Major depressive disorder is highly prevalent (

1), comorbid with other mental disorders (

2), and a leading source of disease burden worldwide (

3). Prospective, longitudinal studies of patient samples show that major depressive disorder is a chronic illness, characterized by complex patterns of persistence, remission, and recurrence (

4,

5). Similarly, the treatment literature characterizes the disorder as a refractory illness, presenting challenges for both clinicians and researchers (

6).

Chronicity may be represented by prolonged time to recovery from an index episode (i.e., persistence) or by the occurrence of a new episode in a remitted case (i.e., relapse or recurrence). Identifying consistent predictors of the course of major depressive disorder (i.e., of remission, relapse, or persistence) has been difficult (

4,

5). Recurrence and the number of prior episodes are associated with delayed remissions and accelerated relapses (

7,

8). Patients with major depressive disorder and co-occurring dysthymic disorder (i.e., double depression) have more chronic courses than those without this comorbidity (

9,

10). Other axis I disorder comorbidity (

11), early onset (

12), and female gender (

13) have also been shown to be predictors of chronicity, although not in all studies (

5).

Personality disorders have received increasing attention as prognostic factors for the course and outcome of major depressive disorder. Critical reviews of naturalistic (

14) and treatment (

15) studies suggest that personality disorders have a negative effect on course. However, this literature is also mixed, and disparate findings likely reflect methodological limitations, including cross-sectional and retrospective rather than longitudinal and prospective designs, short-term follow-up intervals, assessment of few personality disorders, lack of standardized diagnostic interviews, and sample sizes insufficient to allow for multivariate analyses controlling for potentially confounding variables.

The Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study (

16) was designed to provide comprehensive data on the course and outcome of patients with personality disorders, many of whom had major depressive disorder, and a comparison group of patients with major depressive disorder but no personality disorder. In the initial 2-year analyses, personality disorders predicted slower remission from major depressive disorder, even when controlling for other negative prognostic predictors (e.g., gender, ethnicity, axis I comorbidity, dysthymic disorder, recurrence, age of onset, treatment) (

17). More recent 6-year follow-up analyses extended these remission results and found that among those whose major depressive disorder remitted, patients with borderline and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders had shorter time to relapse than patients without personality disorders (

18).

Although prospective studies of patient samples, such as the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study, provide important information, patient studies may be biased by numerous confounds and selection factors (

19). To better understand the course of major depressive disorder and its predictors, prospective epidemiological studies are needed. To our knowledge, no such study has been conducted. The purpose of the present study, therefore, was to examine the effects of specific personality disorder comorbidity on the course of major depressive disorder in a nationally representative sample. The National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcoholism and Related Conditions is a two-wave, face-to-face survey of more than 43,000 adults in the United States (

20,

21). The 3-year follow-up interview of the survey's large sample provides the opportunity to determine the rates of persistence and recurrence of major depressive disorder in the community and the specific effects of all DSM-IV personality disorders on its course, while allowing for multivariate analyses to account for other potential predictors of chronicity. These data also present a unique opportunity to confirm the hypothesis generated in clinical populations (

17,

18) that personality disorders exert a strong, independent, negative effect on the course of major depressive disorder.

Method

Participants

Participants were 1,996 respondents in waves 1 and 2 of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (

20,

21). The target population consisted of civilian, noninstitutionalized individuals aged ≥18 years residing in households and group quarters (e.g., college quarters, group homes, boarding houses, nontransient hotels). African Americans, Hispanics, and individuals ages 18–24 years were oversampled, with data adjusted for oversampling and household- and person-level nonresponse. Of the 43,093 respondents interviewed in wave 1, respondents who were census-defined as being eligible for wave 2 reinterviews included those not deceased (N=1,403), deported, mentally or physically impaired (N=781), and on active military duty (N=950). In wave 2, a total of 34,653 of 39,959 eligible respondents were reinterviewed, with a response rate of 86.7%. Sample weights were developed to additionally adjust for wave 2 nonresponse (

21). In wave 1, a total of 2,422 respondents met criteria for current DSM-IV major depressive disorder. Of these, 1,996 participated in wave 2 and constitute the sample in the present study. In comparing the 1,996 respondents who were reinterviewed with the 426 not reinterviewed on predictors and covariates described in this article, lower follow-up likelihood was predicted by race/ethnicity (African American: t=−3.08, df=5, p=0.003; Asian: t=−3.00, df=5, p=0.004; Hispanic: t=−2.60, df=5, p=0.01), less than college level education (t=−3.24, df=2, p=0.002), unmarried status (t=−3.21, df=2, p=0.002), and dysthymic disorder (t=−2.60, df=2, p=0.01) but not by age; gender; any substance use disorder; any anxiety disorder; any axis II disorder; family history of major depressive, alcohol use, drug use, or antisocial personality disorders; age at onset; or current treatment for depression. Among the sample of 1,996 respondents, 67.5% were women, 74.1% were Caucasian, 9.1% were African American, 10.0% were Hispanic, 3.8% were Native American, and 3.1% were Asian. Approximately one-quarter (26.9%) were >30 years old during wave 1, and 20.1% were between the ages of 30–39 years, 24.7% were 40–49 years, and 27.9% were ≥50 years. A total of 49.9% were married or cohabitating, and 56.6% had at least a high school education.

Procedures

In-person interviews were conducted by experienced lay interviewers with extensive training and supervision (

20,

21). All procedures, including informed consent, received full ethical review and approval from the U.S. Census Bureau and U.S. Office of Management and Budget.

Assessment

Interviewers administered the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-DSM-IV version (

22), a structured diagnostic interview developed to assess substance use and other mental disorders in large-scale surveys. Computer algorithms produced diagnoses of DSM-IV axis I disorders and all DSM-IV personality disorders.

Major depressive disorder.

Major depressive disorder was defined as having at least one major depressive episode over the life course without a history of manic, mixed, or hypomanic episodes. Diagnoses additionally required meeting clinical significance criteria (i.e., distress or impairment), having a primary mood disorder (excluding substance-induced or general medical conditions), and ruling out bereavement (

1).

In wave 1, criteria for a major depressive episode were assessed for the following two time frames: 1) current (i.e., during the last 12 months) and 2) prior to the last 12 months. In wave 2, 3 years later, these criteria were assessed again for two time frames, covering the entire time period between waves 1 and 2, as follows: 1) current (last 12 months) and 2) prior to the last 12 months but since wave 1. From these data, the following two outcome variables were created: persistent major depressive disorder and recurrent major depressive disorder. Persistent major depressive disorder was defined as meeting full criteria for current major depressive disorder in wave 1 and full criteria for the disorder throughout the entire 3-year follow-up period, without the occurrence of mania. Recurrent major depressive disorder was defined as meeting full criteria in wave 1 and again during the last 12 months in wave 2 but not during the first 24 months after the wave 1 interview.

The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule has good test-retest reliability for major depressive disorder (kappa=0.65−0.73) in clinical and general population samples (

23,

24). Importantly, clinical reappraisals have shown that diagnoses determined by the DSM-IV version of the interview are consistent with diagnoses determined by psychiatrists (kappa=0.64–0.68; sensitivity=0.76; specificity=0.93) (

24).

Predictors of Outcomes

Predictor variables tested were 1) demographic characteristics, 2) other DSM-IV axis I disorders, 3) personality disorders, 4) clinical characteristics of major depressive disorder course, 5) family history, and 6) treatment history.

Demographic characteristics.

Demographic variables were gender, race/ethnicity, age, marital status, and education level.

Other axis I disorders.

The Alcohol Use Disorder and Asso-ciated Disabilities Interview Schedule-DSM-IV version operationalizes DSM-IV disorders for alcohol consumption, 10 drug classes, and nicotine use (

25,

26), with good to excellent interrater and test-retest reliability (e.g., kappa=0.70–0.84) and validity (

24). Dysthymic disorder and anxiety disorders, including panic, social anxiety, specific phobia, and generalized anxiety disorders, were assessed. Test-retest reliability was adequate for dysthymic disorder and anxiety disorders (kappa=0.40–0.69) (

24), and validity was indicated by significant associations with impairment on the 12-item Short Form Health Survey, version 2 (

27).

Personality disorders.

All 10 DSM-IV personality disorders were assessed by algorithms requiring the specified numbers of diagnostic criteria as well as evidence of long-term maladaptive patterns of cognition, emotion, and functioning (

28–32). Personality disorders, except antisocial personality disorder, were assessed with an introduction and repeated reminders asking respondents to answer how they felt or acted as follows: “most of the time, throughout your life, regardless of the situation or whom you were with.” Respondents were instructed not to include symptoms occurring only when depressed, manic, anxious, drinking heavily, using drugs, recovering from the effects of alcohol or drugs, or physically ill. Personality disorder criteria items were adapted from items in DSM-IV versions of semistructured diagnostic interviews (e.g., Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders, Personality Disorder Examination) that have long-standing histories of reliable use in research studies of patient groups (

33). For all symptoms coded positive, respondents were asked, “Did this ever trouble you or cause problems at work or school, or with your family or other people?” Scoring algorithms for diagnoses required endorsement of associated distress or social/occupational dysfunction, in addition to the number of specified criteria (

32).

Avoidant, dependent, histrionic, obsessive-compulsive, paranoid, and schizoid personality disorders were assessed in wave 1, and borderline, narcissistic, and schizotypal disorders were assessed in wave 2. Lifetime antisocial personality disorder was assessed in wave 1, with adult symptoms reassessed in wave 2. Antisocial personality disorder was considered present if the respondent met criteria for lifetime disorder in wave 1 and had at least three adult criteria that persisted in wave 2. Test-retest studies of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions indicate reliability ranging from fair (paranoid, histrionic, avoidant; kappa=0.40–0.45) to very good (schizotypal, antisocial, narcissistic, borderline; kappa=0.67–0.71) (

23,

34), which is generally comparable to the range reported for patient studies (

33,

35). Associations with impairment indicate good convergent validity for these diagnoses (

26,

28–32).

Because not all of the 10 personality disorders were measured in wave 1, we investigated their validity in both waves, among the 1,996 respondents, using two methods. The first method, using weighted linear regressions, compared respondents with a personality disorder with those without a personality disorder on impairment in waves 1 and 2, measured using the mental component summary of the Short Form Health Survey, version 2 (

27). Some between-wave change in scores occurred, as expected (

36), but participants with personality disorders consistently had greater (p<0.0001) impairment in both waves 1 and 2, regardless of the wave in which the disorder was as-sessed (for further details, see Table 1 in the data supplement accompanying the online version of this article). The second method, using logistic regression, compared respondents with a personality disorder with those without a personality disorder on life events in waves 1 and 2 that suggested impaired functioning, such as breaking up of relationships; problems with friends, employers, or finances; being fired or laid off; and being unemployed and looking for work. As summarized in Table 2 in the data supplement, respondents with personality disorders were more likely to experience these events in both waves, regardless of when their disorder was diagnosed. The consistency of association of both impairment indicators with personality disorders in waves 1 and 2, regardless of when the disorder was assessed, further supported the validity of the diagnoses.

Clinical characteristics of major depressive disorder course.

Since early onset, recurrence, and previous chronicity predicted persistent major depressive disorder in some studies (

7,

8,

12,

13), our analyses included age at first onset (>15 years, 15–17 years, ≥18 years) and the number of prior episodes and duration of the current episode.

Family history.

Family history of depression, antisocial personality disorder, and alcohol or drug use disorders were also investigated as predictors. Family history was assessed by reading observable manifestations of each disorder to the respondents and asking about disorders among their relatives, including parents and siblings. Test-retest reliability was good to excellent (

25).

Treatment history.

Treatment for major depressive disorder was examined, including outpatient services (counselor, therapist, physician, or other professional), inpatient services (hospitalized overnight or longer), and prescribed medication (

37).

Statistical Analyses

Weighted means, frequencies, and univariate associations were computed. Relationships between predictors and the two binary out-come variables (persistent and recurrent major depressive disorder) were tested with multiple logistic regression models, producing adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Standard errors (SEs) and 95% CIs for the predictors were estimated with SUDAAN (Research Triangle Institute International, Research Triangle Park, N.C.), which uses Taylor series linearization to adjust for design effects of complex sample surveys.

We first tested the individual effects of axis I disorders, adjusting for demographic characteristics. We then tested a model including demographic variables and all other axis I disorders, controlling for comorbidity to indicate any potential unique effect of each disorder. Bipolar I and II disorders were excluded from analyses.

We calculated population attributable risk proportions for an additive measure of the effect of the study predictors on major depressive disorder persistence. This fraction is calculated by subtracting the proportion of persistence in those with the predictor from the proportion of persistence among those without the predictor and dividing the difference by the proportion of persistence among those with the predictor. The resulting attributable risk indicates the proportion of the outcome that would not occur in the absence of the predictor.

To examine the effect of personality disorders on major depressive disorder persistence, we first tested individual models for each per-sonality disorder, controlling for demographic variables. We then added axis I disorders to these models to determine whether apparent personality disorder effects arose from axis I comorbidity. Next, we tested a model that included demographic variables, axis I disorders, and all 10 personality disorders simultaneously. Given the considerable comorbidity of personality disorders with each other (

38), this model was intended to control for the effects of all other personality disorders when examining each one to determine whether any specific one had unique effects. We then tested a model to indicate the robustness of unique personality disorder effects by adding family history. Finally, to further test the robustness of personality disorders as predictors, we tested a model with all of the demographic variables and axis I and personality disorders as well as family history plus age at onset of major depressive disorder, number of lifetime episodes, most recent episode duration, and current treatment for major depressive disorder.

Results

Of the 1,996 respondents diagnosed with major depressive disorder in wave 1, a total of 302 (15.1% [SE=1.0]) had persistent major depressive disorder in wave 2, meeting full criteria for the disorder throughout the entire 3-year follow-up period, without mania or hypomania. A total of 145 (7.3% [SE=0.7]) of the 1,996 respondents who had major depressive disorder in wave 1 and remitted went on to experience a subsequent recurrence.

Of the demographic variables, only gender predicted major depressive disorder persistence or recurrence. Male respondents were less likely than female respondents to have an episode persist (odds ratio=0.66, 95% CI=0.45–0.97) or recur (odds ratio=0.55, 95% CI=0.33–0.91) by wave 2. Among axis I disorders, dysthymic disorder (odds ratio=1.79, 95% CI=1.23–2.60), any anxiety disorder (odds ratio=1.96, 95% CI=1.43–2.68), specific phobia (odds ratio=2.19, 95% CI=1.53–3.12), and panic disorder (odds ratio=2.18, 95% CI=1.30–3.68) all predicted persistence. After additionally controlling for other axis I disorders, dysthymic disorder (odds ratio=1.75, 95% CI=1.20–2.54), specific phobia (odds ratio=2.08, 95% CI=1.46–2.99), and panic disorder (odds ratio=1.87, 95% CI=1.11–3.15) remained significant predictors of persistence. No comorbid axis I disorder predicted recurrence.

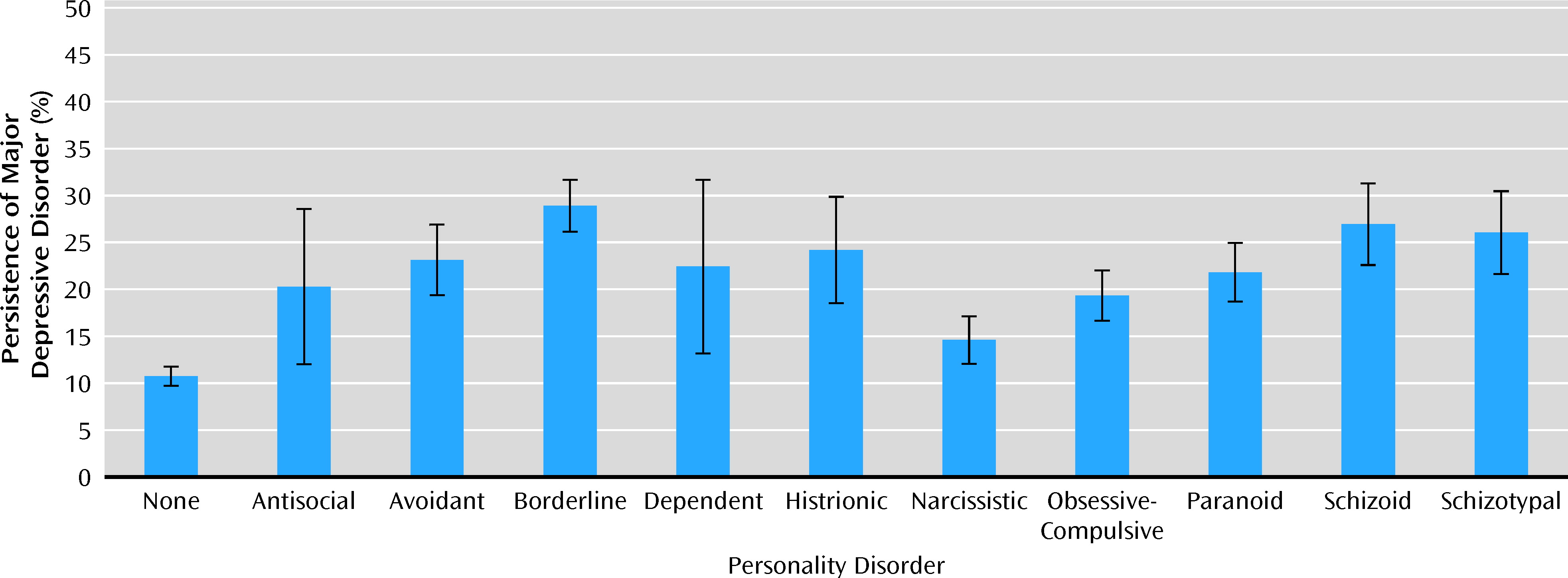

Figure 1 shows the percent of participants who had persistent major depressive disorder by status of each of the 10 personality disorders and no personality disorder. Among participants with a personality disorder, those with borderline personality disorder had the highest percent of persistence (28.9% [SE=2.75]), and those with narcissistic personality disorder had the lowest percent (14.6% [SE=2.52]). Several personality disorders predicted major depressive disorder persistence in univariate analyses, including avoidant (odds ratio=1.97, 95% CI=1.25–3.10), borderline (odds ratio=3.23, 95% CI=2.34–4.49), histrionic (odds ratio=2.20, 95% CI=1.14–4.24), paranoid (odds ratio=1.80, 95% CI=1.21–2.68), schizoid (odds ratio=2.46, 95% CI=1.54–3.95), and schizotypal (odds ratio=2.23, 95% CI=1.37–3.65) personality disorders. No personality disorder predicted recurrence.

No family history variable predicted persistence, but a family history of depression predicted recurrence (odds ratio=1.72, 95% CI=1.11–2.67). History of treatment for major depressive disorder predicted persistence (odds ratio=2.07, 95% CI=1.48–2.89) but not recurrence. Among other clinical features of major depressive disorder, earlier age at onset (odds ratio=0.97, 95% CI=0.96–0.99) and the number of previous episodes (odds ratio=1.02, 95% CI=1.01–1.03) weakly predicted persistence, while duration of the most recent episode did not. No clinical feature significantly predicted recurrence.

Table 1 presents the population attributable risk proportions for the effects of co-occurring psychopathology and related risk factors on the persistence of major depressive disorder. Those disorders with the highest values were borderline (57.3%), schizoid (47.9%), and schizotypal (45.3%) personality disorders as well as any anxiety disorder (43.4%).

Table 2 displays the results of the multivariate analyses testing the associations of personality disorders with major depressive disorder persistence. In model 1, which controlled for demographic factors, avoidant, borderline, histrionic, paranoid, schizoid, and schizotypal personality disorders all remained significant predictors. In model 2, with additional controls for axis I disorder comorbidity, avoidant, borderline, paranoid, schizoid, and schizotypal personality disorders again remained significant. In model 3, with all personality disorders added simultaneously to the model, only borderline and schizoid personality disorders remained significant. The addition of family history of psychiatric and substance use disorders (model 4) resulted in virtually no change in the results. When treatment history, age at first onset, the number of previous episodes, and duration of the current episode in wave 1 were added (model 5), borderline personality disorder re-mained a robust predictor of major depressive disorder persistence (odds ratio=2.51, 95% CI=1.67–3.77).

Discussion

This study provides a rigorous test of the effect of personality disorders on the course of major depressive disorder in a nationally representative sample assessed with a well-established instrument. A large number of participants were ascertained independently of treatment status and re-evaluated 3 years later, with excellent retention to determine the rates of persistence and recurrence of major depressive disorder. Our study tested the prognostic significance of personality disorders while controlling for demographic factors, psychiatric and other personality disorder comorbidity, clinical factors that could have affected the course of major depressive disorder, family history, and treatment history. The large sample allowed for multivariate tests of predictors in a logical progression that enabled the untangling of the effects of these multiple factors in a manner not possible in previous smaller studies.

In the present study, comorbid personality disorders, anxiety disorders, and dysthymic disorder significantly predicted persistence of major depressive disorder. According to population attributable risk proportions, borderline personality disorder was the strongest predictor, followed by schizoid and schizotypal personality disorders, any anxiety disorder (the strongest axis I disorder predictor), and dysthymic disorder. Population attributable risk proportions indicate the proportion of persistence of major depressive disorder attributable to each disorder. Thus, approximately 57% of cases would not have persisted into the follow-up period in the absence of borderline personality disorder, a larger proportion than any axis I disorder. Even after controlling for other potentially negative prognostic indicators, borderline personality disorder significantly and robustly predicted major depressive disorder persistence.

Overall, the 84.9% remission rate of major depressive disorder in this 3-year follow-up study is comparable to rates observed in two major National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH)-funded prospective studies of patient groups. The NIMH-Collaborative Depression Study reported major depressive disorder remission rates of 70% at a 2-year follow-up evaluation and 88% at 5 years (

14), while the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study reported remission rates of 73.5% at 2 years (

24) and 86% at 6 years (

25). Our findings that personality disorders are negative prognostic indicators for the course of major depressive disorder and that borderline personality disorder, in particular, is a robust independent predictor of chronicity are consistent with the findings from the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study (

17,

18) and from an earlier Norwegian study using DSM-III criteria (

39). Grilo and colleagues (

17) reported that the co-occurrence of personality disorders in patients with major depressive disorder predicted significantly longer time to remission, even when controlling for several other negative prognostic factors. Our findings, which controlled more comprehensively for comorbidity of axis I and II disorders as well as clinical, family, and treatment variables, highlight the specific negative effects of borderline personality disorder on major depressive disorder persistence.

Overall, the 7.3% recurrence rate among remitted participants is substantially lower than the relapse rates observed in the Collaborative Depression Study over 5 years (

11) and the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study over 6 years (

18). In contrast to the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study, which found that borderline personality disorder predicted shorter time to relapse, the present study found no significant predictors of recurrence except for gender and family history of depression. This discrepancy may reflect, in part, the intensive weekly tracking of the symptoms of major depressive disorder in the personality disorders study compared with the one-time retest in the present study. Alternatively, the discrepancy may reflect differences in major depressive disorder severity between general population and clinical samples (

19).

Our findings should be interpreted with consideration of the study's strengths and potential limitations. Strengths include epidemiological sampling to obtain a large nationally representative study of adults with major depressive disorder ascertained independently of treatment seeking; use of reliable and standardized measures; high retention rates over a 3-year follow-up period; consideration of both persistence and recurrence as outcomes; and multivariate analyses controlling for a comprehensive set of potential predictors. Potential limitations are reliance on data obtained with structured interviews administered by trained lay interviewers rather than trained clinicians; reliance on only one follow-up time point 3 years later (i.e., additional waves over a longer follow-up period may have allowed more observations of recurrences); focus on DSM-IV categorical personality disorder diagnoses (i.e., alternative dimensional models were not tested); and three personality disorders assessed in wave 2. While our impairment analyses supported the validity of the personality disorder diagnoses regardless of the timing of their assessment, the design introduced the small possibility that the timing of the assessments might have affected the results.

In summary, our findings support the growing clinical literature on the negative prognostic effects of personality disorders on the course of major depressive disorder and extend these data to a nationally representative sample of adults unselected for treatment seeking. Our primary finding was that borderline personality disorder significantly and robustly predicted persistence, even after controlling for other potentially negative prognostic indicators. The results suggest the need to assess personality disorders in depressed patients for consideration in both prognosis and treatment (

40).