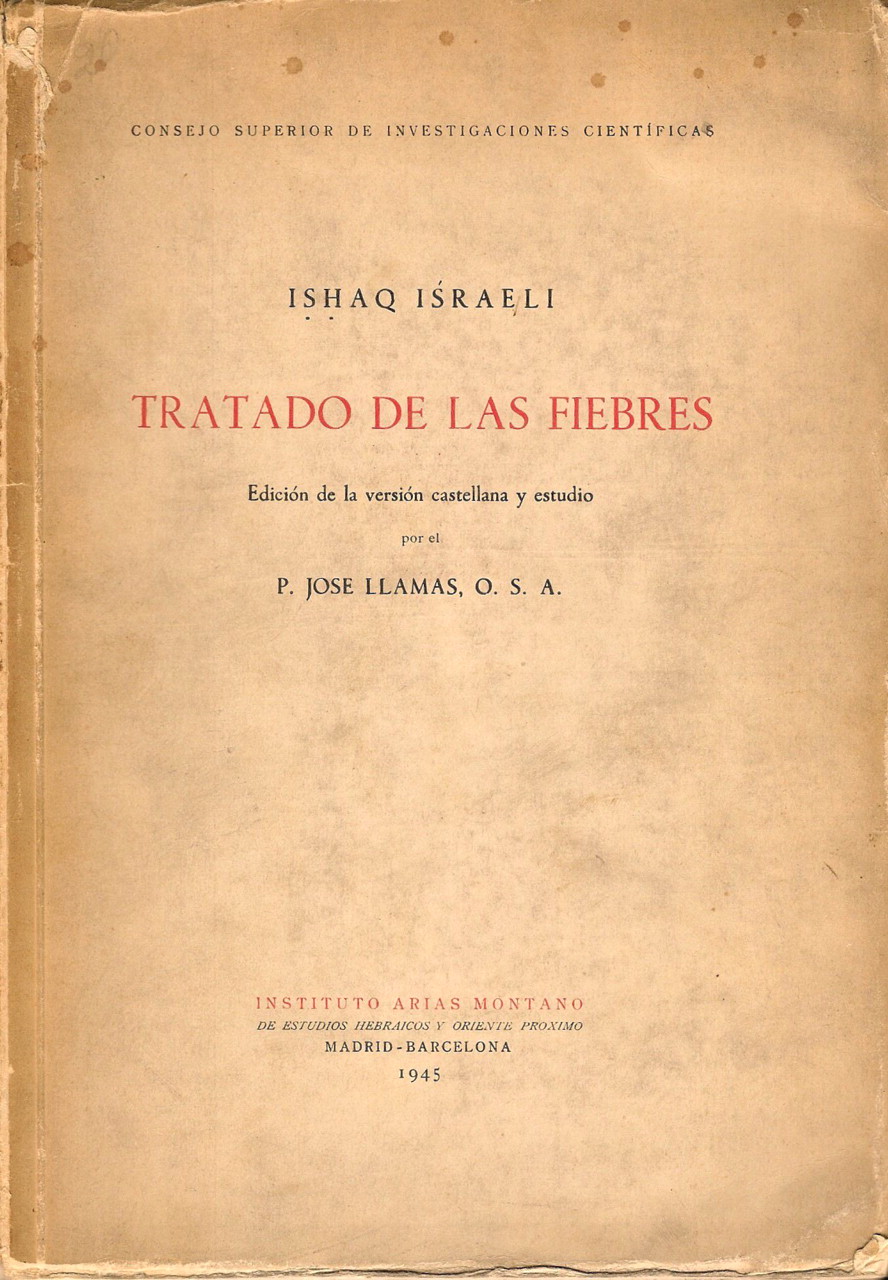

In the 1920s a scholarly Augustine monk discovered the only known translation into (medieval) Spanish of Ishaq ben Sulayman al-Israeli's

Treatise of Fevers (

1), which was mandatory reading in European universities throughout the Middle Ages (

2,

3).

This book, written originally in Arabic in the 11th century, is part of the large oeuvre of one of the most influential physicians and philosophers of the golden period of Arab medicine, contemporaneous and occasional interlocutor of the other great Jewish physician of his time, Moses Maimonides.

Chapter XI of the second book of the

Treatise of Fevers, titled "Treatise on the ephemeral fever that derives from reasons of sorrow" (

1, pp. 53–55), contains a foray of al-Israeli into the field of psychopathology. In it he differentiates

sadness, "lodged in reason" and characterized by lethargy, from

sorrow, "lodged in emotions" and characterized by agitation and lack of appetite—a distinction that fits what we would currently call "psychomotor retardation" and "psychomotor agitation." The chapter closes with a set of therapeutic recommendations (translated from medieval Spanish by the author):

It is necessary that we start...finding ingenious ways of eliminating suspicions, and caring for the soul...with many types of musical songs...and all those things that bring joy and would help to forget the sadness....

Aristotle states that the sickness of the soul follows the sickness of the body, and the sickness of the body follows and accompanies that of the soul.... It is therefore useful for physicians not to forget to help the body, providing it with things that are humid and keep the organism in a lukewarm temperature. And avoid specifically drying food,…offer lukewarm sitting baths, and afterward rub them with violet's oil. And then they may eat food that is cold and humid and of easy digestion,…and a good young wine mixed with water.

In sum, al-Israeli espoused an integrative mind-body approach: supportive therapy, a therapeutic milieu that includes music, warm baths and massage, easily digestible food, and light alcoholic beverages. Overall, his therapeutic approach is, alas, much gentler—and probably more effective—than the sometimes violent approaches that were standard practice for many centuries after al-Israeli, both in Europe and in the United States, before the advent of talking therapies and, later, of the psychopharmacological revolution.