While several studies have established the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral and psychodynamic treatments of borderline personality disorder, relatively few have addressed the long-term effects of these treatments. With a few exceptions (

1–

3), the duration of follow-up in these treatment studies has been short (<1 year). Conclusions about effectiveness require information on the sustained effects of treatment. Although dialectical behavior therapy is a multimodal cognitive-behavioral approach that has the largest empirical base of any psychosocial treatment for borderline personality disorder, the follow-up time frames in the five controlled trials evaluating the lasting effects of this treatment were 1 year or less (

4–

8). The available long-term data reveal a mixed picture, with some evidence suggesting that the strength of the treatment effects on some outcomes diminishes by 6 months after discharge (

4,

6,

8).

We report the results of a 2-year naturalistic follow-up study of 180 individuals enrolled in a randomized controlled trial in Toronto between 2003 and 2006. The design, procedures, and treatment outcomes of the original study are described elsewhere (

9). Briefly, patients diagnosed with borderline personality disorder were randomly assigned to receive 1 year of outpatient treatment consisting of either dialectical behavior therapy or general psychiatric management. After discharge, participants in both groups showed significant improvements on a broad range of clinical outcomes, including suicidal and nonsuicidal self-injurious behaviors, health care utilization (emergency department visits, inpatient days, and psychotropic medication use), borderline psychopathology, symptom distress, depression, interpersonal functioning, and anger. There were no differences between the treatment groups in clinical outcomes.

In the present study, we prospectively evaluated whether these effects were sustained 2 years after treatment (i.e., 3 years after random assignment to a treatment group). Consistent with the original study, our primary outcome measures were the frequency and severity of suicidal and nonsuicidal self-injurious behaviors. We also examined health care utilization, symptom distress, anger, depression, interpersonal functioning, overall quality of life, borderline psychopathology, and remission from borderline personality disorder. Finally, given accumulating evidence from long-term follow-up studies of borderline personality disorder that show persistent impairment in social functioning (

10–

12), we also examined overall functioning.

Method

In the original study, 180 adults meeting DSM-IV criteria (

13) for borderline personality disorder were randomly assigned to 1 year of either dialectical behavior therapy (N=90) or general psychiatric management (N=90). Participants were between 18 and 60 years old and had at least two suicidal or nonsuicidal self-injurious episodes in the past 5 years, with at least one occurring in the past 3 months. Exclusion criteria included substance dependence in the preceding 30 days; a diagnosis of psychotic disorder, bipolar I disorder, delirium, dementia, or mental retardation; a medical condition that precluded psychiatric medications; a serious medical condition requiring hospitalization within the coming year; living outside of a 40-mile radius of Toronto; and having plans to leave the province in the next 2 years.

Dialectical behavior therapy was implemented according to the treatment manuals (

14,

15). General psychiatric management was implemented as a comprehensive approach to borderline personality disorder, developed and manualized for this trial, consisting of psychodynamic psychotherapy, case management, and pharmacotherapy (P.S. Links, Y. Bergmans, J. Novick, J. LeGris, unpublished 2009 manuscript). The psychotherapeutic model in this approach emphasized the relational aspects of the disorder and focused on disturbed attachment patterns and the enhancement of emotion regulation in relationships. Case management strategies were integrated into weekly individual sessions. No restrictions were placed on ancillary pharmacotherapy in either condition; in general, pharmacotherapy was based on a symptom-targeted approach but prioritized mood lability, impulsivity, and aggressiveness as presented in APA guidelines (

16).

Therapists in both treatment arms were well experienced in the treatment of borderline personality disorder, were trained in their respective approaches, and attended weekly supervision meetings. Treatment fidelity was evaluated using modality-specific adherence scales (

17).

All participants underwent 24 months of naturalistic posttreatment follow-up, regardless of whether they completed treatment. Assessments were conducted 18, 24, 30, and 36 months after random treatment assignment, with the exception of the International Personality Disorder Examination (

18), which was administered only at 24 and 36 months. Assessments were conducted by a board-certified psychiatrist and doctoral-level clinicians who were blinded to treatment group. Interrater reliability was maintained on assessment of borderline personality disorder diagnostic criteria (intraclass correlation coefficients, 0.83–0.92), and treatment history data were collected by an unblinded study coordinator.

Although participants were required to discontinue the study treatment at the end of 1 year, three patients in the general psychiatric management arm received an additional 3, 14, and 24 months, respectively, because of therapist concerns about the risks of discontinuing treatment. To determine whether this protocol violation caused meaningful differences in the results, we conducted outcome analyses with and without the inclusion of these three patients.

The study protocol was approved by each center's research ethics board, and participants provided written informed consent for follow-up before enrolling in the original study. Participants were compensated $10/hour for completing each assessment.

Assessments

The follow-up study included the same measures as the original study. As before, the primary outcome measures were the frequency and severity of suicidal and nonsuicidal self-injurious behaviors, as assessed with the Suicide Attempt Self-Injury Interview (

19). To determine whether any of the participants who failed to complete the 36-month follow-up assessment had died by suicide, we searched the Ontario death registry.

Secondary outcome measures included health care utilization, borderline personality symptom severity, symptom distress, anger, depression, interpersonal functioning, and quality of life. We measured health care utilization using the semistructured Treatment History Interview (M.M. Linehan, H.L. Heard, unpublished 1987 manuscript) to obtain self-reported counts of the number of admissions to and number of days in a psychiatric hospital, emergency department visits, medication use, outpatient psychosocial and psychiatric treatment, and use of community and crisis support services. Other secondary outcome measures included the total score on the Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder (

20); the global score on the Symptom Checklist 90–Revised (SCL-90-R;

21); the expressed anger subscore on the State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory (

22); the total score on the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II;

23); and the total score on the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems (

24). The International Personality Disorder Examination (

18) was used to assess remission; consistent with a major prospective follow-up study (

10), remission was defined as meeting no more than two criteria for borderline personality disorder for 1 year.

Overall functioning was assessed based on the EuroQol-5D (

25) thermometer, a measure of health-related quality of life and overall disability, occupational functioning, and receipt of psychiatric disability benefits. Additionally, we assessed whether participants attained normal functioning in terms of their level of symptom distress severity (i.e., SCL-90-R) at 24 and 36 months.

Statistical Analysis of Change

We conducted analyses on both the intent-to-treat population (N=180) and on the per protocol population, defined as the 167 participants who attended at least eight treatment sessions (dialectical behavior therapy, N=85; general psychiatric management, N=82). All primary and secondary outcomes were reanalyzed without data from the three participants who received study treatment during the follow-up phase to determine whether this altered study results.

Several count measures, such as self-harm behaviors, hospitalization days, and emergency department visits, were nonnormally distributed and therefore analyzed using a negative binomial distribution.

We analyzed outcomes that were nonnormally distributed using a generalized estimating equation model, which accounts for collinearity between repeated measurements (

26). Normally distributed outcomes were analyzed using mixed-effects growth curve models. Using these methods, the statistics are based on full information, since participants with partially missing data were included in the analyses.

We analyzed changes between the treatment and follow-up phases on normally distributed outcomes using a piecewise linear response for rate; negative binomial-distributed outcomes were analyzed using step functions for level of response. We modeled each outcome using an initial intercept, a rate or level of improvement for the treatment phase, and a separate rate or level of change for the follow-up phase; each model included a term within each period for a between-group difference in rate.

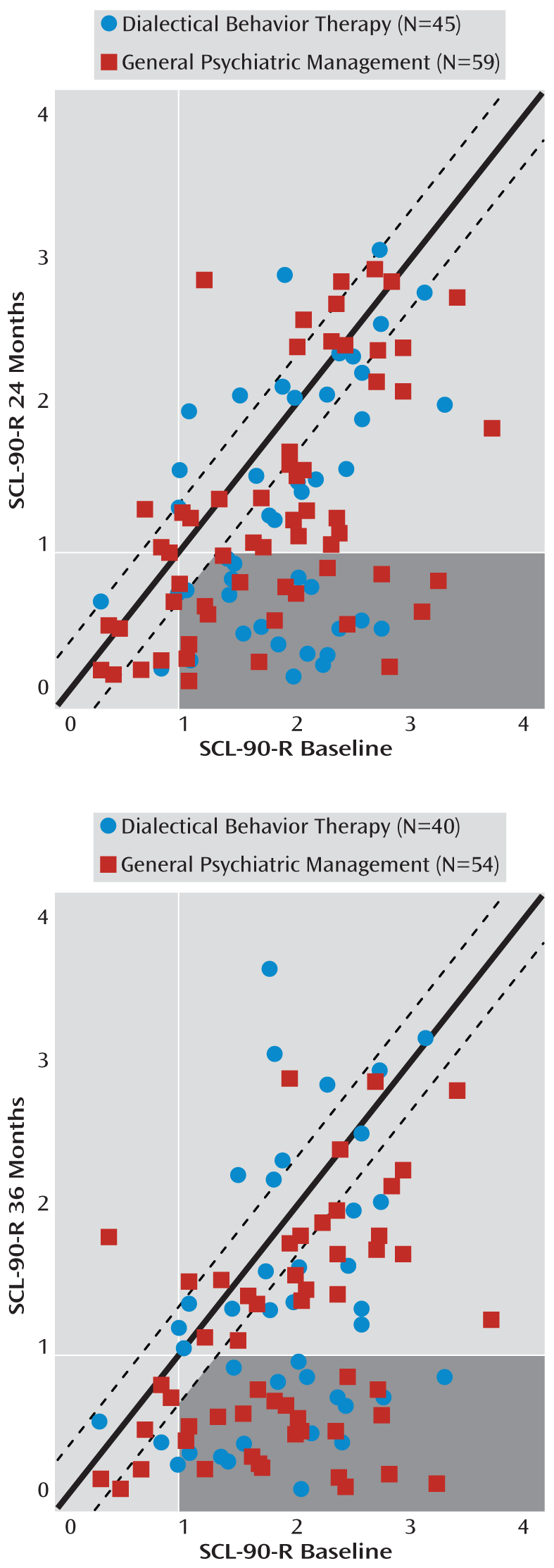

Chi-square tests were used to compare between-group differences in categorical responses (e.g., number of participants meeting borderline personality disorder criteria at endpoints). We used the twofold criterion of Jacobson et al. (

27) to assess clinically significant improvement based on general psychopathology. For these analyses, the SCL-90-R global severity index was selected as the metric because it had been used in two previous trials of dialectical behavior therapy (

3,

28). The criteria for clinically significant change were 1) individual shifts from the dysfunctional to the functional range based on nonclinical population norms (i.e., clinically significant improvement) and 2) a statistically reliable magnitude of change, defined as a difference greater than 1.96 standard errors of measurement estimated from Cronbach's alpha with our baseline data. Participants had to meet both criteria to be classified as achieving clinically significant change. To correct for multiple testing, the Holms-Bonferroni correction was applied, and a threshold of p<0.0015 was considered significant.

Results

Of the 180 participants who entered the original study, 30 (16.7%) failed to attend any follow-up assessments; 131 (73%), 128 (71%), 118 (66%), and 110 (61%) completed assessments at 18, 24, 30, and 36 months, respectively. Completion of all four follow-up assessments was achieved by 87 participants (48%). There were no statistically significant differences between groups in the loss to follow-up (dialectical behavior therapy, N=18/90 [20%] compared with general psychiatric management, N=12/90 [13%]). Overall, participants completed an average of 3.51 out of four assessments (SD=0.89). There were no between-group differences in the number of follow-up assessments attended (dialectical behavior therapy, N=2.53, SD=1.62; general psychiatric management, N=2.88, SD=1.44).

The characteristics of the original 180 participants are described in detail elsewhere (

9). Briefly, they were 30.4 years old on average (SD=9.9) and were mostly women (86.1%); two-thirds (65.0%) were unemployed, and less than half (42.2%) had a college education. With one exception, there were no differences in demographic and diagnostic data, or suicidal and nonsuicidal self-injurious behaviors at baseline between participants who attended one or more follow-up assessments and those lost to follow-up. The prevalence of cluster C personality disorders was higher in those who attended one or more follow-up assessments than those lost to follow-up (44.0% compared with 23.3%, p=0.04).

Treatment Received During Follow-Up

Table 1 presents findings on the utilization of mental health care services during the follow-up phase. The proportion of participants utilizing psychosocial treatments ranged from 51.1% to 62.1% in the dialectical behavior therapy group and from 54.2% to 58.6% in the general psychiatric management group across follow-up assessments. The overall number of psychosocial treatments used by both groups increased significantly from the end of treatment (z=3.28, p=0.001). After correcting for multiple testing, no between-group differences were found (z=1.95, p=0.05).

The proportion of participants who reported any psychiatric hospitalization at each follow-up assessment ranged from 8.5% to 13.8% in the dialectical behavior therapy group and from 10.0% to 15.0% in the general psychiatric management group. The number of posttreatment admissions to psychiatric hospitals remained stable in both groups (z=–0.72, p=0.47), with no between-group differences (z=0.39, p=0.70). The total number of days in psychiatric hospitals remained unchanged from treatment to follow-up for both groups (z=0.49, p=0.63), and there were no between-group differences (z=0.09, p=0.93).

With regard to emergency department visits, the proportions at each follow-up assessment ranged from 24.0% to 43.1% for participants assigned to dialectical behavior therapy and from 27.1% to 36.7% for those assigned to general psychiatric management. The number of emergency department visits over the follow-up phase remained unchanged from treatment level for both groups (z=–1.60, p=0.11), and there were no between-group differences (z=–0.81, p=0.42.).

Participants in both groups showed similar patterns of psychotropic medication use, with the overall proportion for the entire sample across follow-up assessments ranging from 61.9% to 70.3%, compared with 81.0% at baseline. Participants assigned to the dialectical behavior therapy group reported a range from 1.65 to 1.98 psychotropic medications at each follow-up assessment, compared with 1.95 to 2.39 for those assigned to general psychiatric management. During follow-up, no significant differences in the average number of psychotropic medications used compared with the treatment phase were found between participants (z=–0.10, p=0.92). There were no between-group differences in the change in level of psychotropic medications reported (z=–0.18, p=0.86)

Suicidal and Nonsuicidal Self-Injurious Behaviors

Table 2 summarizes the frequency of suicidal and nonsuicidal self-injurious behaviors by group, with statistics based on generalized estimating equations. The effects of both treatments on the frequency and severity of these behaviors persisted after treatment. The proportion of participants reporting suicide attempts at each follow-up assessment ranged from 6.9% to 13.3% in the dialectical behavior therapy group and from 7.4% to 13.2% in the general psychiatric management condition. At 36 months, these proportions were 8.2% and 12.1%, respectively. The reduced rate of suicide attempts observed during the treatment phase was maintained for both groups during follow-up (z=0.47, p=0.64), and this did not differ between groups (z=–0.21, p=0.83). The proportion of participants who reported any nonsuicidal self-injurious behaviors during follow-up ranged from 24.5% to 38.6% in the dialectical behavior therapy condition and from 20.3% to 33.8% in the general psychiatric management condition. The effect of treatment on rates of nonsuicidal self-injurious behaviors was maintained after treatment for both groups (z=–1.82, p=0.07). The medical severity of these behaviors was unchanged from the end of treatment through the follow-up for both groups, indicating that treatment gains were maintained (t=0.78, df=933, p=0.44), and no between-group differences were found (t=1.50, df=933, p=0.14).

No participants died from suicide over the course of follow-up. There were two deaths from natural causes; both of those participants had been assigned to dialectical behavior therapy.

Secondary Clinical Outcomes

Table 3 summarizes secondary clinical outcomes based on mixed-effects linear growth-curve models. After treatment, participants in both groups showed either further improvements or maintenance of treatment effects on all outcomes.

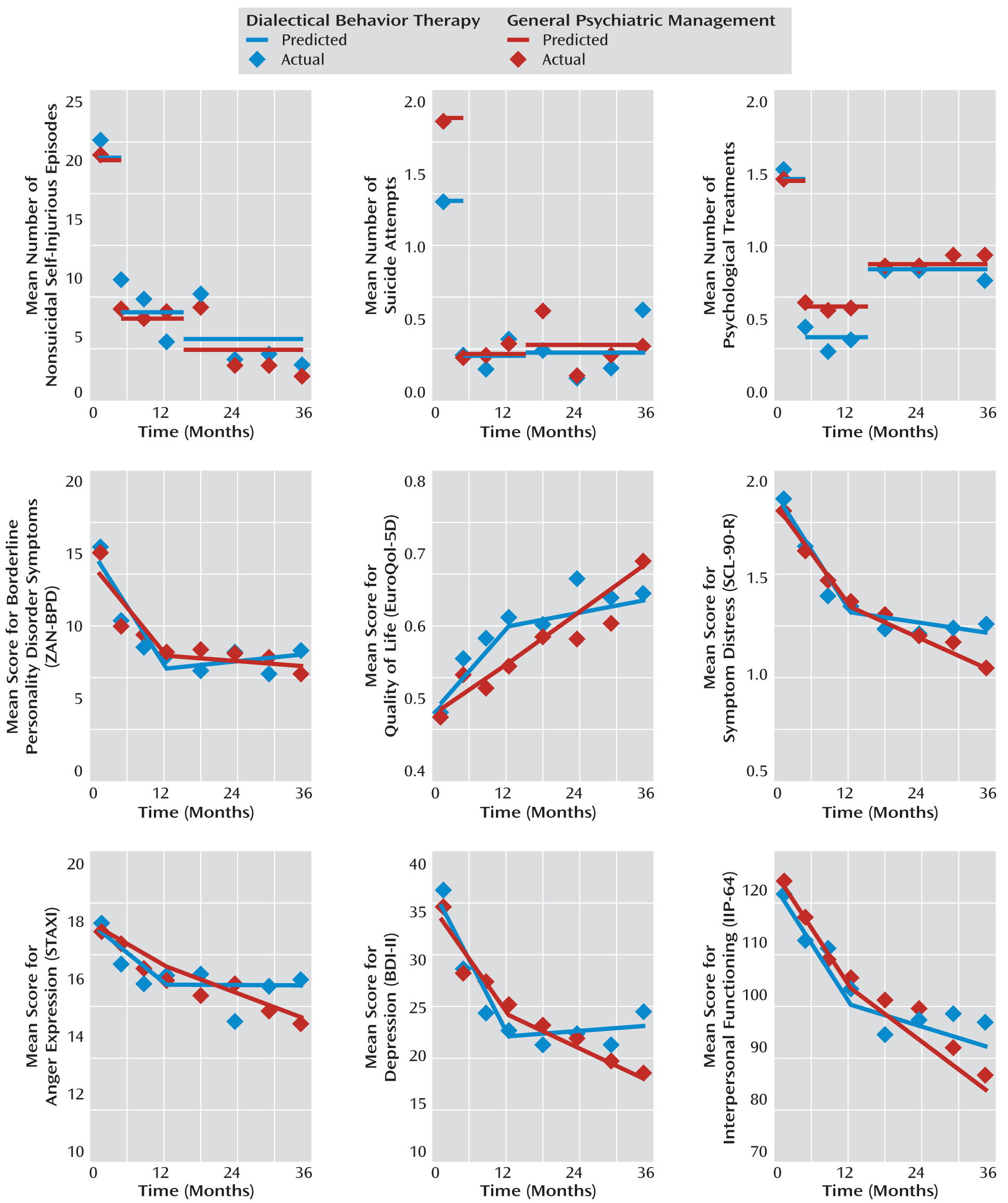

Figure 1 illustrates that the pattern of change from baseline to end of treatment was similar for both groups across a broad range of outcomes. After treatment, both groups showed further improvements in measures of anger, interpersonal functioning, and depression.

On measures of borderline psychopathology, both groups remained unchanged from the end of treatment, indicating that the treatment effects were sustained. Mixed-effects analyses of borderline symptom clusters revealed no differences from 12 to 36 months on affect (t=–0.68, df=923, p=0.50), cognitive (t=–1.10, df=923, p=0.27), impulsivity (t=–0.50, df=923, p=0.95), and interpersonal (t=–1.05, df=921, p=0.29) symptom clusters, and there were no between-group differences. One-year diagnostic remission of borderline personality disorder was achieved in 50% of participants in the dialectical behavior therapy group and in 55% of those in the general psychiatric management group at 24 months, and by 57% and 68%, respectively, at 36 months. There were no between-group differences in diagnostic remission rates after treatment.

On measures of general psychopathology, over the 2-year follow-up both groups maintained the benefits that had been achieved during treatment.

Figure 2 illustrates the number of participants who achieved reliable change and clinically significant change as assessed on the SCL-90-R. Between baseline and 36-month follow-up, 63% of participants in the dialectical behavior therapy group and 70% in the general psychiatric management group achieved clinically reliable change, while 38% and 41%, respectively, fulfilled both criteria and could be considered recovered in a clinically significant way. There were no statistically significant between-group differences.

With regard to health-related quality of life, scores on the EuroQol-5D were in the poor range at baseline, and while both groups showed significant improvements during the follow-up phase (slope=0.29, t=2.17, df=843, p=0.007), their scores remained below normal and in a range comparable to patients with comorbid major depression and anxiety disorders (

29). No significant between-group differences were found (t=–1.72, df=843, p=0.09). Importantly, 51.8% of the sample were neither working nor in school at the end of follow-up, compared with 60.3% at the beginning of treatment. In the dialectical behavior therapy group, 57.9% were working or in school, compared with 40.4% of the general psychiatric management group. No between-group differences were found. Before treatment, 39.7% of the participants had been receiving psychiatric disability benefits (48.2% of those in dialectical behavior therapy and 40.3% of those in general psychiatric management), compared with 38.8% at the end of follow-up. At the end of follow-up, 29.0% of the dialectical behavior therapy group and 46.8% of the general psychiatric management group were supported by psychiatric disability benefits, and there were no between-group differences.

The pattern of results was not altered after removing from the analysis the three participants who received study treatment during the follow-up phase, nor after removing participants who received less than 8 weeks of treatment.

Discussion

Two years after treatment, participants in both groups exhibited sustained benefits of the 1-year intervention. The effects of treatment persisted on all assessed outcomes, including the frequency and severity of suicidal and nonsuicidal self-injurious behaviors, decreased health service utilization, symptom severity, and general psychopathology. Participants also continued to improve during follow-up on measures of interpersonal functioning, anger, depression, and quality of life. However, although quality of life increased after treatment, participants still exhibited considerable functional impairment, as indicated by low rates of full-time employment and continuing high reliance on psychiatric disability benefits.

These findings are noteworthy because they confirm that the effects of both treatments extend beyond initial symptom relief and are associated with long-lasting changes across a broad range of outcomes. The findings from this trial add to a growing number of studies (

1,

2,

7,

30) demonstrating the sustained benefits of specific forms of manualized psychotherapies delivered by trained clinicians working within a team. The effects of treatment did not diminish over time for either group, suggesting that participants continued to derive benefits from what they had gained in treatment. Over time, participants became less depressed, had less anger, and had better interpersonal functioning, which we speculate was because of the treatments' shared focus on enhancing patients' emotion regulation capacities.

The overall rate of diagnostic remission 2 years after treatment (62%) was higher than the rate attained over a comparable time frame (42%) in another prospective follow-up study of borderline personality disorder (

10). Disorder-specific treatments likely hastened recovery, underscoring the value of such treatments.

No differences between treatment conditions were found on any outcomes in our study. In contrast to previous studies comparing specific psychotherapy to nonspecific forms, we compared two manualized psychotherapeutic approaches that were specifically developed for borderline personality disorder and delivered by clinicians with expertise. Considering the field of psychotherapy outcome research more broadly, our findings are consistent with evidence that the number of true differences between psychotherapies developed for specific disorders is zero. Future research needs to be directed toward understanding the effective mechanisms of these two treatments. One possible explanation for the absence of differences between the treatments is that there are common factors that account for the effectiveness of both. We speculate that one common active ingredient is the inclusion of protocols designed to de-escalate suicide crises.

The high rate of unemployment (52%) and reliance on disability benefits (39%) among our participants at the 36-month follow-up is consistent with other follow-up studies (

10–

12), which indicates that poor psychosocial functioning persists even after symptomatic problems diminish. While the dialectical behavior therapy group had more participants who were employed and not on disability at 36 months, between-group differences were not statistically significant, suggesting insufficient power. Future research should be powered to test improvements in functioning, to examine barriers to engaging in productive functioning, such as financial disincentive of reemployment or stigma, and to test therapies designed to improve functioning in patients with borderline personality disorder.

Strengths of this study include the fact that it is the largest treatment follow-up study for borderline personality disorder, the design is prospective, and the sample is well characterized. The follow-up time frame is reasonably longer than those used in other studies of dialectical behavior therapy, and the follow-up rates were good, with 83% of participants attending at least 1 assessment and providing complete data on 3.5 of four assessments. In addition, the assessments were based on face-to-face interviews, the assessors were blind to treatment assignment, and the outcomes were diverse and broad and were assessed with standardized measures.

One limitation of our study is that data were not available for every participant at each assessment. However, because our sample was relatively large, the study remained adequately powered to detect differences even with missing data. Furthermore, the statistical methods used to analyze outcomes are based on all available data from all participants. Another limitation is that it is possible that the participants who were lost to follow-up were doing poorly, and the loss of their data may have biased the outcomes in a positive direction. It should also be noted that since this was a naturalistic study, access to treatments (with the exception of the study treatments) was uncontrolled. Additionally, self-report of treatment history and suicidal behavior may be subject to response biases. Approximately half of all participants reported receiving treatment during the follow-up phase, and this may have affected outcomes. Finally, in the absence of a control group undergoing no treatment, the natural course of the disorder is not known.

There are several directions for future research. For example, modeling individual trajectories can help to detect different patterns of treatment response. Additionally, given the lack of availability of effective treatments for borderline personality disorder, research is needed on the effectiveness of less-intensive models of care in order to help inform decisions about the allocation of scarce health care resources.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Susan Wnuk, Joshua Murray, and numerous research analysts, volunteers, and colleagues at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, St. Michael's Hospital, and the University of Toronto Department of Psychiatry.