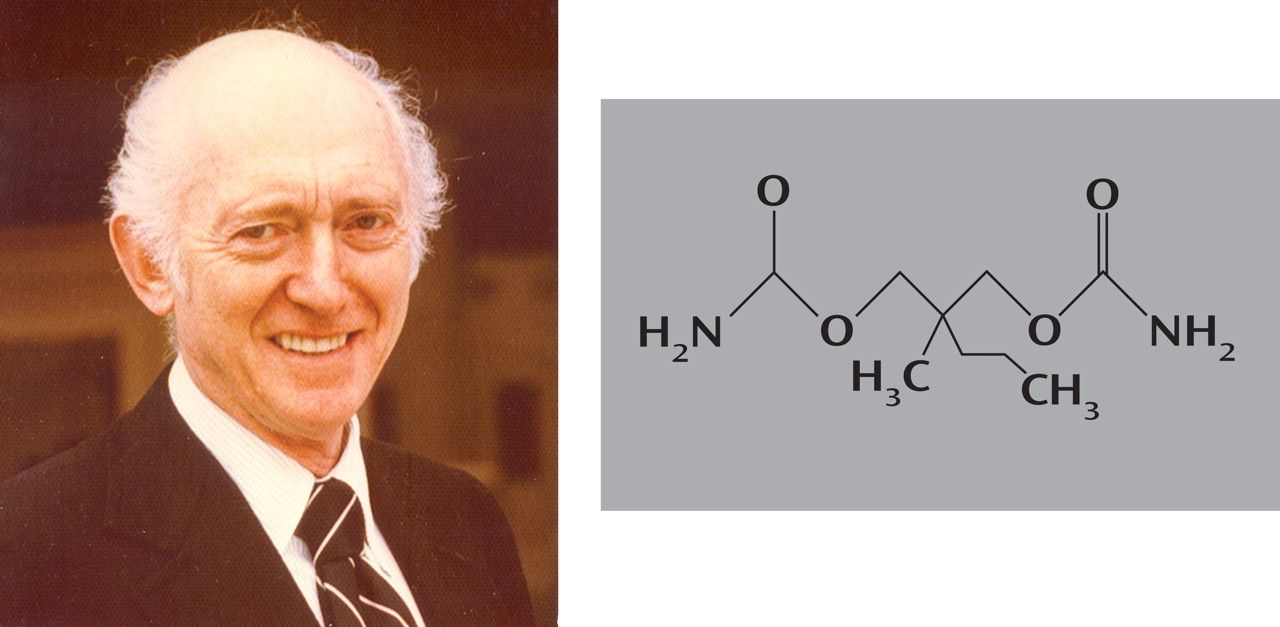

The discovery that ushered in the era of tranquilizers and other anxiety medications was Frank Berger’s discovery of meprobamate.

Frank Berger, M.D., was a microbiologist of Czech origin working in the United Kingdom during World War II. Shortly after Florey and colleagues purified penicillin, Berger was looking for a substance that would preserve penicillin by inhibiting penicillinase-producing bacteria. One of these substances, mephenesin (Myanesin) met this criterion. While performing toxicity studies, Berger noted that large doses of mephenesin produced tranquilization in laboratory animals. He published his findings in 1946 in the

British Journal of Pharmacology (1) .

Shortly after this discovery, Berger moved to the United States and worked at Carter Products (later Carter-Wallace), a small pharmaceutical company. There he continued working with mephenesin, investigating why it was metabolized rapidly. He and his co-workers found that mephenesin’s rapid deactivation by oxidation of its terminal hydroxy groups was best blocked by carbamates. They synthesized a few hundred carbamates. Meprobamate

(2) seemed to be “the best one.” Several clinical trials with meprobamate were conducted, one by Berger himself. To convince hesitant executives about meprobamate’s properties, Berger produced a short documentary showing the drug’s effect on rhesus monkeys. The brand name “Miltown,” after a small village near New Brunswick, N.J., was selected (meprobamate was also later distributed as “Equanil”). Meprobamate became extremely popular during the 1950s and opened the market to other “tranquilizing” drugs (e.g., chlordiazepoxide). Meprobamate relieved anxiety, relaxed muscles, and induced mild euphoria and “inner peace.” Some even suggested that it should be added to drinking water so the masses would be less anxious. Thus, it is interesting that the Associated Press reported in March 2008 that traces of meprobamate were found in water supplies of Los Angeles and several other places. Only a few years after its introduction, it became obvious that meprobamate could be habit forming, its sudden withdrawal could be dangerous, and overdose could be lethal. Its use decreased, especially after the arrival of benzodiazepines, but it never totally faded away. Generic meprobamate is still available.

Frank Berger continued his research and development of carbamates (e.g., the pain reliever carisoprodol) and later returned to bacteriology and immunology.

Berger is an example of an alert observer and astute researcher from the golden era of serendipity in psychopharmacology research, along with R. Kuhn, J. Delay, P. Deniker, and others. Recently, Donald Klein

(3) reminded us of “a seismic shift in psychiatry between 1950 and 1970,” the Age of Serendipitous Psychopharmacology Discoveries. During those times, lithium, chlorpromazine, iproniazid, meprobamate, chlordiazepoxide, haloperidol, and other psychotropic drugs were “discovered” mostly because of “chance observations of unexpected clinical benefits or as inadvertent outcomes of blind pharmaceutical searches”

(3) .