SSRIs have been found to be associated with upper gastrointestinal bleeding (

3). The risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding can be further increased when SSRIs are combined with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (

4), antiplatelet agents (

5), or warfarin (

6). However, controversy remains regarding whether there is actually an elevated risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding with SSRI use (

7,

8). The reason for the conflicting results is unclear. The absence of consideration of comorbidities and insufficient sample sizes of SSRI users could result in a failure to observe an elevated risk for upper gastrointestinal bleeding after SSRI exposure. Furthermore, a 3-month window is usually adopted in studies that evaluate the risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in SSRI users. To date, the risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding after short-term SSRI exposure remains unclear. Within 7–14 days after starting SSRI, the intraplatelet serotonin concentration decreases by more than 80%, resulting in impairment of platelet aggregation (

9–

11). Within hours, SSRI use increases gastric acid secretion in rodents, which may potentiate the bleeding risk in the gastrointestinal tract (

12). There has been a case report of upper gastrointestinal bleeding after only 7 days of SSRI exposure (

3). Such observations prompted us to test the hypothesis that short-term SSRI use increases the risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. To overcome the potential biases stemming from inadequate control for comorbidities and underpowered sample sizes, we applied a case-crossover design in patients with psychiatric diagnoses from Taiwan’s nationwide population-based claims database.

Results

In a total of 187,117 patients who were included in the NHIRD-PIMC database from 1998 to 2009, 5,500 patients who were older than 20 years of age had new-onset episodes of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. We excluded 123 patients with concomitant trauma or esophageal variceal bleeding, leaving 5,377 patients for the analysis. The patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics are summarized in

Table 1.

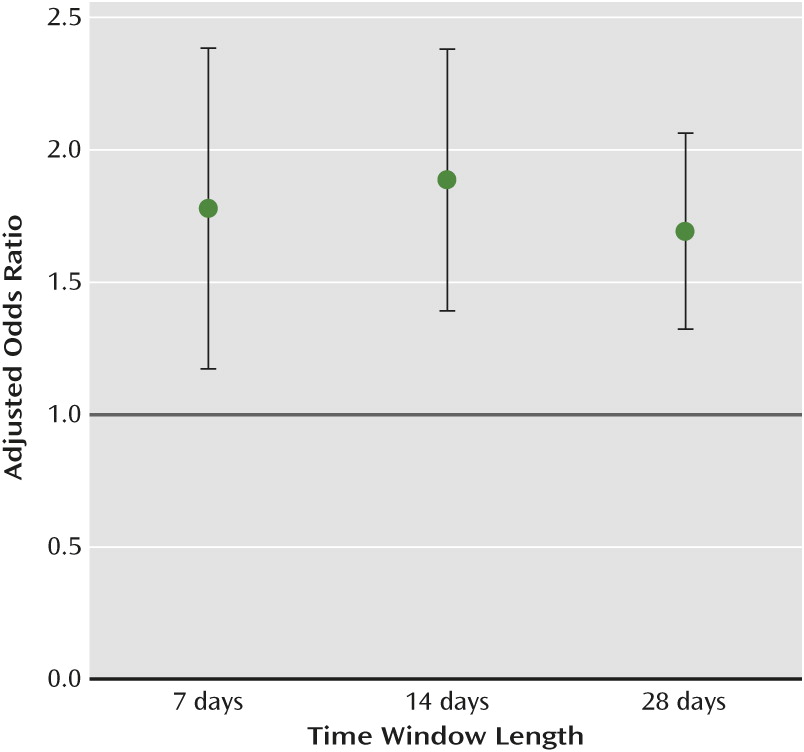

SSRIs were the only antidepressants associated with an elevated risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding after we adjusted for the time-varying confounders (

Table 2). An elevated risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding was identified for all three time windows for SSRI users, with a higher value in the 14-day window. An analysis of fluoxetine (adjusted odds ratio=1.68, 95% confidence interval [CI]=1.10–2.57) and sertraline (adjusted odds ratio=1.87, 95% CI=1.16–3.02) showed an elevated risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding, while for other SSRIs the elevation in risk fell short of statistical significance (

Table 3). In the 14-day time window, the demographic data and distribution of comorbidities were similar between the control group (patients taking drugs in the control period but not in the case period) and the case group (patients taking drugs in the case period but not in the control period). Charlson comorbidity index score also did not differ significantly between the two groups (3.7 [SD=2.9] and 3.8 [SD=2.9], respectively). The frequencies of health care utilization before the index date were similar between SSRI users and users of other antidepressants (a median frequency of 32 for both groups for ambulatory care, and a median frequency of 2 for hospitalization for both groups).

Antidepressants with high (adjusted odds ratio=1.75, 95% CI=1.31–2.34) and intermediate (adjusted odds ratio=1.74, 95% CI=1.23–2.45) serotonin transporter affinity were associated with an elevated risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding, but not antidepressants with low affinity (adjusted odds ratio=1.27, 95% CI=0.94–1.72) (see Figure S1 in the online

data supplement). SSRIs showed no dose-response relationship for risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding (the adjusted odds ratios were 2.23 [p=0.08], 2.47 [p<0.001], 1.59 [p<0.010], and 1.75 [p=0.002] for <0.5, 0.5–1.0, 1.0–2.0, and ≥2.0 defined daily doses/day, respectively).

The effects of the interactions of SSRIs with NSAIDs and aspirin on the risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding are summarized in

Table 4. An elevated risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding was observed in patients who were taking NSAIDs, SSRIs, or aspirin alone, with adjusted odds ratios ranging from 1.77 to 1.97. For patients taking SSRIs with aspirin, the risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding increased slightly, to an odds ratio of 2.07. The highest upper gastrointestinal bleeding risk was observed with the combination of SSRIs and NSAIDs (adjusted odds ratio=3.44). The combination of all three drug types (SSRIs, NSAIDs, and aspirin) did not further increase the risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding (adjusted odds ratio=3.27). Neither benzodiazepines (adjusted odds ratio=1.18, 95% CI=0.34–1.66) nor nonbenzodiazepine hypnotics (adjusted odds ratio=1.16, 95% CI=0.79–1.69) were associated with an elevated risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

In subgroup analyses, the risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding was significantly elevated in males (adjusted odds ratio=2.43, 95% CI=1.75–3.38) but not in females (adjusted odds ratio=1.01, 95% CI=0.63–1.61). The risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding was more easily observed in patients who were under age 55 (adjusted odds ratio=2.13, 95% CI=1.45–3.12), those who had a history of upper gastrointestinal tract diseases (adjusted odds ratio=3.17, 95% CI=1.70–6.00), and those who had no history of previous SSRI use (odds ratio=2.64, 95% CI=1.55–4.24). The bleeding risk was not associated with the patients’ comorbidities.

Discussion

In this case-crossover study, we provide new evidence that short-term exposure (7–28 days) to SSRIs is associated with a significant risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding, a phenomenon similar to the short-term use of NSAIDs and antiplatelet agents.

Most previous studies exploring the effect of long-term (3 months) SSRI use on the risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding were cohort, case-control, or nested case-control studies, which presented conflicting results (

7,

25–

27). The inconsistent conclusions may be due to the differences in enrollment criteria and matching strategies. Many of the previous studies did not take into consideration confounders (such as lifestyle factors and comorbidities) in the SSRI users or the patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding (

25,

27). Lifestyle factors such as alcoholism, smoking, and mental status are associated with peptic ulcer disease and even with a higher risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding with or without SSRI exposure (

28). Knowledge of these factors was typically unavailable or was not recorded in previous retrospective population studies. Some studies did not match with comorbidities (

4,

26), while others did report comorbidities but with uneven distribution between case and control groups, which may adversely affect the final results (

7,

8). To overcome this potential bias, we used a case-crossover design to assess the risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding during a short interval (7–28 days) after SSRI exposure (

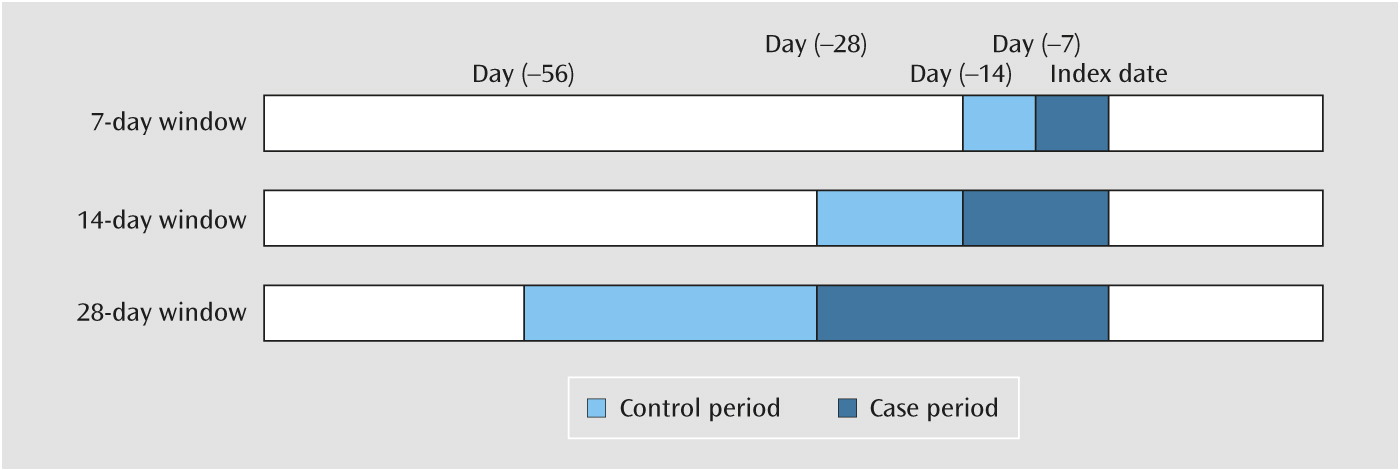

13). Because lifestyle and the presence of chronic comorbid illnesses were unlikely to change during such a short period, the only differences between the case and control periods were the time-varying factors (medications). With this measurement, most of the unmeasured confounding factors that could cause selection bias would be eliminated.

We found that SSRIs were associated with an elevated risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in all three time windows. The risk after 14 days of exposure was higher than that for the 7- and 28-day windows, although the adjusted odd ratios overlapped (

Figure 2). Multiple mechanisms may be involved in this association. Within 14 days of use, SSRIs can significantly reduce intraplatelet serotonin concentration (83% decrement) and impair platelet plug formation (

9–

11). SSRIs can also directly induce mucosal damage in the gastrointestinal tract and stimulate gastric acid secretion in rats within hours, which may potentiate the risk for upper gastrointestinal bleeding (

29,

30). Our finding that the patients with preexisting upper gastrointestinal tract disease were predisposed to bleeding after short-term SSRI exposure further supports this observation.

In this study, we focused on patients with psychiatric diagnoses from a national population-based claims database. We believed that this specific group of patients served as an ideal group to test our hypothesis. First, in previous studies addressing the effects of SSRIs on the risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding, the conclusions were almost always based on general-population data. These patients were usually highly exposed to other drugs related to bleeding (such as aspirin and NSAIDs), but a low percentage were SSRIs users (approximately 3% in the studied population) (

6,

25). The role of SSRIs in the risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding might be underestimated in patients with these conditions. Second, patients with psychiatric diagnoses constitute the main subpopulation that uses SSRIs, and their treatment course would be more regular and longer and would involve higher dosages compared with the general population. Thus, with the data set we used in this study, our results may better reflect the real effect of SSRIs on the risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

Among the various SSRIs, fluoxetine and sertraline were both associated with an elevated risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Although other SSRIs (citalopram, paroxetine, and escitalopram) were also associated with an elevated bleeding risk, the relationships fell short of statistical significance. We believe this may be due to the modest risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding after SSRI exposure and the underpowered sample size for each individual SSRI, even though the number of individual drugs in this study outnumbered those in previous reports (

25,

26). However, this assumption cannot be warranted until confirmed by studies with large enough subsamples of patients taking individual SSRIs.

Short-term exposure to tricyclic antidepressants, SNRIs, MAO inhibitors, and other antidepressants was not associated with an elevated risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. This finding suggests that these drugs might serve as alternatives to SSRIs in psychiatric patients with a history of gastrointestinal bleeding or peptic ulcer disease. Before the era of proton pump inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants were used to treat peptic ulcer disease because of their anticholinergic and antihistamine effects (

31). Mirtazapine also has antiulcer effects in rats and has fewer gastrointestinal side effects owing to its blocking effect on 5-HT

2 and 5-HT

3 receptors (

32).

We found that male, but not female, SSRI users had an elevated risk for upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Previous studies have found that females have a lower but still significant risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding compared with males after SSRI exposure (

7,

26). Our results are in accord with a recent large-scale study showing that only male patients had a heightened risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding following acute myocardial infarction after exposure to an SSRI and antiplatelet agents (

5). There are several possible explanations for this finding. First, serotonin blood levels are higher in females than in males, because estradiol can stimulate serotonin uptake by platelets (

33). Second, estrogen can stimulate platelet aggregation, resulting in higher platelet aggregation activity in females compared with males (

34). Additionally, male gender is a risk factor for peptic ulcer disease, and the gastric microenvironment is more acidic in males than in females (

35), which may also contribute to the gender differences in the risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding after SSRI exposure. However, we should be careful in the interpretation of this result, because the power to detect a difference between case and control subjects in the female subgroup was inadequate in this study.

Although SSRIs are widely used in the treatment of depression and anxiety disorders, SSRIs can still be associated with significant side effects. For example, suicidality, birth defects, neonatal withdrawal syndrome, sexual disturbance, hyponatremia, weight gain, insomnia, and gastrointestinal bleeding have been associated with long-term SSRI use (

36). Traditionally, short-term side effects of SSRI, such as nausea, diarrhea, headache, and agitation, are usually considered mild and subside after 2–3 weeks. However, this study demonstrated that short-term SSRI exposure (as little as 7 days) increased the risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. The extensive use of SSRIs has been criticized by some who question whether it is worthwhile to trade questionable symptom relief for these potentially serious and bothersome side effects, particularly when evidence-proven alternative interventions are available (

37). Given the relatively high incidence of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in the general population (36–172 per 100,000) and the associated high mortality rate (2.4%−10%) (

38), we suggest that physicians make treatment decisions on an individualized basis by balancing the potential side effects and treatment responses when prescribing SSRIs. Close monitoring of signs of gastrointestinal bleeding may be warranted soon after beginning SSRI treatment.

This study has several limitations. First, the exact reasons for SSRI prescriptions were not known. Prescription of an SSRI could be due to stressful life events, neuroticism, and anxiety. These psychological events are linked to the pathogenesis of peptic ulcer disease and might predispose the individual to upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Thus, these psychological factors may also contribute to upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Second, because patients’ identities were hidden for privacy protection, no information was available in the NHIRD about their adherence to the prescriptions, which is an inherent limitation of all studies using claims data. Nevertheless, previous information from official databases has shown high concordance between actual prescription adherence and self-reported medication use (

39). In any case, nonadherence would eventually lead to underestimation of the actual risk. Finally, this study mainly focused on inpatients with psychiatric diagnoses whose illnesses are likely to be on the severe end of the spectrum. Our findings may or may not extend to patients with nonpsychiatric diagnoses.