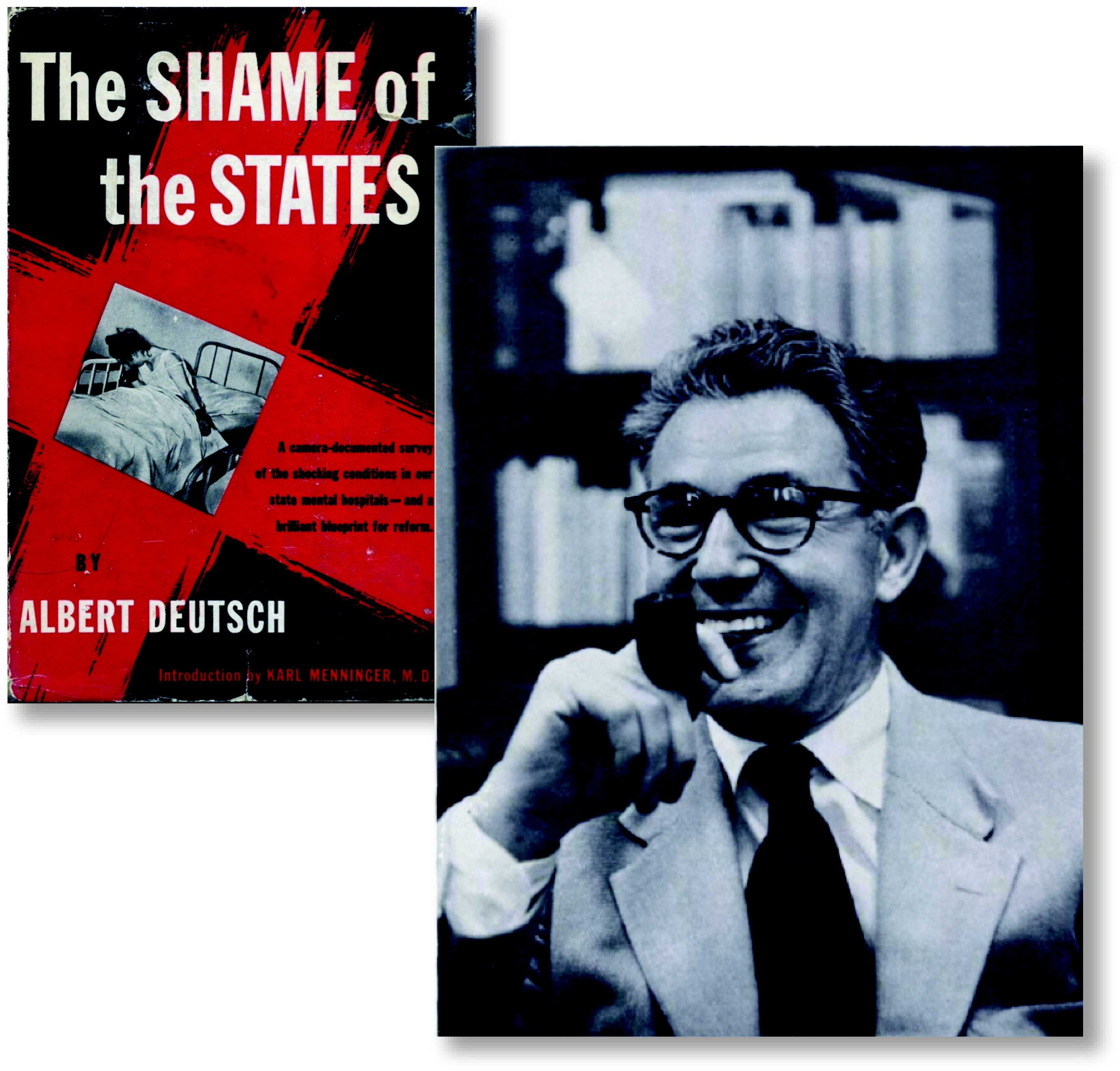

Fifty years ago the mental health community lost a great friend and advocate. Known as a crusading journalist (

1), Albert Deutsch published exposés of America's public psychiatric hospitals in the New York newspaper PM in the 1940s. The shocking descriptions, accompanied by photographs intended to sensitize readers to the conditions of citizens with chronic mental illness, were republished in his 1948

The Shame of the States (

2). Already a historian noted for

The Mentally Ill in America (

3), Deutsch was unrelenting in his quest for improved conditions for individuals with little voice of their own. Among his last contributions was editing the

Encyclopedia of Mental Health (

4). An unfinished project, “The Quest for Mental Health,” resides in the APA Archives.

An Honorary Fellow of APA, Deutsch was unflinching in the face of opposition from institutions and agencies, ruffling many a feather as an investigative reporter. In his attempts to expose substandard care of veterans in 1945, he was praised by his colleagues and vilified by Congress for his 50 news articles on the inadequacies of Veterans Administration care. Later Congress reinstated his good name.

Having exposed the evils of institutional care, Deutsch pressed for reform, but he conceded that the system needed to be dismantled. By the end of his life it had become apparent that economics, psychopharmacology, and public opinion had given rise to a rights-oriented approach to mental health. Addressing the Senate on the status of the mentally ill shortly before his death, he began, “I share with many of my fellow citizens a deep sense of gratification that this splendid subcommittee is now turning a powerful search-light on one of the darkest and most shameful areas of public neglect. As historian, journalist, and citizen, I have been actively interested in the plight of the institutionalized mentally sick for a quarter century. With many others, I have been picking at the public conscience in their behalf, relying mainly on medical, economic, moral, and humanitarian persuasion. Now…[a] more effective instrument of reform comes to hand—the demand for constitutional protection, for basic justice guaranteed to every American citizen not as a matter of mere charity or sympathy, but of inalienable right” (

5).

Though some viewed him as a “muckraker,” psychiatry understood Al Deutsch as the voice of conscience and standard bearer for values of decency, liberty, and equality. If it required his shaming of legislatures to get them to reevaluate their priorities, he was willing to take the heat. His contributions and those of countless others bore fruit when President Kennedy signed into law the Mental Retardation Facilities and Community Mental Health Centers Construction Act of 1963 (Public Law 88-164). Though he did not live to witness it, he was undoubtedly among the prime movers of the reform he fought so hard to bring about.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks APA Librarian Gary McMillan for access to the Deutsch Archive and Edward K. Silberman, M.D., for suggestions on the manuscript.