Decision making reflects a process of choosing among alternative options in order to achieve the outcome most beneficial to the decision maker (

1). Substance abusers often display impulsive decision making, with choices that yield high immediate gains but higher future losses. This decision-making deficit can be measured by tasks such as the Iowa Gambling Task or the Cambridge Gambling Task (

2–

6), which simulate real-life decision making in which an individual needs to weigh reward and punishment probabilities in light of uncertain outcomes. Impaired decision making may contribute to relapse by interfering with assessment of the consequences of drug use (

7). It is not known whether decision-making impairments improve as the length of abstinence increases. In the present study, we used the original card version of the Iowa Gambling Task to examine the time course of decision making in formerly heroin-dependent individuals who were abstinent for a period of 15 days to 2 years.

Another known risk factor for drug relapse is stress (i.e., the processes involving perception, appraisal, and response to harmful, threatening, or challenging events or stimuli) (

8–

12). Exposure to stress can promote relapse to drug use even after long periods of withdrawal (

13). Stress responses are partly mediated by the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which controls the secretion of hormones from the pituitary gland and adrenal cortex. Dysregulation of the HPA axis impairs the ability to respond adaptively to stress. Animal studies have shown that β-adrenergic antagonists block stress-induced reinstatement of opiate seeking and conditioned place preference (

14,

15).

In the present study, we tested whether stress would impair decision making in individuals recovering from heroin dependence after different durations of abstinence and whether this effect would be at least partly blocked by the β-adrenoceptor antagonist propranolol.

Method

The study was approved by the Peking University Research Ethics Board. The study's procedures and risks were discussed thoroughly with each participant, and all participants provided written informed consent and received monetary compensation for taking part in the study.

Participants

A total of 370 male formerly heroin-dependent inpatients who had been drug free for 3 days to 24 months were enrolled in the Compulsory Addiction Rehabilitation Center, Hubei province, China. The patients had used heroin in the community before being hospitalized in the rehabilitation center, and they had been treated with methadone for 7–10 days before entering the center's drug-free program, except those in the 3-day group, who received methadone treatment for 3 days. Healthy comparison subjects were recruited through advertisements followed by telephone screening. Of the 46 healthy comparison subjects initially screened, five did not participate in the study (two were excluded because they were receiving medication, and three were excluded because of medical diagnoses that precluded participation). Prior to enrollment, all participants were screened using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV and underwent a thorough interview about their medical history as well as a physical examination (ECG, blood pressure, heart rate measurements) and clinical laboratory tests (blood chemistry and urine testing). Patients had to provide answers to questions regarding their heroin abuse. All participants were aged between 20 and 40 years. Patients were required to meet DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for a history of opiate dependence and could not have any current medical illness requiring pharmacological treatment or any other substance use disorder, with the exception of nicotine dependence. Some of the other exclusion criteria were a history of head injury, a self-reported history of severe mental illness or psychosis, neurological disorders, or risk factors for side effects from propranolol administration (i.e., bradycardia, history of cardiogenic shock, history of hypotension, asthma, or abnormal ECG). Each participant was permitted to be in only one abstinence-time test. There were three group assignments. In experiment 1 (N=175), patients who had been drug free for 3 days (N=18), 7 days (N=19), 15 days (N=18), 30 days (N=20), 3 months (N=19), 6 months (N=19), 12 months (N=21), or 24 months (N=20) and healthy comparison subjects (N=21) underwent the Iowa Gambling Task to test the time-dependent effects of prior heroin dependence on decision making. In experiment 2 (N=118), patients who had been drug free for 15 days (N=18), 30 days (N=23), 3 months (N=20), 12 months (N=19), or 24 months (N=18) and healthy comparison subjects (N=20) underwent psychosocial stress to test the effects of stress on decision-making performance. In experiment 3 (N=118), patients who had been drug free for 30 days (N=41), 12 months (N=40), or 24 months (N=37) were randomly assigned to two subgroups (placebo or 40 mg propranolol 1 hour before psychosocial stress) to test the effect of propranolol on stress-induced exacerbation of decision-making impairments.

Questionnaires and Neuropsychological Measures

Barratt Impulsiveness Scale

Subjects were administered the Chinese version of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale, version 2, a validated 30-item questionnaire that measures different dimensions of impulsivity (

16) (see the data supplement accompanying the online version of this article).

Working memory (digit-span test)

Working memory was assessed using the digit-span test, which consists of the following two subtests: forward (simple attention) and backward (concentration, complex attention) (

17) (see the data supplement).

The d2 test of attention/psychomotor speed

From a series of the letters “d” and “p,” with one or two lines above and/or below each letter, the participants were asked to mark the ds containing two lines as quickly and accurately as possible (

18) (see the data supplement).

Iowa Gambling Task

We used the original card version of the Iowa Gambling Task to evaluate decision-making performance. The task was administered according to the procedure described in previous studies (

19,

20). In the task, participants are presented with four different decks of cards and asked to select one card at a time, with the goal of maximizing their “jackpot” over 100 card choices. Unbeknownst to the participant, two of the four decks are “advantageous.” Gains from these decks are relatively modest, but losses are modest as well, so that choosing these decks consistently will result in an overall gain in the jackpot. The other two decks are “disadvantageous.” Gains from these decks are high, but losses are even higher, so that choosing these decks consistently will result in an overall loss from the jackpot. The outcome measure for this task is the net score (total number of selections from the advantageous decks minus the total number of selections from the disadvantageous decks, ([C+D]–[A+B]). Healthy individuals gradually switch their preference toward the advantageous decks (C and D) and away from the disadvantageous decks (A and B).

Trier Social Stress Test

The Trier Social Stress Test is a well-established laboratory method for producing subjective stress accompanied by measurable cardiovascular and neuroendocrine responses (

21,

22). In the present study, the test was conducted by a group of staff (two to three examiners wearing formal coats in a laboratory room with a video camera and tape recorder). The test began with a 2-minute preparation period followed by 5 minutes of public speaking (a simulated job interview in which the participant had to introduce himself and describe his experience and personality). Immediately following the 5 minutes of speaking, the participant was asked to perform mental arithmetic (e.g., subtract 13 from 2,308) and read the results loudly and as fast and accurately as possible. On every mistake, the participant had to start over again from the first subtraction (

21,

23). The control condition consisted of a 5-minute casual conversation with a tester (about a movie or a book) and 5 minutes of rest.

Clinical Assessment

Heart rate and blood pressure

Systolic and diastolic blood pressure were measured with an arm cuff connected to a 9062D monitor (Baozhong Biotechnology Company, Beijing, China). Heart rate was measured continuously with a fingertip pulse sensor connected to an SD-700 monitor (

24).

Cortisol levels

Saliva was collected using Salivette collection devices (Sarstedt, Nümbrecht, Germany). The samples were stored at +4°C for 1–4 days and then frozen at –20°C. Free cortisol levels were detected by a radioimmunoassay kit (Immuno-Biological Laboratories, Furui Company, Beijing, China). The intra-assay and interassay coefficients of variation were less than 5% and 10%, respectively.

Procedures

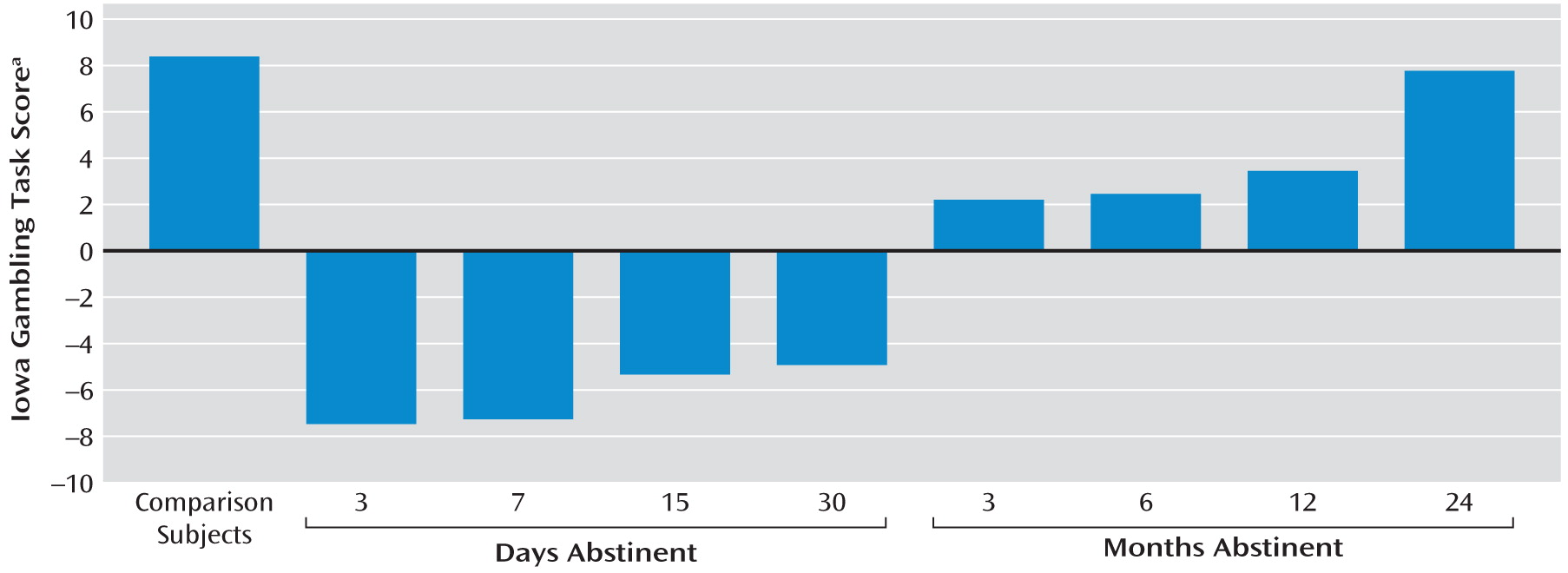

Experiment 1: time-dependent effects of abstinence on decision-making performance

After enrollment, each participant only attended one testing session at the clinical laboratory. Upon arrival, the experimental procedure was explained. Following a 15-minute adaptation time in which participants were asked to relax, each completed the questionnaires (Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale, Beck Depression Inventory, Barratt Impulsiveness Scale, version 11) and neuropsychological tests (working memory test and d2 test of attention) (see Table 1 in the data supplement accompanying the online version of this article). After another 15-minute rest, participants were tested with the Iowa Gambling Task.

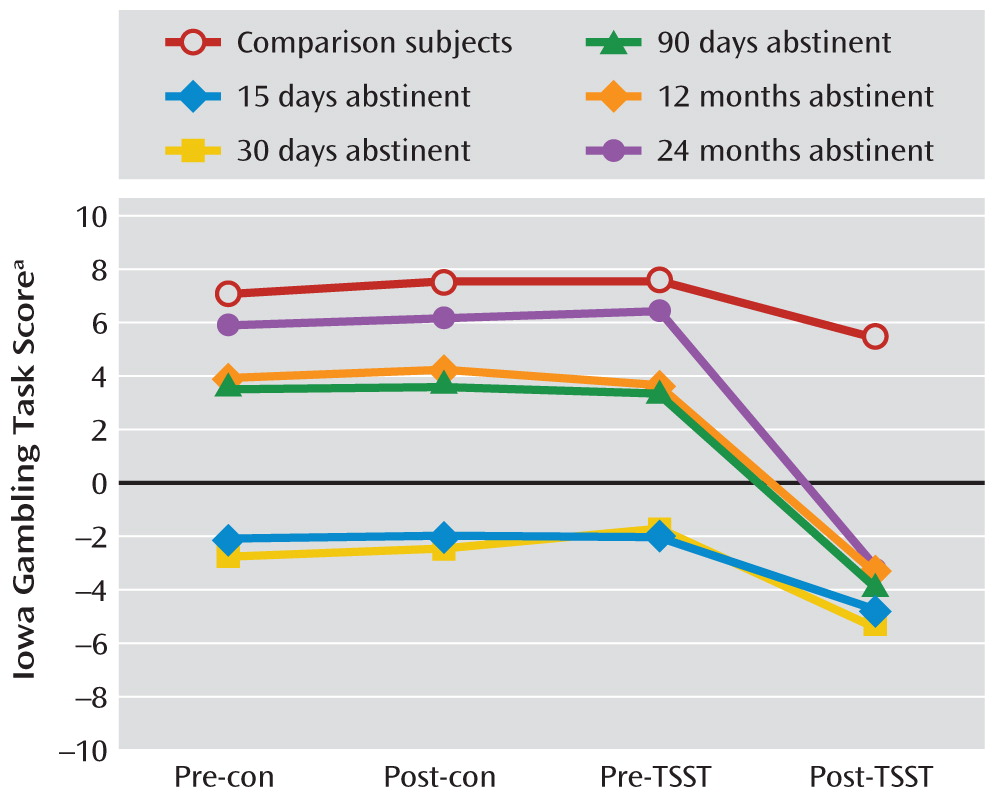

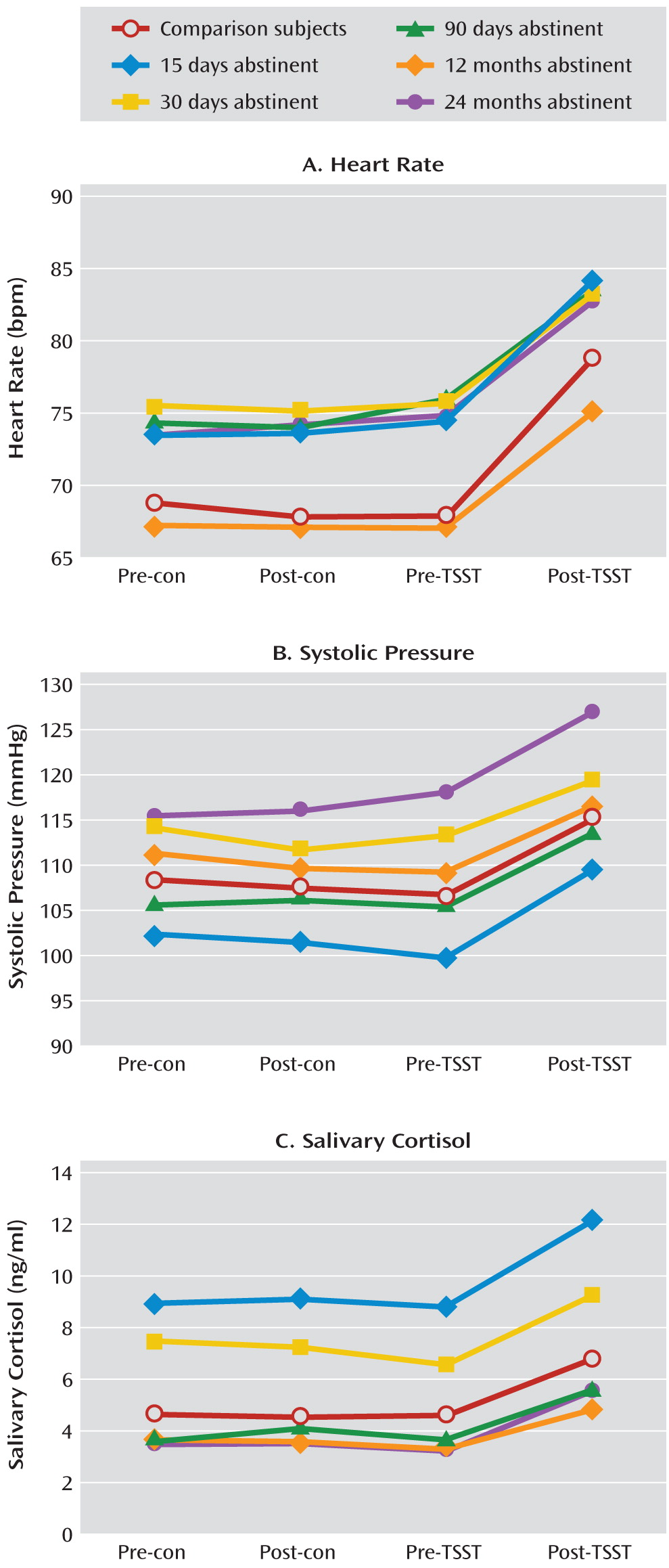

Experiment 2: effects of stress on decision-making deficits

As in experiment 1, each participant completed the questionnaires and neuropsychological tests. After a 15-minute rest, the participant was challenged with the Trier Social Stress Test and a control conversation in a counterbalanced sequence. The Iowa Gambling Task was administered at pre- and post-Trier Social Stress Test time points as well as pre- and post-control time points. Heart rate, blood pressure, and salivary cortisol levels were also measured at these time points. Participants were allowed to leave the laboratory when their systolic blood pressure and heart rate returned to baseline levels.

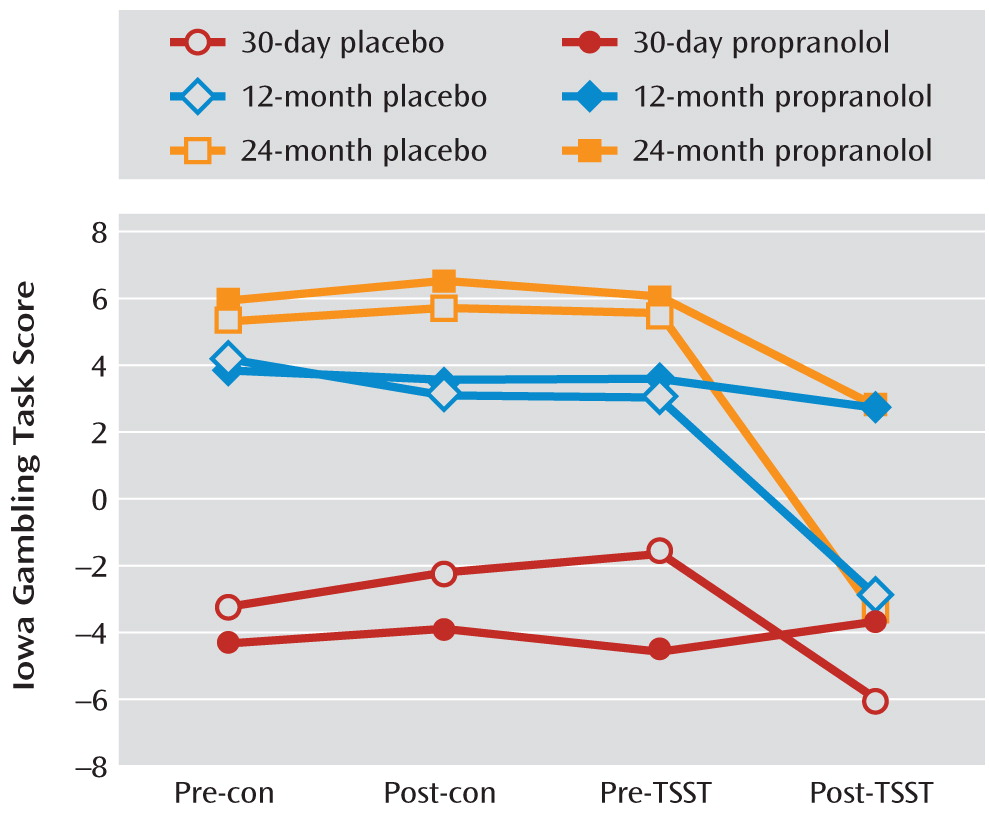

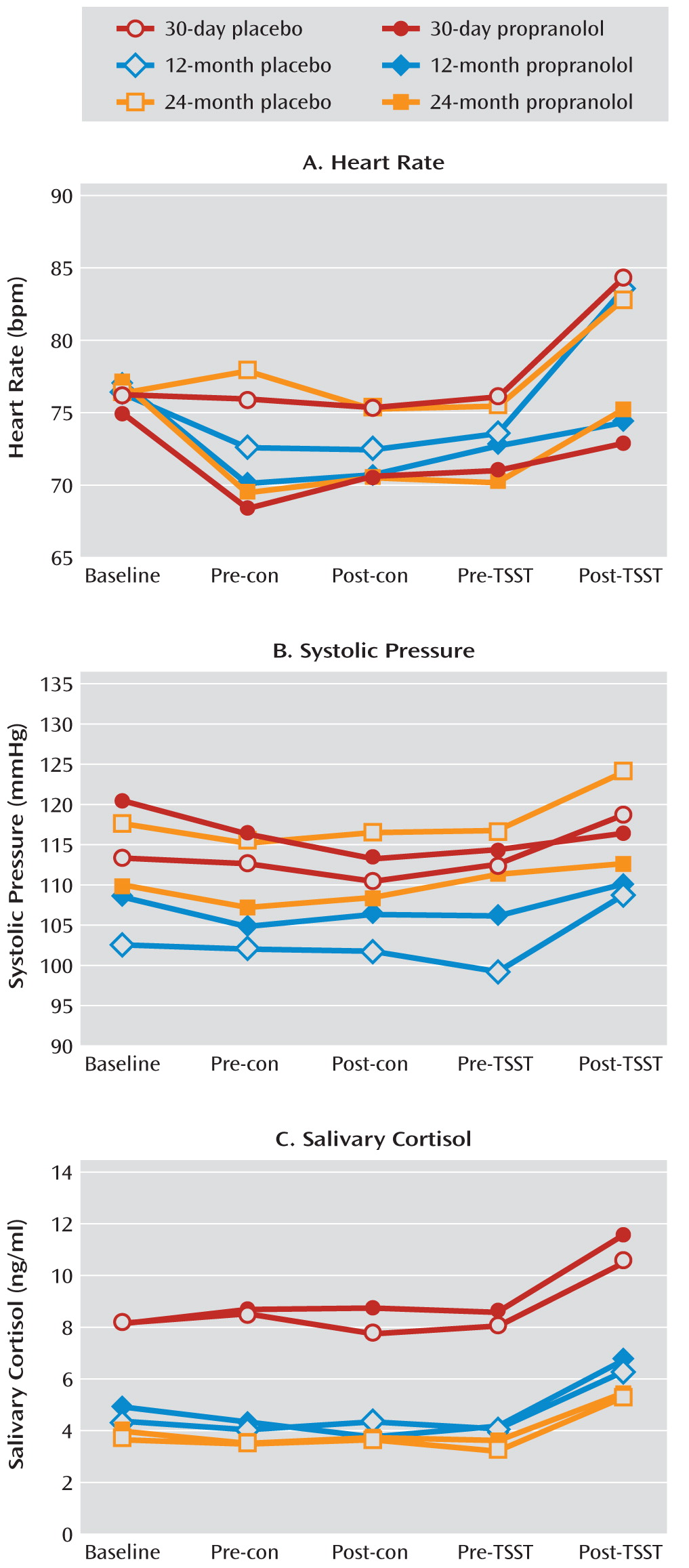

Experiment 3: effects of propranolol on stress-induced exacerbation of decision-making impairments

This was a double-blind, placebo-controlled drug-administration study. As in experiment 1, patients completed questionnaires and neuropsychological tests. After placebo or propranolol administration (orally, 1 hour before testing), the Trier Social Stress Test and a control task were given in counterbalanced sequence, using procedures and outcome measures identical to those in experiment 2.

Data Analysis

All data were analyzed with SPSS, version 13.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago). One-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were used for between-group comparisons of demographic characteristics (age, years of education, duration of heroin use, typical dose), neuropsychological task performance (working memory test and d2 test of attention), and psychiatric symptoms, including anxiety, depression, and impulsivity. For experiment 1, Iowa Gambling Task scores were analyzed by one-way ANOVAs with the factor group. For experiment 2, these scores and physiological measures were analyzed by repeated-measures ANOVAs with the between-subjects factors group (comparison group and 15-day, 30-day, 3-month, 12-month, and 24-month abstinence groups) and the within-subjects factors stress (Trier Social Stress Test, no Trier Social Stress Test) and time (pre, post). For experiment 3, Iowa Gambling Task scores and physiological measures were analyzed by repeated-measures ANOVAs with the between-subjects factors group (30-day, 12-month, and 24-month abstinence groups) and treatment (placebo or propranolol) and the within-subjects factors stress (Trier Social Stress Test, no Trier Social Stress Test) and time (pre, post). Post hoc tests were conducted with Fisher's least significant difference. The criterion for statistical significance was a p value ≤0.05 (two-tailed).

Discussion

This is the first study on the time course of decision making after heroin abstinence. A difference in decision-making deficits existed between the short-term abstinence groups (3, 7, 15, and 30 days), the longer-term abstinence groups (3, 6, and 12 months), and the longest-term abstinence group (24 months). In formerly heroin-dependent patients with durations of abstinence up to 24 months, decision-making performance tended to be similar to that of healthy comparison subjects. The group difference probably reflected a recovery of brain function with abstinence but may also suggest that poor decision making caused poor treatment outcome. These two possibilities are not mutually exclusive. Stress impaired decision making in all groups of patients, even in those who had been abstinent for 24 months, but not in healthy comparison subjects. The deleterious effect of stress on decision making was blocked by the β-adrenoceptor antagonist propranolol in the 30-day, 12-month, and 24-month abstinence groups. These findings suggested that in spite of the fact that decision making after 24 months of abstinence was not different from that seen in healthy comparison subjects, stress was able to disrupt decision making in more recently detoxified patients recovering from dependence, unmasking latent vulnerability, which required β-adrenergic stimulation.

All of the patients scored higher on the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale questionnaire, even in the absence of a stressor, and all except the 24-month abstinence group had poorer decision-making performance on the Iowa Gambling Task than comparison subjects. These results are consistent with previous studies on decision making using the Iowa Gambling Task (

6,

25) and partially consistent with previous investigations on decision making under ambiguity in patients with opiate dependence using other neuropsychological paradigms such as the Game of Dice Task (

26) and the Cambridge Gambling Task (

27,

28). A study on decision-making deficits in smokers revealed that a higher proportion of past 7-day smokers performed more poorly on the Iowa Gambling Task than nonsmokers and irregular smokers (ever or within the past 30 days) (

29). Moreover, a significantly higher proportion of past 7-day smokers were susceptible to future smoking. A similar study in binge drinkers showed distinctly different patterns of performance on the task between binge drinkers and “never-,” “ever-,” and “past-30-day” drinkers (

30). Better understanding of the impairment and recovery of decision making might improve treatment interventions for substance use disorders. In addition, the present study found no differences in digit span and d2 attention/psychomotor speed assessments among the groups. This suggested that decision-making impairment can be separated from general cognitive intelligence and attention impairment.

The greatest significance of the finding is the first demonstration of an exacerbating effect of psychosocial stress on decision-making deficits, even in long-term abstinent heroin users who are unimpaired on the task under normal circumstances. Stress-related drug use is typically explained in terms of negative reinforcement and in terms of stress-related increases in the incentive value of the drug (

31–

34). Stress is thought to play a major role in relapse (

9–

12). In laboratory studies with cocaine-dependent individuals, imagery-induced stress produces notable activation of the HPA axis and the sympatho-adreno-medullary pathway, accompanied by increases in cocaine craving (

35). The HPA response to stress may be a biological marker for future treatment dropout or relapse to cocaine abuse (

36,

37). Effects of stress on decision-making performance may help explain the psychobiological mechanisms underlying the association between stress and drug-seeking behavior in humans. The Iowa Gambling Task requires individuals to learn and infer from rewards and punishments encountered during the task (

38,

39) and specifically to choose long-term gains over more salient short-term gains. Impairment in that form of learning could underlie relapse to drug use during attempts at abstinence. The effect of stress on performance during this task was partly blocked by propranolol, but the stress-induced increase in cortisol level was not blocked by propranolol, which suggests that the effects of stress were mediated by a β-adrenergic mechanism rather than a glucocorticoid mechanism.

Some limitations of our study should be noted. First, repeated administration of the Iowa Gambling Task could lead to practice effects. However, no such effects were seen in patients with ventromedial prefrontal cortex lesions (

40), who in some respects are behaviorally similar to individuals with substance use disorders, for example, in choosing immediate rewards and ignoring future consequences (

41). Practice effects in our study were mitigated by the crossover design used in experiments 2 and 3. The second potential limitation was that we used a separate group to represent each abstinence time rather than an ideal within-subjects design with decision-making performance assessed longitudinally in one group of patients recovering from heroin dependence. Thus, we cannot rule out the possibility that the decision-making differences among groups reflected preexisting differences. The third limitation of our study was that the differential effects of stress seen in experiment 2 were evident only in exploratory post hoc t tests and were not reflected in omnibus interaction terms. These findings will require replication. Another limitation was that only men were enrolled in the study. Future investigation will need to examine possible sex differences.