However, more recent reports have identified a higher than expected risk of fetal death/stillbirth or neonatal death (

5–

12) and infant mortality (

5–

8,

11) in offspring of parents with mental illness. The reasons for these inconsistent findings over time very likely include the use of obsolete methods and inadequate sample sizes, as well as the selection process, in earlier studies. The studies based on the best available evidence to date are those that used data from large-scale registries in Denmark (

5,

11), Sweden (

8), and Australia (

13). Except for the Australian study, which found no increased mortality risk, most of these studies identified a risk of stillbirth and perinatal and infant mortality approximately twice as high in offspring of parents with severe mental illness relative to unexposed offspring. A meta-analysis performed by Webb et al. (

2) also indicated a doubling of stillbirth/fetal death risk in offspring exposed to maternal psychotic disorder.

An elevated mortality risk was also reported for exposed offspring beyond infancy to early adulthood (

11), with an even higher risk of dying of unnatural causes, such as homicide during childhood and suicide in early adulthood (

14). Despite these limited findings, evidence on cause-specific mortality risk in exposed offspring beyond the first year of life remains sparse. Moreover, Asian and Western psychiatry possess differing, complex histories of development, leading to significant differences in sociocultural circumstances for the mentally ill. For example, in Asia, there is a more profound stigma associated with mental illness and far less acceptance of counseling and psychotherapy compared with medication, and there are potentially differential thresholds for defining psychiatric symptoms in Asian as compared with Western societies (

15–

17). All studies to date linking parental mental illness and mortality risk in offspring were conducted in Western countries; no similar evidence has been evaluated in Asia.

The objective of this nationwide population-based study was to investigate mortality risk in preschool children (up to age 5) of parents with schizophrenia and affective disorders in Taiwan. The risks of both natural and unnatural causes of death were examined separately. We followed mortality in exposed offspring for 5 years because in Taiwan, the 9 years of compulsory education starts at age 6; offspring exposed to parental mental illness are more vulnerable to quality of care issues and domestic hazards during their preschool years.

Method

The study linked three nationwide population-based data sets. The first data set was drawn from the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD). Taiwan began its National Health Insurance (NHI) program in 1995 to provide affordable health care for all residents of the island. The NHIRD covers all inpatient and outpatient medical benefit claims for Taiwan's population of over 23 million, representing over 98% of its population. The NHIRD also includes a registry of contracted medical facilities, a registry of board-certified physicians, and details of inpatient orders and expenditures on prescriptions dispensed at contracted pharmacies.

The second data set used was the Taiwan birth certificate registry, which contains sociodemographic information, such as parental age and education, on all births occurring in Taiwan. The third data set was the Taiwan death certificate database. Since it is mandatory to register all births, deaths, marriages, divorces, and migrations, birth and death certificate data in Taiwan are considered highly accurate and complete.

The mother's and infant's unique personal identification numbers provided links between the NHIRD, birth certificate, and death certificate data, with assistance from the Bureau of NHI in Taiwan. Since the registration of all births is mandatory in Taiwan, the mother-offspring linkage has been almost complete. We might lack fatherhood data in approximately 0.3% of infants because of a very low rate (about 3% in 2001) of single motherhood in Taiwan (

18). Confidentiality assurances were addressed by abiding by the data regulations of the Bureau of NHI. The Bureau encrypted all personal identifiers. Since the NHIRD consists of de-identified secondary data released to the public for research purposes, this study was exempt from full review by the institutional review board.

Study Sample

A total of 473,529 women who had live singleton births between January 1, 2001, and December 31, 2003, fulfilled our initial selection criteria. If a woman had more than one singleton birth during the study period, we selected only the first one for our study sample. Of these births, we identified 3,166 individuals whose parents had serious mental illness (mother, father, or both with a principal diagnosis of schizophrenia [ICD-9-CM code 295] or affective disorder [ICD-9-CM code 296] occurring in an inpatient setting or appearing in two or more ambulatory care claims coded within the 2 years preceding their index deliveries).

The sample for the comparison cohort was drawn from the remaining 470,363 births. We randomly selected 25,328 births (eight for every birth to parents with serious mental illness) matched with the study group in terms of maternal age (<20, 20–24, 25–29, 30–34 and ≥35 years) and year of delivery. Ultimately, 28,494 singleton live births fulfilled our criteria and were included in our study. Each child was individually tracked for a 5-year period from its delivery between 2001 and 2003 until the end of 2008 to distinguish all who died during that time. We categorized all deaths as having occurred from natural or unnatural causes; unnatural causes were suicides, accidents, and homicides, and all other deaths were defined as due to natural causes.

Statistical Analysis

The SAS statistical package (SAS System for Windows, version 8.2) was used to perform all analyses. The 5-year cumulative survival estimates and survival curves for the two cohorts were calculated by the Kaplan-Meier method, with the log-rank test being used to examine differences between cohorts. Cox proportional hazard regressions were carried out as a means of computing the adjusted 5-year survival rate. The regression modeling also adjusted for maternal age, highest maternal education level, maternal medical comorbidities, infant's gender, parity, and low birth weight status, as well as family monthly income and parental age difference. Finally, we computed hazard ratios along with the 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) using a significance threshold of 0.05.

Results

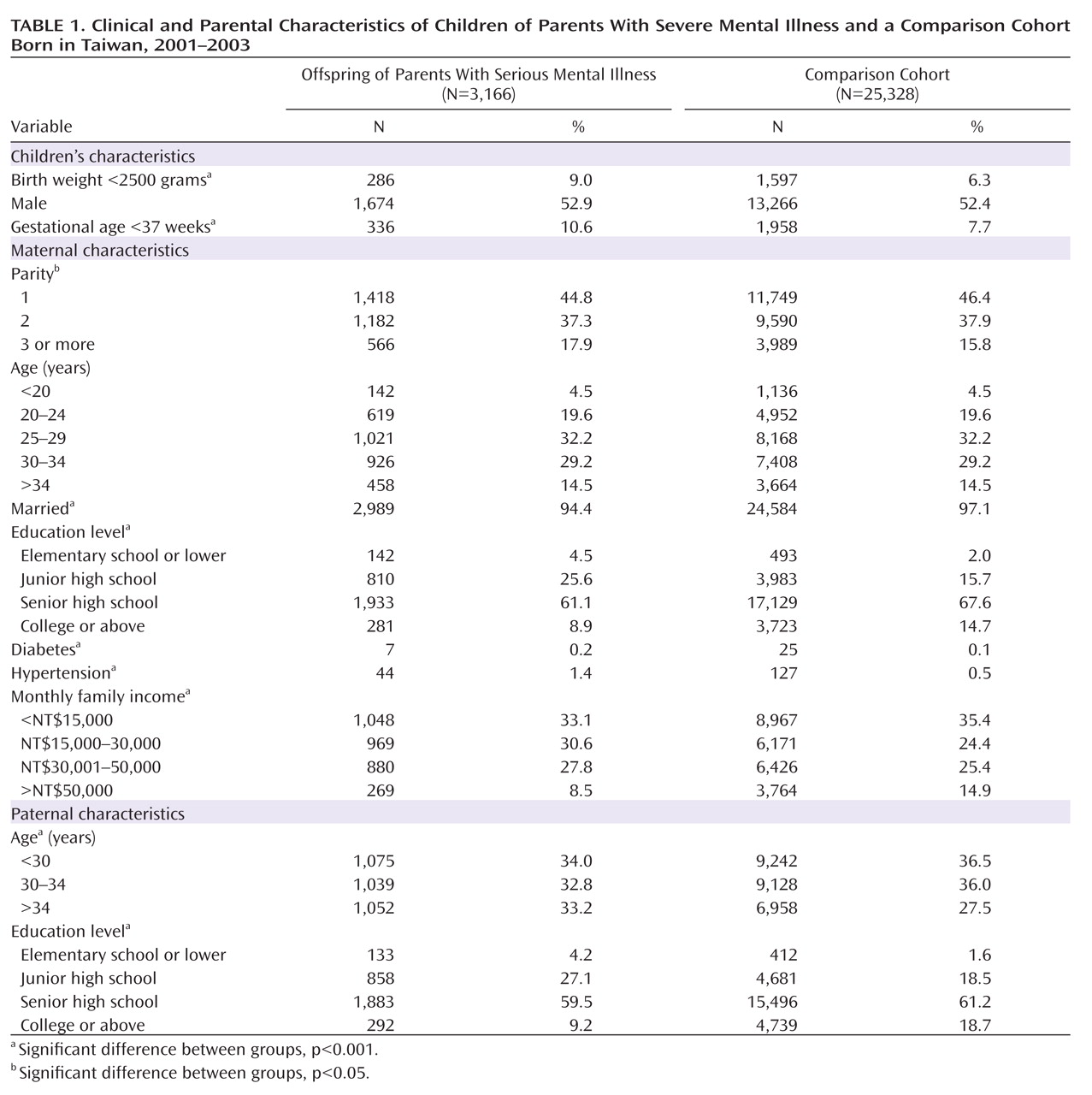

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of infants and mothers for the sampled births by cohort. Relative to offspring in the comparison cohort, offspring of parents with serious mental illness were more likely to have low birth weight and preterm birth. Their mothers were more likely to have diabetes and hypertension and to be unmarried, and on average they had a lower education level than mothers in the comparison cohort. The fathers on average were older and had a lower education level than fathers in the comparison cohort.

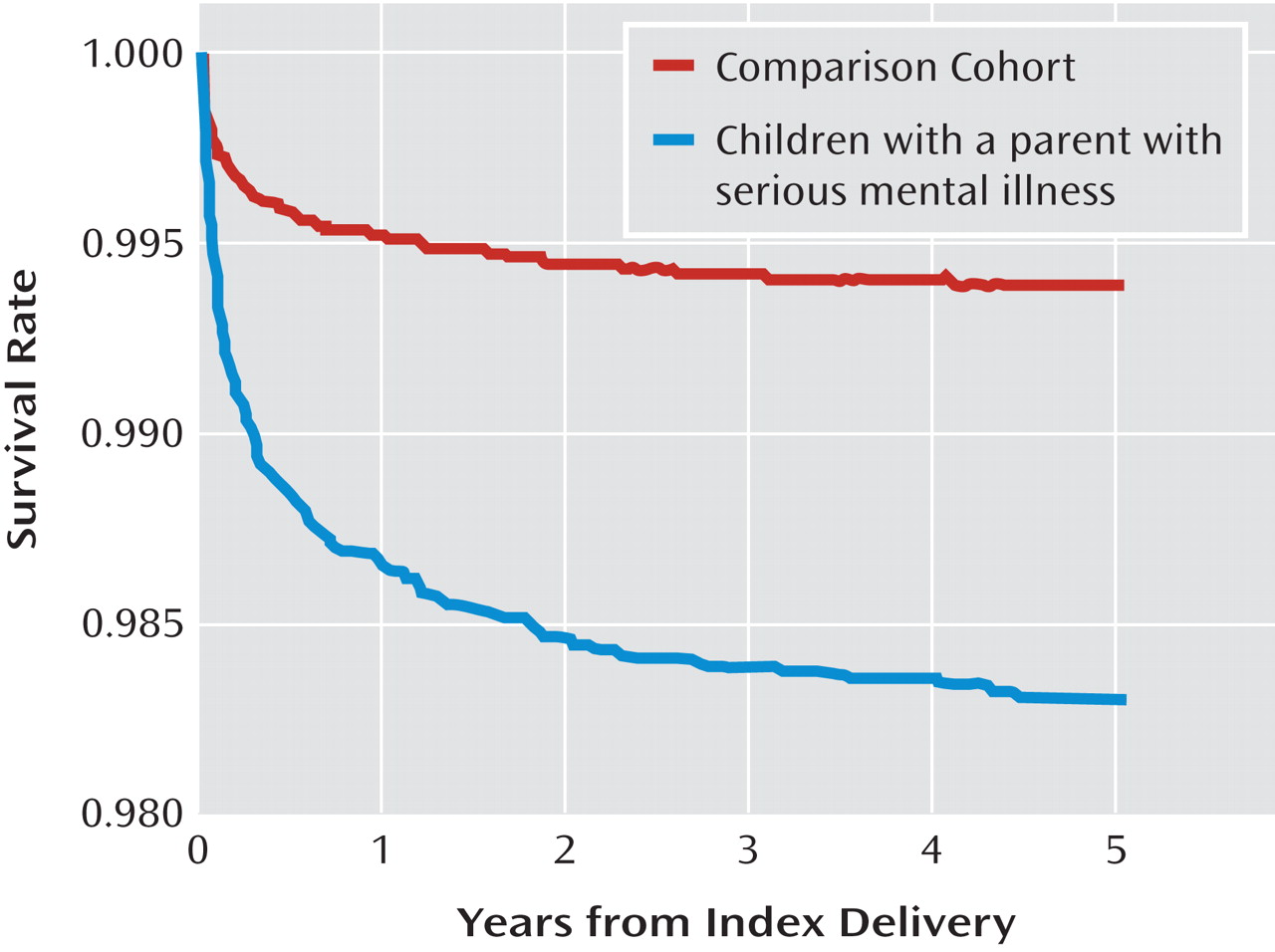

Of the total birth sample of 28,494 offspring, 209 (0.73%) died during the 5-year follow-up period, 54 (1.7%) from the study cohort and 155 (0.6%) from the comparison cohort. The log-rank test indicated that the 5-year survival rate was significantly lower for the offspring of parents with serious mental illness than for children in the comparison cohort (p<0.001). The results of the Kaplan-Meier survival analysis are presented in

Figure 1.

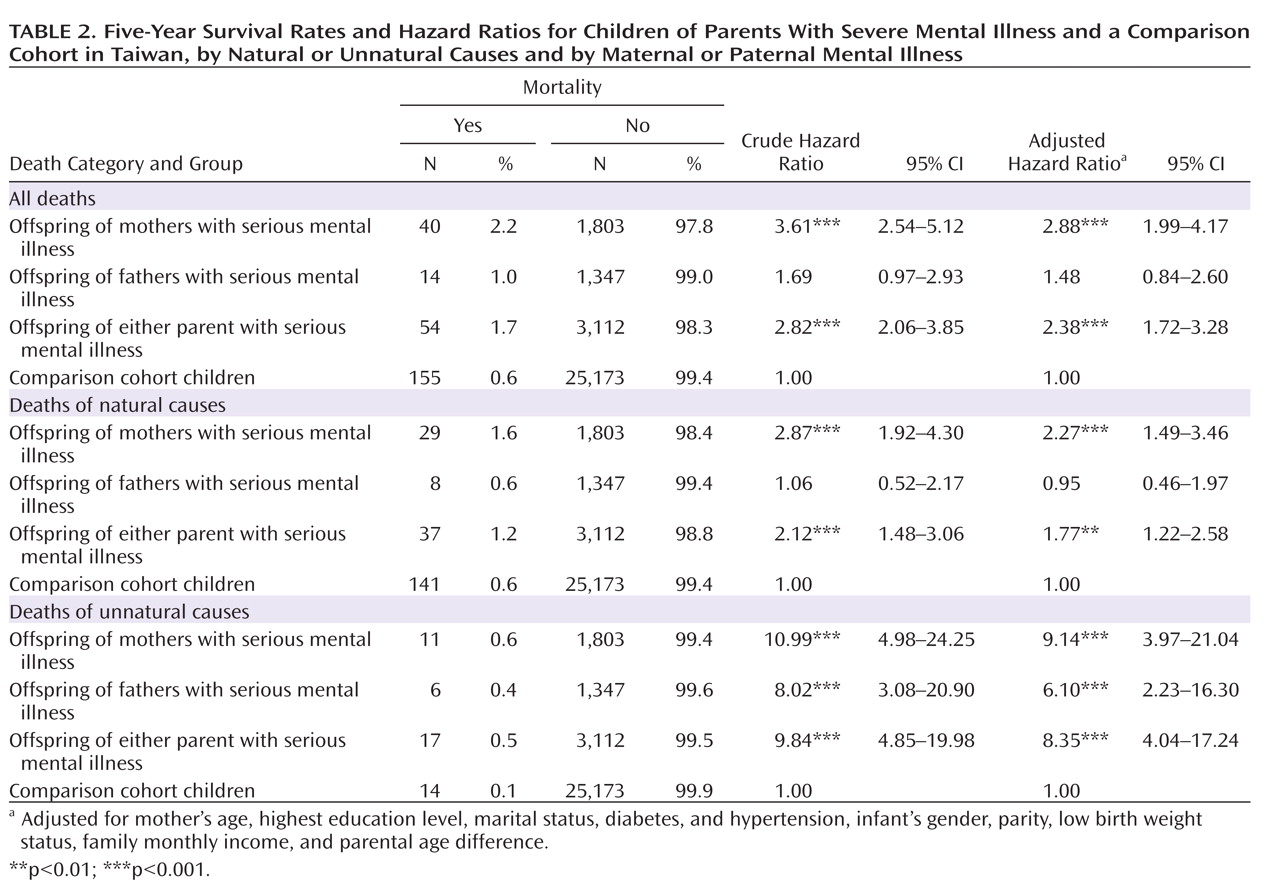

Table 2 presents the 5-year survival rate, crude hazard ratios, and adjusted hazard ratios of mortality for two cohorts stratified by mother with serious mental illness, father with serious mental illness, and either parent with serious mental illness. For the offspring of parents with serious mental illness, the hazard ratio of dying during the 5-year follow-up period was 2.82 (95% CI=2.06–3.85, p<0.001) compared with children in the comparison cohort. After adjustment for maternal age, highest maternal education level, maternal marital status, maternal diabetes, maternal hypertension, infant gender, parity, and birth weight status, as well as family monthly income and parental age difference, the risk of dying during the follow-up period, relative to children in the comparison cohort, was 2.88 (95% CI=1.99–4.17, p<0.001) for offspring of mothers with serious mental illness and 2.38 (95% CI=1.72–3.28, p<0.001) for offspring with either parent with serious mental illness.

Surprisingly, the adjusted hazard ratio for dying of unnatural causes during the 5-year follow-up period was, for offspring of mothers with serious mental illness, 9.14 (95% CI=3.97–21.04, p<0.001); for offspring of fathers with serious mental illness, 6.10 (95% CI=2.23–16.30, p<0.001); and for offspring of either parent with serious mental illness, 8.35 (95% CI=4.04–17.24, p<0.001) relative to children in the comparison cohort. The adjusted hazard ratio for dying of natural causes during the 5-year follow-up period was only 1.77 (95% CI=1.22–2.58, p<0.01) relative to children in the comparison cohort.

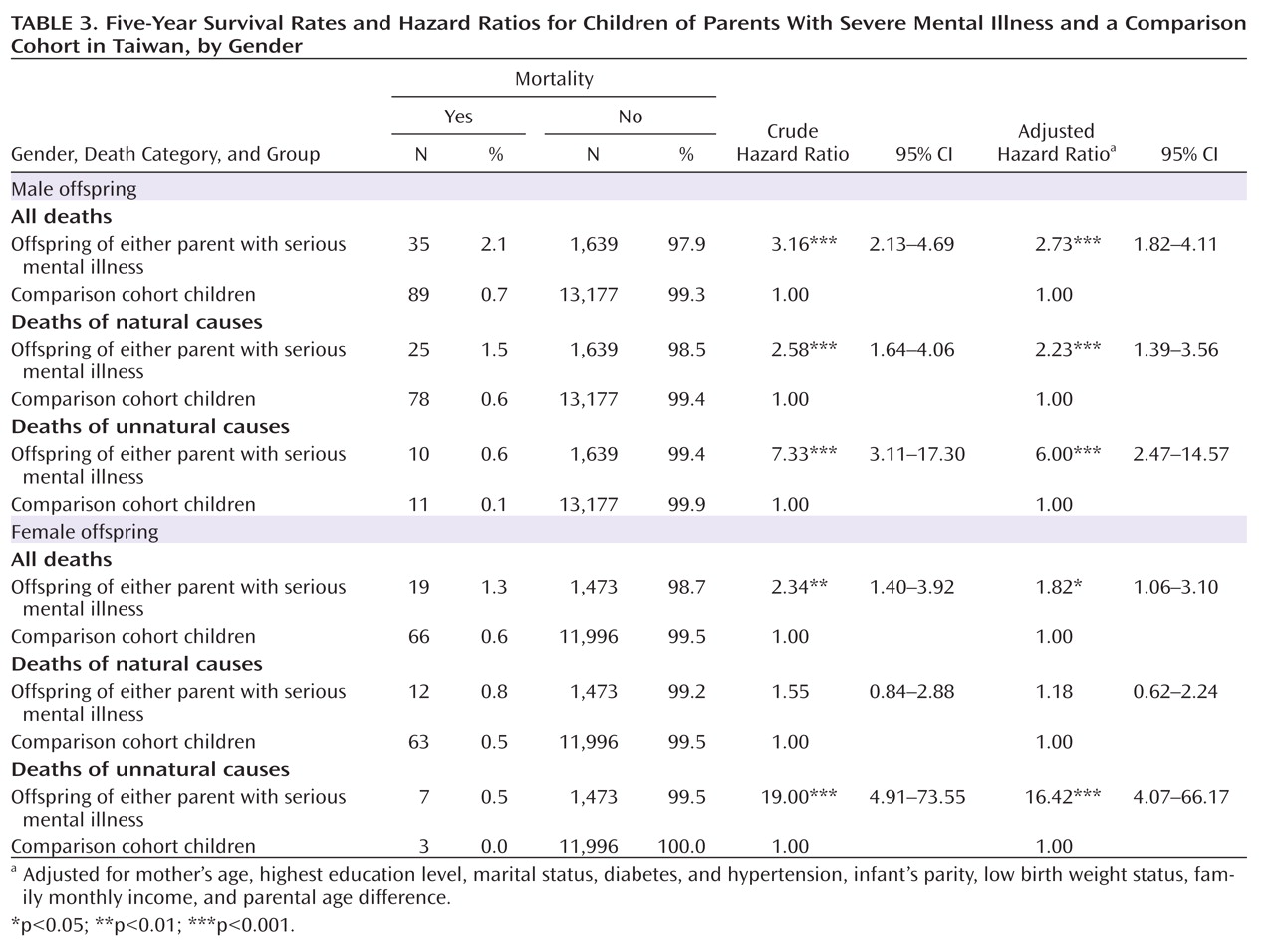

Table 3 lists 5-year mortality risks stratified by offspring gender. For male offspring with either parent with serious mental illness, adjusted hazard ratios for death from all causes, natural causes, and unnatural causes during the preschool years were 2.73, 2.23, and 6.0, respectively, relative to offspring in the comparison cohort. For female offspring, the adjusted hazard ratios were 1.82 and 16.42 for all causes and unnatural causes of death, respectively.

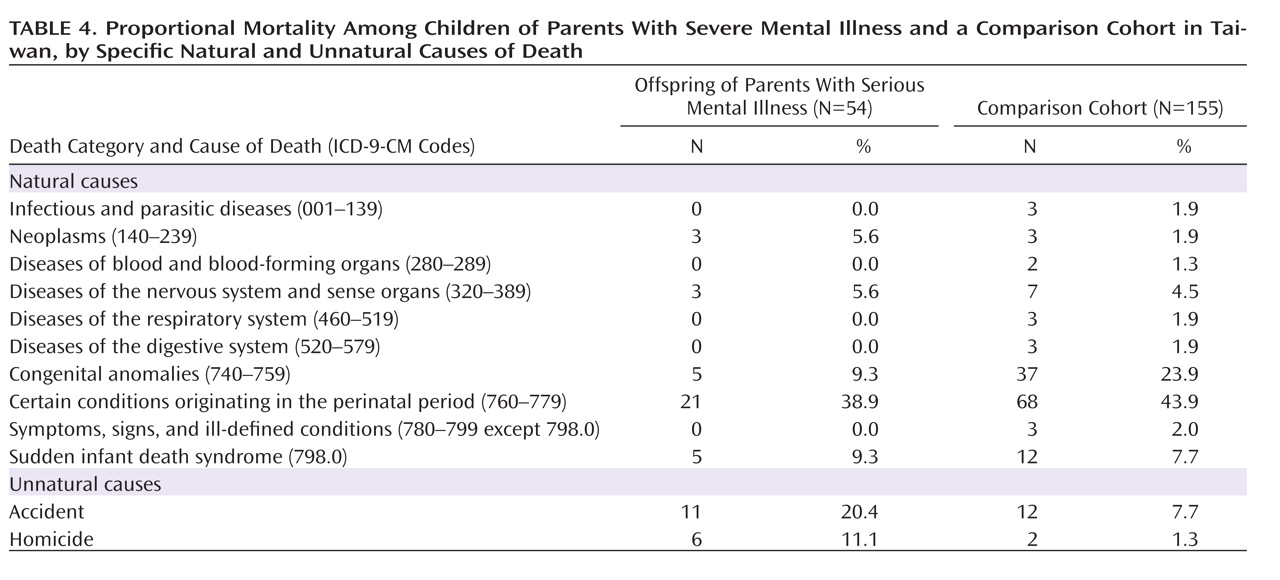

Table 4 lists the proportional mortality by specific cause of death within the broader categories of natural and unnatural causes. Among all children who died, more than 20% and 11% of those of parents with serious mental illness died of accidents and homicide, respectively. In comparison, only 7.7% and 1.3% of deceased children in the comparison cohort died of accidents and homicide, respectively. We also found that the hazard ratio for dying of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) was 3.34 (95% CI=1.18–9.48, p<0.001) for offspring of either parent with serious mental illness relative to children in the comparison cohort (data not shown in table).

We further analyzed the hazard ratios for accidental death and homicide separately (see the data supplement that accompanies the online edition of this article). Since there were only two homicide cases in the comparison cohort, which precluded estimation of a precise hazard ratio for that outcome, we used all live singleton births between January 1, 2001, and December 31, 2003 (except for those whose parents had serious mental illness, as the comparison cohort), to calculate a hazard ratio. The adjusted hazard ratio of suffering an accidental death during the 5-year follow-up period was 3.65 (95% CI=1.99–6.66, p<0.001), and of suffering a homicide, 19.41 (95% CI=8.23–45.80, p<0.001) for offspring of parents with serious mental illness relative to children in the comparison cohort. It should be noted, however, that the 95% confidence intervals for these hazard ratios were wide, especially for homicides.

Discussion

This is the first population-based report of an increased mortality risk in children of psychiatric patients in an Asian society. During a 5-year follow-up of 3,166 children with at least one parent with a serious mental illness and a comparison cohort of 25,328 children, 54 (1.7%) deaths were documented among children of parents with mental illness and 155 (0.6%) in the comparison cohort. For offspring up to 5 years of age, exposure to parental mental illness was independently associated with a risk of death nearly 2.4 times greater than for children in the comparison cohort after adjustment for sociodemographic characteristics and maternal comorbidities. The association was even more marked when only unnatural causes of death were considered; mortality among children of affected parents was more than eight times higher than among children in the comparison cohort. The proportional mortality was as high as 20.4% for accidental death and 11.1% for homicide among offspring exposed to parental mental illness.

In the body of literature linking parental psychopathology to offspring mortality risk, the most recent population-based studies using the best available evidence to date have documented an increased risk of death for exposed offspring. In Denmark, Webb et al. (

11) reported an increased mortality risk for exposed offspring from birth through early adulthood, with milder risk observed during years of school attendance. Bennedsen et al. (

5) likewise observed an elevated risk of postneonatal mortality among children whose mothers had schizophrenia. In Sweden, Nilsson et al. (

8) found higher risks of stillbirth and infant death among offspring of mothers with schizophrenia.

Our study extended these Scandinavian findings to an Asian society, Taiwan, finding that offspring of parents with schizophrenia and affective disorders experience significantly more than twice the risk of dying during their preschool years. Furthermore, mortality risks were generally higher among offspring with maternal mental illness than for those with paternal mental disease.

In assessing unnatural causes of death, Webb et al. (

14) found that the relative risk of homicide was 6.18 for offspring of mothers with mental illness and 9.8 for offspring of fathers with mental illness. Indeed, the most remarkable finding in our study was the significantly elevated hazard ratio (8.35) for death by unnatural causes among exposed offspring, with specifically higher proportions of mortality by homicide (11.1% among exposed offspring compared with 1.3% in the comparison cohort) and accidents (20.4% among exposed offspring compared with 7.7% in the comparison cohort). As previously reported (

19), Chinese parents generally use harsher parenting discipline and show higher rates of severe violence toward children compared with U.S. parents. One U.S. study found that among young children, the assailant in homicides was usually a parent (

20). Thus, offspring of parents suffering from stress or psychiatric illness might be under greater threat of mistreatment or even unexpected death. By stratifying by parent gender, we found a higher risk of dying from unnatural causes among children whose mothers had severe mental illness than among children whose fathers had severe mental illness. Indeed, previous studies have identified female caregivers as the most likely abusers of children (

19,

21). Furthermore, despite the rather wide confidence intervals, girls appeared to have a greater risk of unnatural death than did boys. Even with social changes and modernization, most parents in traditional Chinese families still prefer sons to daughters. Girls might thus endure more emotional and physical mistreatment from their parents.

Two Danish studies of national cohorts showed an increased risk of SIDS among infants with either maternal or paternal psychiatric illness (

5,

22). Comparably, in our Taiwanese data, exposure to parental mental illness was independently associated with a risk of SIDS 3.3 times higher than for children in the comparison cohort. Although complicated factors might be involved, parental psychiatric disorders, such as maternal perinatal depression and paternal affective disorder, might be risk factors for SIDS (

22–

25). Uncertainty also arises from the difficulty in distinguishing SIDS from covert homicide (

26).

Parents with psychiatric illness are associated with numerous factors that pose mortality risks for their offspring. First, significant excess risks in pregnancy such as birth complications, low birth weight, and poor neonatal condition have been documented in this population in a meta-analysis (

27) and in recent population-based studies (

5,

8,

13). Such adverse circumstances at birth may be associated with subsequent mortality risks from infancy through young childhood. Second, psychiatric patients are a disadvantaged group on average, with lower socioeconomic status and deprived or problematic domestic environments (

28,

29). Socioeconomic adversity resulting from psychiatric illness can have a detrimental influence on health, posing an increased mortality risk for offspring (

30). Third, psychiatric diseases can impair a person's competence to parent adequately. A compromised ability to provide direct care and intimate interaction with offspring could cause parent-child detachment and, ultimately, maltreatment (

31,

32). The acquisition of parenting skills may also be impeded by cognitive deficits that accompany some mental illnesses (

33,

34). Being ill-equipped for parenting, patients with psychiatric illness may hold more negative views of their infants and are more likely to report physical harm or emotional neglect of their children (

35). Accordingly, exposed children are more likely to experience poor developmental outcomes. Finally, women with mental illness have an elevated risk of inadequate antenatal and postnatal health care for their offspring (

36). Children of psychiatric patients may also lack prompt and necessary medical care. A higher mortality risk for exposed offspring may thus be linked to insufficient health service utilization (

37).

There are significant implications to this study. Preventive programs targeting socioeconomic adversity for early detection of vulnerable families and appropriate treatment of psychiatric illness may be beneficial for decreasing mortality risks to offspring of parents with severe mental illness. The clinical setting should ideally have a multidisciplinary team approach that provides obstetric and psychiatric care as well as psychological and social work services, since family stability and access to social and financial resources is associated, to some extent, with improved parenting (

35). The notably high risk of death by unnatural causes among exposed offspring, especially homicide, highlights the critical consequences of disregarding inadequate child care practices adopted by parents with severe mental illness. An urgent need for professional involvement and risk management strategizing to support psychiatric patients who have difficulty with their transition to parenthood is clear.

Our study leads the way toward examining the risk of death by both natural and unnatural causes among preschool children of parents with severe mental disorders in an Asian society, Taiwan. Using nationwide population-based data sets, we were able to use a large sample that was largely exempt from selection and nonresponse bias. Moreover, almost all recent register-based large-scale studies investigating mortality risks among offspring of psychiatric patients declare as a limitation the inability to adjust for the potentially important confounder of socioeconomic status (

5,

11,

14). In our study, the monthly family income and the highest maternal education level, proxies for socioeconomic status, were adequately controlled.

Three limitations of this study merit attention. First, our sample included only patients who sought treatment for their psychiatric illness in an inpatient or ambulatory care setting. It is possible that factors such as social stigma and economic circumstances would lead some individuals with mental illness not to seek or to refuse medical care. The observed hazard ratios in our study might thus be attenuated. Second, despite the use of large nationwide data sets, the small overall number of deaths among offspring of psychiatric patients precluded calculation of a precise estimation of the effects of specific causes of death and effects stratified by gender of parent and offspring separately. The rather large confidence intervals observed in some estimations must be considered in appropriately interpreting the results. Third, we were unable in this study to investigate the effects of risk factors such as fewer antenatal visits, maternal smoking, prescription medications, and substance use during pregnancy. However, low birth weight, which partially reflects these risk factors and is closely connected with the future growth and mortality risk of offspring, was adequately considered in the adjusted models in our study.

Our study highlights the importance of early recognition, appropriate treatment of parental psychiatric illness, and adequate support and supervision of vulnerable families to ultimately reduce mortality risk in offspring during the preschool years. Identifying causal mechanisms specific to the children's age and risks resulting from maternal and paternal vulnerability is needed in future studies.