Cognitive Vulnerability

What developmental event or events might lead to the formation of dysfunctional attitudes and how these events might relate to later stressful events leading to the precipitation of depression was another piece of the puzzle. In our earlier studies, we found that severely depressed patients were more likely than moderately or mildly depressed patients to have experienced parental loss in childhood

(6) . We speculated that such a loss would sensitize an individual to a significant loss at a later time in adolescence or adulthood, thus precipitating depression. Brij Sethi, a member of our group, showed that the combination of a loss in childhood with an analogous loss in adulthood led to depression in a significant number of depressed patients

(7) . The meaning of the early events (such as “If I lose an important person, I am helpless”) is transformed into a durable attitude, which may be activated by a similar experience at a later time. A recent

prospective study observed that early life stress sensitizes individuals to later negative events through impact on cognitive vulnerability leading to depression

(8) .

The accumulated research findings have supported the original cognitive vulnerability model derived from clinical observations

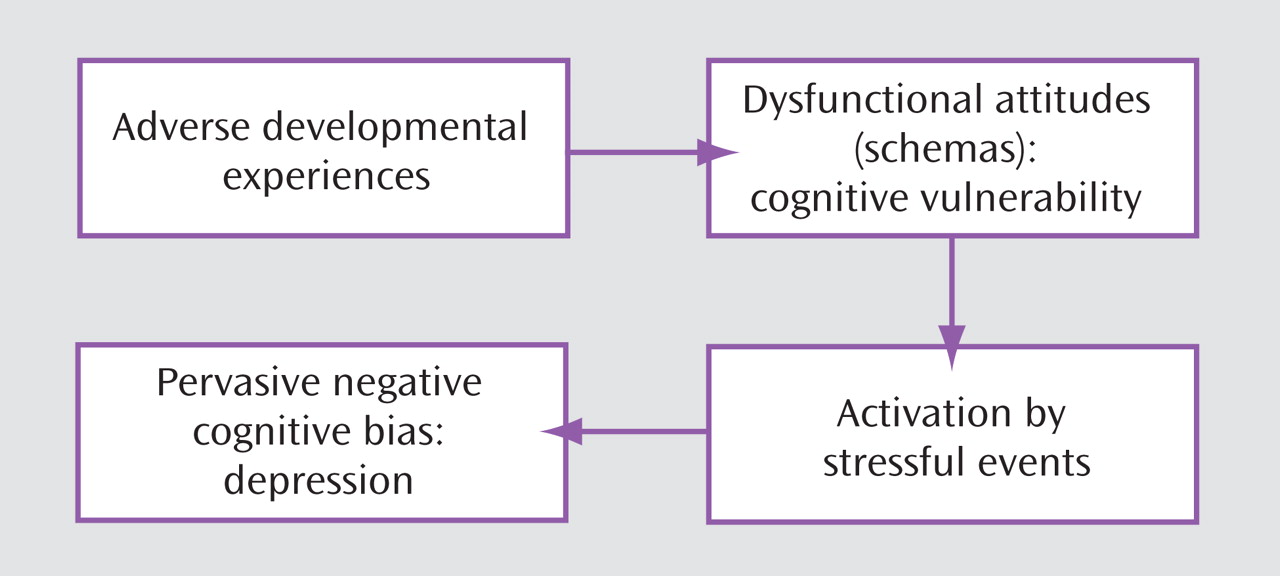

(4) . As shown in

Figure 1, early adverse events foster negative attitudes and biases about the self, which are integrated into the cognitive organization in the form of schemas; the schemas become activated by later adverse events impinging on the specific cognitive vulnerability and lead to the systematic negative bias at the core of depression

(1,

9) .

Much of the early research by others on the cognitive model overlooked the role of stress in activating previously latent dysfunctional schemas. Scher and colleagues

(10) provided a comprehensive review of the diathesis-stress formulation based on prospective studies and priming methodologies to test the cognitive model.

Although the original cognitive model proposed that severe life events (e.g., death of a loved one or loss of a job) were the usual precipitants of depression

(1), more recent research has suggested that milder stressful life events provide an alternate pathway to depression in vulnerable individuals

(11,

12) . Moreover, the triggering events of successive episodes of depression become progressively milder, suggesting a “kindling” effect

(13,

14) .

Cognitive vulnerability to the experience of depressive symptoms following stress has been reported in children, adolescents, and adults

(10,

12,

15) . For example, students showing cognitive vulnerability were more likely to become depressed following negative outcomes on college applications than were students not showing cognitive vulnerability

(12,

16) . It should be noted that these studies generally described minor depressive episodes rather than full-blown major depression.

What relevance do dysfunctional attitudes have to the vulnerability to

recurrence of depression? Segal and colleagues

(17) showed that the muted dysfunctional attitudes of recovered depressed patients could be primed by a negative mood induction procedure. Furthermore, the extent to which the mood induction activated the dysfunctional attitudes during the nondepressed period predicted future relapse and recurrence. This activation of the dysfunctional attitudes was more likely to occur with patients who had received pharmacotherapy than those receiving cognitive therapy. The prospective and priming studies thus indicated that dysfunctional attitudes could be regarded as a

cognitive vulnerability factor for depression.

A more recent refinement of the cognitive vulnerability model has added the concept of

cognitive reactivity, expressed clinically as fluctuations in patients’ negative attitudes about themselves in response to daily events

(18) . Cognitive reactivity has been demonstrated experimentally by a variety of priming interventions (or “mood interventions”) such as sad music, imaging of sad autobiographical memories, social rejection film clip, or contrived failure. Following these priming interventions, clinically vulnerable subjects report more dysfunctional attitudes, negative cognitive biases, and erosion of normal positive biases than do other subjects

(10) . Clinical vulnerability was defined in terms of high-risk variables (e.g., a personal or family history of depression).

Studies have shown that the presence of cognitive reactivity before a stressful life event predicts the onset of depressive episodes

(10) . The importance of the meaning assigned to a stressful event as a crucial component of cognitive reactivity was borne out by the finding

(19) that the daily negative appraisals of daily stressors predicted daily depressive symptoms. The addition of the concept of cognitive reactivity to the cognitive model suggested that the predisposition to depression may be observable in the

daily cognitive-emotional reactions of the depression-prone individual

(18) . However, the model left unanswered why certain individuals were more reactive to daily events (or were more likely to develop dysfunctional attitudes and cognitive biases) than others.

As indicated previously, the experience of episodes of depressive symptoms is different from the total immersion of the personality in a full-blown major depression. Severe depression is characterized not only by a broad range of intense symptoms but also “endogenous” features, such as relative insensitivity to external events. To account for the complex characteristics of the fully expressed depression, I proposed an expanded cognitive model

(4,

20) . I presented the concept of the

mode, a network of cognitive, affective, motivational, behavioral, and physiological schemas, to account for the profound retardation, anhedonia, and sleep and appetite disturbance, as well as the cognitive aberrations. The activation of this mode (network) produces the various phenomena of depression.

In the formation of the mode, the connections among the various negatively oriented schemas become strengthened over time in response to negatively interpreted events. Successive symptom-producing events or a major depressogenic event locks these connections into place. In a sense, the cognitive schemas serve as the hub and the other schemas as nodes with continuous communication among them. A major stressful event or events symbolizing a loss of some type trigger the cognitive schemas that activate the other (affective, motivational, etc.) schemas. When fully activated, the mode becomes relatively autonomous and is no longer as reactive to external stimuli; that is, positive events do not reduce the negative thinking or mood. Attentional resources are disproportionately allocated from the external environment to internal experiences such as negative cognitions and sadness, manifested clinically as rumination. Also, resources are withdrawn from adaptive schemas such as coping and problem solving. The mode presumably would correspond to a complex neural network, including multiple relevant brain regions that are activated or deactivated during depression.

The negatively biased cognitive schemas function as automatic information processors. The biased automatic processing is rapid, involuntary, and sparing of resources. The dominance of this system (efficient but maladaptive) in depression could account for the negative attentional and interpretational bias. In contrast, the role of the cognitive control system (consisting of executive functions, problem solving, and reappraisal) is attenuated during depression. The operation of this system is deliberate, reflective, and effortful (resource demanding), can be reactivated in therapy, and, thus, can be used to appraise the depressive misinterpretations and dampen the salience of the depressive mode.

The concept of the two forms of processing can be traced back to Freud’s model of primary and secondary processes

(21) and has been reformulated many times since

(22) . Recently, Beevers

(23) suggested a similar formulation of a two-factor processing in depression. He proposed that cognitive vulnerability to depression occurs when negatively biased associative processing is uncorrected by reflective processing.

The expanded cognitive model includes the following progression in the development of depression: adverse early life experiences contribute to the formation of dysfunctional attitudes incorporated within cognitive structures, labeled cognitive schemas (cognitive vulnerability). When activated by daily life events, the schemas produce an attentional bias, negatively biased interpretations, and mild depressive symptoms (cognitive reactivity).

After repeated activation, the negative schemas become organized into a depressive mode, which also includes affective, behavioral, and motivational schemas (cognitive vulnerability). Accumulated negative events or a severe adverse event impacts on the mode and makes it hypersalient. The hypersalient mode takes control of the information processing, reflected by increased negative appraisals and rumination. The cognitive control of emotionally significant appraisals is attenuated and, thus, reappraisal of negative interpretations is limited. The culmination of these processes is clinical depression. Crick and Dodge

(24) point out that with repeated activation, maladaptive information-processing patterns become routinized and resistant to change. Thus, cognitive schemas, after repeated activation before and during depressive episodes, become more salient and more ingrained over time, consistent with the “kindling” phenomenon.

Although supportive evidence for this model was meager in early years, support for the fundamental hypotheses has accumulated over the past 40 years. In 1999, David A. Clark and I

(4) reviewed over 1,000 publications relevant to the cognitive model of depression and found substantial research support for the various facets of the cognitive theory. Several more recent reviews have provided additional research support

(10,

12,

15,

25) .

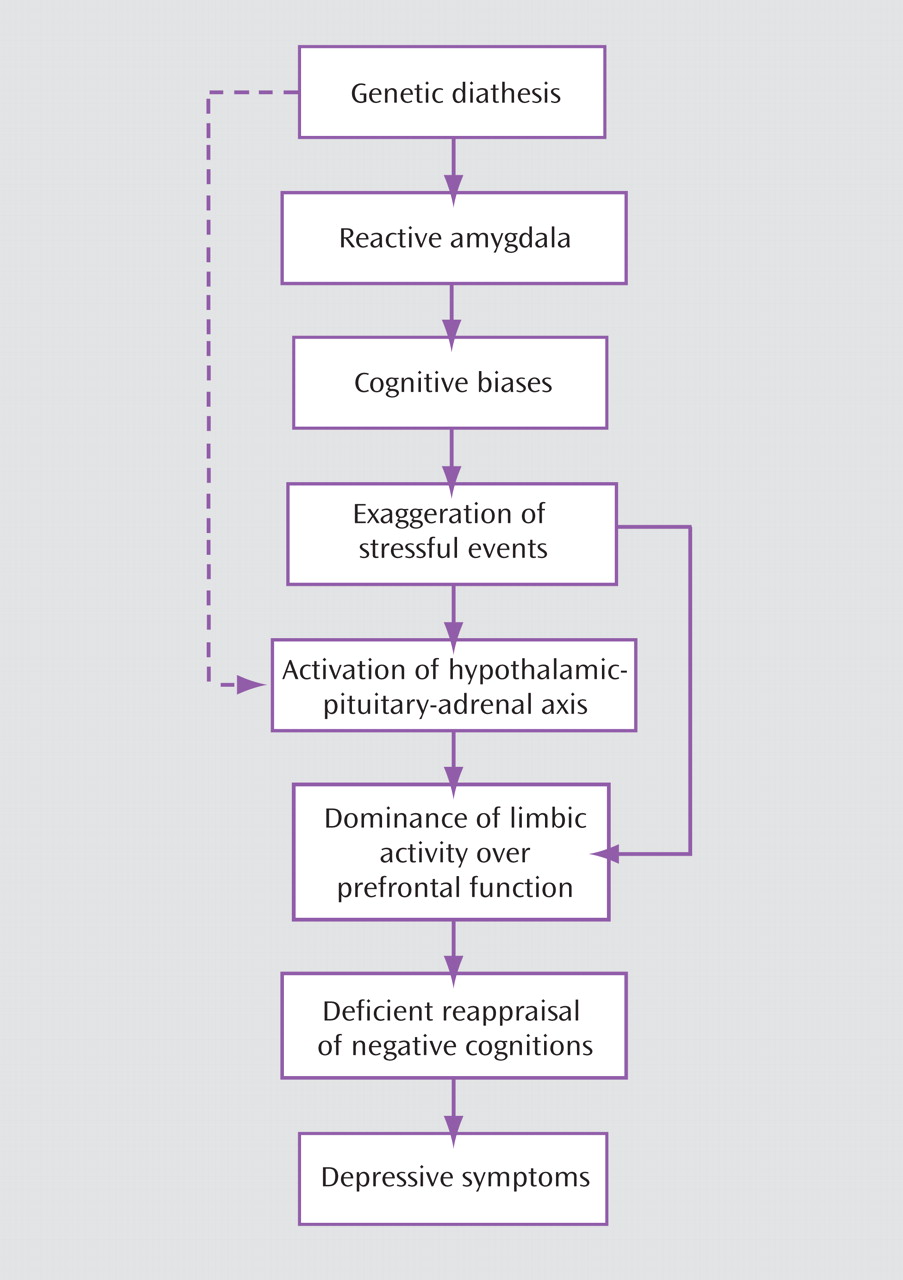

As the cognitive model of depression buttressed by years of systematic research has grown to maturity, it seems timely and appropriate to compare it with the burgeoning findings in neurogenetics and neuroimaging.