Knowledge of morbidity risks and optimal treatment of women with major psychiatric illnesses during pregnancy, at childbirth, and during the postpartum period is strikingly limited, particularly with major affective disorders (

1–

8). Such knowledge is clinically important given the considerable complexities of clinical management of affectively ill women during perinatal periods (

9,

10). These complexities include the need to balance potential teratogenic and other adverse effects of medication on the offspring against the consequences of acute and potentially life-threatening untreated maternal illness, the impact of the illness on families, and the potential adverse effects of acute maternal illness on fetal and neonatal development (

9–

12). Despite their potential clinical impact, many cases of perinatal mood disorder go undiagnosed and untreated (

5,

13).

A link between childbirth and psychiatric illnesses has been recognized clinically for centuries, including many observations of a strong association of major affective and psychotic episodes in the puerperal period (

1,

14–

17). Several epidemiologic studies suggest that pregnancy itself may not be associated with major elevations in risk of affective illness compared to periods unrelated to pregnancy, or even suggest a lower risk during pregnancy both in the general population and among women with a unipolar major depressive disorder (

1,

2,

4,

5,

13). There is also uncertainty regarding the relative risks of illness episodes in women diagnosed with a bipolar disorder during pregnancy compared with during nonpregnant periods, but the early postpartum period is strongly associated with an elevated risk of major affective or psychotic episodes in association with bipolar disorders (

1,

3,

5,

8,

18–

26).

Most but not all studies involving clinical samples of women with identified mood disorders suggest that pregnancy and the postpartum period may be destabilizing, although rates of illness range widely, from 5% to 100%, usually with average risks somewhat higher soon after childbirth than during pregnancy (

2,

3,

7,

18–

26). As expected, reported risks of affective, especially depressive, symptoms or “blues” during pregnancy or the postpartum period are several times greater than those for major depressive episodes (

2,

4,

5). Illness during pregnancy appears to be mainly depressive or dysphoric (including mixed states) in bipolar disorder and depressive in unipolar disorders. Risk is not only probably greater during the postpartum period than during pregnancy, but also much greater after discontinuing antidepressant or mood-stabilizing treatment (

3,

6,

7). The timing of occurrences of mood disorders during pregnancy has, somewhat inconsistently, been associated with the early months of pregnancy, and discontinuation of maintenance treatment has been associated with greater risk in the first than in later trimesters (

3,

6–

8). Clinical features of postpartum affective illness appear to differ little from illness episodes unrelated to pregnancy (

25–

28), although an association of bipolar disorder with postpartum psychotic disorders as well as mania, mixed states, or depression has been emphasized (

1,

3,

9,

17,

25). It is also becoming clearer that affective symptoms during pregnancy among women with either bipolar or unipolar disorders are strongly associated with continued or new postpartum morbidity, by perhaps as much as 10 times more than without affective illness during pregnancy (

2,

3,

14,

23,

25,

29).

Surprisingly, direct comparisons of risks of specific types of episodes across the range of major affective disorders are rare (

14,

15). The need for quantitative estimates of risks of particular types of affective episodes during and following pregnancy in women with known or later diagnosed major affective disorders was a primary impetus for the present study. Our aims were 1) to compare rates of specific forms of affective episodes between pregnancy and the postpartum period and among women diagnosed with types I or II bipolar disorder or with unipolar depression, and 2) to identify potential risk factors among selected clinical and demographic measures for illness episodes during pregnancy and in the postpartum period. Based on previous studies (

1–

9,

14,

15,

20–

26), we hypothesized that 1) perinatal risks of episode occurrence would be mainly depressive with bipolar as well as unipolar disorders, 2) risks would be greater soon after childbirth than during pregnancy, and 3) patients diagnosed with bipolar I and II disorders would have similar perinatal risks, both greater than with unipolar depression.

Method

Methods of diagnostic and clinical assessment and computerized record-keeping followed at the study sites have been reported previously (

3,

7). Data were collected systematically at the perinatal psychiatry programs at Massachusetts General Hospital (Boston) and the Lucio Bini Mood Disorders Centers (Cagliari [Sardinia, Italy] and Rome) from 1980 to 2010, after referrals by clinicians for specialized clinical assessment and care. All participants were followed and treated clinically. They typically received single treatments or varying combinations of antidepressants, mood stabilizers, other drugs, and psychotherapy as indicated by changing clinical requirements. Study protocols were reviewed and approved by appropriate ethical review boards at the collaborating study institutions, and all participants provided written informed consent for anonymous and aggregate reporting of their clinical findings, with explicit assurance that their treatment would not be affected by study participation or protocols.

Potential study subjects were women at least 18 years of age for whom data were available for at least one completed pregnancy and who were diagnosed with DSM-IV bipolar I, bipolar II, or unipolar major depressive disorder, based on multiple expert clinical assessments and semi-structured examinations at the study centers. Primary diagnoses were updated to DSM-IV criteria between 2008 and 2010. Categorization of perinatal episode types was based on DSM-III or DSM-III-R criteria in assessments made in the 1980–1994 period, and on DSM-IV criteria thereafter. Information concerning episodes of affective illness during and after pregnancy was gathered retrospectively and then recorded in life charts, which were converted to digital databases after 2000. Illness occurrence was defined as a clinically identified episode of major depressive, manic/hypomanic, or mixed manic-depressive states or of an anxiety disorder including panic—all meeting DSM-III or DSM-IV diagnostic criteria. Periods considered in the same women included pregnancy and the postpartum period, defined as 6 months following live births to include potential effects of lactation and other stressors commonly encountered during the initial months after delivery.

Analytic Plan

Diagnostic groups were compared for frequency and types of illness episodes during pregnancy and the initial 6 months after childbirth for all pregnancies in each patient. Demographic and clinical factors, including long-term morbidity measures and number and years of pregnancies, were compared between women with and without illness occurrences during pregnancy or the postpartum period. Preliminary bivariate comparisons employed analysis of variance for continuous measures and contingency tables for categorical measures. We also compared presence and absence of selected clinical and demographic factors in association with illness episodes during pregnancy and the postpartum period, based on computed odds ratios. Incidence rates were calculated with a nominal exposure time of 0.75 years for pregnancy and a defined exposure time of 0.5 years for the postpartum period. We also used random-effects Poisson regression models to compare illness rates during pregnancy and during the postpartum period, including covariates of interest or found suggestively (with p values ≤0.10) related to illness occurrence in preliminary bivariate analyses. The threshold for statistical significance was a two-tailed alpha of 0.05, except when the Bonferroni correction was used for multiple comparisons. For statistical computations, we used Statview, version 5 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, N.C.) and Stata, version 8 (StataCorp, College Station, Tex.).

Discussion

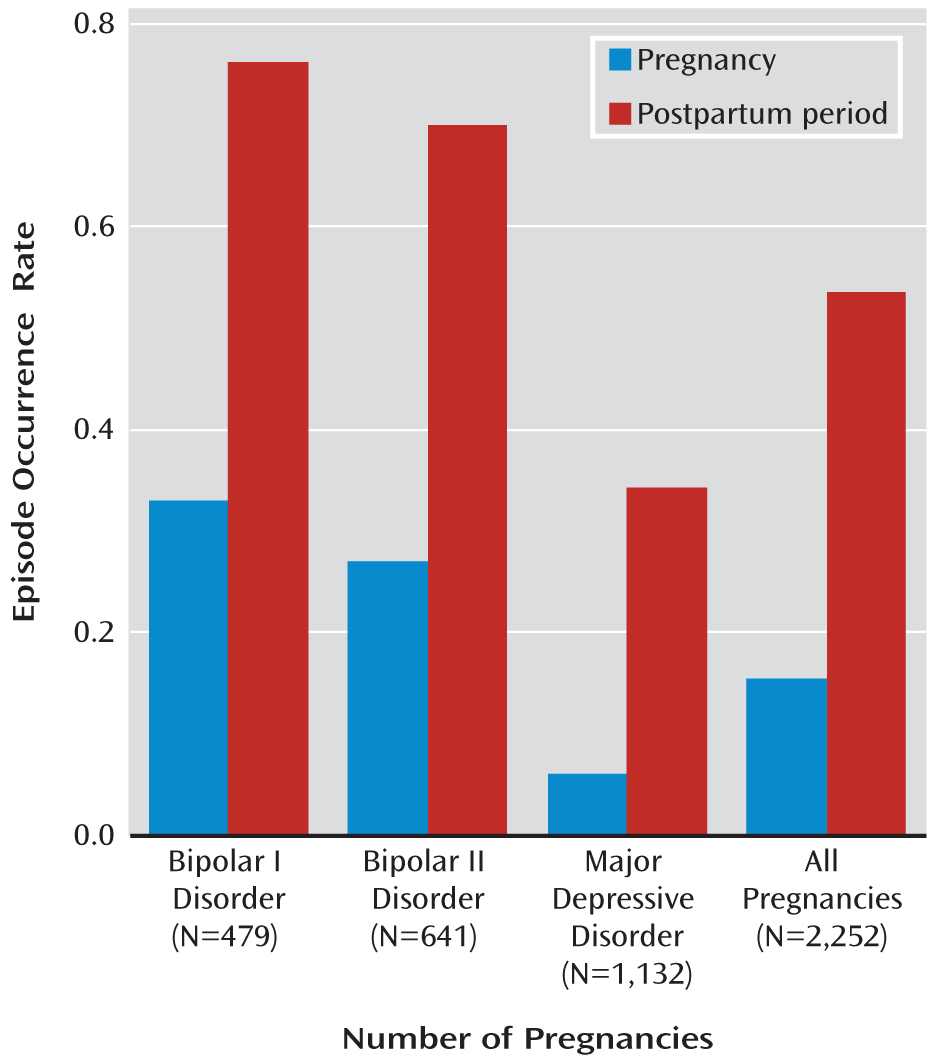

Our findings support the impression arising from clinical experience and from previous reports (

13–

25) that the perinatal periods carry substantial risks of illness episodes in women diagnosed with a major affective disorder. Overall incidence rates of illness occurrences (episodes per patient-year) were greater in patients with bipolar illness than in those with unipolar illness, although the postpartum period-pregnancy risk ratio was greater with unipolar depression (

Figure 1). These findings are congruent with reports over the past 150 years (

17) that especially high risks for episodes of major mood disorders occur in the postpartum period among women diagnosed with either unipolar or bipolar disorders (

1–

5,

13,

15,

16,

19). In the sample we studied, overall risks in bipolar and unipolar disorders were 23% and 4.6%, respectively, during pregnancy, and 52% and 30%, respectively, during the postpartum period. First-illness episodes occurred during pregnancy or the postpartum period in 7.6% of women. Although the postpartum period appears to carry major risks compared to pregnancy, it remains unclear whether pregnancy itself is stressful or protective with respect to affective illness occurrences. Resolution of this uncertainty will require well-matched—and, ideally, prospective—comparisons of episode occurrence rates and exposure times during pregnancy compared with periods unrelated to pregnancy (

12,

13).

Notably, major depression was the most prevalent form of perinatal morbidity—even among patients with bipolar disorder, who also had substantial risks of dysphoric-agitated mixed states (

Table 2). These observations accord with reports that the prevalence of depression is high in pregnant women with either unipolar or bipolar disorders (

3,

6,

7,

20,

21). In fact, the risk of affective episodes was found to be highest in the first trimester of pregnancy as early as the 1800s (

15,

17) and to decline in later trimesters, for uncertain reasons (

3,

6,

7). Moreover, a great many cases of mood disorder are overlooked and left untreated during pregnancy (

5,

13,

14). Such episodes appear to be a major risk factor for subsequent postpartum affective illness (

1,

2,

13,

20–

22,

27).

The high risk of depression in bipolar patients may not be surprising in view of the difficulty of achieving successful long-term treatment and prophylaxis for bipolar depression (

29). Although depression has been strongly associated with pregnancy in both bipolar and unipolar disorders, we expected (

15,

16) and found more mania and psychosis among patients with bipolar disorders (

Table 2). Moreover, the observed average perinatal illness risks, especially in patients with unipolar illness (

Table 1), were lower than expected from observations in some studies but within the range of widely varied reported rates (

4–

6,

12,

13).

Since patients in the present study were treated clinically, it is possible that treatments aimed at depression, which have limited long-term effectiveness in unipolar and less in bipolar disorders (

30–

32), exerted clinically destabilizing effects in patients with bipolar disorders. In addition, the metabolic clearance of psychotropic drugs can shift during pregnancy and childbirth, further complicating assessment of their potential effects (

32–

34). However, treatment discontinuation just before or at the start of pregnancy is common and may contribute to the risk of illness episodes early in pregnancy (

3,

6,

7). Understandably, potentially teratogenic treatments are most likely to be avoided early in pregnancy, making presumably protective psychiatric treatments least likely to be prescribed or accepted when most likely to be needed (

9,

10), opening up the risk of major destabilizing effects (

3,

6,

7,

35–

37).

The observed lower risk of illness occurrence in women with four or more pregnancies may reflect self-selection against further pregnancies by women who experienced illness during or after pregnancy. This inverse relationship might also reflect beneficial adjustments of treatment or better adherence to treatment over years of illness experience. In addition, younger age at illness onset was strongly associated with perinatal illnesses, especially during the postpartum period and with bipolar disorders (

Table 3). Younger onset age may be an independent risk factor reflecting a more severe natural history of some mood disorders (

38). The risk of an episode during a first pregnancy in women with bipolar disorders was greater for those whose illness onset was in 1992 or earlier, whereas postpartum episodes were more prevalent in women whose illness onset was after 1992 (

Table 3). The secular increase in risk in more recent first pregnancies may reflect greater stressful effects of pregnancy, whereas the lower postpartum risk since 1992 may arise from advances in diagnosis and treatment. In addition, being unmarried and unemployed seemed to be stressful factors with a greater impact during pregnancy than during the postpartum period.

When a clinical diagnosis of mood disorder preceded pregnancy, the likelihood of becoming pregnant was lower than when pregnancy followed diagnosis, especially with bipolar disorder, and was probably a consequence of having a mood disorder (

39). Moreover, risk of perinatal illness was greater when diagnosis preceded pregnancy. This risk was greater with bipolar disorders, evidently reflecting greater illness severity.

The bipolar I and II syndromes showed similar patterns of risk (

Table 2). This similarity is consistent with other clinical evidence (including suicide rates) that bipolar II disorder is not a less severe form of bipolar disorder (

30,

40).

Limitations to this study include the relative paucity of patients with multiple pregnancies, sampling from patients referred to specialty clinics, and the retrospective clinical ascertainment of illness episodes during most pregnancies. However, recall bias should be similar across diagnoses and for periods during and after pregnancy, even if it is greater with longer assessment delays. In addition, data on treatment status and on the severity and duration of each episode were not adequate to support analysis, and control data were not available on occurrence risks unrelated to pregnancy. Despite these possible limitations, our findings are based on a large, pooled international sample, which should limit potential effects of regional variance in case-finding and treatments. The findings provide quantitative comparisons of postpartum period and pregnancy risks for the three major affective disorders under similar conditions of assessment.

In conclusion, our findings indicate substantial risks of clinically ascertained major affective illness episodes during pregnancy and far greater risks during the postpartum period in bipolar I, bipolar II, and major depressive disorders, with a preponderance of depressive episodes overall. The highest risk of illness occurrence was found among women diagnosed with bipolar I disorder during both pregnancy and the postpartum period, and with all three diagnoses, the risk was much higher during the postpartum period than during pregnancy. Among prominent risk factors, younger age at illness onset and diagnosis before the first pregnancy were strongly associated with illness episodes in all diagnostic groups and both perinatal periods; moreover, illness during pregnancy strongly predicted illness during the postpartum period. In about one in 13 women, the first lifetime episode of major affective illness was perinatal. These findings may contribute to improved clinical management, support preventive efforts, and encourage critical assessment of the risks and benefits of particular treatments to mothers and their offspring during various phases of pregnancy and the postpartum period.