Studies of predictors of outcome in late-life depression are limited. Some studies found no predictors (

11–

13). A few predictors have been suggested in individual studies. Advanced age, for example, was predictive of poorer outcome in four studies (

14–

17). One prospective placebo-controlled study of patients age 75 and older with major depression found no significant advantage for citalopram in that age group (

18). A greater medical burden has been associated with poor outcome in open-label studies (

19–

21), although placebo-controlled studies have not found a decrement in the acute-phase drug effect (

22,

23). One study found greater medical burden to be associated with higher recurrence rates during maintenance treatment (

24). These findings emphasize the important distinction between predictors of global outcome and moderators of drug effects specifically (drug-placebo differences). Greater baseline depression severity has been found to predict poorer global response (

25), but a substantial literature in mixed-age placebo-controlled trials indicates that greater severity is often associated with larger drug-placebo differences in change scores (

26–

28). Recurrent depression has been reported to be associated with less global improvement (

29,

30), but in mixed-aged studies, recurrent depression has been reported to have larger drug-placebo differences in response rates (

31,

32). Flint and Rifat (

33) found that age at onset was not predictive of outcome in elderly patients. Roose et al. (

18) found evidence suggestive of an effect of age at onset on drug-placebo differences, but the number of early-onset patients was small and the effect not significant. In mixed-aged samples, female sex was associated with better global outcome in open-label studies (

34), but male sex was associated with greater drug-placebo differences (

35). Open-label studies of late-life depression have found that anxious depression predicts poorer global outcome (

36,

37), but a trial-level meta-analysis found that anxious depression was not associated with lower drug-placebo differences in older depressed patients (

38).

In this study, we examined possible moderators of antidepressant response in elderly depressed patients participating in randomized placebo-controlled clinical trials. Our objective was to identify variables that moderate clinically meaningful differences in response between antidepressant and placebo. We specifically examined two hypotheses, namely, that advanced age is associated with lower drug-placebo differences and that early age at onset or long duration of illness, recurrent depression, and greater baseline depression severity are each associated with greater drug-placebo differences.

Method

In a previous systematic review (

10), we identified 10 placebo-controlled trials, published or presented by December 2006, of second-generation antidepressants (non-tricyclic antidepressants) marketed in the United States. We required that the trials included patients age 60 or older who had major depressive disorder and were living in the community and that the trials were not restricted to one medical disorder (e.g., poststroke depression). For that study, we searched MEDLINE and the Cochrane clinical trials database, examined references cited, and searched presentations at national meetings to identify the 10 trials. Before conducting the present analysis, we repeated the literature search through December 2010. Four trials that were initially presented as posters had since been published, but we found no new trials meeting our criteria.

Based on this literature review, we selected factors that have been associated with either antidepressant response or antidepressant-placebo differences and that are commonly documented in clinical trials. The factors were age, age at illness onset, sex, course of illness (single episode or recurrent depression), baseline depression severity, and cognitive impairment. We elected to examine the duration of illness computed as current age minus age at onset, rather than as a threshold age at onset, because it was more informative in older patients. These factors were examined to determine whether they moderated differences between drug and placebo response. Medical burden was not included because it was not documented in a uniform or quantified manner in the studies we examined.

In our previous meta-analysis of antidepressant efficacy (

10), we examined published trial-level outcome data. In the present study, we used individual patient data for the variables of interest, as well as treatment assignment and outcomes on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) (

45) and the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) (

46).

Statistical Analysis

Response to treatment was defined as a change ≥50% from baseline in HAM-D or MADRS score. Baseline depression severity was defined using the 17-item HAM-D score. Scores from one trial using the 24-item HAM-D were converted to 17-item HAM-D scores using a proportional estimate based on maximal possible scores in nonpsychotic patients. To convert MADRS scores to 17-item HAM-D scores in one trial, we used a factor derived from a late-life major depression study that used both scales (

47). Analyses were performed on data from the intent-to-treat samples.

We first performed univariate analyses to determine the association of each variable with response and with the treatment group-response interaction while controlling for study. The interaction term in the model tests whether the difference in response between the placebo and active drug groups differs as a function of the covariate. For example, is the difference in response between placebo and active drug groups the same for males and females? To facilitate comparisons among the variables, we limited analyses to the trials that collected data for all the variables. Age, illness severity, and illness duration were converted to categorical variables, which normalized their distribution and facilitated inspection of response rates by category. Measures of age and depression severity according to the HAM-D were divided into quartiles (age categories were 60–65, 66–69, 70–75, and 76–98 years; HAM-D score categories were <19, 19–20, 21–23, and >23). Because about one-third of the patients had a short duration of illness (<2 years), this measure was divided into tertiles (<2, 2–10, >10 years). Linearity of the relationship of response with drug or placebo was assessed with Jonckheere-Terpstra tests (

48). Effect sizes of the difference in response rates for variable categories were calculated as follows: (2×arcsin [square root of drug response rate]) – (2×arcsin [square root of placebo response rate]) (

49). Variables were also entered in a regression model using maximum likelihood estimation using the PROC LOGISTIC procedure in SAS, version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.) to estimate their association with response and with the treatment group-response interaction. In two trials with an active comparator, we collapsed the two active arms in those studies into a single active treatment group. In one trial comparing two formulations of the same medication and one trial comparing two dosages of a medication, we combined the drug groups within the trial.

Potential covariates (sample size, number of sites, number of treatment arms, year of publication, trial duration, drug tested, and dropout rates) were examined, as was an unordered categorical variable indicating the study in which the participant was enrolled. Several covariates, such as the sample size, were collinear with the study variable. Other covariates were examined for their association with outcome, but none was significantly associated with the treatment group-response interaction. As a consequence study alone was entered as a covariate in the regressions.

Results

Individual patient data for the variables of interest were obtained from the sponsors of all 10 trials identified in the search (

18,

47,

50–

57). Information on age, sex, and baseline depression severity was collected and documented in all trials (

Table 1). Course of illness was documented in eight trials, and age at onset in seven. Data for all of the moderator variables were available in seven of the trials (N=2,283), and the data from these trials were used in our analyses. The characteristics of the seven trials are summarized in

Table 2. Trial duration varied from 8 to 12 weeks. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors were examined in five trials, and duloxetine and bupropion were examined in one trial each. The seven trials included a total of 2,488 patients (1,607 women and 881 men), of whom 1,494 received active drug and 994 received placebo. All trials were sponsored by the manufacturer of the antidepressant and had Jadad scores of 4 or 5, indicating that the trials were of good to excellent methodological quality (

58).

We requested information regarding cognitive status on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (

59), which was used in all studies; however, several trials documented only whether or not the MMSE threshold was met rather than the score. Four trials included patients with MMSE scores below 24, but in none of those trials were there more than 10 patients in that category. Hence, we did not assess the influence of MMSE score on outcome.

Response to Treatment

Response rates to active drug and placebo were examined using individual patient data while controlling for study. Overall, active drug treatment was more effective than placebo (response rates were 48.7% and 40.0%, respectively; χ2=17.30, df=1, p<0.0001).

Moderators of Response

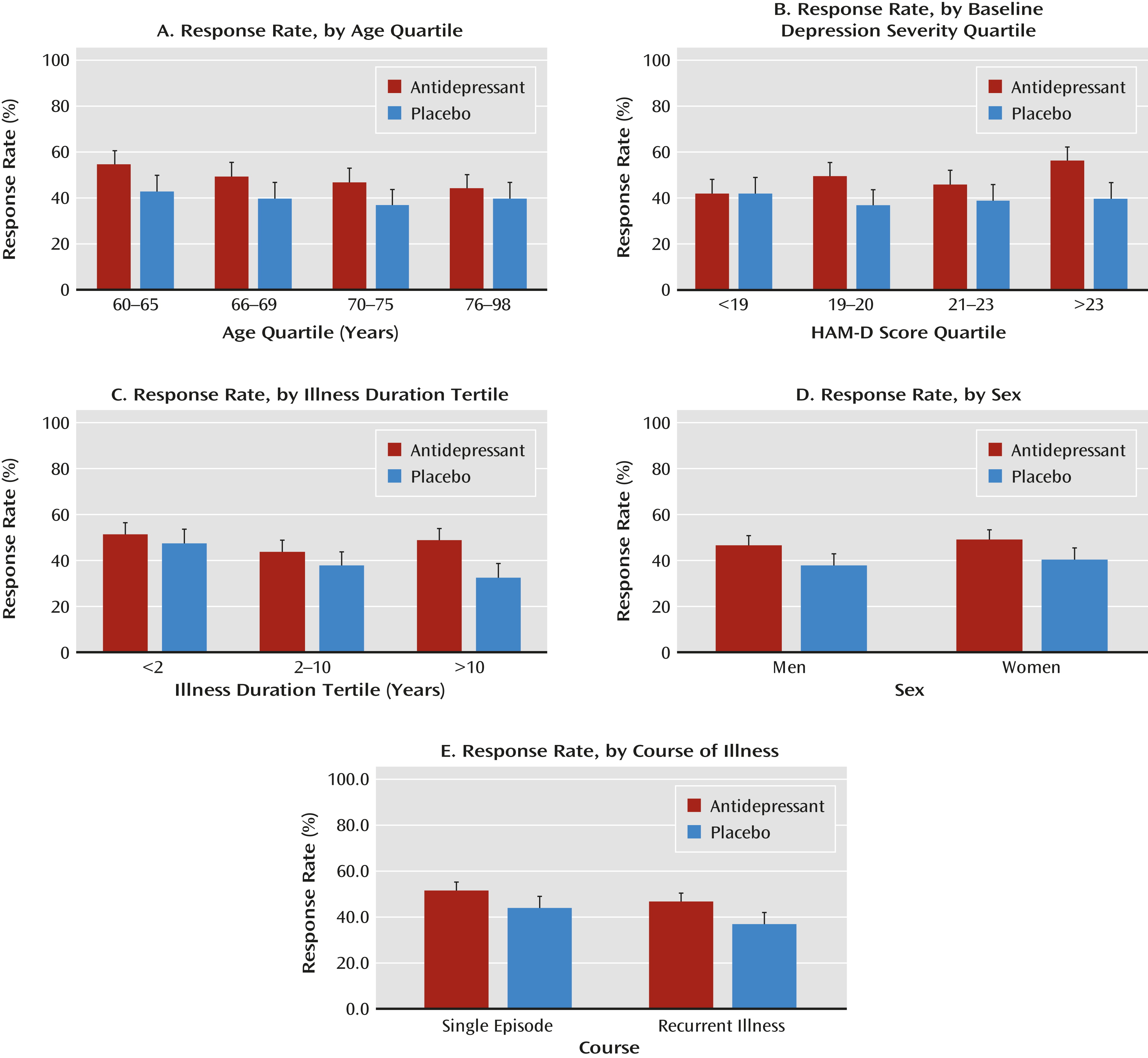

Response rates by category for the five variables are summarized in

Figure 1. Univariate analyses of the association of the variables with the treatment group-response interaction indicated that duration of illness (Wald χ

2=7.74, df=2, p=0.02) and baseline depression severity (Wald χ

2=7.96, df=3, p=0.047) were significantly associated with drug-placebo differences. Significant linearity was demonstrated for the relationship of duration of illness and response rates in the placebo group (z=−3.81, p=0.0001) but not with response rate in the drug group. Baseline depression severity was associated with response rate in the drug group (z=3.40, p=0.0007) but not in the placebo group. Course of illness (single episode or recurrent depression), sex, and age were not significantly related to the treatment group-response interaction.

In the multivariate logistic regression, only duration of illness was associated with the interaction of treatment group and response, that is, associated with the drug-placebo difference (

Table 3). We also performed a multivariate regression using the endpoint HAM-D score (last observation carried forward) as a continuous dependent variable and entering the baseline score as a covariate. Duration of illness remained significantly associated with the treatment group-response interaction (F=4.03, df=2, 2255, p=0.02). Age, sex, and course were not significantly associated. The strength of the association of depression severity with the treatment group-response interaction was essentially the same as that using response as the outcome (F=2.62, df=3, 2255, p=0.049).

Duration of Illness and Drug-Placebo Differences

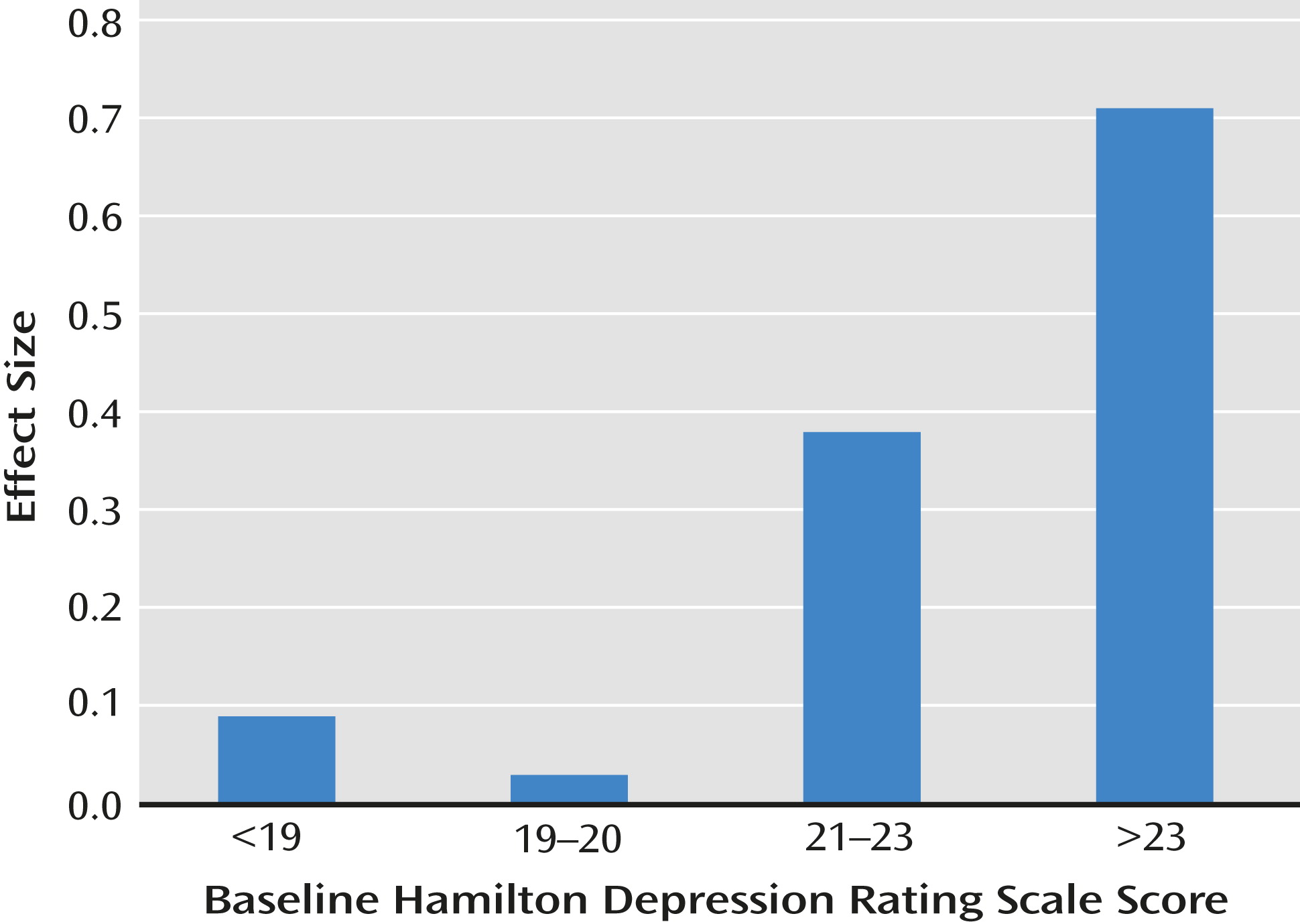

Drug-placebo differences were greatest in the tertile with illness duration >10 years. Among patients with an illness duration >10 years, a logistic regression entering age, sex, illness course, and baseline depression severity and controlling for study demonstrated that severity was also associated with the treatment group-response interaction (the drug-placebo difference) (Wald χ

2=8.54, df=3, p=0.04). The interaction of duration of illness and depression severity with the effect size of the drug-placebo difference is illustrated in

Figure 2. In the 385 patients with a long duration of illness (>10 years) and moderate to severe depression (HAM-D score ≥21), response rates were 58.0% and 31.4% in the drug and placebo groups, respectively (the effect size for the drug-placebo difference was 0.54), but in the remaining patients, the effect size was small (effect size=0.09).

Discussion

Our findings suggest that the duration of depressive illness moderates antidepressant response in patients over age 60. Patients with an illness duration >10 years showed greater drug-placebo differences, while those with a short illness duration showed no drug effect. In patients with a duration of illness >10 years, baseline depression severity contributed to drug-placebo differences. Illness duration and severity identify a subgroup of patients with clinically meaningful drug-placebo differences, resulting in a number-needed-to-treat of 4. Yet, only 385 of the 2,235 late-life depression patients in these seven clinical trials had a long duration of illness and at least moderate depression severity. It is unclear whether the proportion of patients with long-duration depression in these clinical trials is similar to that among patients in the community. Age, sex, and course of illness (single episode or recurrent depression) did not moderate response in this sample.

Our findings are similar to those of previous studies examining relationships of illness course and severity to treatment response in nongeriatric samples. Two antidepressant trials of depression patients with cardiac disease (the Sertraline Antidepressant Heart Attack Trial [SADHART] [

31] and the Canadian Cardiac Randomized Evaluation of Antidepressant and Psychotherapy Efficacy [CREATE] Trial [

32]) found antidepressants more effective than placebo, but post hoc analyses showed that single-episode patients had a high rate of response to placebo with no incremental advantage for active drug. Although these were both mixed-aged samples and used single-episode versus recurrent course to examine differences in response to drug and placebo, both samples were relatively older (mean ages, 57 years and 58 years), and single episodes are likely to be associated with a shorter duration of illness than recurrent episodes. In both of those studies, drug treatment did show an advantage in patients with recurrent depression. With respect to depression severity, two meta-analyses of mixed-age samples found that the effect size of mean score drug-placebo differences increased with severity (

27,

28). The SADHART study also noted that active drug was not more effective than placebo in patients with a HAM-D score <20.

In the present study, antidepressants offered no advantage over placebo in patients with a short duration of illness (<2 years), that is, late-onset depression. The response rate to placebo in this group was 47.7%, significantly higher than in those with a long duration of illness (32.8%). This pattern of placebo response appears similar to that observed in the CREATE and SADHART trials in single-episode and recurrent-episode patients with depression. The late-life depression trials were not designed to examine what factors mediate placebo response, but these data suggest either that patients with late-onset depression are more likely to remit spontaneously or that they are responsive to the nonspecific supportive elements associated with frequent visits in clinical trials.

The greater benefits of antidepressants in patients with a long duration of illness may be consistent with models of depression emphasizing kindling with repeated episodes of depression (

60). Perhaps the neuroprotective effects of antidepressants are more important in such patients (

61).

Our findings do not indicate what explains the lack of drug effects (drug-placebo differences) in late-onset depression. Historically, late-onset depression has been associated with degenerative brain disease, which may reduce antidepressant effectiveness. Studies reviewed previously (

39–

44) found that depressed patients with executive dysfunction or Alzheimer’s dementia are less responsive to antidepressants. However, in the placebo-controlled trials of antidepressants in depressed patients with Alzheimer’s disease, only two of the nine trials studied limited patient selection to moderately severe depression (mean HAM-D score >20 or equivalent MADRS score) (

62,

63), and in the two largest trials (

40,

64), about three-quarters of the patients had late-onset depression (P. Rosenberg and S. Banerjee, personal communication, 2011). The effectiveness of antidepressants in Alzheimer’s patients who are similar to the drug-responsive subgroup identified in this report (those with a long illness duration and at least moderate depression severity) has not been explored.

While patients with late-life depression and a short duration of illness did not show a clinically meaningful drug effect during acute-phase treatment, our findings do not indicate that antidepressant treatment is of no value in this group. About half of these patients failed to respond to either drug or placebo, and further treatment may be useful. The open-label acute phase of a maintenance treatment study is informative in this respect (

24,

65). Patients who did not remit after 8 weeks of treatment with paroxetine could receive up to three open-label augmentation trials with bupropion, nortriptyline, or lithium. Sixty percent of those who received augmentation were in their first episode of depression, and with successive treatments, 50% of them achieved remission, suggesting a possible value of adjunctive medication in patients with late-life depression for whom initial treatment fails. In addition, maintenance treatment studies suggest the potential value of antidepressants in first-episode patients. Paroxetine with or without augmentation has been reported to reduce recurrence relative to placebo in many older patients in their first episode of depression (

24). In another maintenance study (

66), citalopram was found to be more effective than placebo in preventing recurrence during the 48-week randomized phase. In that trial, 85% of the patients had no prior episodes of major depression, which suggests that maintenance treatment may be of value for at least some first-episode patients. Alternatively, Wilson et al. (

67) did not find a significant advantage for sertraline relative to placebo in a 2-year maintenance trial in which 72% of participants were in their first episode. These studies indicate a potential role for medication in maintenance treatment of patients with first-episode late-life depression.

This analysis is somewhat unusual. Most individual-patient-level meta-analyses of depression treatment have been limited to trials conducted by one sponsor using their data. An exception is the Fournier et al. analysis of the effects of illness severity on antidepressant outcome (

28). In that analysis, the authors were able to obtain individual patient-level data from six of 23 trials in the domain selected. In the present analysis, individual patient data were obtained for all 10 of the published randomized controlled trials of second-generation antidepressants in outpatients over age 60 with major depression. To our knowledge, these trials represent the entire domain of randomized controlled trials that meet the defined criteria.

This study has some limitations. First, the analysis was limited to the data commonly collected in the 10 trials described. There may be other variables not commonly documented, such as cognitive deficits, that also moderate treatment response. These trials excluded patients with severe or unstable medical illness; however, stable medical illness was common. For example, in the Schneider et al. trial of sertraline (

52), 93% of the patients had medical illness, and the average number of medical disorders was 4.3. Such patients are representative of many older depressed outpatients. While the findings may not generalize to the frail elderly, it seems unlikely that this patient group would be more responsive to drug treatment.

Difficulties in determining the exact age at onset of major depression is another limitation, as none of the trials provided a detailed description of how this was ascertained. Categorizing illness duration as short (<2 years), moderate (2–10 years), or long (>10 years) may mitigate the imprecision of estimates of age at onset and provide sufficient accuracy. We also note that in these randomized trials, any biases and imprecision in these data are randomly distributed between treatments. These illness duration categories did identify subgroups with different drug-placebo characteristics. While requiring confirmation, the potential importance of illness duration in moderating drug-placebo differences in these trials underscores the need for reliable methods of assessing illness duration and suggests that this measure be routinely determined.

Another potential limitation of the data is the large effect of the study covariate on response. Such a variable reflects other aspects of the studies that are unaccounted for. We attempted to control for this in our regression model, which allowed us to examine the independent relationship of our variables of interest with response. In addition, while the variability of the study covariate could reflect design problems or measurement error, it could also indicate heterogeneity among the patients that could enhance generalizability.

Finally, we acknowledge that our examination of moderators is a post hoc exploratory analysis and may overemphasize patient and depression characteristics that are unique to this sample. The predictive value of the moderators and the model generated will require replication. As noted above, however, our findings are similar to those of previous meta-analyses and large trials with mixed-aged samples (

27,

28,

31,

32).

In summary, data from the seven placebo-controlled acute-phase trials conducted in late-life depression suggest that antidepressants are not effective in older patients with late-onset depression of short duration. Clinicians should reconsider the prevailing practice of simply prescribing an antidepressant in these patients. Antidepressants were effective, however, in patients with a longer duration of illness that was at least moderately severe. These moderators appear to be useful for tailoring treatment to the patient.