The patient was a 25-year-old single Caucasian Marine veteran with a history of three deployments in Iraq (21 months total), where he engaged in reconnaissance duties and served as a gunner. While on a mission, the patient witnessed the shooting of a close comrade by sniper fire. He assisted in providing medical care to his wounded comrade, who died in the patient's arms while en route to a hospital. After returning to the United States, the patient experienced daily intrusive memories and nightmares about the shooting. He avoided crowds and social situations, engaged in heavy alcohol use, and grew distant from his family and friends. He reported severe hyperarousal in crowded stores and became physically violent in situations where he felt provoked.

Treatment and Progress

The following measures were used for diagnostic assessment and to monitor progress: the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (

1) to assess psychiatric diagnoses; the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) (

2) to assess PTSD diagnosis and symptoms; the PTSD Checklist–Military Version (

3) for weekly monitoring of PTSD severity; the Beck Depression Inventory, 2nd edition (BDI) (

4), for weekly assessment of depressive symptoms; the timeline follow-back method (

5) to monitor self-report daily use of substances; urine drug screens to assess illicit drug use; and breath alcohol tests to assess recent alcohol use. Throughout treatment and follow-up, an independent assessor administered the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview, the CAPS, and the timeline follow-back.

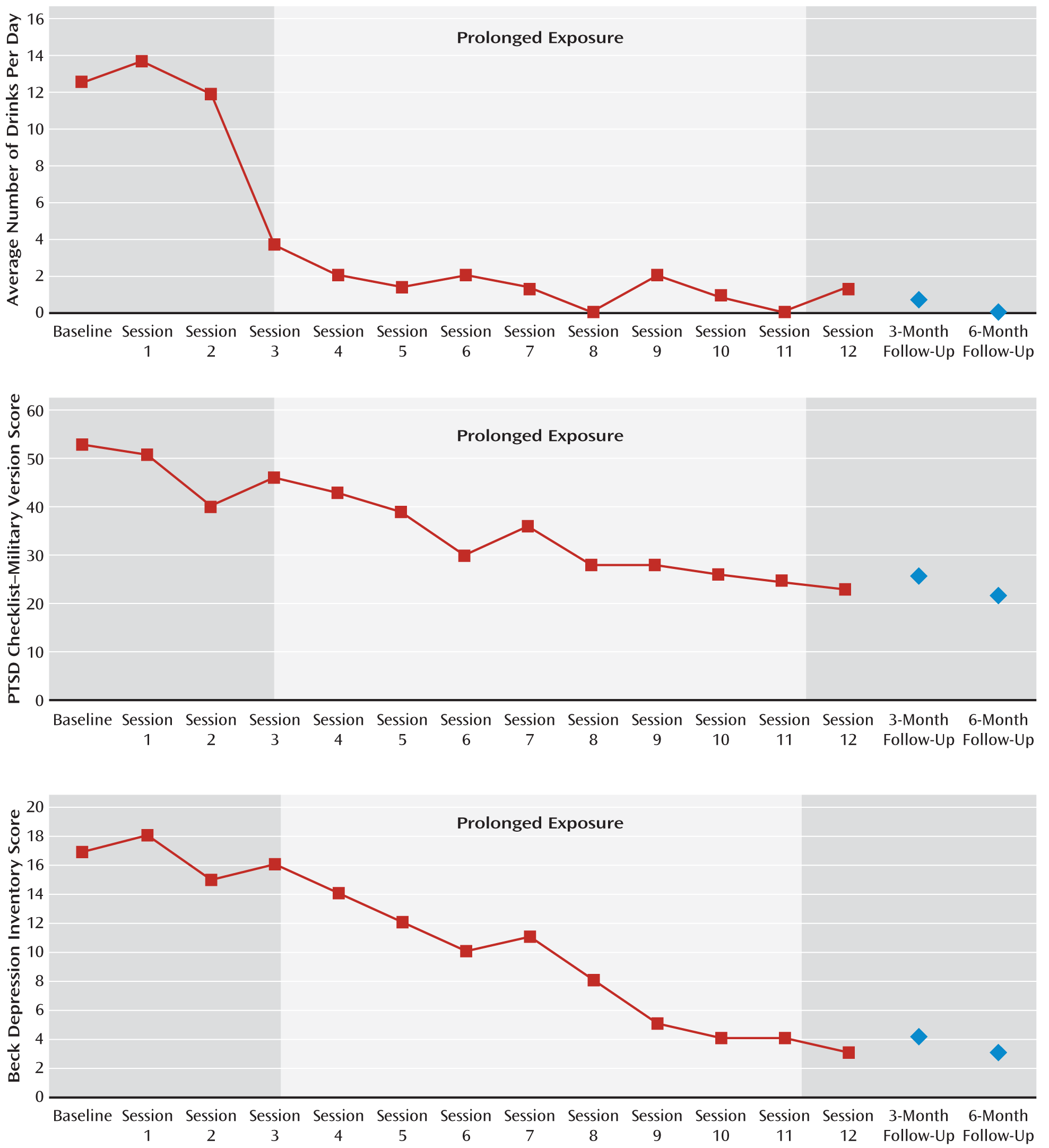

At baseline, the patient scored in the clinical range for PTSD (CAPS score=71; PTSD Checklist score=53), exhibited mild depression (BDI score=17), had a positive breath alcohol test, and consumed approximately 12.5 beers per day on 50/60 days (83.3%) prior to baseline.

The patient was treated with an integrated, exposure-based PTSD/substance use disorder psychotherapy called “COPE” (

concurrent treatment of PTSD and substance use disorders using

prolonged

exposure). COPE consists of 12 individual 90-minute sessions that integrate relapse prevention for substance use and prolonged exposure for PTSD. Each session consisted of a substance use and a PTSD treatment component. In the first 30 minutes of each session, the clinician evaluated the patient's alcohol consumption since the last session, assessed high-risk situations encountered, and discussed techniques for managing cravings. In session 1, the patient's identified goal was to reduce alcohol consumption from 12.5 to 5.0 standard drinks per day, 3 days per week. Sessions 2 and 3 focused on learning skills to manage cravings and thoughts about using alcohol. The patient's alcohol use frequency and severity diminished markedly by session 3 (

Figure 1) and remained low through the 3-month follow-up. All urine drug screens and breath alcohol tests after baseline were negative.

During the remaining 60 minutes of each session, PTSD was addressed. In sessions 1–3, education on fear and avoidance, the rationale for concurrent treatment, breathing retraining (a relaxation exercise), and the rationale for in vivo and imaginal exposures were provided. In session 3, the clinician and patient constructed an in vivo hierarchy comprising safe situations that the patient had been avoiding. The patient selected two in vivo exposures to complete each week, starting with situations that provoked a moderate amount of subjective discomfort (e.g., going to a movie theater, calling a friend), gradually moving up to situations associated with greater discomfort (e.g., going to a crowded festival). As a result of engaging in the in vivo exposures, the patient was able to visit family, develop new friendships, engage in social activities, and begin dating again. The use of in vivo exposures in patients with co-occurring substance use disorders requires careful assessment. Situations that increase exposure to substances or have a high probability of inducing craving are not included in the hierarchy. For example, going to a bar where the patient previously drank alcohol would not be a safe in vivo exposure assignment. Patients must be instructed not to use any substances before, during, or immediately after engaging in exposures. Alcohol use in this context would represent a “safety behavior” that would dilute the exposure's therapeutic effects.

Imaginal exposures (sessions 4–11) consisted of repeatedly recounting the memory of the shooting, in the present tense, with eyes closed, for 30–45 minutes. This was followed by approximately 10 minutes of processing and of discussing the thoughts and feelings that came to mind during the imaginal exposure. Starting in session 8, “hot spots” (the most distressing parts of the trauma memory) were repeated. Finally, in session 11, the entire memory was revisited. The patient listened to a recording of the imaginal exposure each day and reported that this daily exercise helped him to do the imaginal exposures in session. Processing focused primarily on the patient's feelings of guilt in two areas: 1) his belief that he should have been able to prevent his comrade's death by locating the enemy sniper ahead of time and 2) his belief that he should have been the one who was killed, not his comrade. Through a series of questions (e.g., “What did you do differently than what you were trained to do?” and “How would it have made it any better had you been the one killed?”), the patient was able to realize that he did everything he was trained to do as a Marine, yet neither he nor any of his other comrades were able to prevent the shooting. He realized, too, that his own death would not have resulted in an improved outcome. As a result of these cognitive shifts, the patient was better able to accept both outcomes as unfair “circumstances of war.” The reaction of the patient's senior commanding officer following the death of his comrade was also an important part of processing. The patient felt angry and vulnerable when he saw his commanding officer “break down” outside the hospital.

Several challenges occurred during treatment. For example, during session 1 the patient related a desire to reduce his use of alcohol rather than to abstain from it entirely. Although abstinence may be an ideal goal, the therapist thought the most effective approach would be to meet the patient “where he was at” by using a nonconfrontational approach. By session 4, the patient had surpassed his goal and was abstaining from alcohol the majority of each week. Another challenge involved two separate instances during the patient's in vivo exposure assignments (i.e., social activities) where he felt provoked and became physically violent with other men. Anger was discussed as a common symptom of PTSD, and skills for managing anger were reviewed and role-played in session to help prevent future violent episodes.

In the final session, the patient's progress toward accomplishing the treatment goals established during the first session was reviewed, areas for continued focus were discussed, and an emergency plan to help prevent relapse of alcohol use was generated. In session 12, the patient scored in the nonclinical range for PTSD and depression, with a CAPS score of 42, a PTSD Checklist score of 23, and a BDI score of 3, all of which were reliable changes as defined by Jacobson's Reliable Change Index (

6) and based on standard deviations and scale reliabilities reported for veterans with PTSD (

7). Treatment gains were maintained at the 3-month follow-up visit, as evidenced by a CAPS score of 17, a BDI score of 4, and a PTSD Checklist score of 26. The patient reported using alcohol only a few times since the end of treatment; his average number of drinks consumed per day during the 60 days prior to the 3-month follow-up visit was 0.35. At 6-month follow-up, the patient demonstrated continued symptom improvement, with a CAPS score of 4, a BDI score of 3, and a PTSD Checklist score of 23. He reported no alcohol use during the 60 days prior to the 6-month follow-up visit.