T

o the Editor: Conversion disorder, formerly known as hysteria, is thought to symptomatically manifest in the sensory-motor domains as a result of emotional distress (

1). The prevailing neurocircuitry models based on functional MRI (fMRI) studies of patients with conversion paralysis support this view by suggesting an association of frontolimbic hyperfunction and suppressed motor responses (

2). Less is known, however, about the neural signature of visual conversion disorder. While two recent fMRI studies have documented altered, but not absent, visual cortex responses in patients with conversion blindness (

3,

4), it remains unclear whether the neural processing of symptom-related cues is preserved.

We report here on a 25-year-old man who fulfilled DSM-IV criteria for visual conversion disorder after experiencing recurrent brief episodes of medically unexplained complete bilateral visual loss. These episodes had occurred since he was 17 years old when his close boyhood friend accidentally died from autoerotic asphyxiation. The current episode was preceded by overwhelming feelings of guilt and visual pseudo-hallucinations showing his deceased friend’s face grimacing with agony. In an attempt to elucidate the underlying neurocircuitry using fMRI, we scanned the patient during the episode of conversion blindness and after spontaneous remission 5 days later, thus enabling intra-individual comparison of neural activity during symptomatic and asymptomatic states in the absence of pharmacotherapy.

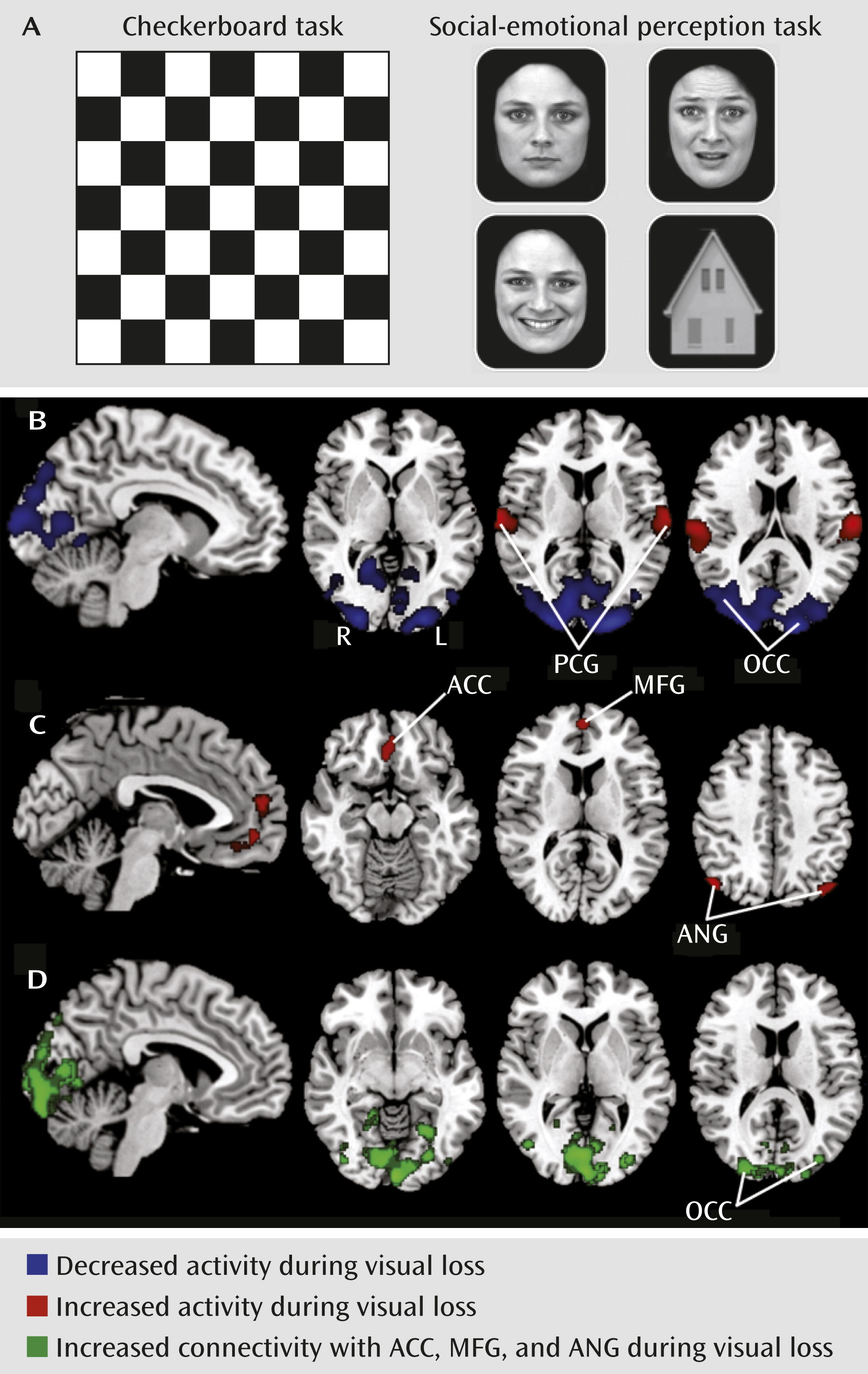

Our fMRI data analysis confirmed the presence of unaltered basic visual cortex responses to checkerboard stimulation (

Figure 1A) during conversion blindness (

3,

4). In contrast, analysis of higher-order visual responses to complex stimuli (a social-emotional perception task) revealed hypofunction in the occipital cortex and hyperfunction in the postcentral gyrus bilaterally and the right superior temporal gyrus (

Figure 1B). The extraction of emotion-specific activity yielded increased responses in the angular gyrus bilaterally, the left medial frontal gyrus, and the left anterior cingulate cortex—regions implicated in a variety of brain functions including emotional regulation and moral reasoning (

Figure 1C). A psychophysiological-interactions analysis revealed enhanced functional coupling of this network with down-regulated visual areas (

Figure 1D).

Taken together, our findings may help extend current neurocircuitry models of visual conversion disorder by proposing a symptom-related functional association of overactivity in fronto-parietal regions and suppressed responses in interconnected visual areas.