The ENRICHD Study

The Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease (ENRICHD) study was a multicenter, randomized, controlled clinical trial designed to determine whether treating depression and low perceived social support reduces the risk of recurrent infarction and death after an acute myocardial infarction

(12) . Patients with major or minor depression, and/or low perceived social support, were randomly assigned to usual care or an intervention that provided up to 6 months of cognitive behavior therapy (CBT). In addition, sertraline was given for up to 1 year to patients in the intervention arm who either had severe depression (HAM-D 17 score >25) at enrollment or whose score on the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) did not improve at least 50% after 6 sessions of CBT. Among the depressed patients, 6-month mean BDI change scores were –8.6 (SD=9.2) and –5.8 (SD=8.1) in the intervention and usual care arms, respectively. However, there was no between-group difference in reinfarction-free survival during a median of 29 months of follow-up

(13) .

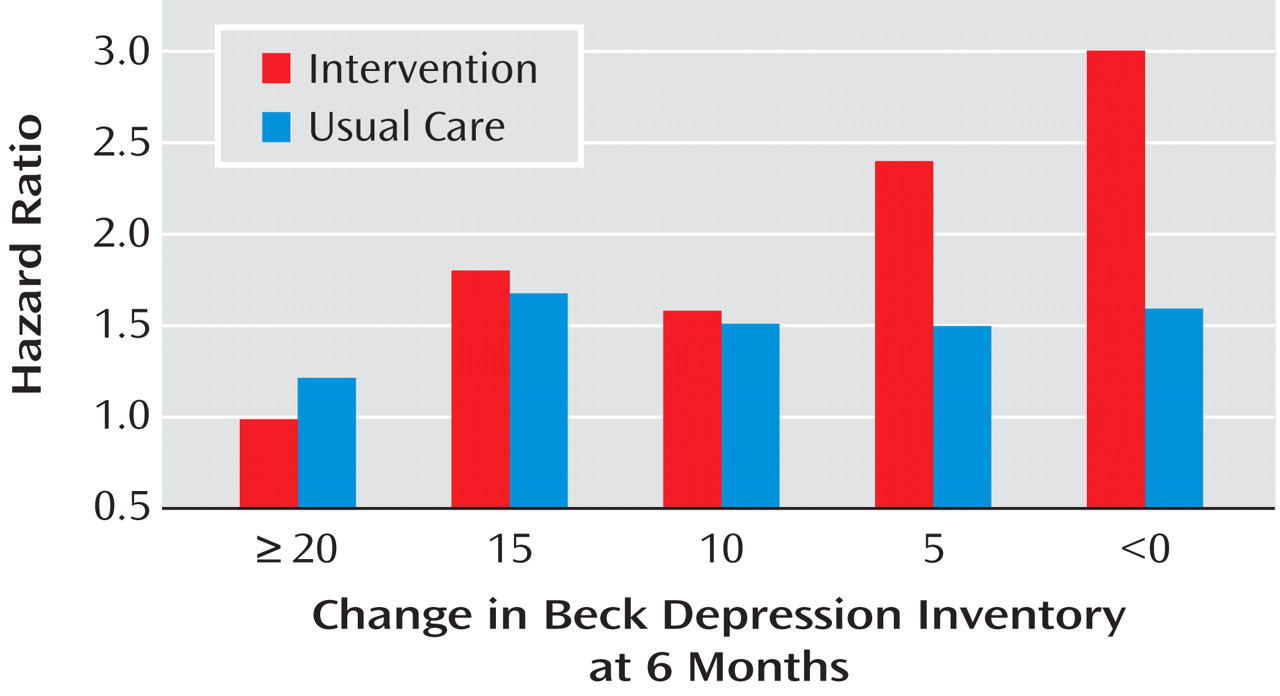

However, among patients with major depression in the intervention group, those who did not experience treatment response had a higher risk of late mortality (i.e., death occurring ≥6 months after the acute myocardial infarction) relative to those whose depression responded to treatment

(14) . Patients whose depression worsened by ≥10 BDI points despite treatment were 1.6 times more likely to die in the ensuing months than were those who merely failed to improve (i.e., no or minimal change in BDI score), and 2.5 times as likely to die as those who improved by 10 or more points on the BDI. These effects were independent of the baseline BDI score, antidepressant use, and established predictors of mortality following myocardial infarction, including left ventricular ejection fraction, age, and prior history of myocardial infarction. Curiously, although there was a strong relationship between change in depression and late mortality in the intervention arm, the relationship was not significant in the usual care arm (

Figure 1 ). Although fewer subjects in the intervention (15%) than the usual care (26%) arm failed to show any improvement in BDI score from baseline to 6 months (defined as a 6-month BDI score that was equal to or higher than the baseline BDI score), the mortality rate among nonimprovers was higher in the intervention arm (21%) than in the usual care arm (10%) of the trial.

For patients in the intervention group, the lack of improvement occurred despite receiving 6 months of aggressive treatment. However, only about 15% of the usual care patients received any form of nonstudy treatment for their depression during the first 6 months. Even fewer of the patients in the usual care arm who did not experience improvement had received any depression treatment. Some of them might not have achieved remission even if they had been treated, but others might have responded very well to treatment had it been provided. Although the subgroup sample sizes were small and the effect was not significant, there was a stronger relationship between treatment nonresponse and late mortality among patients in the intervention group who received both sertraline and CBT than those who received only CBT. Similarly, among patients in the usual care group who took nonstudy antidepressants, there was a twofold difference in mortality between those with the best and worst treatment responses

(14) . Relatively few usual care patients were treated, and the effect was not statistically significant. Nevertheless, these findings suggest that exposure to the ENRICHD intervention identified patients with a high-risk subtype of depression, i.e., depression that does not respond to standard antidepressant therapy.

Other Clinical Trials

There is evidence from other clinical trials supporting this conclusion. The Myocardial INfarction and Depression Intervention Trial (MIND-IT) compared 24 weeks of usual care versus mirtazapine versus placebo, followed by open-label citalopram among those whose illness was not responsive to treatment

(15) . Like the ENRICHD study, MIND-IT failed to demonstrate the superiority of the study interventions over usual care with respect to cardiac event-free survival during an average of 27 months of follow-up

(15) .

In a recent secondary analysis, de Jonge et al.

(16) classified patients in the MIND-IT intervention group as those who experienced response (≥50% improvement on the HAM-D at 24 weeks) or nonresponse (<50%). They compared these two subgroups to patients in the usual care arm who did not receive any treatment for depression. The 18-month incidence of cardiac events was 26% among intervention group patients whose illness was nonresponsive to treatment, 11% in untreated control subjects, and 7% among intervention group patients who experienced response (p<0.001). These findings are strikingly similar to the ENRICHD outcomes. Also like ENRICHD, the MIND-IT findings could not be explained by between-group differences in the initial severity of medical illness. Specifically, patients with treatment-responsive and -nonresponsive depression in MIND-IT did not differ in age, left ventricular ejection fraction, Killip class, the Charlson Comorbidity Index, or in the prevalence of diabetes, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral vascular disease, hypercholesterolemia, smoking, or prior revascularization.

The Montreal Heart Attack Readjustment Trial (MHART) tested the efficacy of a 12-month, home-based nursing intervention targeting emotional distress in post-myocardial infarction patients

(17) . Although depression per se was not the primary target of the intervention, over one third of the intervention patients had clinically significant depression (BDI >10) at baseline. Like MIND-IT and ENRICHD, the MHART intervention also failed to improve post-myocardial infarction survival.

A 5-year follow-up of the usual care arm of MHART showed that improvement in depression after 1 year was associated with lower cardiac mortality only in patients who had mild depression at baseline

(18) . There was no relationship between change in depression and subsequent mortality among patients who had moderate to severe depression at baseline, the very patients who may be considered for treatment in clinical settings.

This report did not include comparable analyses of the outcomes within the intervention arm. In unpublished analyses, however, the MHART investigators found a relationship between BDI change from baseline to 3 months and 5-year survival in the intervention (p<0.0001) but not in the usual care arm (p=0.98) (Frasure-Smith, personal communication, 2004). Only 6% of the patients in the intervention arm who were in the highest quintile of improvement on the BDI died within the first year, compared to 17% of patients in the lowest quintile. Thus, there is a striking similarity between the MHART and ENRICHD findings.

The Sertraline Antidepressant Heart Attack Randomized Trial (SADHART) was designed to determine the safety and efficacy of sertraline in patients with a recent acute coronary syndrome. At the completion of the trial, the sertraline and placebo arms did not differ on the HAM-D in the overall sample. However, there was a statistically significant difference in HAM-D outcomes in the subgroup with severe, recurrent major depression. There was also a trend toward fewer cardiac events in the sertraline arm

(19) .

The SADHART investigators recently completed a long-term follow-up (median 6.6 years) of the trial participants. They found a significant relationship between improvement in depression during the 24 weeks of treatment and survival in both the sertraline and placebo arms, even after adjusting for other mortality risk factors

(20) . Using the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) scale to measure improvement in depression following treatment, they found that the patients in both the placebo and sertraline groups with the most improvement (N=130) had the lowest rate of mortality (11.5%). For those with moderate improvement (N=80), 22.5% died; and for those whose depression minimally improved, worsened, or stayed the same following treatment (N=148), 28.4% died during the follow-up interval (p=0.001).

Unlike ENRICHD and MHART, the control group in SADHART also showed a relationship between improvement in depression and survival. However, a placebo condition and a usual care or no-treatment control group are not equivalent. A review of the efficacy data reported for placebo-controlled antidepressant trials found that the average HAM-D difference between drug and placebo groups is just 2 points (range=0.89 to 3.21)

(21,

22) . Although the placebo is pharmacologically inert, the clinical management that is provided to a patient in a double-blinded study is often perceived as supportive and beneficial. Simply meeting with patients to discuss their depression symptoms, encouraging them to take the pills as prescribed, and to return for the next scheduled visit may be therapeutic. For example, in a study of 248 patients with coronary heart disease, Lespérance et al.

(23) found greater depression improvement in patients who received only clinical management compared with those who received clinical management plus interpersonal psychotherapy, a recognized treatment for depression in psychiatric patients.

The relationship between treatment-resistant depression and cardiac mortality and morbidity extends beyond traditional treatments for depression. Milani and Lavie

(24) studied 522 coronary heart disease patients in a cardiac rehabilitation aerobic exercise program. The participants were assessed for depression symptoms before and after the program. A comparison group (N=179) was assessed at baseline but not at follow-up. The mortality rate among the depressed patients who completed the training but who remained depressed was significantly higher (22%) than that of the nondepressed participants (5%) and of the initially depressed patients whose mood improved following the exercise program (8%, p=0.0004). Thus, patients whose depression did not respond to exercise training had a three- to fourfold higher risk of dying than depression responders and nondepressed patients. Exercise training can therefore be added to the list of depression interventions, including sertraline, mirtazapine, citalopram, cognitive behavior therapy, and stress management, in which nonresponse is associated with an increased risk of mortality.

Milani and Lavie’s

(24) findings are consistent with our hypotheses. However, they do not reveal whether patients with persistent,

untreated depression (a subgroup which includes both potential treatment responders and potential nonresponders) are also at increased risk for mortality because they did not assess depression in the comparison patients during follow-up.

Taken together, these findings, especially those from the ENRICHD, MIND-IT, SADHART, and MHART clinical trials, suggest that unsuccessful treatment of depression after hospitalization for acute coronary syndrome identifies a high-risk patient subgroup. This may help to explain the failure of ENRICHD and the other clinical trials to improve survival. Although depression may have improved slightly more on average in the patients who received the intervention than in those who received usual care, the patients who were at the highest risk for cardiac events did not improve despite treatment, and they were at higher risk for cardiac events after treatment than were the responders. Because the participants in these trials were randomly assigned to treatment or control conditions, patients with potentially treatment-resistant depression were probably equally distributed between the groups. In the usual care groups, in which most patients did not receive any nonstudy treatment for depression, the potential nonresponders cannot be easily distinguished from potential responders who were simply never treated.