Major depression is predicted to become the second leading cause of disability in the world by 2020

(1) . Depression is one of the most common mental health problems among adolescents and is associated with increased morbidity and mortality: 10%–15% of youths are estimated to suffer from major depression by age 18, 28.3% of high school students report periods of impairing depression during the past year, and youth depression is associated with an increased risk of suicide and suicide attempts, social impairments, substance abuse, and adult depression

(2 –

4) .

Despite evidence of clinical and social morbidity and evidence of effective treatments, many depressed youths go untreated, and outcomes for depression treatment as delivered in routine clinical settings appear poor, with a meta-analysis suggesting a mean effect size near zero

(5) . This state of affairs has underscored the need to identify effective strategies for delivering evidence-based care within practice settings and to understand the outcome consequences.

Primary care is a major point of health service contact for youths and offers valuable opportunities to improve depression care

(6,

7) . Quality improvement interventions aimed at increasing rates of evidence-based depression care for adults in primary care have resulted in significant improvements in short- and long-term outcomes

(7 –

11) . However, rates of detection and treatment of depression are low for youths in primary care settings, and research evaluating quality improvement in youth populations has just begun

(6,

7) . Efficacy studies for adolescent depression treatment suggest that evidence-based psychotherapies, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), are effective

(4,

12) . Despite controversies over antidepressant medication in terms of both modest effects relative to adult studies and concerns about an increased risk of suicidality, the research supports the efficacy of fluoxetine and combined treatment with medication and CBT for moderate to severe depression in adolescents

(4,

13 –

15) . Few studies of depression treatment in adolescents have included long-term outcome data, and it has been difficult to demonstrate long-term benefits from depression treatments in youths, given the high natural recovery rate in this population

(16 –

18) .

The Youth Partners in Care study is a large randomized controlled trial designed to evaluate the effectiveness of a quality improvement intervention for depression, relative to treatment as usual enhanced by provider education, for depressed primary care patients 13–21 years of age

(19) . The intervention was a 6-month quality improvement program designed to improve access to evidence-based CBT and antidepressant medication through primary care. The study was initiated prior to controversies over the risk of suicidality in youths on some antidepressant medications

(14) . To support feasibility in primary care settings, depression status was assessed using a brief screening instrument that could be completed while patients waited for the primary care visit. As a result, some youths screened positive, meeting criteria for depressive disorders, and others had subsyndromal depressive symptoms. We previously reported short-term outcomes

(19), which indicated significant advantages of the intervention relative to treatment as usual, on depression outcomes, quality of life, and satisfaction with mental health care at 6-month follow-up. Patients in the intervention group also reported increased rates of specialty mental health care, particularly psychotherapy or counseling, with no evidence for increased use of antidepressant medications.

In this study, we examined effects of the Youth Partners in Care intervention on process and outcomes of care through 18 months and considered evidence for an indirect long-term outcome effect through the early effects on depression observed at 6 months. Direct effects are attributable to factors that the intervention directly changed, such as increased treatment rates and satisfaction with care

(19) . Direct effects might be expected at 12 and 18 months if the intervention led to longer-term change in patterns of treatment use by patients or treatment delivery providers or to persistent change in behaviors that were the direct focus of therapy. An indirect effect is an influence of the intervention on outcome through an intermediate factor. For example, indirect intervention effects on 18-month outcomes could occur if the relief of depression due to the intervention at 6 months reduced clinical risk factors for chronic or recurrent depression or stimulated other behavioral changes that were not the direct focus of therapy but nevertheless lowered the risk for later depression. Based on previous studies indicating that the benefits of depression treatment in youths are most evident early

(16 –

18,

20), we hypothesized 1) that direct effects of the intervention on outcomes would be strongest at the 6-month postintervention evaluation, and 2) that there would be an indirect intervention effect on 18-month outcomes through a continuing effect of the improvement in depression outcomes at 6 months. We also explored indirect quality improvement effects on quality-of-life outcomes.

Method

The Youth Partners in Care study is a multisite randomized effectiveness trial comparing the quality improvement intervention with an enhanced treatment-as-usual control group. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards from all participating organizations. After being given a complete description of the study, all participants, as well as legal guardians for youths under age 18, provided informed consent or assent. Because the study design is described elsewhere

(19,

21), we provide only a brief overview below.

Sample and Design

Six study sites were selected from five health care organizations to include public sector (two sites), managed care (two sites from one organization), and academic health programs (two sites). Participants were recruited and enrollment eligibility determined through in-clinic screenings of a consecutive sample of patients using brief self-administered questionnaires. Eligibility criteria were either a score ≥24 on the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; 22) or endorsement of “stem items” for major depression or dysthymia from the 12-month Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI), modified slightly to conform to diagnostic criteria for adolescents, 1 week or more of past-month depressive symptoms, plus a CES-D score ≥16. Following common adolescent medicine practices

(23), we defined adolescence broadly to include youths up to age 21. Patients were eligible for inclusion if they were 13–21 years of age and presented at one of the clinic sites for a primary care visit. Patients were excluded if they had previously completed the screening instrument, if they did not speak English, if their provider was not in the study, or if they had a sibling in the study.

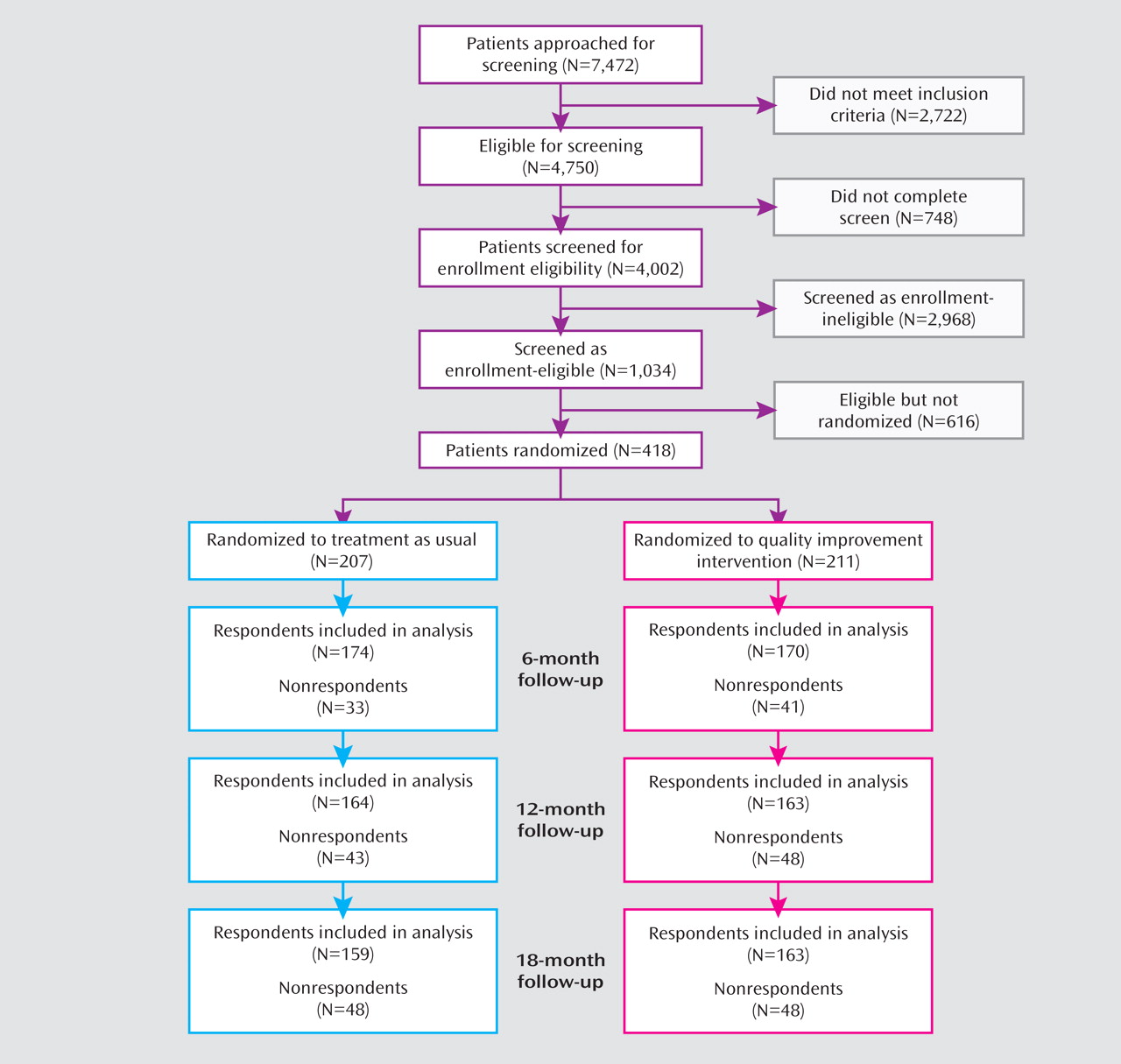

Of 4,750 youths eligible for screening, 4,149 began and 4,002 completed the screening instrument (

Figure 1 ). Of the 1,034 youths who met eligibility criteria, 418 completed baseline assessments and were randomly assigned to the intervention or treatment-as-usual condition. To improve balance across conditions in terms of provider mix and patient sequence, we stratified participants by site and provider. Screening and enrollment staff and assessment staff were blind to randomization status and sequence.

Among the 418 youths enrolled, 380 (90.9%) participated in more than one follow-up evaluation, 344 (82%) participated in the 6-month assessment, 327 (78.2%) participated in the 12-month assessment, and 322 (77.0%) participated in the 18-month assessment (

Figure 1 ). At baseline 178 participants (42.6% of the sample) met CIDI criteria for depressive disorders; the remaining participants reported elevated depressive symptoms but did not meet the threshold for major depression or dysthymic disorder. Rates of baseline depressive disorders were similar for the intervention and treatment-as-usual groups (44% of the intervention group and 41% of the treatment-as-usual group).

Intervention Conditions

Treatment as Usual

Youths in the treatment-as-usual group had access to usual treatment at the site, but not to the specific mental health providers trained in the study CBT and care management services. Treatment as usual was enhanced by providing primary care physicians with 1–2 hours of training

(24) and educational materials (manuals, pocket cards). The training emphasized evaluation strategies, depressive symptoms, common comorbid disorders and complicating conditions, and treatment strategies, particularly medication.

Quality Improvement Intervention

The intervention included 1) expert leader teams at each site to adapt and implement the intervention; 2) clinical care managers who supported providers with patient evaluation, education, pharmacological and psychosocial treatment, and linkage with specialty mental health services; 3) training for care managers in manualized CBT for depression; and 4) patient and provider choice of treatment modalities (CBT, medication, referral, and follow-up). The study informed providers about patient participation only in the intervention condition.

Care managers were psychotherapists with master’s or doctoral degrees in a mental health field or nursing. Spanish-speaking staff were available at two sites, and all other staff were non-Hispanic Caucasians. The study provided a 1-day training session on the study CBT and evaluation-and-treatment model, emphasizing culturally competent care and tailoring the intervention to the cultural context of each patient and family

(25) . It also provided detailed manuals and consultation to support fidelity to the treatment model and provide case-specific training.

Patients in the intervention group—and their parents when appropriate—were offered an in-clinic care manager visit emphasizing evaluation, education about treatment options, and clarification of treatment preferences. A treatment plan was developed, finalized with the primary care provider, and modified when needed. Care managers followed patients for 6 months, supported the primary care provider, and delivered the CBT. The study CBT was based on the Coping With Depression Course

(26,

27), which was developed for individual or group sessions and adapted to enhance feasibility within primary care. This manualized CBT

(26) included an introductory session, three 4-session modules emphasizing different CBT components (activities/social skills, cognitions, communication/problem solving), and a final session emphasizing relapse prevention and follow-up care. The mean number of CBT sessions for patients receiving CBT was 3.85 (SD=3.69; range=1–16), based on case record review

(21) . The Texas Medication Algorithms

(28) guided medication treatment and emphasized selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) as the first-stage medication choice. Further details about the intervention can be found elsewhere

(19,

21) .

Assessment

Assessments were conducted by Battelle Survey Research Institute using computer-assisted telephone interviews and interviewers who were blind to intervention assignment. Continued attempts to contact participants were made until the participant declined to be interviewed or it became clear that he or she could not be reached. Interviewer training and supervision was by staff with official CIDI training. Ratings of interview quality (accuracy in presenting questions, probing, coding) conducted for 10% of interviews indicated good quality (on a 3-point scale with 1 as the highest rating, mean=1.02 [SD=0.06]).

Measures

The primary outcome variable was severe depression, defined on the basis of CES-D score: a score <24 was classified as response, and a score ≥24 (indicating severe depressive symptoms) was classified as nonresponse

(19,

22) .

As a context for understanding the depression outcomes, we also had three secondary outcome variables. We examined mental health-related quality of life using the mental health summary score of the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form–12 health survey

(29) ; satisfaction with care; and process of care (i.e., rates of mental health treatment)

(19) .

Statistical Analyses

For analyses of main intervention effects on outcomes, we followed the intent-to-treat principle. Data for all randomly assigned participants were analyzed according to the experimental arm they were assigned to, regardless of whether patients in the intervention group received treatment or used study resources (such as care management and CBT) or those in the treatment-as-usual group received treatment through usual resources. Repeated-measures analyses were conducted to evaluate intervention effects over time. We fit regression models for continuous outcomes using SAS, version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.) PROC MIXED, and logistic regression models for dichotomous outcomes using SAS GLIMMIX macro, using follow-up data at 6, 12, and 18 months. In the REPEATED statement, we specified autoregressive (AR[1]) covariance structure within subjects to account for the within-subject correlation over time. We treated time as a categorical variable and examined the fixed effects for time, intervention condition, and their interactions with regression adjustment for age, gender, ethnicity, the baseline measure for the same outcome, and study site. To show effect sizes, we present both unadjusted means and proportions by intervention groups and adjusted group differences and odds ratios calculated from the mixed effects models. These analyses were supplemented by a survival analysis examining the impact of the intervention on speed of recovery over the 18-month follow-up period, defined as the first assessment without severe depression (CES-D score <24), while controlling for censoring effects due to differential length of follow-up or recovery in a prior interval. These analyses used an extension of the life table method by the Kaplan-Meier method, as operationalized in SAS PROC LIFETEST. Because intervention effects were predicted to be more likely to occur in the early postintervention period, we tested for between-group differences in survival curves using the Wilcoxon statistic, a nonparametric rank test that more heavily weights earlier events in the survival distribution.

To explore the hypothesis that the intervention might have indirect effects on long-term outcomes, we used path analysis. The path model included a direct path from intervention to severe depression status at 18 months and a direct path from intervention to severe depression status at 6 months, and then to 12 and 18 months, reflecting indirect benefits of the early intervention. The model also included baseline depression, age, gender, ethnicity, and study site as covariates. The path model was estimated using a weighted least squares estimator and the probit link function with Mplus

(30), using procedures recommended by Shrout and Bolger

(31) . Because the path analysis combines analysis of randomized (intervention to 6- or 18-month outcomes) and nonrandomized (depression effects on subsequent depression) effects, it is considered an observational and exploratory analysis.

The criterion we set for statistical significance was a two-sided p value £0.05. We conducted sensitivity analyses by weighting nonresponse

(32) to address missing data for 9% of patients with no follow-up assessments. Nonresponse weights were constructed by fitting logistic regression models to predict follow-up status from baseline clinical and sociodemographic characteristics. Separate models were fitted for each intervention group. The reciprocal of the predicted follow-up probability is used as the nonresponse weight for each participant. For analysis of repeated measures and path analysis, two parallel analyses were conducted with and without nonresponse weighting. Weighted and unweighted analyses yielded similar results. We report results from unweighted analyses.

Results

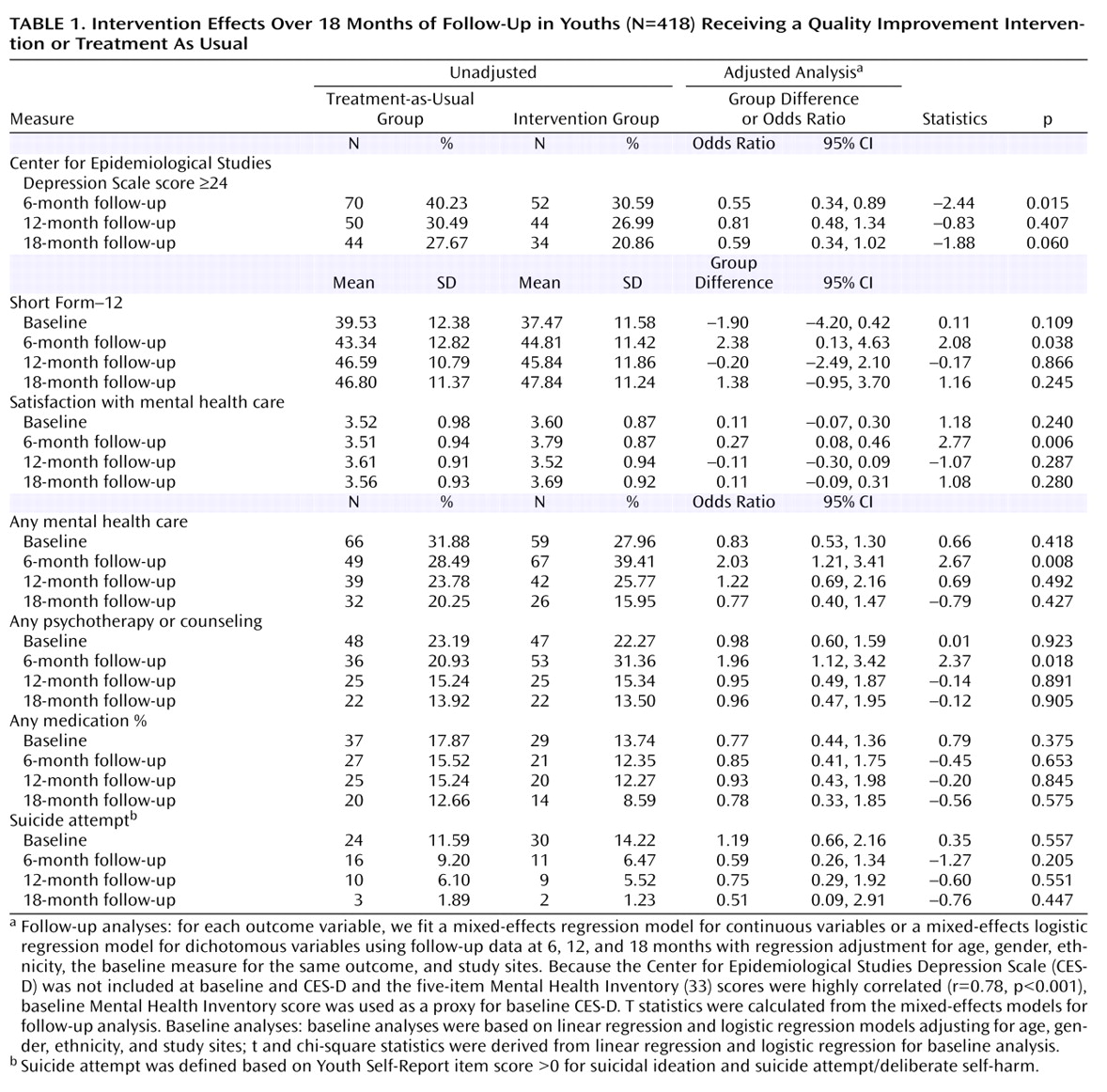

The sample was clinically and sociodemographically diverse. Most patients were female (78%) ethnic minorities (56% Hispanic or Latino; 13% African-American; 1% Asian; 17% other or mixed ethnicity). The sample included patients with depressive disorders (43%), primarily major depression (42%), and patients with subsyndromal depression (57%). There were no significant differences between the quality improvement and treatment-as-usual groups at baseline (see

Table 1 ). The statistical analysis strategy differed in this paper from that used in the 6-month outcome paper

(19) ; the results are similar but differ slightly in numerical value.

Main Intervention Effects

Results of mixed-model analyses (

Table 1 ) confirmed significant intervention effects on rates of severe depression at 6 months. The trend toward decreased rates of severe depression in the intervention compared with the treatment-as-usual group at 18 months did not reach statistical significance (p=0.06). Intervention effects on secondary outcomes (Short Form–12 mental health summary, satisfaction with care, rates of mental health treatment) were statistically significant only at the 6-month outcome point. Sensitivity analyses using the continuous CES-D score revealed statistically significant intervention effects only at 6 months. The study did not have sufficient statistical power to assess suicide attempt outcomes, and there were no statistically significant intervention effects on rates of suicidal ideation or suicide attempt. Attempt rates declined >50% in the intervention group at 6 months, but also declined in the treatment-as-usual group (

Table 1 ).

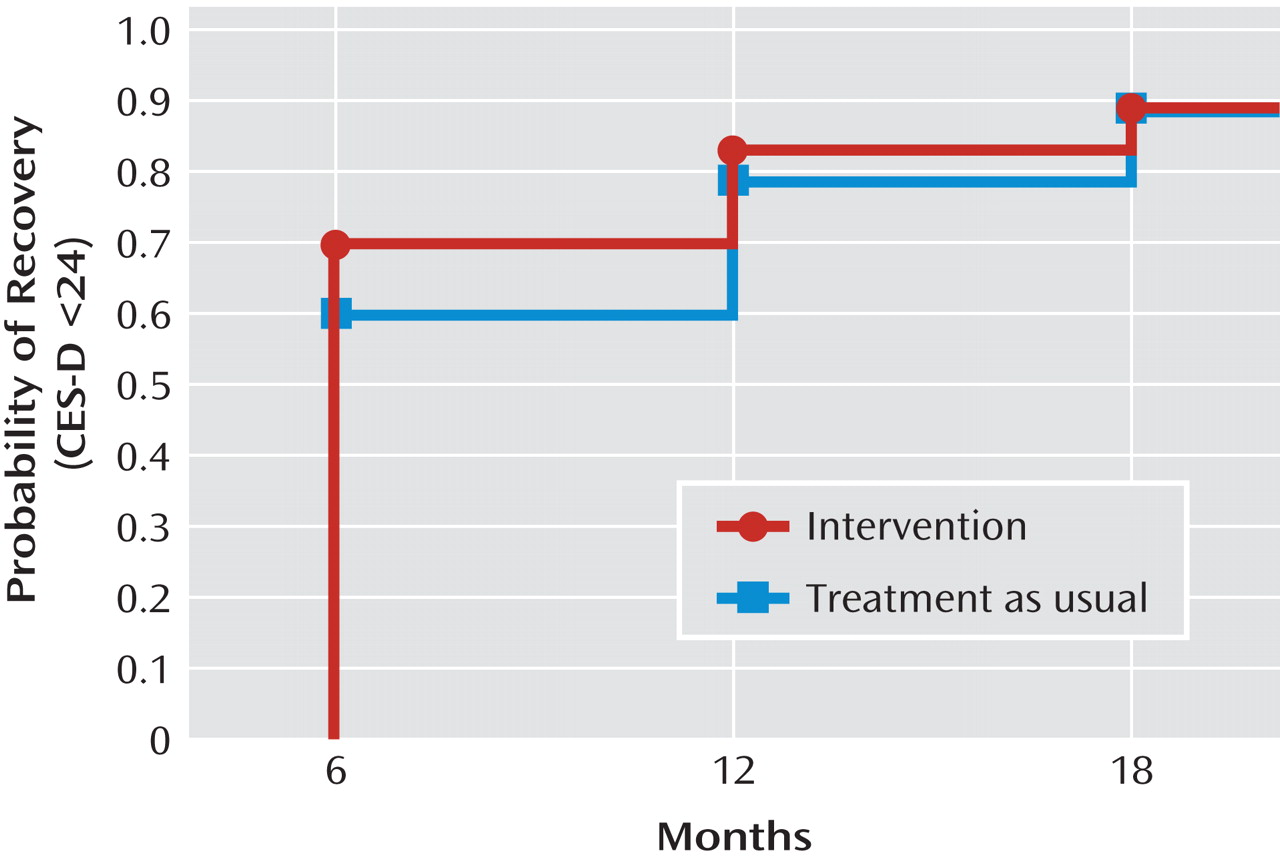

Figure 2 shows time to first recovery (CES-D score <24) over 18 months. The Kaplan-Meier survival analysis showed that the between-group difference in the estimated probability of initial recovery was roughly 10 percentage points at 6 months, 5 percentage points at 12 months, and zero at 18 months, with a 90% cumulative probability of recovery in each group over the 18-month follow-up period. Mean times to recovery were 8.76 months (SD=0.35) for the intervention group and 9.65 months (SD=0.37) for the treatment-as-usual group, suggesting a first recovery almost 1 month (27 days) earlier in the intervention group. Statistically significant between-group differences were seen only at 6 months (z=2.03, p=0.042). The overall trend toward faster recovery for the intervention group compared with the treatment-as-usual group over 18 months did not reach statistical significance (Wilcoxon χ

2 =3.60, p=0.058).

Indirect Intervention Effects

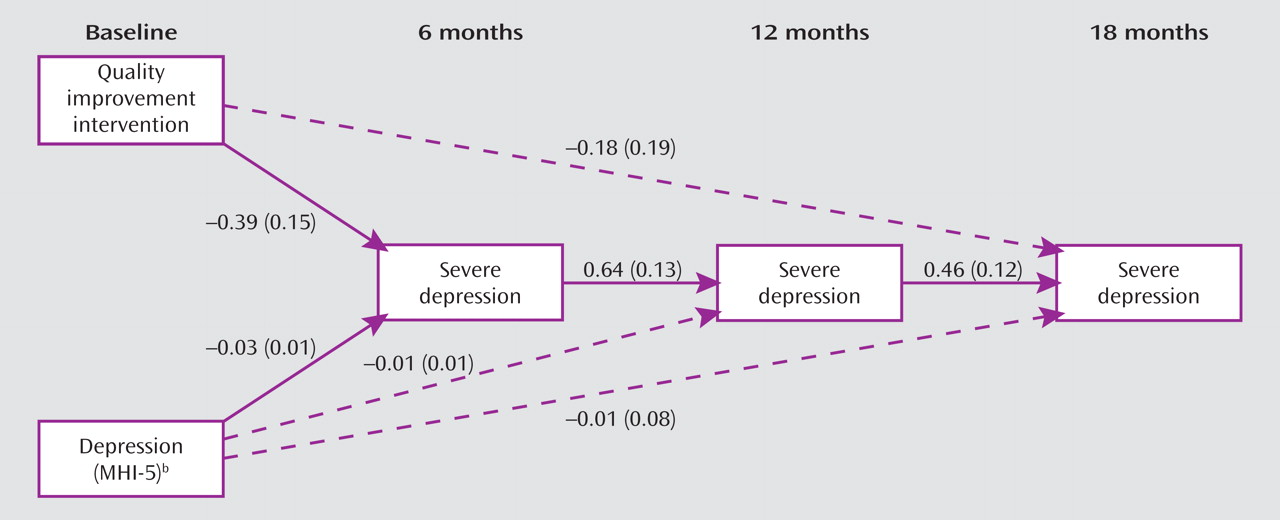

Figure 3 presents the path analysis model graphically, with probit models specified for the dichotomous outcome variable (severe depression) at three outcome time points (months 6, 12, and 18). Estimated coefficients and standard errors of the probit model are displayed for each significant path, depicted by a solid line; dashed lines show nonsignificant paths that were included in the model specification. For parsimony, the baseline covariates included in the model are not depicted. The direct effect of the intervention on 18-month outcome was not significant, although the indirect path specified was (t=–2.21, p=0.027), as were all of the paths within that indirect path: the effect of the intervention on 6-month depression (t=–2.57, p=0.011); the effect of 6-month depression on 12-month depression (t=4.91, p<0.001); and the effect of 12-month depression on 18-month depression (t=3.83, p<0.001). Sensitivity analyses replicated the path model using CES-D score (indirect effect: t=–2.29, p=0.023) and the secondary outcome of mental health-related quality of life (Short Form–12 mental health summary) (indirect effect: t=2.29, p=0.023), showing replication of findings across different outcome variables.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate a quality improvement intervention for depressed youths in primary care settings. We found that the intervention, relative to treatment as usual enhanced by provider training, led to more rapid recovery—specifically, to a reduced likelihood of severe depression 6 months after the intervention. Over an 18-month follow-up period, we observed a significant indirect intervention effect on rates of severe depression, depressive symptoms, and mental health-related quality of life. This finding suggests a continuing advantage for youths in the intervention group resulting from the initial clinical benefit of the intervention at 6 months, which then shifted youths toward a healthier path through 12 and 18 months. This may have occurred, for example, through a lowering of the risk for chronic or recurrent depression conferred by the initial clinical improvement. We found no support for a purely direct intervention effect on long-term outcomes, such as might have resulted from continuing differences in use of treatments or continuing application of strategies learned in CBT.

These results must be viewed in the context of the study limitations. Our sample size (N=418) was considerably smaller than the adult (N=1,356) and late-life depression (N=1,801) studies

(11,

34), resulting in less statistical power to detect intervention effects. Given the high rates of recovery in youth depression and low levels of treatment received (particularly medication) relative to efficacy studies, a larger study is needed to replicate and further explain the indirect pathway findings or to observe small main effects. We also do not have data on longer-term outcomes allowing us to identify differences in relapse rates over several years. Other important limitations include selection of particular sites, moderate response rates, reliance on self-report measures, and the more exploratory nature of the causal modeling for indirect effects.

To our knowledge, only two prior studies have reported on the impact of depression treatment among adolescent primary care samples. Mufson et al.

(35) demonstrated short-term (12-week) effects of a controlled trial of interpersonal psychotherapy delivered in school-based health clinics. Clarke et al.

(36) found a marginal advantage for a 9-month collaborative care CBT program delivered in combination with “usual” SSRI medication compared with SSRI treatment alone; in an assessment of the program impact over 12 months, the strongest impact appeared to be between 6 and 9 months. Our findings are consistent with results of these studies in emphasizing the salience of early intervention effects as the main effects. We would expect weaker effects in Youth Partners in Care because of our emphasis on effectiveness with treatment delivered under “usual” treatment conditions, in which patients chose their preferred treatments (including no treatment), and treatment rates were lower relative to these other studies. In a study such as ours, even small main effects are of interest because they would suggest that strategies to further increase treatment utilization might further improve outcomes.

In the adult Partners in Care study and a study of similar quality improvement interventions for depressed elderly patients, outcome improvements were observed through 2 years, and for some groups, such as ethnic minorities and those with subthreshold depression, through 5 years and beyond

(8,

34,

37 –

40) . The Partners in Care study reported indirect intervention effects that continued through 5 years and led to both improved health and life event outcomes

(39) . The intervention effect sizes at 6 months looked similar for Partners in Care and Youth Partners in Care. Because of methodological differences, including in the measures used and in sample size, we cannot be confident that the youth intervention has smaller effect sizes at 18 months, but effect sizes do appear to be smaller at 12 months. Future research should focus on developing strategies to strengthen longer-term outcomes, such as finding ways to reinforce key information and access to resources for depression care as youths transition through different life roles and health care service delivery pathways. Because of relatively high natural recovery rates for youth depression, considerably larger samples (two to three times larger than in this study) will probably be needed to confidently determine the magnitude of any long-term outcome effects.

The results of this study reinforce the finding that quality improvement programs for youth depression improve clinical outcomes at 6 months, or by the end of the active intervention period, and shorten time to recovery within the first 6 months. They also suggest that such programs constitute an investment in the future health of youths by exerting a favorable effect on their course over the longer term through initial intervention effects. Although this finding must be replicated, it suggests an important direction for new research on improving outcomes for youth depression. It also may be encouraging to providers and families that their efforts to deliver and receive evidence-based depression care for youths may have longer-term, indirect benefits. The finding also supports the value of a more proactive effort to identify and support access to treatment for depressed youths in primary care and is generally consistent with the recent recommendations from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force to screen adolescents for major depression when resources are adequate for evaluation, treatment, and follow-up

(41) .