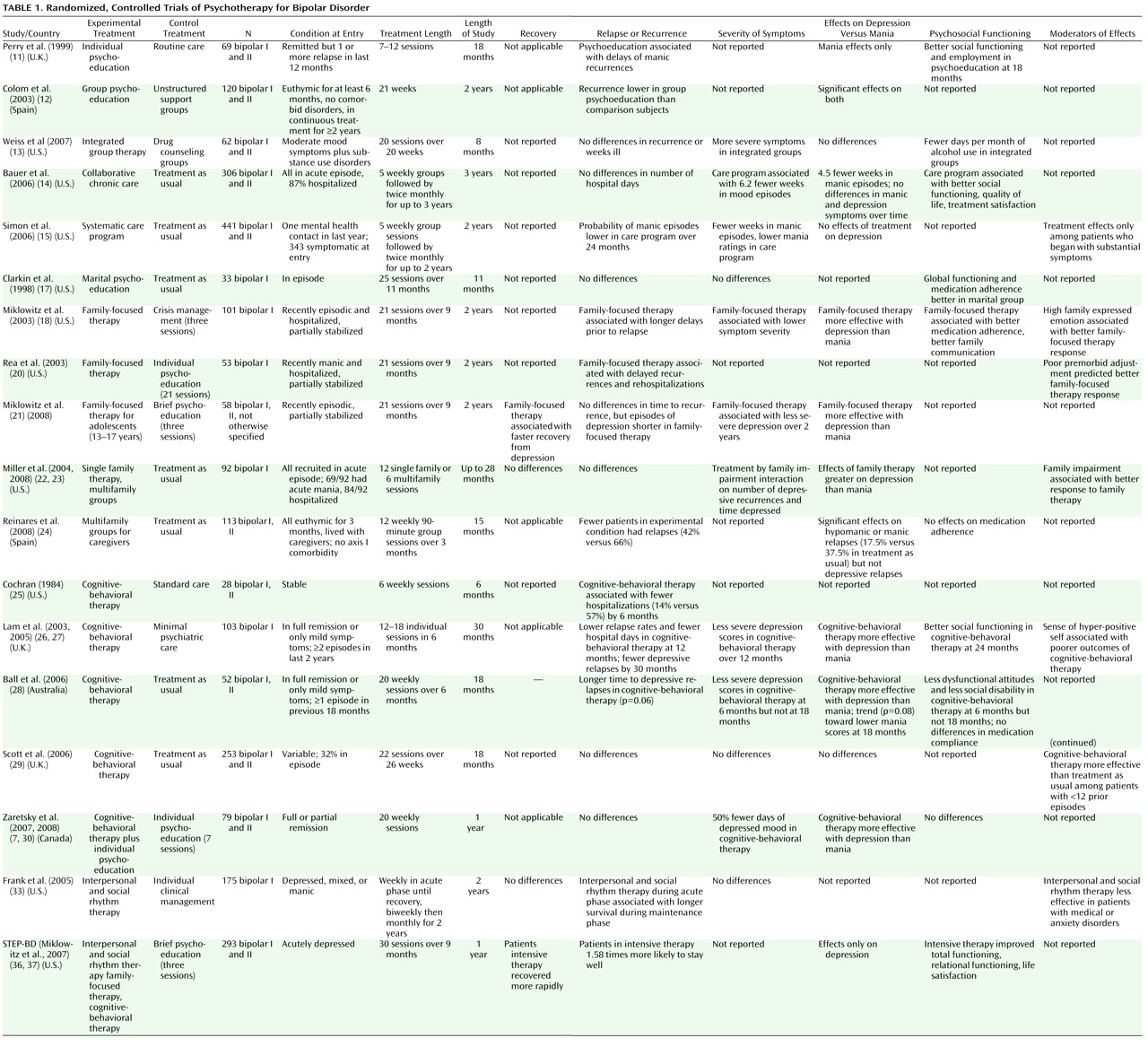

(16) . Likewise, several randomized, controlled trials have found that family psychoeducation is effective in enhancing the course of bipolar disorder (

Table 1 ). One small-scale trial (N=33) found that acutely ill patients receiving an 11-month psychoeducational marital intervention had better medication adherence and greater improvements in functioning than those receiving pharmacotherapy alone

(17) . No effects of the marital intervention were observed on symptomatic outcome.

Our research group has conducted three trials of family-focused therapy, which consists of 21 sessions of psychoeducation, communication enhancement training, and problem-solving. Family-focused therapy emphasizes strategies for regulating one’s emotions and enhancing interpersonal communication when facing conflicts (e.g., reflective listening; actively requesting support from family members). In the first trial

(18), we randomly assigned 101 adult patients shortly after an acute manic, mixed, or depressive episode (81% hospitalized) to family-focused therapy and pharmacotherapy or two sessions of family- based crisis management and pharmacotherapy. Over 2 years, patients in family-focused therapy had a greater likelihood of survival without disease relapse (52%) than patients in crisis management (17%) and survived longer without recurrence (mean=73.5 weeks) than patients in crisis management (53.2 weeks). The effects of family-focused therapy were stronger on depressive (p=0.005) than manic symptoms (p<0.05). The effects of family-focused therapy on depressive symptoms appeared to be mediated by improvements in communication between patient and relatives in a laboratory-based family interaction task

(19) . In contrast, the effects of family-focused therapy on mania symptoms appeared to be mediated by improvements in patients’ adherence with lithium and anticonvulsant regimens

(18) .

In a second trial

(20), we examined family-focused therapy and pharmacotherapy versus an individual therapy and pharmacotherapy in 53 bipolar I patients hospitalized for a manic episode. The individual therapy was of identical frequency (21 sessions) and length (9 months) and contained many of the same psychoeducational elements as family-focused therapy. At 1 year, no differences emerged in recurrence rates. However, over a 1–2 year posttreatment period, patients in family-focused therapy had a 28% recurrence rate and a 12% rehospitalization rate, compared to a 60% recurrence rate and a 60% rehospitalization rate for individual therapy. Mean survival times prior to recurrences were also longer in the family-focused therapy group.

Our third randomized trial examined the effects of adjunctive family-focused therapy (21 sessions) or a 3-session psychoeducational treatment on subsyndromally or acutely ill adolescents (mean age=14.5) who had had at least one episode of bipolar spectrum disorder in the prior 3 months

(21) . Adolescents assigned to family-focused therapy had more rapid recoveries from depressive states, spent less time in acute depressive episodes, and had a more favorable trajectory of depressive symptoms over 2 years than adolescents receiving pharmacotherapy and brief psychoeducation. The effects of family-focused therapy were not significant for manic symptoms.

Multifamily Psychoeducation Groups

Presumably, working with multiple families at once could be more cost-effective than working with families individually. Miller and associates

(22,

23) assigned 92 acutely ill (75% manic) bipolar I patients to pharmacotherapy alone, pharmacotherapy plus 12 sessions of single-family therapy (based on problem-centered systems therapy), or pharmacotherapy plus six sessions of multifamily psychoeducation groups. Over 28 months, no differences emerged between the three groups in time to recovery or recurrence. However, patients from families that were initially high in conflict or low in problem-solving and who received either form of family therapy had approximately half as many depressive episodes per year and spent less time in depressive episodes than those who received pharmacotherapy alone. There were no effects of either family intervention on mania symptoms and no differences in the outcomes of patients who received single family therapy or multifamily groups. The study is consistent with the family-focused therapy trials in showing stronger effects of family intervention on depressive than manic outcomes.

One study examined the effects of caregiver psychoeducation groups that did not involve patients

(24) . Participants were caregivers (62 parents and 45 partners) of 113 bipolar I and II patients treated at a bipolar clinic at the University of Barcelona, Spain. Patients had to be euthymic for 3 months, free of any other axis I disorder, and living with relatives. The caregivers were randomly assigned to 12 weeks of group psychoeducation or treatment as usual (pharmacological care for patients without caregiver groups). Similar to the family-focused therapy model, the caregiver groups focused on illness management skills (e.g., early detection of prodromes), medication adherence, and effective communication and problem-solving.

Over a 12-month posttreatment follow-up, patients whose relatives attended the groups had longer survival times prior to hypomanic or manic recurrences than patients in treatment as usual but did not differ on time to depressive or mixed episodes. Thus, caregivers may have been able to identify and intervene with patients’ manic prodromes without the input of the patients. In contrast, patient involvement may be necessary to extend the benefits of multifamily groups to the alleviation of depressive symptoms.

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy

Some bipolar patients have pessimistic explanatory styles in the depressive phases and overly optimistic explanatory biases in the manic or hypomanic phases of the illness

(5) . These thinking biases are the target of cognitive restructuring strategies. Cochran

(25) examined a six-session individual cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) in a small-scale randomized, controlled trial involving 28 stable bipolar I patients. The goal of the CBT was to alter cognitions and behaviors that interfered with lithium compliance. Relative to standard care (lithium alone), the intervention was successful over a 6-month follow-up in promoting compliance, reducing the proportion of patients requiring hospitalization and reducing the proportion of patients with mood episodes attributable to noncompliance.

Lam et al.

(26,

27) identified 103 bipolar I and II patients who were in recovery but had had at least three episodes in the past 5 years. Patients were randomly assigned to pharmacotherapy plus 12–18 individual CBT sessions over 6 months or pharmacotherapy plus routine care. The results over 1 year favored the CBT group (44% relapsed) over the routine care group (75%). Patients in CBT also had fewer hospitalizations and days in the hospital, better social functioning, and better medication adherence than those in routine care. At 30 months, the group difference in relapse rates was only significant for depressive relapses. Depression severity scores and days spent in depressive episodes were lower among CBT patients over 12 but not 30 months.

A single-site randomized, controlled trial (N=52) in Australia generally confirmed these results

(28) . Bipolar I and II patients who were euthymic or mildly symptomatic were randomly assigned to medication and 6 months (20 sessions) of CBT and “emotive techniques” (imagery, narratives, and reliving early experiences) or medication with brief psychoeducation (treatment as usual). Patients in CBT had lower depression scores at 6 months and tended to have longer times to depressive relapses over 18 months (p=0.06) but did not differ in overall relapse rates. Patients in CBT also had greater improvements in the severity of depressive symptoms relative to the 18 months preceding the study. As in the Lam et al.

(27) trial, the benefits of CBT on depression scores diminished over time, suggesting that booster sessions may be necessary for the maintenance of gains.

A five-site U.K. study of 253 bipolar I and II patients examined CBT in community centers serving highly recurrent patients

(29) . Most of the patients were “high risk” by virtue of having comorbid disorders (e.g., substance dependence), at least one episode in the prior year, current active symptoms (32% in acute episodes), or other risk factors. Patients in CBT underwent 22 sessions over 26 weeks, although patients attended an average of only 14 sessions (identical to the Lam et al.

[26] trial). The primary results were negative: over 18 months, patients in CBT did not differ from those in treatment as usual on time to recurrence, duration of illness episodes, or mean symptom severity scores. A post hoc analysis revealed that CBT was effective in delaying recurrences among patients with fewer than 12 prior episodes.

A maintenance randomized, controlled trial in Canada examined the effects of CBT in addition to individual psychoeducation

(7,

30) among 79 fully remitted or minimally symptomatic bipolar I and II patients on stable medications. All subjects received seven individual sessions of psychoeducation derived from a structured CBT manual; half also received 13 individual sessions of CBT. There were no differences in relapse or rehospitalization rates between the two study arms, but the patients in CBT had 50% fewer days of depressed mood and fewer antidepressant dosage increases over the study year.

Parikh and colleagues (personal communication, June 29, 2008) have recently concluded an effectiveness study of CBT versus psychoeducation across four Canadian sites with bipolar I and II patients (N=204) in full or partial remission. This 18-month trial compared pharmacotherapy plus 20 weeks of individual CBT to pharmacotherapy plus 6 sessions of group psychoeducation

(14) . Because the full results of this trial have not been published, it is not included in

Table 1 . Preliminary results, however, have shown no differences in outcome between the two interventions. The effectiveness of group psychoeducation cannot be assessed in this study because of the lack of a no-psychotherapy control.

The results of these trials yield inconsistent conclusions regarding the effectiveness of CBT. CBT may be more effective among recovered and less recurrent patients than among severely ill, highly recurrent patients. The effects of CBT on depressive outcomes appear to be more robust than on manic outcomes, except when medication compliance is the focus of treatment

(25) . Alternatively, differences among the studies in sample populations (e.g., number of prior episodes, clinical status at admission), therapy training procedures, consistency of the intervention components across settings, and other site or protocol variables may account for the discrepant results. For example, Lam et al.

(26) examined recovered patients, whereas Scott et al.

(29) included patients in a variety of clinical states, some of whom were not on mood stabilizers. Thus, conclusions regarding the status of CBT as a maintenance treatment await systematic trials that examine the moderating effects of patient, treatment, and setting variables.

Interpersonal and Social Rhythm Therapy

The interpersonal and social rhythm therapy approach, an adaptation of interpersonal psychotherapy for depression, derives from two observations: bipolar disorder is often associated with poor interpersonal functioning, especially during the depressive phases

(31) ; and disruptions into sleep/wake cycles can precipitate manic episodes

(32) . Accordingly, interpersonal and social rhythm therapy has two objectives: to resolve key interpersonal problems related to grief, role disputes, interpersonal conflicts, or interpersonal deficits; and to stabilize social rhythms (i.e., when patients arise, go to sleep, exercise, or socialize). Initiated during the postepisode period, patients are instructed to track and regulate their daily routines and sleep/wake cycles and identify events (e.g., changes in job hours) that could provoke changes to these routines.

In a single-center trial of this modality, 175 acutely ill bipolar I patients were assigned randomly to pharmacotherapy and weekly interpersonal and social rhythm therapy or pharmacotherapy and weekly clinical management sessions

(33) . Once recovered, patients were again assigned randomly to interpersonal and social rhythm therapy or clinical management for a 2-year maintenance period, with sessions tapered to monthly. The results generally supported the efficacy of interpersonal and social rhythm therapy. Patients who received interpersonal and social rhythm therapy during the acute phase had longer well intervals in the maintenance phase than patients assigned to clinical management in the acute phase. Interpersonal and social rhythm therapy was most effective in delaying recurrences in the maintenance phase when patients succeeded in stabilizing their social rhythms during the acute phase. In contrast, interpersonal and social rhythm therapy initiated during a period of recovery was no more effective than clinical management in preventing recurrences over 2 years. Secondary analyses revealed strong effects of interpersonal and social rhythm therapy relative to clinical management on depressive recurrences and a marginally significant effect on suicide attempts

(34,

35) .

A Comparison of Treatments for Bipolar Depression: STEP-BD

Few of the trials reviewed above compared two or more active treatments. In the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD; [references

36,

37 ]), an effectiveness study carried out in 15 U.S. sites, 293 acutely depressed patients with bipolar I or II disorder were randomly assigned to medication or any of four evidence-based psychosocial treatments: 30 weekly and biweekly sessions of family-focused therapy, interpersonal and social rhythm therapy, CBT, or a three-session psychoeducational control called collaborative care. Unlike prior studies, the primary outcome variable was recovery from an acute depressive episode. Treatments were carried out by therapists who received limited training and supervision (an 8-hour workshop in each modality followed by monthly teleconferences).

Over 1 year, being in any of the three intensive psychotherapies was associated with a faster recovery rate (169 days versus 279 days) from acute depression than being in collaborative care

(36) . Patients in intensive treatment were also 1.58 times more likely to be well in any month of the 1-year study than patients in collaborative care. Rates of recovery by 1 year did not differ significantly across the intensive modalities: family-focused therapy=77% (mean time to recovery=103 days), interpersonal and social rhythm therapy=65% (127.5 days), and CBT=60% (112 days). Patients in intensive psychotherapy also had greater gains in functional outcomes, including relationship functioning and life satisfaction, even after functioning scores were adjusted for concurrent levels of depression

(37) .

The results of STEP-BD underline the power of adjunctive psychosocial approaches, but also their limitations. Despite the availability of up to 30 sessions of care, patients attended an average of only 14.3 (SD=11.4) sessions. Only 54% of the patients had family members available to assist in family-focused therapy or other treatments. Psychotherapies affected relationship functioning but not vocational functioning; possibly, cognitive rehabilitation programs such as those for schizophrenia could be adapted to bipolar disorder

(38) . Nonetheless, bipolar patients with acute depression appear to require more intensive psychotherapy than is typically offered in community care. Possibly, the common ingredients of these intensive psychotherapies—such as teaching strategies to regulate mood states and resolve key interpersonal or family problems—contribute to more rapid recoveries and better functioning after a depressive episode.