In their classic paper on diagnostic validity, Robins and Guze (

1) commented that a change in diagnosis in follow-up studies provides compelling evidence about diagnostic heterogeneity. Shifts in diagnosis mean that reliance on the initial categorization could lead to biased estimates of risk factors, familial aggregation, and prognosis (

1–

4) as well as misjudgments about optimal treatment (

5). Prospective studies of systematically diagnosed patients with first-episode psychosis have found that by 5-year follow-up, initial diagnoses of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder were retained by 80%–90% of patients (

3,

6,

7), but other diagnoses, such as major depression with psychosis, drug-induced psychosis, and schizophreniform disorder, were frequently revised, suggesting substantial misclassification (

7,

8–

17).

Little is known about the diagnostic stability of psychotic disorders beyond 5 years or the temporal stability of the follow-up diagnoses. The World Health Organization's Determinants of Outcome of Severe Mental Disorders (DOSMeD) first-contact study (

18) suggested that agreement continues to erode with increasing time from initial diagnosis. In that cohort, 12.8% of patients had shifted out of the ICD-10 schizophrenia spectrum 13 years later, and 7.5% had shifted in, for an overall kappa value of 0.43. The Nottingham DOSMeD site found better agreement for DSM-III-R diagnoses (kappa=0.60), with all patients who were initially diagnosed with schizophrenia retaining the diagnosis (

19). Preliminary analyses of the Suffolk County Mental Health Project (

20) revealed a similar level of agreement between baseline and 10-year follow-up diagnosis of schizophrenia (kappa=0.52). Similarly, long-term studies of mood disorders have reported substantial shifting from major depression to bipolar disorder and to schizophrenia (

21–

25). Since these studies compared diagnoses at two points in time, it is unknown how many times the diagnosis may have shifted before becoming stable.

Information about the determinants of short- and long-term diagnostic shifts is limited. The key determinant involves the evolution of the disorder, since diagnosis is based on the presence or duration of specific symptoms and/or on decline in functioning (

7,

18,

26).

In this study, we used a heterogeneous first-admission sample with psychotic disorders reassessed over a period of 10 years to examine the stability of five broad diagnostic categories: schizophrenia spectrum disorders, bipolar disorder with psychotic features, major depression with psychotic features, substance-induced psychosis, and other psychotic conditions (primarily psychosis not otherwise specified). Diagnoses were formulated by consensus at baseline and at 6 months, 2 years, and 10 years (

20). We specifically evaluated the distributions, stability, and trajectories of these diagnostic categories; the associations of changes in symptom severity and treatment with changes in diagnosis; and the ability of early clinical features to forecast the diagnostic changes.

Method

Design

The research reported here is from the Suffolk County Mental Health Project, a naturalistic study of the course and outcome of psychotic disorders. The sampling frame consisted of consecutive first admissions with psychosis to the 12 psychiatric inpatient facilities in Suffolk County, N.Y., from 1989 to 1995. To be included in the study, patients had to be in their first admission or have had their first admission within the previous 6 months, have clinical evidence of psychosis (any positive symptoms or use of antipsychotic medication), be in the range of 15–60 years of age, have an IQ >70, speak English, and have no apparent general medical conditions that would cause their psychotic symptoms.

The study was approved annually by the Committees on Research Involving Human Subjects at Stony Brook University and the institutional review boards of participating hospitals. Treating physicians determined capacity to provide consent. The head nurse or social worker referred potentially eligible patients to the study. Written consent was obtained from adult participants and from parents of patients under age 18.

Face-to-face assessments were conducted by master's-level mental health professionals at baseline and at follow-ups at 6 months, 2 years, and 10 years. Medical records and interviews with informants, usually family members, were obtained at each assessment.

Sample

We initially interviewed 675 participants (72% of referrals), of whom 628 met the eligibility criteria. Forty-two participants died during the 10 years. Of the remaining 586 participants, 470 (80.2%) were successfully contacted at the 10-year follow-up and comprise the analysis sample. For the 116 who were not included in the analysis, the reasons were as follows: declined, N=61; could not be traced, N=36 (including nine who left the country); had uncooperative relatives, N=10; and lacked the capacity to provide consent, N=9.

Diagnosis

At baseline, month 6, and year 2, we administered the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID), and at year 10 we administered sections of the SCID for DSM-IV (

27). Follow-up SCIDs covered the interval from last assessment. The interviewers were aware of previous SCID information. The depression module was administered without skip-outs. We inserted items about severity of suicide attempts and aggression. SCID symptom ratings integrated interview data, medical records, and information from significant others. The SCID trainer observed 5%–10% of interviews. Average interrater agreement between interviewers and the SCID trainer for the baseline, 6-month, and 2-year assessments was good, with intraclass correlations of 0.75 for psychotic symptoms and 0.78 for negative symptoms and a kappa value of 0.73 for depressive symptoms; for the 10-year assessment, the corresponding statistics were 0.81, 0.87, and 0.79, respectively (

28–

30).

The primary study diagnosis was determined by consensus. At baseline, two psychiatrists independently completed the SCID diagnosis module; inconsistent diagnoses, occurring for <10% of participants, were reviewed by a third psychiatrist (

13). At follow-up, at least four psychiatrists formulated best-estimate longitudinal consensus diagnoses from information accumulated over time (except prior research diagnoses), including the interviewers' narratives (

7,

20). If consensus was not reached or the diagnosis did not fit a DSM category, the diagnosis was coded as unknown, which was included in the “other” category. In the various assessments, the proportion of diagnoses coded as unknown was 12.8% at baseline (60/470), 4.0% at the 6-month follow-up (19/438), 1.7% at the 2-year follow-up (8/459), and 0.9% at the 10-year follow-up (4/470).

As noted, baseline diagnoses were based on DSM-III-R and follow-up diagnoses on DSM-IV. Although DSM-III-R and DSM-IV criteria varied somewhat, a review of 6-month diagnoses using both criteria sets indicated that for the broad categories considered here, the differences were negligible (at the 6-month follow-up, only four DSM-III-R diagnoses were revised under DSM-IV).

Clinical and Treatment Variables

Eight clinical ratings were obtained at each assessment: 1) negative symptoms, based on the sum of 18 items from the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS;

31), excluding inattentiveness during mental status testing; 2) psychotic symptoms, based on 16 items on delusions and hallucinations from the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS;

30,

32); 3) disorganized symptoms, based on 13 SAPS items on bizarre behavior and thought disorder; 4) depressive symptoms, based on the sum of nine SCID past-month depressive symptoms; 5) mania severity, based on the excitement item of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS;

33); 6) suicide attempts (lifetime at baseline; past interval at follow-up); 7) aggression, based on violence toward people or property (rated 1=never to 5=frequent); and 8) Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) score for the best month in the year before baseline and year 10 and in the interval between assessments at month 6 and year 2.

Treatment variables included rehospitalization during follow-up intervals; antipsychotic, antidepressant, and antimanic medication use at each contact; and substance abuse treatment in the previous 6 months. There was good agreement between self-report and medication information in outpatient records (

34).

Statistical Analysis

Agreement of earlier diagnoses with diagnosis at year 10 was examined using kappa, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, sensitivity, and specificity.

Symptom and treatment determinants of shifts in diagnosis were examined using mixed-effects logistic regression (

35) estimated in SAS, version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.), with PROC NLMIXED. The time-varying symptom composites and treatment variables were entered simultaneously into separate regression models examining changes in each diagnostic category (coded 1=present, 0=absent). Continuous variables were standardized with respect to their grand means and standard deviations (across all patients and follow-up points) to facilitate interpretation. Slopes of independent variables and the intercepts were random terms in order to model associations for each participant. Time was modeled as a categorical variable to control for average changes in the dependent and independent variables across assessments. The random-effects covariance structure was specified as an unstructured covariance matrix.

We then tested whether the variables that were significant in the mixed-effects logistic regression models predicted subsequent shifts in diagnosis. Using structural equation modeling with Mplus, version 5.1 (

www.statmodel.com), we specified cross-lagged models in which the follow-up diagnostic status was predicted jointly by diagnostic status and participant characteristic from the preceding assessment point (see Figure S1 in the online data supplement that accompanies the online edition of this article). In evaluating the models, we examined the comparative fit index, the Tucker Lewis index, and the root mean square error of approximation (

36).

Missing data were addressed in structural equation modeling using the full information maximum likelihood method (

37), which estimates models from all available data, thus minimizing attrition-related biases. An analogous approach was employed in mixed-effects logistic regression so that data from each participant were included in the analysis. The longitudinal analyses were based on 1,837 observations from 470 participants.

Results

Sample Characteristics

About half of the 10-year follow-up sample was male (57.2%), under age 28 at baseline (50.4%), and from blue-collar households (47.4%) (

Table 1). Three-quarters (74.3%) were Caucasian. At baseline, nearly half (46.4%) had lifetime episodes of major depression. One-fifth (21.3%) had a history of frequent or serious aggression.

Compared to nonparticipants, the 10-year follow-up cohort had poorer baseline SANS and GAF ratings, and a greater proportion came from blue-collar households (

Table 1). No other significant differences were found, including in baseline research diagnoses.

Distribution and Stability of Diagnosis

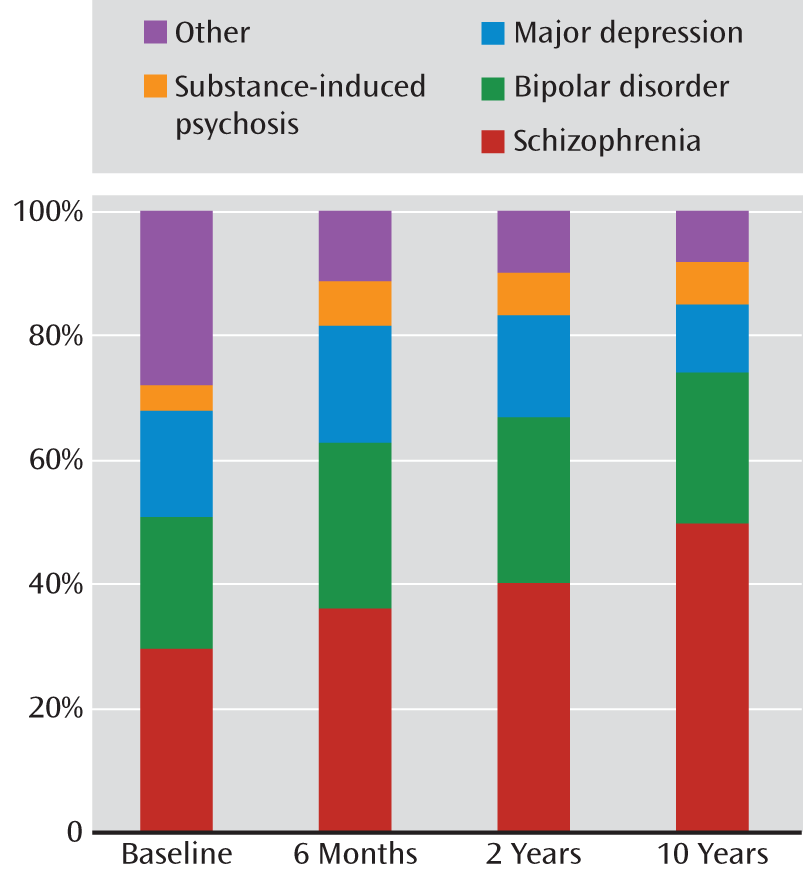

The proportion diagnosed with schizophrenia spectrum disorders increased progressively from 29.6% of the sample at baseline to 49.8% at year 10 (

Figure 1). The proportion with schizophrenia increased from 20.9% at baseline to 38.1% at year 10, and the proportion with schizoaffective disorder increased from 3.4% at baseline to 11.5% at year 10. In contrast, the proportion with schizophreniform disorder decreased from 5.3% of the sample at baseline to 0.2% at year 10. Eighty percent of participants with schizophreniform disorder at baseline were later rediagnosed with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Similar proportions were diagnosed each time with bipolar disorder (21.1% at baseline and 24.0% at year 10) and substance-induced psychosis (4.5% at baseline and 7.0% at year 10). The proportion with major depression fell from 17.0% at baseline to 11.1% at year 10, and other disorders decreased from 27.9% at baseline to 8.1% at year 10.

Agreement of baseline with 10-year diagnosis was low, with kappa values ranging from 0.13 to 0.65 (

Table 2), but the reasons for this inconsistency varied. A diagnosis of schizophrenia showed relatively low negative predictive value and sensitivity but high positive predictive value, indicating low false positive and high false negative rates. In contrast, bipolar, major depressive, and substance use disorders showed relatively weak sensitivity and positive predictive values (prospective consistency), indicating high false negative and false positive rates. The same was true for other psychotic disorders, except that the false negative and false positive rates were higher. Agreement improved over time, with kappa values for 2- to 10-year comparisons ranging from 0.69 to 0.76, except for other psychotic disorders (kappa=0.45).

Patterns of Diagnostic Shifts

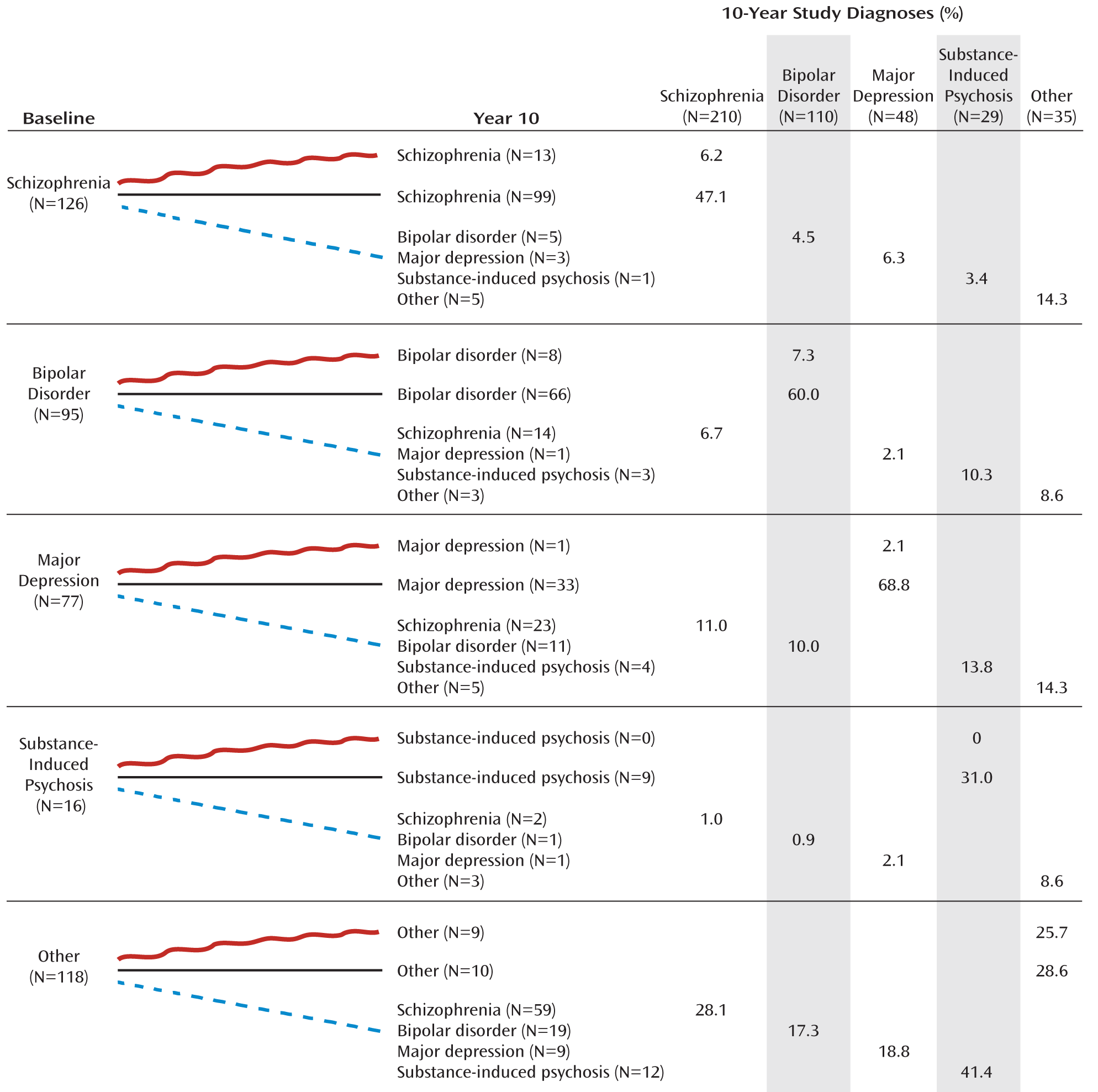

To examine the patterns of diagnostic shifts, we focused on the 432 participants who received a research diagnosis at all four assessment points (

Figure 2). For each baseline category, we traced the number of participants who received the same diagnosis each time; the number who received the same baseline and 10-year diagnosis but a different diagnosis at 6 months and/or 2 years; and the number who received a different diagnosis at year 10. Only 49.3% (213/432) retained their original diagnosis each time. Participants who were initially diagnosed with schizophrenia were most likely to retain the diagnosis throughout the follow-up period (78.6%, 99/126), followed by bipolar disorder (69.4%, 66/95), substance-induced psychosis (56.3%, 9/16), and major depression (42.9%, 33/77). Only a small proportion (8.5%) remained in the “other” category.

The largest proportion of diagnostic shifts was from non-schizophrenia diagnoses to schizophrenia. Among 306 participants with a non-schizophrenia diagnosis at baseline, 98 (32.0%) were eventually diagnosed with schizophrenia, with one-third of these shifts (36/98) occurring after year 2. Shifts from mood disorders were primarily to schizoaffective disorder (15/23 from major depression, 8/14 from bipolar disorder). The second largest shift was to psychotic bipolar disorder, involving 10.7% of participants with a non-bipolar diagnosis at baseline (36/337); one-third of them (12/36) occurred after year 2. Eleven participants with baseline major depression (14.3%) switched to bipolar disorder, half of them (5/11) after year 2.

The right half of

Figure 2 shows the composition of the 10-year diagnostic groups relative to these trajectories. In descending order of diagnostic stability, 68.8% of participants with major depression at 10-year follow-up had received the same diagnosis since baseline, followed by bipolar disorder (60.0%), schizophrenia (47.1%), substance-induced psychosis (31.0%), and other disorders (28.6%).

Determinants of Diagnostic Changes

Mixed-effects logistic regression was used to examine the changes in the clinical picture and treatment exposures that contributed to changes in diagnosis. Given the number of comparisons, we focus on findings with p values <0.01 (

Table 3).

The shift to schizophrenia was more likely to occur when there was a decrease in GAF score and depressive symptoms, an increase in negative and psychotic symptoms, and initiation or reinstatement of antipsychotic medications. Shifts to psychotic mood disorders were associated with improvement on the GAF, increased depressive symptoms, and decreased negative and psychotic symptoms. Improvement on the GAF was particularly pronounced for a shift to bipolar disorder, and an increase in depressive symptoms was especially important for a shift to major depressive disorder. The change to bipolar disorder was also associated with an increase in excitement ratings and with initiation or reinstatement of mood stabilizers. A change to major depressive disorder was preceded by initiation or reinstatement of antidepressants and discontinuation of mood stabilizers. Rediagnosis to substance-induced psychosis followed initiation or reinstatement of substance abuse treatment.

Antecedents of Diagnostic Shifts

To determine whether we could forecast changes in diagnosis, we selected the significant variables from the mixed-effects logistic regression models and constructed 18 models using structural equation modeling. These models showed reasonably good fit (

Table 4). For schizophrenia, poorer ratings on the GAF, SANS, and SAPS predicted shifts into this category from baseline to month 6 and from year 2 to year 10, but none predicted a shift from month 6 to year 2. For bipolar disorder, better GAF scores, lower SANS scores, lower depression ratings, and greater excitement ratings, as well as treatment with antimanic medication, antedated shifts from baseline to month 6. The first three also predicted the shift from year 2 to year 10, but only treatment with antimanic medication forecast the shift from month 6 to year 2. For major depression, increased depressive symptom ratings, lower SAPS score, use of antidepressants, and no use of antimanic medication predicted a shift from baseline to month 6. None of the selected variables predicted later shifts. For substance-induced psychosis, substance abuse treatment predicted a shift from baseline to month 6, but not at later intervals.

Discussion

We examined diagnostic stability in a first-admission cohort across four assessments over a 10-year period. We previously found considerable shifting from baseline to the 6-month and 2-year follow-ups, most notably from major depression and psychotic disorders in the “other” category to schizophrenia (

7,

13). In the present study, we found a substantial number of revisions at the 10-year follow-up, including 20.7% whose diagnosis changed from year 2 to year 10. Only half of the cohort retained the same diagnosis throughout the study. Changes in symptoms and treatment were important determinants of shifts in diagnosis. The observed effects were fully consistent with expectations, except that disorganized symptoms and rehospitalization were largely unrelated to change in diagnosis. Furthermore, some diagnostic changes could be anticipated. Participants who did not meet criteria for schizophrenia but exhibited poor functioning and greater negative and psychotic symptom ratings were likely to shift into that category, whereas better functioning and lower negative and depressive symptom ratings predicted a later shift to bipolar disorder.

Our findings must be viewed within the context of the limitations of the study. First, our sample consisted of patients who were hospitalized with psychotic symptoms, and the results may not generalize to patients who were never hospitalized or did not have co-occurring psychosis. Second, the substance-induced psychosis and major depression groups were small, and thus the modeling analyses were able to detect antecedents only for the shift between baseline and the 6-month follow-up, when changes were more common. Third, our measure of mania severity (the BPRS excitement item) was crude. Our study began with a focus on schizophrenia and was designed to minimize exclusion of false negatives. We later realized that many participants had a primary mood disorder. Starting at the 2-year follow-up, we added a mania rating scale. Fourth, DSM-IV was published as we were completing the 6-month diagnoses. We updated all of the 6-month diagnoses but were unable to recheck the baseline diagnoses. However, only four 6-month diagnoses warranted a change. The fact that the shifts occurred across the 10-year period and were not limited to the period from baseline to the 6-month follow-up also suggests that the adoption of DSM-IV is not the primary explanation for our findings. Fifth, our diagnoses were formulated by consensus, which precluded examining interrater (psychiatrist) agreement. Sixth, we do not know precisely when during the 2- to 10-year follow-up period the diagnostic team would have concluded that a change in diagnosis was warranted. Lastly, the interviewers and psychiatrists had access to multiple longitudinal sources of information and were blind only to prior research diagnoses. Diagnoses established in this fashion are not comparable to diagnoses determined by clinical judgment or cross-sectional SCID ratings. However, longitudinal information is essential to most diagnoses, and we wished to improve the accuracy of the consensus diagnosis with the best possible chronological record of the evolution of the disorder. If anything, having access to longitudinal information should have led the research psychiatrists to maintain the same diagnosis without clear evidence to the contrary. All in all, the diagnostic instability reported here should be regarded as a best-case scenario.

We could not locate any previous studies that considered serial research diagnoses in samples of patients with psychosis. However, studies have examined serial clinical diagnoses in treatment samples (

38,

39). These studies also report temporal variability in diagnosis, with schizophrenia having the best agreement and personality disorders the worst.

Changes in diagnosis may have a number of explanations. By definition, some diagnoses, such as schizoaffective disorder, require specific temporal patterns of symptoms. Other diagnoses, such as bipolar disorder, include episodes with different polarities that take time to unfold. Many symptoms, such as social withdrawal and agitation, may be present in more than one disorder. In terms of psychotic symptoms, none is pathognomonic of a specific diagnosis. At the time of initial presentation, there are often gaps or ambiguities in the information available to establish a diagnosis. In addition, we included participants with significant histories of substance use to construct a generalizable sample, and this too may have confounded the clinical presentation and ultimately the diagnoses. Events occurring just before an acute decompensation may be red herrings when viewed in the context of the overall illness course and take on undue weight in the initial diagnosis. Thus, it is not surprising that the likelihood of a shift in diagnosis with longitudinal assessment is greatest among first-episode patients.

Our results demonstrate that diagnostic reconsideration is often linked to changes in functioning or in symptoms. In addition, we found that changes in medication regimens administered by community physicians forecast shifts in diagnosis. Although at first glance this may seem tautological, the treatments administered by community physicians could also reflect their awareness of diagnostically important symptoms, even when the symptoms are subsyndromal or at low to moderate levels of severity. This raises the possibility that strict adherence to the diagnostic criteria may have led us to miss clues utilized by practitioners and misjudge the illness initially. There is obviously a tension between strict implementation of diagnostic criteria, in which equal weight is given to all of the components, and community diagnoses that consider some symptoms and behaviors to be more salient than others. Nevertheless, if we regard our 10-year diagnoses as the gold standard, then half of the study population was misclassified in our initial rigorous application of DSM criteria. This is a very concerning finding given that treatments (with their associated side effects) are recommended long term based on presumptive diagnoses that our data suggest have a 50-50 chance of being revised. Misclassification also has serious implications for research by promoting nonreproducible results and potentially erroneous conclusions across a broad range of studies (e.g., therapeutic indications and outcome predictors; biomarkers; genetics; and etiologic factors of specific disorders).

DSM-III and subsequent revisions have been celebrated for introducing a reliable system of classification. Yet most assessments of diagnostic reliability have focused on interrater reliability at a given point in time rather than on the temporal reliability of initial and subsequent diagnoses determined from prospective research. Our results make it clear that a reliable cross-sectional diagnosis may still have poor reliability over time. Conceivably, representative samples, as opposed to participants in clinical trials, include many patients who do not have classic clinical presentations. Development of future criteria for psychiatric diagnosis will need to give greater consideration to temporal reliability and predictive validity, rather than cross-sectional reliability.

Robins and Guze (

1), writing before publication of DSM-III, were prescient in drawing attention to the fundamental importance of longitudinal diagnosis for both research and clinical care. Our results, along with those of a recent study of mood disorders (

26), reinforce the importance of reassessing diagnosis over the long term. As the product of a naturalistic study, our findings highlight the complexity of formulating a diagnosis in the face of multiple comorbidities (e.g., mood symptoms, psychotic symptoms, and substance use). They also emphasize the clinical significance of judiciously integrating longitudinal information from multiple sources. Finally, these findings underscore the need to periodically reevaluate clinical diagnoses to ensure that patients are receiving appropriate interventions.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the participants and mental health community of Suffolk County for contributing their time and energy to this project. They are also indebted to the interviewers for their careful assessments and to the psychiatrists who contributed to the consensus diagnoses: Alan Brown, Eduardo Constantino, Thomas Craig, Frank Dowling, Shmuel Fennig, Silvana Fennig, Beatrice Kovasznay, Alan Miller, Ramin Mojtabai, Bushra Naz, Joan Rubinstein, Carlos Pato, Michele Pato, Ranganathan Ram, Charles Rich, and Ezra Susser. They also thank Janet Lavelle and Al Hamdy for coordinating the study.