The term “schizophrenia” was coined 100 years ago, on April 24, 1908, when

Paul Eugen Bleuler gave a lecture at a meeting of the German Psychiatric Association in Berlin (1): “For the sake of further discussion I wish to emphasize that in Kraepelin’s dementia praecox it is neither a question of an essential dementia nor of a necessary precociousness. For this reason, and because from the expression

dementia praecox one cannot form further adjectives nor substantives, I am taking the liberty of employing the word

schizophrenia for revising the Kraepelinian concept. In my opinion the breaking up or splitting of psychic functioning is an excellent symptom of the whole group” (2).

Kraepelin’s use of “dementia” derived from the Latin word mens and the prefix de-, expressing privation; it was a noun that implied a static condition. While Kraepelin selected descriptions of the symptoms and studied their time course mostly from patients’ records, Bleuler collected material directly from his passionate clinical work. By accommodating himself to the spatial and temporal environment of his patients, he realized that the condition was not a single disease (he referred to a “whole group” of schizophrenias [3]), was not invariably incurable, and did not always progress to full dementia, nor did it always and only occur in young people. The main symptoms of this disease were the loosening of associations, disturbances of affectivity, ambivalence, and autism (“the four A’s”) (4). However, the splitting of different psychological functions, resulting in a loss of unity of the personality, was the most important sign of disease in Bleuler’s conception (4). Thus, he challenged the accepted wisdom of the time and advanced his purportedly less static and stigmatizing concept by juxtaposing the Greek roots schizen (σχι´ζειν, “to split”) and phrēn, phren- (φρη´ν, φρεν-, originally denoting “diaphragm” but later changing, by metonymy, to “soul, spirit, mind”).

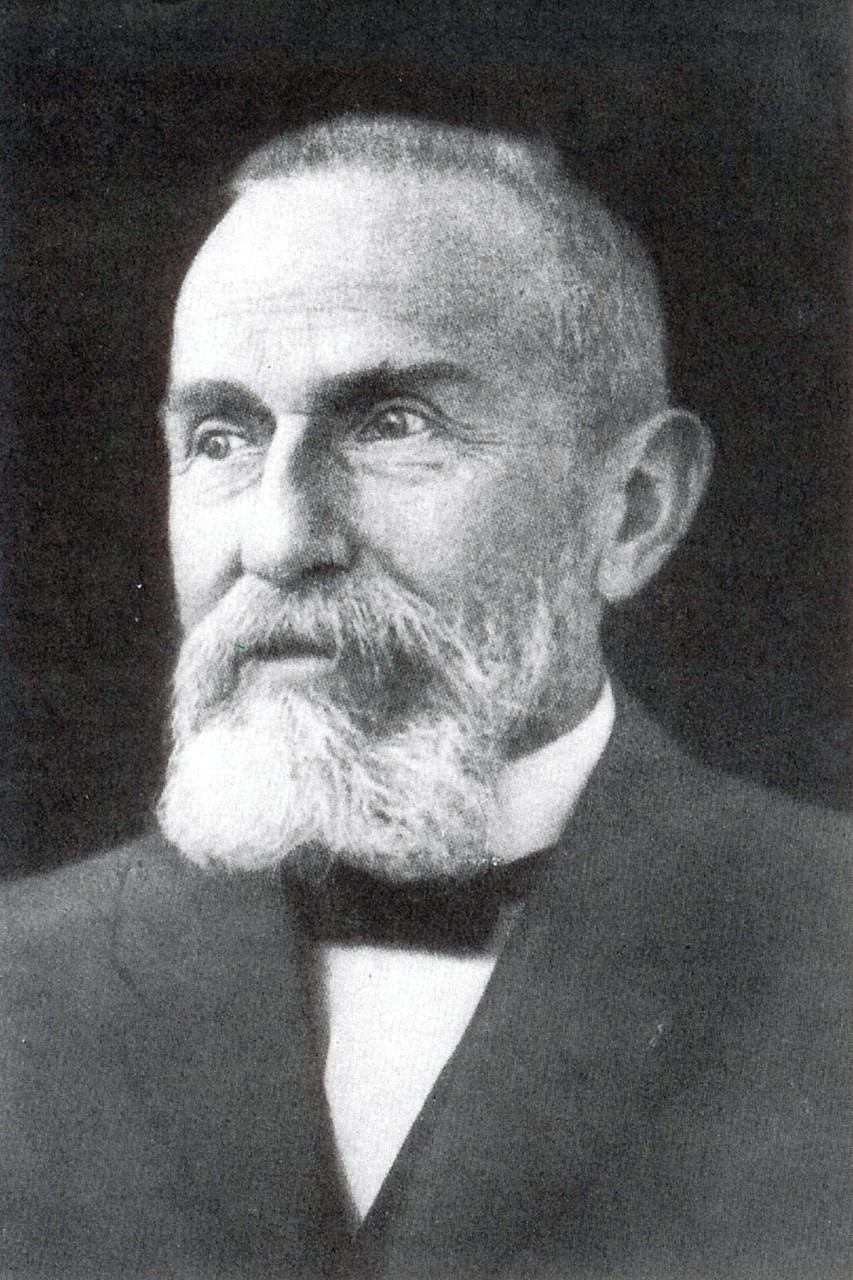

After completing his studies in medicine (1881) and mental and nervous diseases (1883), Bleuler visited Paris, London, and Munich. He became director of a small psychiatric clinic situated in an abandoned monastery on the Rhine (Rheinau, 1886–1898), then he was appointed professor and director of the Burghölzli Asylum in Zurich (1898–1927). Among his pupils there were such outstanding personalities as Carl Gustav Jung, Karl Abraham, Eugene Minkowski, Ludwig Biswanger, and Hermann Rorschach. He published the work “Dementia praecox oder Gruppe der Schizophrenien” in 1911 (3) and the book Lehrbuch der Psychiatrie in 1916 (5). He died in 1939 in Zollikon, Switzerland, where he had been born in 1857.