On August 24, 2011, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a drug safety “MedWatch” communication regarding abnormal heart rhythms associated with high dosages of citalopram hydrobromide (

1). This FDA warning informed health care professionals that citalopram should no longer be prescribed at dosages above 40 mg/day because of potential abnormal changes in electrical activity of the heart. The warning indicated that the citalopram drug label had previously stated that certain patients may require dosages of up to 60 mg/day, yet studies had not shown benefits for dosages above 40 mg/day. The drug label was subsequently revised to include information regarding potential negative cardiac outcomes, specifically QT interval prolongation (also known as long QT syndrome) (

2) and torsade de pointes, which can be fatal. The warning recommended avoiding higher dosages, specifically among patients with congenital long QT syndrome, congestive heart failure, bradyarrhythmias, or predisposition to hypokalemia or hypomagnesemia. Concerns about risks of citalopram use were revised and further elucidated by the FDA on March 27, 2012 (

3). The updated FDA warning recommended that dosages >20 mg/day should not be used in adults over age 60.

The stated bases for the warning were twofold: 1) postmarketing reports of long QT syndrome and torsade de pointes associated with citalopram and 2) the FDA’s analysis of an unpublished study assessing the effects of 20-mg and 60-mg daily doses of citalopram on QT intervals in adults. According to the description provided in the warning, the study was a multicenter double-blind placebo-controlled crossover study with 119 subjects. Compared with placebo, corrected QT (QTc) intervals were 8.5 ms and 18.5 ms for 20 mg/day and 60 mg/day of citalopram, respectively. QTc intervals for 40 mg/day of citalopram were estimated to be 12.6 ms.

While this FDA warning provided data regarding adverse electrophysiologic changes observed in patients receiving citalopram in a single study, risks of negative patient-centered health outcomes, including ventricular arrhythmia and mortality, have not been systematically assessed to fully ascertain population risks. This is critical to do because citalopram has been well tolerated by many patients over a long time, is available in a low-cost generic formulation, and is an antidepressant of choice on many prescription formularies. All of these issues imply that the warning could have substantial implications, particularly for integrated health care delivery systems, such as the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), where citalopram is one of four selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) on the formulary (

4). Therefore, we sought to evaluate potential dose-dependent risks associated with citalopram use in the VHA. We identified all depressed VHA patients who received a prescription for citalopram since its generic form became available in 2004. We examined relationships between citalopram and both ventricular arrhythmia and death, and we conducted all study analyses using a comparison medication, sertraline, which was not subject to the FDA warning.

Results

Of 618,450 individuals who received a prescription for citalopram between 2004 and 2009, 6,754 (1.1%) experienced ventricular arrhythmia. Of 64,970 (10.5% of the total) patient deaths that occurred during the study, 20,509 (3.3%) were from cardiac causes. Of 365,898 individuals who received a prescription for sertraline, 4,198 (1.1%) experienced ventricular arrhythmia. Of 45,768 (12.5% of the total) patient deaths, 14,808 (4.0%) were from cardiac causes.

Clinical and demographic characteristics of the study patients are summarized in

Table 1. Similar to the overall VHA patient population, those included were primarily white (72.5%), non-Hispanic (84.0%), and male (90.4%), with a mean age of 56.9 years (SD=15.2). Patients receiving medications associated with risk of torsade de pointes comprised 36.1% of the sample.

Unadjusted rates of outcomes by daily dose are presented in

Table 2. Rates of each outcome decreased with higher doses; for citalopram, 18.6% of patients received dosages >40 mg/day (comprising 6.9% of total person-time). Of the total ventricular arrhythmia cases, 44.6% occurred when the prescribed dosage of citalopram was 1–40 mg/day, and 6.1% occurred at dosages >40 mg/day. Of all deaths from any cause, 29.6% occurred when the dosage was 1–40 mg/day, and 3.9% occurred at dosages >40 mg/day. Of all deaths from cardiac causes, 31.6% occurred when the dosage was 1–40 mg/day, and 4.1% occurred at dosages >40 mg/day. Of all deaths from noncardiac causes, 28.7% occurred when the dosage was 1–40 mg/day, and 3.8% occurred at dosages >40 mg/day. For sertraline, 35.9% of patients received dosages >100 mg/day; 35.8% of ventricular arrhythmia cases occurred when the dosage was 1–100 mg/day, and 14.5% occurred at dosages >100 mg/day. Of all deaths from any cause, 25.0% occurred when the dosage was 1–100 mg/day, and 8.9% occurred at dosages >100 mg/day. Of all deaths from cardiac causes, 27.2% occurred when the dosage was 1–100 mg/day, and 9.4% occurred at dosages >100 mg/day. Of all deaths from noncardiac causes, 23.9% occurred when the dosage was 1–100 mg/day, and 8.7% occurred at dosages >100 mg/day.

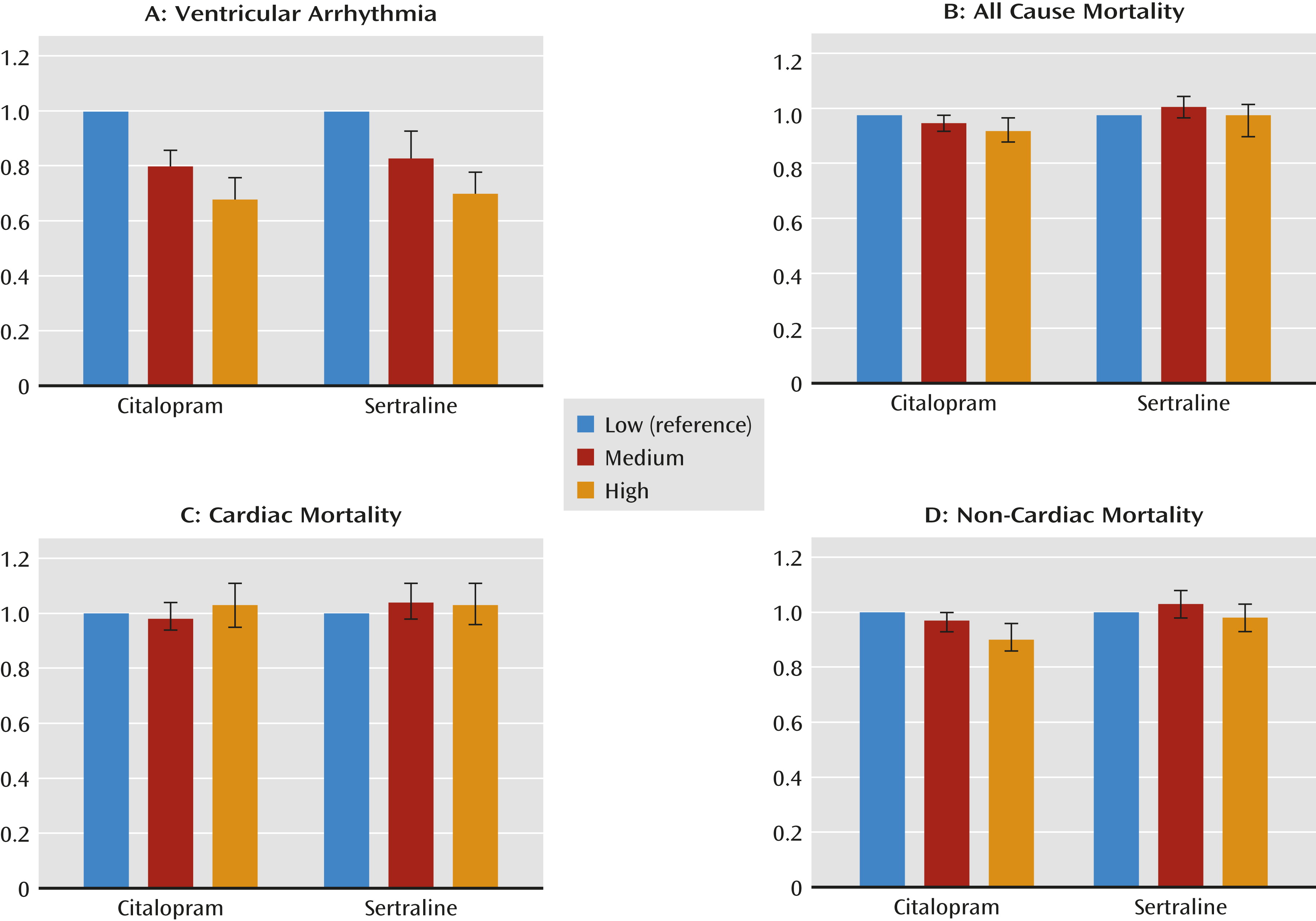

Findings from the adjusted Cox models, controlling for covariates, for each outcome variable are reported in

Tables 3 and

4 and in

Figure 1. Citalopram daily doses >40 mg were associated with lower risks of ventricular arrhythmia (adjusted hazard ratio=0.68, 95% confidence interval [CI]=0.61–0.76), all-cause mortality (adjusted hazard ratio=0.94, 95% CI=0.90–0.99), and noncardiac mortality (adjusted hazard ratio=0.90, 95% CI=0.86–0.96) compared with daily doses of 1–20 mg; no elevation in risks of cardiac mortality were found. Daily doses of 21–40 mg were associated with lower risks of ventricular arrhythmia (adjusted hazard ratio=0.80, 95% CI=0.74–0.86) compared with doses of 1–20 mg/day but did not have significantly different risks of any cause of mortality. The sertraline analyses resulted in similar findings, except there were no significant associations with all-cause mortality or noncardiac mortality.

Sensitivity Analyses

To address the potential concern that VHA patients experiencing ventricular arrhythmias were treated outside the VHA system, we examined ventricular arrhythmia outcomes for patients with non-VHA utilization (i.e., the random samples from data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services). In these samples of approximately one-quarter of patients from both the citalopram and sertraline cohorts, we found results similar to those in our primary analyses: higher daily doses of citalopram and sertraline were associated with lower risks of ventricular arrhythmia (>40 mg/day of citalopram, hazard ratio=0.77, 95% CI=0.67–0.89; >100 mg/day of sertraline, hazard ratio=0.68, 95% CI=0.59–0.78).

Discussion

This study provides evidence on outcomes associated with citalopram (and sertraline) use in the largest samples, to our knowledge, ever analyzed. Unlike previous studies, we evaluated long-term risks and outcomes by daily dose across a large patient population, controlling for sociodemographic characteristics and clinical features implicated in negative events associated with citalopram use. We also used a comparison medication not subject to the FDA warning. Time-varying measurement that captured changes in dosing as they occurred indicated no elevation in risks of ventricular arrhythmia, nor of all-cause, cardiac, and noncardiac mortality, from higher dosages of either medication. Higher dosages of citalopram and sertraline were associated with significantly lower risks of ventricular arrhythmia. Furthermore, citalopram dosages >40 mg/day were associated with lower risks of all-cause and noncardiac mortality, yet there were no significantly lower risks in the sertraline cohort. These findings raise questions regarding the continued merit of the FDA warning and provide support for the question of whether the warning itself will cause more harm than good (

18).

These findings add to another recent pharmacoepidemiology study that did not find evidence that citalopram is associated with elevations in the risks of QTc prolongation and torsade de pointes (

19). The link between citalopram and torsade de pointes is primarily derived from case reports (

20). Citalopram was the third most common suspected drug (9% of cases) out of 27 different medications in an assessment of simultaneous torsade de pointes cases between 1991 and 2006 in Sweden (

21). Case reports of overdose have described adverse cardiac outcomes associated with citalopram and torsade de pointes in an elderly man with multiple medical problems (

22,

23). Conversely, several existing national and international studies found essentially benign outcomes associated with citalopram use. A meta-analysis published in 1999 examining 40 prospective and retrospective studies conducted between 1978 and 1996 (including almost 2,000 patients and more than 6,000 ECGs) found that there were no significant effects of citalopram on cardiac conduction during short- or long-term treatment among adults (including older adults) (

24). Another study that reviewed 10 years of data from 30 randomized clinical trials in European and American patients found that citalopram was well tolerated in the therapeutic dosage range (20–60 mg/day) (

25).

Citalopram was approved by the FDA in 1998 (

26), and its patent expired in 2004. By 1999, it had been used by more than 8 million people in 60 countries (

27). However, previous experience with other medications indicates that awareness of serious adverse events may come only after many years of use, with a probability of 20% that a drug will acquire a “black box” warning or be withdrawn from the market within 20 years (

28). Furthermore, prolonged QT intervals have been the single most common cause of a drug being withdrawn or restricted in the past decade (

29). The warning regarding citalopram dosing arose after many years of use by a large number of patients without widespread reports of serious adverse events. Yet postmarketing FDA warnings in general, and for this specific adverse outcome, are neither new nor rare.

FDA warnings have historically changed provider and patient behavior, with intended and unintended effects (

30). After the 2003 FDA advisory regarding potential suicidality among children receiving SSRIs for depression, rates of antidepressant use decreased among both children and adults, and there were no compensatory increases in psychotherapy or use of other psychotropic medications (

30). It is likely that some inappropriate use of these medications decreased, but it is also likely that a substantial portion of appropriate use decreased as well. The FDA warning has already begun to limit citalopram prescribing practices (

18), even though some high-risk patients may benefit from higher dosages of citalopram (

31).

Several investigators have questioned the thoroughness of the “thorough QTc study” cited in the FDA warning (

20,

31) and the warning more broadly (

18). There are limited data available to assess risks of these outcomes among patients receiving approved citalopram dosages (as opposed to overdoses) (

32,

33). There are questions regarding the clinical significance of the findings in the unpublished FDA data (

31). The FDA recently responded to criticism of the citalopram warnings in a letter to the editor (

34). The FDA maintained that the warning was based on worrisome increases in QTc intervals and that there was no evidence of patients responding better to dosages of 40 mg/day than to doses of 60 mg/day. Yet the FDA acknowledged that the relationship between the magnitude of QT prolongation and torsade de pointes is unknown and that there are no data available demonstrating the benefit or harm of dosages of 40 mg/day compared with 60 mg/day (

34).

Our results, taken together with the FDA warning, raise a number of questions regarding the prescribing of citalopram. Should patients treated with more than 40 mg/day of citalopram have their dosage reduced? Should dosage be modified for those with the risk factors outlined in the warning? Should health care providers alter how they prescribe citalopram for new users? Should providers order ECGs for patients thought to be at potential risk of negative cardiac outcomes before writing new prescriptions or for those currently taking citalopram at high dosages, or any dosage? Should patients be switched to other antidepressants that may have similar risk profiles but are not subject to specific FDA warnings? Additional research and other data sources may be needed to examine and validate potential mechanisms of the link between citalopram and cardiac mortality to provide further guidance to clinicians.

While we conducted the largest study to date regarding the relationship between citalopram dosing and negative health outcomes, there were factors that we did not examine. Although we could not determine whether more patients with treatment-resistant depression received higher dosages, we found that both older patients and patients with higher comorbidity levels received lower dosages of both citalopram and sertraline. This may mean that there could have been residual confounding by comorbidity; patients with more physical health problems were less likely to receive high dosages but were more likely to die, and the degree of physical health problems may not have been fully captured by the selected control variables. This could potentially explain the appearance of a protective mortality effect of higher dosages. However, the results indicate that even if this were the case and there was a relationship between citalopram use and adverse cardiac outcomes that could not be detected with these data, patient selection and prescribing practices prior to the FDA warning appear to have offset this issue. Furthermore, while physicians may have been cautious before the FDA warning was issued, they also prescribed lower dosages of sertraline for older patients and patients with more comorbidities.

We did not examine patients without a depression diagnosis who received prescriptions of citalopram for off-label purposes, that is, for indications other than depression (e.g., to relieve pain from diabetic neuropathy, for headache syndromes, or for premenstrual dysphoric disorder) (

35). We did not measure guideline-concordant antidepressant treatment, degree of adverse event monitoring, or use of other psychiatric or medical services that may moderate the relationship between antidepressant use and outcomes (

36). We examined medication use as prescribed, but as with all pharmacoepidemiology studies, we are unable to verify actual ingestion of medication. We focused on daily dose prescribed (the focus of the warning) rather than cumulative exposure; long-term use of higher dosages may potentiate higher risks. Cardiac outcomes may be misclassified, and administrative data may underreport actual events. National Death Index data may misreport causes of death, although it is the gold standard for documenting mortality (

7). While we found lower risks of noncardiac and all-cause mortality associated with higher dosages of citalopram (and not sertraline), we cannot determine whether curtailing the use of citalopram would increase the risk of mortality. Finally, while we studied a patient population that may not be generalizable to other adult populations of depressed patients, it is uncertain how the effect of medication dosage would vary based on demographic characteristics or site of care. In fact, a strength of VHA data is that the patient population largely comprises men and older adults with higher risks of negative cardiac outcomes (

37). Although it is unclear how these limitations might influence our findings, the fact that our results were so similar for both the citalopram and sertraline cohorts bolsters our confidence that these findings were not unique to patients receiving citalopram. However, we do not make any claims regarding citalopram’s safety; all medications have some risks, and we did not include a nondrug comparison group. Rather, we have documented the lack of negative outcomes associated with daily doses >40 mg, or even >20 mg (which was the focus of the March 2012 FDA warning regarding adults over age 60), compared with lower doses.