Increasing evidence points toward a contribution of nongenetic factors to the etiology of psychotic disorders (

1,

2), and associations between childhood trauma and psychotic illnesses have been demonstrated (

3). However, given the use of retrospective reports of trauma, small samples, heterogeneous diagnostic groups, and lack of control for confounding variables (

4,

5), the role of childhood trauma in the etiology of psychosis remains controversial.

In this study, we capitalized on six research strategies to further our understanding of the relationship between childhood trauma and the development of psychotic disorders. First, we examined psychotic symptoms in childhood. Early psychotic symptoms represent a developmental risk for adult schizophrenia (

6) and thus provide a framework for investigating etiological factors for later psychosis. Second, we differentiated types of trauma based on the intention to harm. Different forms of trauma, such as neglect and sexual, physical, and emotional abuse, have been associated with psychosis (

5,

7), yet these findings offer little insight into the mechanisms underlying this association. Disentangling whether the intention to harm is the key element involved in trauma risk may suggest causal pathways from childhood trauma to later psychosis. Third, we used prospective measures of childhood trauma reported by mothers and psychotic symptoms reported by children themselves. Reliable prospective reports of childhood trauma that are not confounded by current symptoms are essential to ascertain unbiased associations between trauma and psychosis. Fourth, we disentangled the effects of trauma in early childhood and in midchild-hood. Trauma early in childhood may be specifically associated with psychotic symptoms because young children may not yet have developed coping strategies to deal with the consequences of experiencing trauma. Fifth, we tested the risk for psychotic symptoms associated with childhood trauma over and above individuals' genetic liability to developing psychosis. Psychotic symptoms in children who have been maltreated could be explained by genetic effects such as passive and evocative gene-environment correlations (

8). Passive gene-environment correlations may come about if parents who suffer from psychotic illnesses pass on to their offspring genes involved in psychosis and also expose their children to harmful experiences. Evocative gene-environment correlations may occur if children with a genetic liability to psychotic symptoms evoke harmful experiences from their environment. Sixth, we investigated whether childhood trauma moderates the effect of children's genetic vulnerability for developing psychotic symptoms early in life. Experiencing trauma in childhood could interact with children's genetic susceptibility to increase their risk of developing early signs of psychosis.

Using prospective measures of trauma (maltreatment, bullying, and accidents) collected repeatedly across 7 years, we examined the risk of developing psychotic symptoms in childhood associated with early life trauma in a nationally representative U.K. cohort of twins.

Results

Of the 2,232 twins in the study, 2,143 participated in the age-12 assessment; of these, complete data were available for 2,127 twins.

Table 1 presents the associations between childhood trauma across time and by presence or absence of psychotic symptoms at age 12. Three findings stand out. First, all types of trauma were associated with a higher risk for psychotic symptoms at age 12, but the effect was especially strong and consistent across time for trauma characterized by intention to harm. Second, self-reports of being bullied were more strongly associated with psychotic symptoms than were mother reports of bullying. The risk computed from self-reports of being bullied was nearly twice that computed from maternal reports. Third, the associations with psychotic symptoms were not consistent for accidents, which are characterized by unintentional harm. The associations were weaker compared with the two other types of trauma, and they were not consistent across time.

Psychotic symptoms at age 12 were significantly associated with socioeconomic deprivation, lower IQ, early symptoms of psychopathology (internalizing and externalizing problems), and genetic vulnerabilities (

Table 2). Childhood trauma with intentional harm was also associated with these confounding variables, whereas accidents were associated with externalizing problems only (

Table 3).

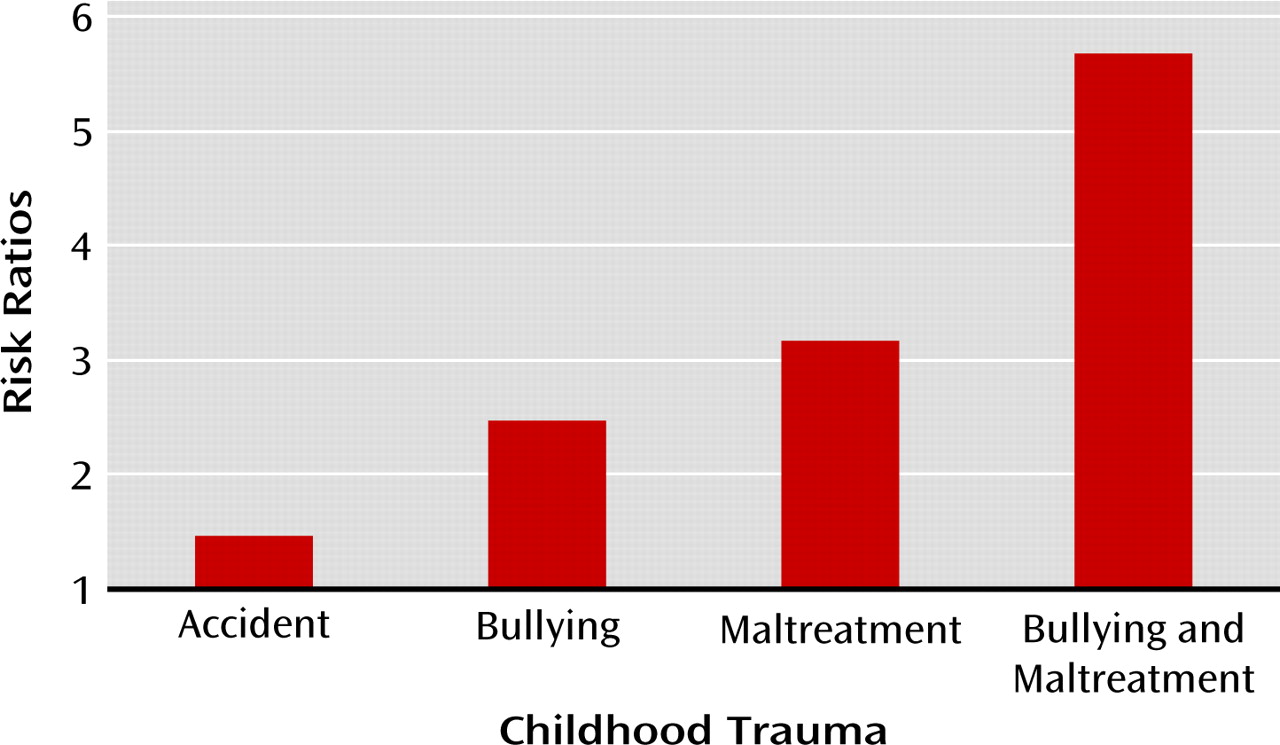

Table 4 presents the associations between lifetime childhood trauma and psychotic symptoms at age 12, controlling for confounding variables that could account for the associations observed. Three findings stand out. First, the associations between psychotic symptoms and lifetime trauma were not accounted for by children's gender, socioeconomic deprivation, IQ, early symptoms of psychopathology, or genetic vulnerabilities to developing psychotic symptoms. Second, the associations with accidents were weak and inconsistent across models controlling for confounders. Third, we found evidence for a dose-response relationship between a cumulative index of childhood trauma with intentional harm and children's psychotic symptoms. A total of 589 children (28%) had been either maltreated by an adult or bullied by peers by age 12, and 70 (3%) experienced both types of trauma. Compared with children who did not experience any trauma with intentional harm by age 12, those who experienced either maltreatment or bullying were 3.27 times (95% CI=2.25−4.76) as likely to report psychotic symptoms, and those who experienced both were 5.68 times (95% CI=3.18−10.14) as likely to report psychotic symptoms (

Figure 1). These elevated risks remained significant after controlling for confounding variables. Analyses further indicated that children's genetic vulnerability for developing psychotic symptoms was not moderated by the cumulative history of childhood trauma whether genetic risk was indexed by a maternal history of psychosis (z=−1.36, p=0.174) or the co-twin's symptoms (z=−0.55, p=0.582).

Discussion

Youths who report psychotic symptoms in their teens are at increased risk for developing psychotic illness later in life (

6). In our sample of 12-year-olds, we found that a history of childhood trauma increased the likelihood that children would report such symptoms. Maltreatment by an adult and bullying by peers were strongly associated with children's reports of psychotic symptoms. These findings concur with previous research but go a step further by showing that this effect is 1) consistent across early and late childhood trauma; 2) similar for maltreatment by adults and bullying by peers, which both involve intention to harm; and 3) independent of the confounding effect of socioeconomic deprivation, low IQ, early psychopathology, and genetic susceptibility to developing psychotic illnesses. Children who experience abuse early in life show adjustment problems such as posttraumatic disorders, depression, and conduct problems (

26). Our study, along with other reports, indicates that psychotic symptoms can be added to this list of harmful outcomes.

Our findings show consistency across types of trauma and across timing of the events. First, children's risks of reporting psychotic symptoms were similar across trauma characterized by intention to harm, whether these acts were perpetrated by adults or by peers. This finding suggests that an element of threat, or a perception of threat, could trigger psychotic symptoms, rather than the form the abuse may take (e.g., physical, sexual, or relational). However, our findings do not indicate that we can completely ignore the risk carried by forms of trauma that do not involve such intention. Children who experienced accidents at some point in their lives had a significantly higher risk of reporting psychotic symptoms (albeit before adjustment for confounding variables). Second, trauma was related to risk of psychotic symptoms in a dose-response fashion using a cumulative index of trauma, which is consistent with findings from another cohort of 12-year-olds (

11). The cumulative effect of abuse from adults and peers, rather than its timing, appears to confer the highest risk for developing psychotic symptoms.

There is growing evidence supporting the risks associated with being bullied during childhood (

27). Prospective data on trauma from population-based cohorts and samples of vulnerable youths converge in showing an elevated risk for psychosis among bullied children (

11,

28,

29). Our results show a consistent pattern across informants, indicating that results did not differ depending on who reported on children's bullying experiences, although the effects were larger for self-reports. It is conceivable that the use of self-reports of bullying and symptoms of psychosis may overestimate the risk for psychosis. First, the association may be inflated by having the same informant reporting on both bullying experiences and psychotic symptoms. Second, traumatic experiences and perception of threats may be part of the symptomatology of psychotic disorders. When children are asked about their experience of bullying, their report may be biased by their symptoms of psychosis. Alternatively, mothers and teachers may underreport instances of bullying because they are not fully aware of the children's experiences.

Research is needed to identify mechanisms that could explain psychotic symptoms among children who have experienced trauma. Neurodevelopmental changes associated with the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis could be one area of investigation (

30). Alterations of the HPA axis are known to be associated with early experience of trauma (

31,

32) as well as with psychotic illnesses (

33). Childhood psychotic symptoms could be a result of neuro-developmental changes in the HPA axis following repeated traumatic experiences. Cognitive distortion could also explain psychotic symptoms among people who experience trauma early in life (

34). A childhood marked by a history of victimization could have an impact on threat perceptions and generate symptoms of psychosis—more specifically, symptoms of delusions and hallucinations.

Our study has limitations. First, we studied a cohort of twins, and our results may not be generalizable to singletons. However, previous studies have found no differences between twins and singletons in the prevalence rates of maltreatment and bullying (

35,

36) or behavior problems (

37–39). Second, we assessed a set of only seven psychotic symptoms. However, our questions are well established, have been validated, and have been used in other studies (

6,

12,

40). Third, we remain uncertain about the timing of the psychotic symptoms, as they were not inquired about until age 12.

Early detection and targeted intervention for emerging psychotic symptoms have the potential to change the course of early psychopathology (

41). Our study has implications for clinicians working with children who report symptoms of psychosis. Assessment of trauma should be part of clinical interviews to ensure that maltreatment or bullying is not ongoing. Furthermore, intervention strategies should consider the possibility that young children who show early symptoms of psychosis may be growing up in threatening environments. Further studies are needed to strengthen the hypothesis that early trauma leads to symptoms of psychopathology in childhood, and not the reverse. In addition, neurobiological research should follow the lead from epidemiological studies and investigate the pathophysiological mechanisms linking trauma to psychosis. This would help guide early prevention efforts to reduce risk for psychotic symptoms among vulnerable children by, for instance, advising about the risks of early substance use (

42). Much remains to be learned about the etiology of psychosis and the development of preventive measures by broadening the scope of research to include the nonclinical phenotype (

43).