Early adverse experience dramatically increases the risk for developing a wide range of psychiatric disorders and certain medical diseases later in life (

1,

2). One common and exceptionally detrimental clinical consequence of childhood sexual abuse is the development of sexual dysfunction, including anorgasmia and inability to experience sexual pleasure, as well as chronic genital or pelvic pain in adulthood (

3,

4). The precise mechanism that mediates this association remains poorly understood. A burgeoning number of studies suggest that there is substantial plasticity of the human brain as a function of experience (

5). For instance, London taxi drivers have been shown to exhibit navigation-related structural increases in the posterior hippocampus, which is relevant to spatial representation of the environment, suggesting that the brain is capable of adapting its structure in response to environmental demands (

6). Another example of experience-induced neural plasticity is observed in limb amputees who exhibit cortical reorganization of the somatosensory cortex after the deprivation of afferent inputs, inasmuch as adjacent cortical representations of intact sensory parts invade the representation field of the lost sensory part (

7,

8). It has been suggested that constant cortical competition for space leads to enlargement of areas that are supplied with important information, whereas other areas are narrowed (

5). Although the adult brain has the capacity for neural plasticity, the developing brain is clearly more sensitive to the organizing effects of experiences. In classic studies, Wiesel and Hubel (

9) demonstrated that visual input during a sensitive period early in life is critical for normal development of the visual cortex and vision. Cortical plasticity during sensitive periods may also account for long-term effects of enriching early experiences. For instance, Elbert et al. (

10) reported that earlier onset of musical training during childhood is associated with larger cortical representation of the fingers of the left hand in the primary somatosensory cortex of string players. Extending the cortical competition hypothesis, it can be argued that neuroplastic reorganization may depend on the nature and timing of the experience. More specifically, if an experience is highly aversive and developmentally inappropriate (instead of enriching), the brain may not allocate more resources to the experience but instead narrow its cortical representation to limit detrimental effects.

We hypothesized that the experience of childhood abuse may lead to regionally highly specific neuroplastic thinning of cortical fields, depending on the precise nature of the abusive experience. Such cortical adaptation would serve to immediately shield the child from the experience of the abuse by gating the sensory processing. While initially protective, such cortical thinning may represent a direct biological substrate for the development of behavioral problems later in life, when the behavior in question, such as normal sexual perception, would be developmentally appropriate. Using MRI-based cortical thickness analysis, we demonstrate that different forms of childhood abuse are associated with profound and regionally highly specific cortical thinning, precisely affecting areas that are critical to the perception and/or processing of the specific behavior implicated in the type of abuse.

Results

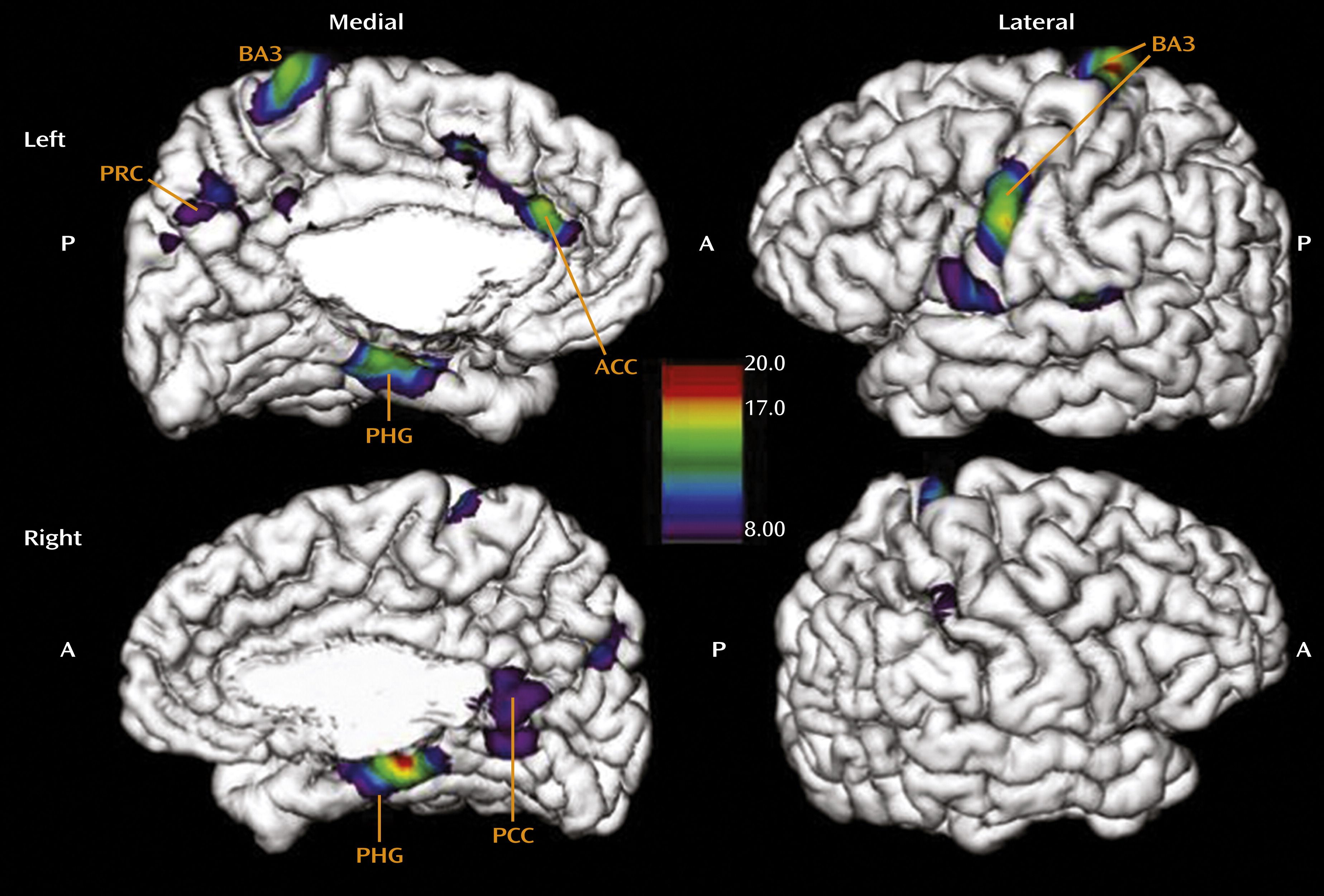

In the regression of cortical thickness against CTQ total score across all subscales, the results revealed a widespread effect of cortical thinning as a function of childhood adversity (

Figure 1). The area most prominently affected in the left hemisphere was the somatosensory cortex laterally (local maxima at Talairach coordinates x=−19, y=−31, z=78; F=19.3, p<0.001; x=−62, y=−7, z=34; F=16.4, p<0.001), in locations associated with sensory representation of the female clitoris and surrounding genital area as well as the mouth area (for details regarding the precise location of the somatosensory genital field as identified using functional MRI of neural response to stimulation, see references

22 and

23). Medially, our results indicated effects of the CTQ total score on thinning of the anterior cingulate gyrus (x=−2, y=36, z=18; F=12.7, p<0.001), the precuneus (x=−3, y=−60, z=45; F=8.4, p<0.01), and the parahippocampal gyrus (x=−18, y=−20, z=−18; F=13.6, p<0.001), structures mediating emotional regulation (

24), self-awareness (

25,

26), and memory encoding (

27,

28), respectively. In the right hemisphere, results were less pronounced, with one maxima in the right motor cortex laterally (x=14, y=−21, z=76; F=12.2, p<0.001) and in the area of index finger representation, the parahippocampal gyrus (x=17, y=−28, z=−13; F=18.8, p<0.001) and the posterior cingulate cortex medially (x=3, y=−52, z=16; F=8.9, p<0.01). The effects were maintained when we additionally controlled for PTSD. Because the CTQ total score summarizes the severity of five different types of maltreatment, these widespread effects on diverse brain regions likely reflect additive effects of several forms of abuse, which often co-occur, while specific effects of different forms of maltreatment were not considered in this analysis.

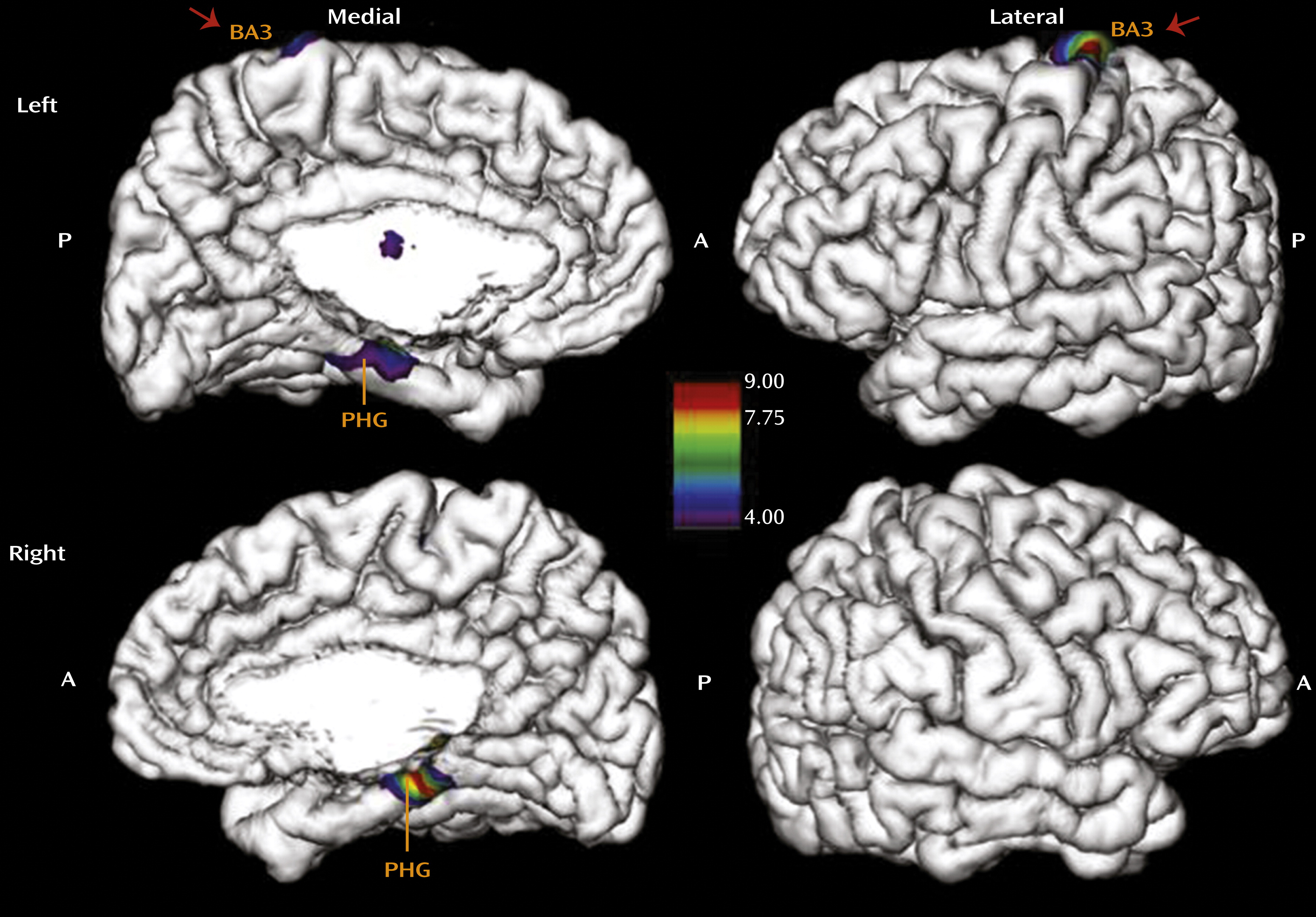

We therefore investigated whether the pronounced effect of total CTQ score on the somatosensory cortex in the genital representation field might be specific to childhood sexual abuse. To isolate the effects of sexual abuse on cortical thinning, we ran a separate analysis with the CTQ subscale score for sexual abuse as the main regressor, while controlling for age, depression, and the other four CTQ subscales entered as covariates (

Figure 2). This analysis revealed a highly specific effect of sexual abuse experience on thinning of the somatosensory cortex representing the female clitoris and surrounding genital area (x=−16, y=−32, z=76; F=8.6, p<0.01) in the left hemisphere (

22,

23). The parahippocampal gyrus in the left (x=−20, y=−17, z=−21; F=4.6, p<0.05) and right (x=17, y=−28, z=−14; F=8.9, p<0.01) hemispheres was also affected by sexual abuse. To further isolate the specific effects of different types of maltreatment on cortical thickness, we determined whether emotional abuse has a specific effect on cortical thickness that can be distinguished from the effect of sexual abuse (

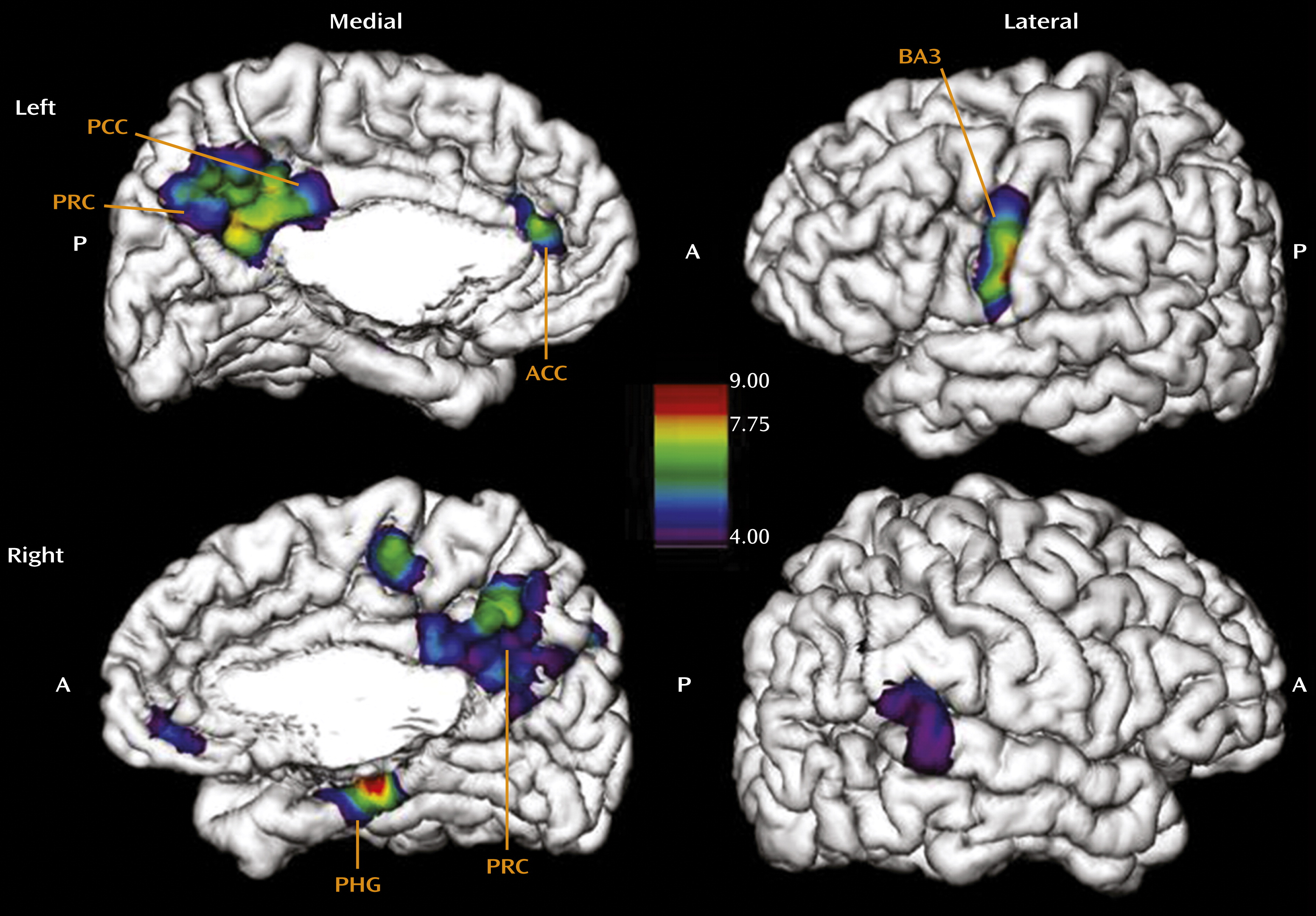

Figure 3). Indeed, emotional abuse specifically affects the areas of the left (x=−3, y=−61, z=45; F=7.8, p<0.05) and right (x=6, y=−49, z=51; F=6.2, p<0.05) precuneus and the left anterior (x=−4, y=40, z=11; F=6.9, p<0.05) and posterior cingulate cortex (x=−2, y=−47, z=28; F=8.1, p<0.01). We also observed thinning in the face region of the somatosensory cortex (x=−56, y=−12, z=45; F=22.7, p<0.001). Hence, emotional abuse, which likely represents experiences of parental rejection and is often considered most detrimental in terms of altered concept of “self,” is associated with the cortical thinning of regions implicated in mediating self-reflection, self-awareness, and first-person perspective (

24–

26).

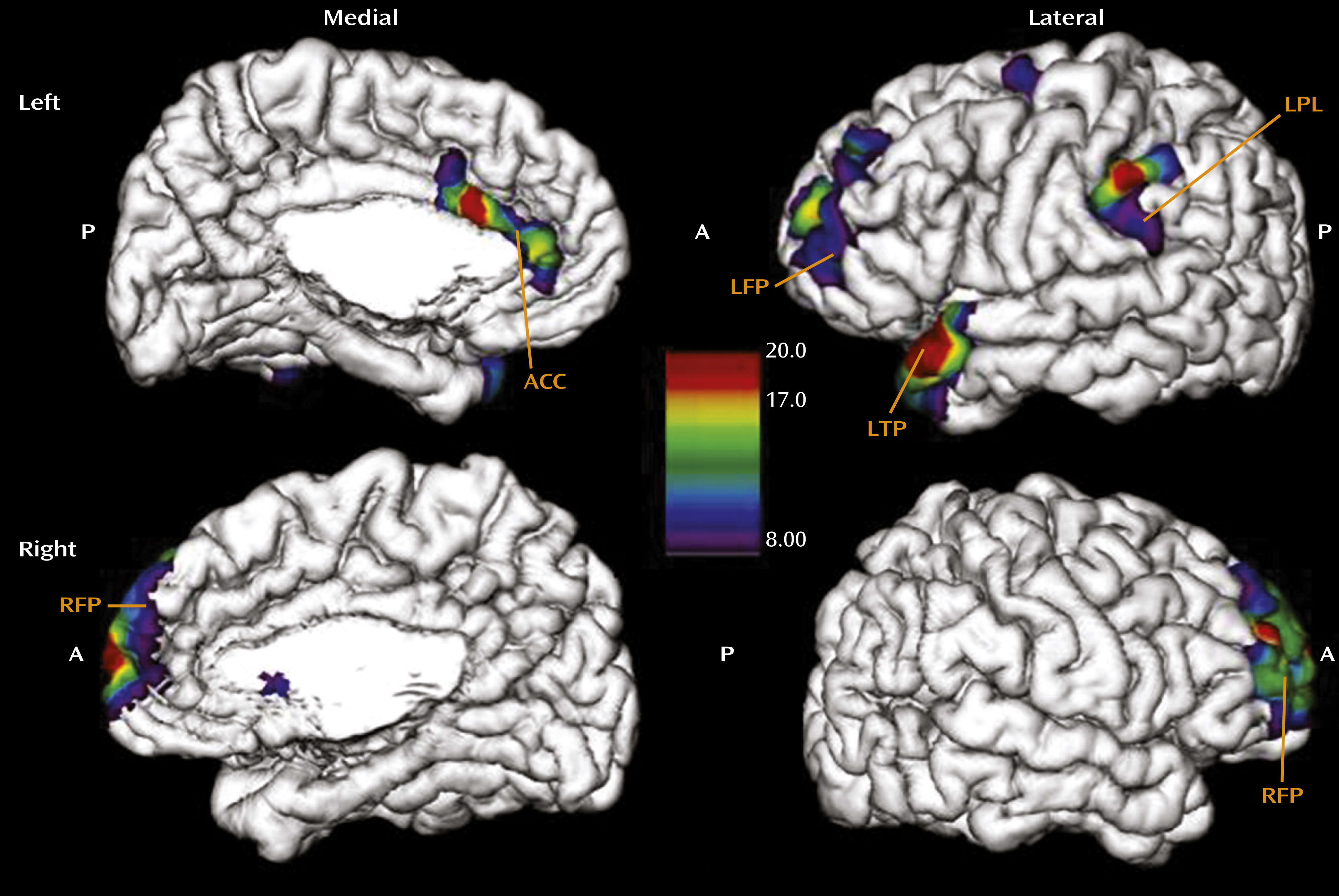

Finally, we investigated the effect of age at onset of any abuse on cortical thickness in the group of women reporting moderate to severe exposure. This analysis revealed that earlier exposure was associated with thinning of the left temporal pole (x=−49, y=22, z=−26; F=19.9, p<0.001), the left parietal lobe (x=−63, y=−32, z=45; F=18.9, p<0.001), the left frontal pole (x=−28, y=63, z=12; F=16.8, p<0.001), and the right frontal pole (x=11, y=69, z=4; F=18.6, p<0.001), areas associated with autobiographic memory, as well as thinning of the anterior cingulate cortex (x=−2, y=21, z=22; F=8.13, p<0.01) (

Figure 4). This finding is concordant with reports that abuse occurring earlier in childhood is often associated with absence of memories concerning the abuse (

29). We did not see an effect of duration of the abuse, which supports the assumption that the observed effects reflect developmental programming rather than consequences of cumulative exposure to maltreatment over time.

Discussion

Our results suggest that exposure to childhood adversity is associated with pronounced neuroplastic changes in the cortex in the form of cortical thinning that occurs in a regionally highly specific manner, determined by the type of maltreatment that was experienced. Because the study design was cross-sectional, a causal interpretation of these results is impossible. Nevertheless, our results suggest that early adverse experience is associated with neuroplastic adaptation resulting in altered cortical representation of sensory and processing areas that are directly implicated in the abusive experience. We suggest that cortical thinning in these regions may represent the most adaptive and protective response of the developing brain, potentially serving to shield the child from highly adverse environmental conditions by gating sensory experiences and processing related to the abuse. While this idea of sensory gating of abusive experiences is clearly speculative, the general principle of sensory gating is a well-known phenomenon that has been described in terms of filtering auditory input by personal relevance (

30) and in terms of gating acute pain stimuli at the level of the spine (

31). Whether or not abusive experiences can be gated in such ways is unknown, but this is an intriguing possibility raised by our results and should be further scrutinized.

A number of mechanisms may explain how excessively adverse sensory experiences might lead to impaired neurodevelopmental and hence structural change in adulthood. Although neocortical thickness is determined by the number of neurons as well as by the number of synapses and dendritic branches, the effects observed in this study likely reflect variations in synaptic density because the number of neurons in these cortical areas likely remains stable (

32). A study of monocular visual deprivation (

33) suggested that early deprivation leaves a long-term structural trace by increasing cortical dendritic spine density in the visual representation field of the opposite eye that outlasts the original experience and remains unaffected by subsequent experimental variation of visual input. Our observation of thinning in the primary somatosensory cortex after sexual abuse may be understood as a consequence of both top-down and bottom-up mechanisms.

Evidence for top-down mechanisms comes from studies investigating the role of painful stimuli on somatosensory cortex activation (

34,

35). These studies demonstrate that pain perception in the somatosensory cortex is subject to cognitive modulation. By directing attention away from the painful stimulus, activation of the area of the somatosensory cortex associated with the painful stimulus can be dramatically reduced. If such top-down cognitive modulation directing perception away from the painful stimulation occurs during the critical time of synapse formation and development, as can be envisioned when children experience sexual abuse, the final formation of synaptic connections in specific parts of the neocortex would be significantly decreased.

Complementary to the cognitive modulation theory is a potential bottom-up mechanism. Decreases in blood flow have been shown to occur in the somatosensory cortex as a consequence of painful stimulation. This has been demonstrated for noxious stimuli (

36) as well as for painful heat stimuli (

37). Physical and sexual abuse during the period of synapse formation might lead to inhibition, and as a consequence, the number of synapses in the somatosensory cortex might be reduced. The basic cellular mechanisms implicated in such inhibition have been reported to depend on long-term depression and potentiation, in conjunction with

N-methyl-

d-aspartate receptors in thalamocortical circuits (

38). Of note, the effect of sexual abuse on thinning of the somatosensory genital field was present only in the left hemisphere. Because the genitals are centralized in the body, this lateralization can be hypothesized to be based on central mechanisms of inhibition that may be lateralized. Future studies should scrutinize the origin of this lateralization.

Later in life, when the stimulation would be developmentally appropriate, the lack of development of the genital sensory representation field may lead to impaired sexual perception, explaining the frequent clinical reports of sexual dysfunction. However, in the absence of data linking cortical thickness with sexual behavior and the experience of sexual pleasure, we cannot further substantiate this notion. Decreased thickness of the genital sensory representation field may also contribute to genital or pelvic pain in women with a history sexual abuse, in light of studies showing that increased thickness of the somatosensory cortex is associated with increased pain threshold (

39), perhaps suggesting that less differentiated sensory processing decreases the pain threshold. Assuming similar mechanisms, the most affected cortical regions implicated in the processing of emotional abuse should be brain areas associated with emotional regulation and the perception and evaluation of one’s self, as observed in the present study. If adverse stimulation during critical developmental periods of emotional regulation circuits also leads to cognitive avoidance and inhibition in association with emotional processing, then the areas of the precuneus and cingulate cortex would be primary targets of such effects, given their dominant role in these functions. Of note, decreased anterior cingulate cortex volume has been reported in studies of adults with histories of childhood trauma, although these studies did not distinguish between different types of trauma (

40,

41).

An alternative explanation of our results might assume a reverse direction of effect. Individuals with sexual abuse experiences may avoid sexual contact in adulthood. Decreased frequency of sexual behavior may result in cortical thinning of the somatosensory representation field, in accordance with the general principle that connections that are less frequently used are diminished, while connections that are more often used are strengthened (

5). Similarly, emotionally abused children might grow into rejection-sensitive adults who avoid situations requiring evaluation of self and therefore underuse these cortical regions. In the absence of longitudinal MRI and behavioral data, we are not able to test the competing hypotheses, which is a limitation of the study. Another limitation is reliance on retrospective self-reports of childhood experiences, which may be hampered by simple forgetting, nonawareness, nondisclosure, and reporting biases. However, a recent meta-analysis of studies using external corroboration of self-reports revealed that false negative reports are more frequent than false positive ones, leading to downward biases in estimated associations between childhood abuse and outcome variables (

42).

In conclusion, our observations lend support for the hypothesis that neural plasticity occurs during development, as demonstrated by the thinning of cortical regions that mediate the sensory perception and processing of specific abusive experiences. We hope that our results will serve as an impetus for developing longitudinal and mechanistic studies designed to further scrutinize the association between childhood adversity and experience-dependent neural plasticity. Such studies have the potential to elucidate the biological basis of the detrimental behavioral effects of childhood trauma, which may lead to improved strategies for the prevention and intervention of disorders such as sexual dysfunction by targeting the substantial capacity of the human brain for neural plasticity.