Two articles in this issue of the

Journal highlight the role of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-ergic signaling in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. The first article, by Lewis and colleagues

(1), reports the outcome of a double-blind trial that involved 15 subjects with schizophrenia treated with either placebo or a benzodiazepine-like compound, MK-0777. Subjects remained on their antipsychotic medications throughout the entire 4-week trial, and—in terms of some clinical measures (e.g., Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale)—there were no significant effects. However, subjects on MK-0777 did better than the placebo group on neuropsychological tests designed to measure 1) working memory, defined as the ability to maintain goal-directed information online, or 2) “cognitive control,” which requires focused attention and inhibition of prepotent response tendencies. The neural circuitry involved in these types of tasks includes the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. The subjects also underwent a task-related EEG recording, and, indeed, computational analyses revealed a trend toward increased 40 Hz activities over the left frontal region for the MK-0777 group. This frequency is part of the gamma range (30–200 Hz) of synchronized oscillations of neuronal assemblies in the cortex

(2) . Such coordinated neuronal activity within and also between cortical areas is thought to be important for the optimization of working memory and various cognitive processes, and there is mounting evidence that it is dysregulated in schizophrenia and other neuropsychiatric disease

(2) . So far, so good. But how do these findings relate to the study drug MK-0777 and to the GABAergic system?

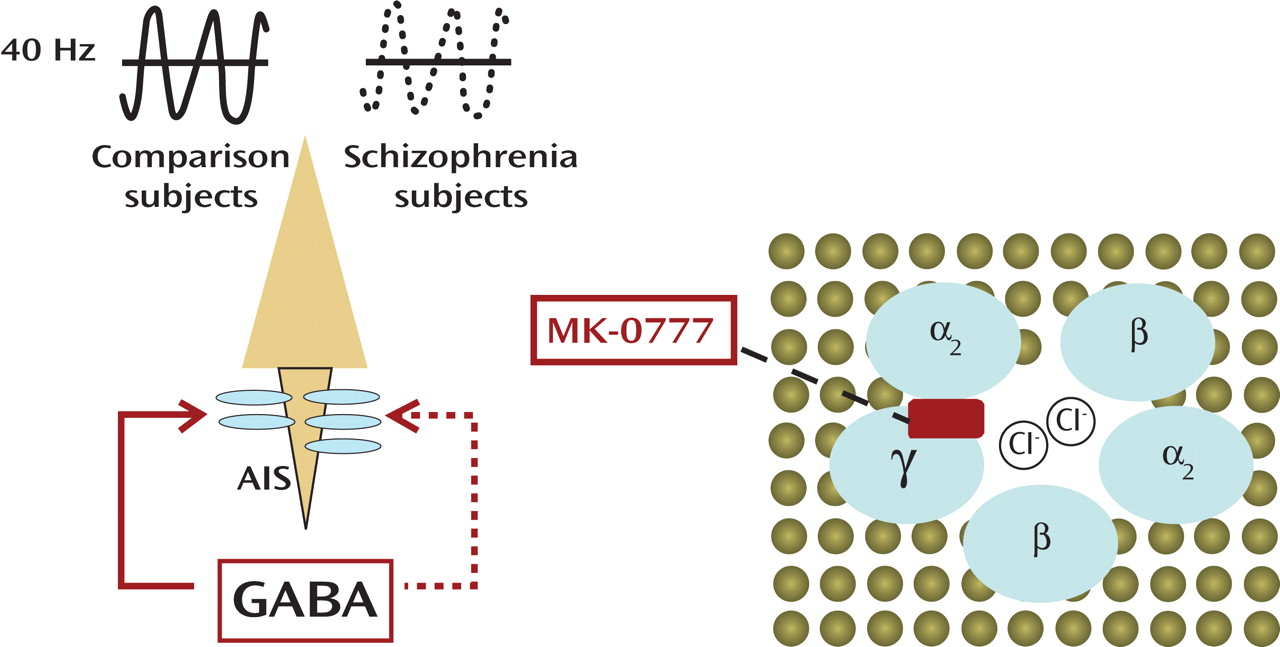

The mechanism of action of MK-0777 becomes clear within the context of GABA type A (GABA

A ) receptor molecular biology and pharmacology (

Figure 1 ). The GABA

A receptors are ligand-gated chloride ion channels that are typically comprised of two α subunits, two β subunits, and one γ subunit. (In contrast, GABA

B receptors, which are the target of the muscle relaxant baclofen, belong to the group of G-protein coupled receptors.) Activated GABA

A receptors effectively hyperpolarize mature neurons through changes in the chloride conductance. Benzodiazepines act as positive allosteric modulators by facilitating the action of presynaptically released GABA and bind at the interface of α and γ subunits

(3) . However, the benzodiazepine sensitivity of the receptor shows important differences and is highly dependent on the specific α subunit. There are altogether six α subunits (α

1– α

6 ) in the human genome, two of which (α

4 and α

6 ) are benzodiazepine insensitive as a result of the absence of a specific histidine residue. On the other hand, the high affinity of currently prescribed benzodiazepines for α

1 containing GABA

A receptors, which are predominant in the human cerebral cortex, could explain the sedative effects of these drugs

(3) as well as a further impairment of prefrontal dysfunction in subjects with schizophrenia

(4) . In contrast to the currently prescribed benzodiazepines, MK-0777, which is presently also used in clinical trials for anxiety spectrum disorders, causes much less sedation because it exerts selective activity at GABA

A receptors containing α

2 and α

3 subunits. Importantly, α

2 subunits are highly enriched at the axon initial segment (a cellular compartment that is critical for axon potential generation) of pyramidal neurons, which comprise the output relay of the cerebral cortex

(1) . However, the axon initial segments of many pyramidal neurons are among the postsynaptic targets of a subtype of GABA neurons that express the calcium buffer protein parvalbumin and show a specific firing pattern defined as “fast-spiking”

(1) . Intriguingly, the parvalbumin positive GABA neurons regulate and coordinate the timing of pyramidal neuron firings and, therefore, are essential for orderly gamma oscillations and memory function, all of which become disrupted when fast-spiking synaptic currents are down-regulated

(5) . Given the evidence from postmortem brain studies that parvalbumin positive neurons are dysfunctional, Lewis and colleagues

(1) hypothesized that enhanced signaling through α

2 subunit harboring GABA

A receptors at the pyramidal cell axon initial segment could improve gamma oscillations and prefrontal cognitive functions in schizophrenia subjects. Indeed, the data from the MK-0777 trial provide the first empirical support for this hypothesis, although additional studies with larger cohorts and inclusion of both genders will be necessary in order to reach a definitive conclusion. It is pleasing to witness how basic neuroscience research, in combination with human postmortem brain studies, gave rise to a novel hypothesis that subsequently is tested in the clinical setting.

The second article, by Bullock and colleagues

(6), examines molecular alterations of the GABAergic system in the

cerebellar cortex, using a case-control design for 13 subjects with schizophrenia (all of whom were treated with antipsychotics prior to death) matched with nonpsychiatric comparison subjects. The cerebellar cortex is commonly divided into 10 lobules, many of which are interconnected with the frontal lobe via relays in the pontine nuclei and a return projection through the thalamus

(7) . The study by Bullock and colleagues focused on a portion of lobule VII that is interconnected with the prefrontal cortex

(7) . The authors confirmed for their schizophrenia cases some of the alterations in cerebellar mRNA and proteins that were previously reported in other brain collections

(8), including a deficit in expression of glutamic acid decarboxylase 1 (

GAD1 [

GAD 67 ]) and

GAD2 (

GAD 65 ), the two rate limiting enzymes for GABA synthesis. Importantly, treatment of rats with either a typical (haloperidol) or an atypical (clozapine) antipsychotic induced an increase in GABAergic mRNAs in the cerebellar cortex

(6), which suggests that the observed decrease in the clinical samples is related to the disease process and not due to the medication. The study

(6) is based entirely on quantifications of RNAs extracted from tissue, and therefore it remains to be determined which of the four subpopulations of GABAergic neurons in the cerebellar cortex (Purkinje, stellate, basket, or Golgi cells) are affected. However, as the authors summarized in Figure 3

(6), their work suggests that many of the observed mRNA changes point to the Golgi neurons. This is interesting because these cells play a key role in the inhibition of the glutamatergic type of cerebellar neurons: the granule cell. Thus, in striking analogy to the cerebral cortex, cerebellar cortex function in schizophrenia could also be compromised by a deficit in inhibitory control over excitatory circuitry. To date, the apparent similarities in GABAergic deficits of the cerebral and cerebellar cortices in schizophrenia are puzzling and lack a straightforward explanation. It will be interesting to explore, in preclinical models, whether or not cerebellar Golgi cell dysfunction “resonates” through the above mentioned cortico-cerebellar loops, thereby interfering with prefrontal functions.

The context of the two studies

(1,

6) has more substance to it than mere academic interest. As pointed out by Lewis and colleagues, cognitive deficits are not necessarily related to psychotic symptoms, yet a predictor of functional outcome in schizophrenia. Given the emerging role of GABAergic systems for some of the cognitive defects of the disorder, it is interesting to note that a subset of GABAergic genes, including the α

2 subunit of the GABA

A receptor and

GAD1 /

GAD 67, are epigenetically modified throughout development and aging of the human cerebral cortex

(9,

10) . Therefore, it remains a possibility that targeted interventions for specific GABAergic deficits even prior to the appearance of overt psychosis in high-risk individuals could significantly alter the course of the illness or even prevent it altogether.