Adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) are at elevated risk for deficient emotional self-regulation (DESR) (

1–

6). DESR refers to 1) deficits in self-regulating the physiological arousal caused by emotions, 2) difficulties inhibiting inappropriate behavior in response to either positive or negative emotions, 3) problems refocusing attention from strong emotions, and 4) disorganization of coordinated behavior in response to emotional activation (

4). DESR traits include low frustration tolerance, impatience, and quickness to anger as well as being easily excited in response to emotional reactions. Although Wender (

7) and subsequently others (

4,

8,

9) have identified these traits as common in presentations of ADHD in adulthood, in DSM-IV they are not considered diagnostic of the disorder.

Understanding the nature of DESR among ADHD patients is consequential because DESR can be confused with mood disorder symptoms that can be comorbid with ADHD. DESR is distinct from severe mood dysregulation, as described by Leibenluft et al. (

10), and also differs from the persistent and severe aggressive irritability often seen in pediatric bipolar disorder (

11). Unlike DESR, these latter conditions are not defined by poor self-regulation, and their definition includes features that are not part of DESR (e.g., the other mood symptoms of bipolar disorder and the hyperarousal of severe mood dysregulation).

The difference between DESR associated with ADHD and the mood instability of pediatric bipolar disorder is of particular importance given that these two disorders respond to different pharmacologic treatments. Notably, bipolar disorder is far less prevalent than DESR in ADHD patients, with approximately 15% of clinically referred ADHD adults having a lifetime history of bipolar disorder (

12). In contrast, Barkley et al. (

3) found that 60% of adults with ADHD in a clinical sample reported traits of DESR, relative to 15% of comparison subjects. Similar symptoms were seen in one-third of adults with ADHD participating in registration trials for atomoxetine (

13) and in more than one-half of adult patients in a smaller clinical trial of osmotic-release oral system methylphenidate (

2). Barkley and Fischer (

14) showed a higher prevalence of DESR in adults with ADHD with persistent symptoms relative to those without persistent symptoms. In their sample, DESR was correlated with functional impairment beyond that accounted for by ADHD. We recently found that 61% of a sample of community-ascertained adults with ADHD reported DESR of greater severity than 95% of comparison subjects (

6). DESR was only partially accounted for by other comorbid psychiatric conditions and was associated with significant adverse effect on quality of life.

Hypothesis 1 posits that ADHD and DESR are etiologically independent and co-occur as a result of chance. It predicts equally high rates of ADHD in relatives of ADHD probands and ADHD plus DESR probands (relative to comparison probands), but DESR should be increased only among relatives of adults with ADHD plus DESR (relative to comparison probands). Additionally, ADHD and DESR should not cosegregate in families of ADHD plus DESR probands (i.e., the ADHD relatives should not be at increased risk for DESR). Refuting this hypothesis would eliminate any hypothesis suggesting that the association between ADHD and DESR is a result of a referral bias (such as Berkson's bias) in which patients with multiple conditions are overrepresented in referrals because of the greater severity of their clinical picture. Given that there are no population studies of ADHD and DESR to discount such biases, testing this hypothesis is essential to rule out this potential artifact, which could explain the association of the two conditions.

Hypothesis 2 theorizes that ADHD with DESR is a distinct subtype or an entirely separate condition. It predicts the same pattern as hypothesis 1, with the exception that it predicts strong evidence for cosegregation among relatives of ADHD plus DESR adults (i.e., ADHD and DESR should be comorbid among relatives).

Hypothesis 4 speculates that ADHD adults with and without DESR share common familial etiologic factors but differ because of nonfamilial environmental effects. This hypothesis predicts similar rates of ADHD and DESR in the relatives of both subgroups.

Hypothesis 5 posits that DESR among adults with ADHD is a subsyndromal manifestation of another familial disorder such as depression or oppositional defiant disorder. If this is correct, then the relatives of ADHD plus DESR probands should be at higher risk for such disorders compared with the relatives of ADHD probands.

Results

Familial risk analyses were conducted for 43 siblings of 33 comparison probands, 40 siblings of 23 ADHD probands, and 45 siblings of 27 ADHD plus DESR probands. As seen in

Table 1, there were no significant differences in age and gender between the groups. There was also no significant difference in Hollingshead-Redlich socioeconomic status between the siblings of the three proband groups. We therefore did not need to control for differences in these variables in our familial risk analyses.

Familial Risk Analyses

Relative to comparison subjects, ADHD was more prevalent in the siblings of probands with ADHD, irrespective of the presence or absence of DESR. ADHD was present in 47.5% of the siblings of ADHD probands versus 7.0% of the siblings of comparison probands (χ2=17.5, df=1, p<0.001). ADHD was present in 60% of the siblings of ADHD plus DESR probands versus 7.0% of the siblings of comparison probands (χ2=27.5, df=1, p<0.001). The prevalence of ADHD in siblings did not differ significantly between ADHD probands with and without DESR (60% versus 48%, respectively).

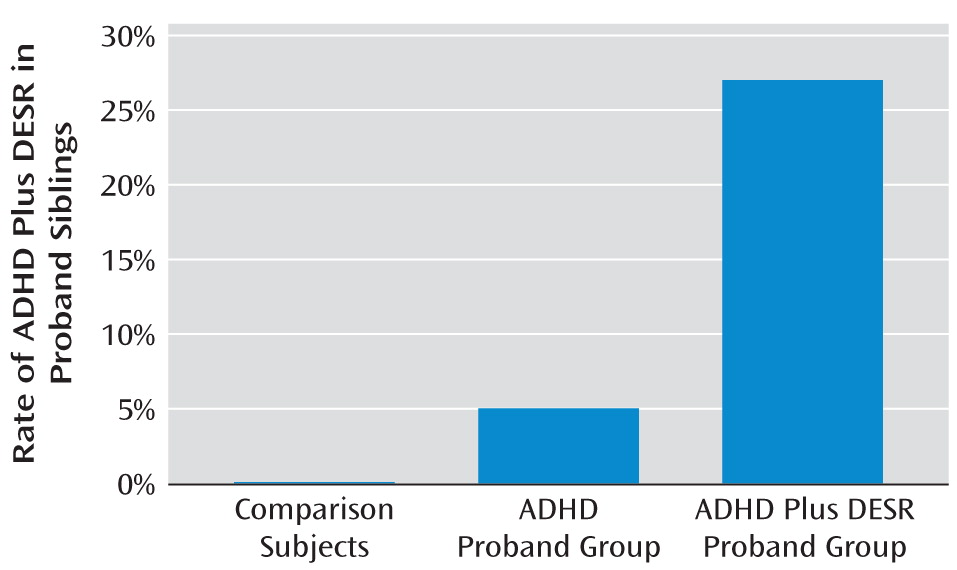

Siblings of ADHD plus DESR probands had significantly elevated rates of DESR relative to comparison probands (26.7% versus 0%, respectively; χ2=13.3, df=1, p<0.001), but the siblings of ADHD probands did not (5% versus 0%, respectively). DESR was also significantly more prevalent in the siblings of probands with ADHD plus DESR compared with the siblings of probands with ADHD (26.7% versus 5%, respectively; χ2=7.2, df=1, p<0.01).

We also found that ADHD and DESR cosegregated. The ADHD siblings of ADHD plus DESR probands were at elevated risk for DESR compared with non-ADHD siblings (44.4% versus 0%, respectively; χ2=10.9, df=1, p<0.01).

Nearly all cases of ADHD plus DESR in siblings occurred among siblings of ADHD plus DESR probands (χ

2=18.3, df=2, p<0.001 [

Figure 2]).

Table 2 shows the lifetime prevalence of psychiatric disorders in siblings of the three proband groups. Relative to siblings of comparison subjects, siblings of both ADHD plus DESR probands and ADHD probands had significantly higher rates of major depression, oppositional defiant disorder, and alcohol dependence. Siblings of ADHD plus DESR probands additionally had significantly higher rates of lifetime bipolar disorder, social phobia, and generalized anxiety disorder relative to the siblings of comparison probands. There were no significant differences in the rates of any of these psychiatric disorders when comparing the siblings of ADHD plus DESR probands with siblings of ADHD probands.

Conclusions

Our findings support our second hypothesis, which posits that ADHD with DESR represents a distinct familial subtype of ADHD or an entirely separate familial condition. Familial risk analysis revealed that ADHD was transmitted in families irrespective of the presence or absence of DESR, but DESR was only elevated among siblings of adult ADHD probands with DESR. We also found evidence for cosegregation between ADHD and DESR among siblings of ADHD plus DESR probands. This is seen most clearly in

Figure 2, which shows that nearly all cases of ADHD plus DESR among siblings were in families of ADHD plus DESR probands.

Although referral biases (such as Berkson's bias) could explain the comorbidity of ADHD and DESR among probands, such biases would not artifactually inflate the comorbidity of ADHD and DESR among relatives. Thus, our cosegregation findings eliminated hypothesis 1. Ideally, population studies of ADHD and DESR, which are lacking, would document this absence of referral bias. In the absence of such studies, our data are the strongest available to show that the high rate of DESR among ADHD probands is unlikely to be an artifact of referral.

The fact that DESR is restricted to families in which DESR and ADHD co-occur suggests that DESR is not simply a secondary manifestation of ADHD or another class of ADHD symptoms. If that were true, then rates of DESR should have been elevated among siblings of ADHD probands, since many of these siblings had ADHD. Because we did not see this elevation of DESR, it suggests that this deficiency does not routinely occur in ADHD patients but only in a subgroup. It is possible that DESR is secondary to ADHD but only in a familial context in which DESR occurs. For example, in some families, intrafamilial factors (e.g., modeling, social learning) may disrupt the normal developmental trajectory of increasing self-regulation with age. Such effects may be stronger in ADHD family members given that their disorder interferes with learning and compromises the self-regulation of cognitions and behavior. Such intrafamilial effects could explain the pattern of findings we observed. Because the prevalence of ADHD was similar between siblings of ADHD and ADHD plus DESR probands, we can rule out hypothesis 3 and conclude that ADHD plus DESR is not caused by having a loading of familial transmissible factors greater than ADHD. If a nonfamilial environmental risk factor accounted for DESR among ADHD probands (hypothesis 4), then we should have found similar rates of ADHD and DESR in the relatives of both subgroups, but we did not.

To identify DESR, we measured traits such as low frustration tolerance, impatience, quickness to anger, and being easily excited. These traits could present clinically in either the presence or absence of other mental health conditions such as mood disorders. If DESR among ADHD probands was an expression of another psychiatric disorder, we would have expected to find a higher prevalence of that psychiatric disorder among siblings of ADHD plus DESR probands compared with ADHD probands (hypothesis 5). In contrast to this prediction, we found no significant difference in the lifetime rate of any psychiatric disorders when comparing these two groups. This suggests that the DESR identified in probands with ADHD is not an expression of any of these familially transmissible disorders. We make this conclusion with caution because it derives from a failure to find significant differences, which could be a result of limited statistical power. However, the suggestion that DESR is not a manifestation of another psychiatric disorder is consistent with our demonstration that current and lifetime axis I conditions do not account for manifestation of DESR in the ADHD probands from the present study, as we previously demonstrated (

6).

Our findings have several implications for clinical and research investigation. From a clinical perspective, the assessment of DESR should help identify a relatively homogeneous group of ADHD patients. Prior studies have shown these patients to be at high risk for other psychopathology and severe functional impairments (

5,

6). Our study further emphasizes that, in addition to having distinct clinical features, this group of ADHD plus DESR patients may be distinct from other ADHD patients with regard to risk factors. This possibility further suggests that ADHD research would benefit from the stratification of ADHD patients into those with and without DESR, since the former may be a more homogeneous group with regard to treatment response (

24), neuroimaging parameters, or predisposing genetic variants (

25).

Improvements in the assessment and identification of DESR should help clinicians better differentiate DESR from other forms of comorbid mood disorders associated with ADHD. While many studies show that ADHD is associated with major depression and bipolar disorder, the cardinal feature of these disorders is the experience of strong emotions, not self-regulation (

26). These disorders are also associated with nonmood criteria, including somatic and behavioral impairments. For example, a patient in an episode of irritable mania expresses extreme and protracted irritability throughout the episode, not only in response to provoking stimuli. In contrast, ADHD patients with DESR do not have distinct episodes of DESR. Because they cannot self-regulate their emotional response, they respond to a provoking objective stimulus in an exaggerated manner, and thus the response becomes inappropriate in its magnitude and duration. Equally important to differential diagnosis between comorbid mood disorders and DESR is that the expressions of DESR subside relatively rapidly (i.e., “hot temper” or labile mood) and do not form a distinct protracted episode that would qualify for a mood disorder. Thus, ADHD adults with DESR enjoy normal moods much of the time but become easily frustrated or angry with unexpected emotional challenges.

DESR also differs from the mood dysregulation of severe mood dysregulation that is defined in children by 1) markedly increased reactivity in response to emotional negative stimuli (e.g., rages, aggression), 2) abnormal mood between rages in the form of sadness or anger, and 3) hyperarousal (defined by at least three of the following traits: insomnia, agitation, distractibility, racing thoughts or flight of ideas, pressured speech, or intrusiveness) (

10). Unlike DESR, severe mood dysregulation must be present at least half of the day on most days. Thus, severe mood dysregulation differs from DESR in the presence of abnormal mood between emotional overreactions and the presence of hyperarousal traits. Finally, although DESR may lead to emotional lability, the latter term broadly refers to emotions that change rapidly and are usually inappropriate. Labile emotions could be caused by poor self-regulation in response to provoking stimuli, but such stimuli are not required, as in the case of dementias.

DESR is therefore distinct from the type of mood dysregulation seen in depression, bipolar disorder, and severe mood dysregulation. We showed this empirically in a prior report of the present sample that found DESR symptoms to be strongly associated with ADHD, independent of both current and lifetime comorbidity with mood and anxiety disorders (

6). In the present report, we now show that the familial transmission of DESR is also independent of these other types of mood dysregulation.

Another consideration for research is that DESR could be conceptualized as a quantitative trait, which like neuropsychological functioning shows a continuum of dysfunction not only in ADHD but also for other disorders. Such an approach is consistent with the recently outlined Research Domain Criteria proposed by the National Institute of Mental Health (

http://www.nimh.nih.gov/research-funding/nimh-research-domain-criteria-rdoc.shtml). The Research Domain Criteria are dimensional measures ranging from normal to abnormal that cut across current diagnostic boundaries. Given that DESR is independently associated with ADHD and several other disorders, it could be used in this fashion. Future work would need to determine whether the ADHD plus DESR subtype we propose in the present study is simply one expression of DESR, which might also be seen, for example, as depression plus DESR in a family study of depression.

Our results should be interpreted with some limitations in mind. Through analysis of familial risk in the sibling relatives of probands, we have evaluated familial risk for DESR in adulthood and cannot make inferences about risk for DESR in other stages of development. Our sample did not allow exploration of the potential contribution of nonrandom mating to the pattern of inheritance of ADHD with DESR. We also were unable to disentangle the extent to which ADHD among adults with DESR might be secondary to DESR, which would require a sample of probands with DESR who did not have ADHD. It is also possible that our characterization of the familiality of DESR and its relationships with comorbidity were limited by power. It is further possible that intrafamilial factors (e.g., modeling, social learning) could explain familial manifestation of DESR. Thus, we cannot assert with complete confidence that we have accurately differentiated between all models for the coexistence of ADHD and DESR. Our sample was primarily of Caucasian ancestry and thus may not generalize to other ethnic groups.

Despite these limitations, we identified a pattern of familial risk consistent with the hypothesis that ADHD with DESR is a distinct familial subtype or variant of ADHD. Further work with other types of data (e.g., twins, extended relatives) is needed to provide stronger support for this hypothesis. Despite this limitation, we can firmly conclude that DESR is familial in ADHD families and that this familial transmission cannot be accounted for by other disorders. Replication of our findings, as well as further study of the genetic, neuropsychological, neurophysiological, and clinical correlates of ADHD with DESR, could clarify the importance of this putative ADHD phenotype.