Recent findings suggest that disability due to psychiatric impairment may be at least partially reversible. Many people with serious mental illnesses such as schizophrenia and mood disorders experience long-lasting periods of stability while using currently available interventions, such as team-based care (

1) and appropriate medication management (

2). In addition, new vocational services, such as the individual placement and support model of supported employment, have demonstrated a robust ability to help people with mental illnesses return to competitive employment (

3). People with serious psychiatric impairments need both evidence-based treatments and vocational services to maximize participation (

4,

5).

The Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) program provides long-term income support and access to Medicare (after 24 months) to individuals who have been employed but are no longer able to work because of impairment. SSDI is the largest disability program in the United States, with monthly payments to more than 8.5 million working-age beneficiaries in 2011 (

6). The SSDI rolls tripled between 1980 and 2010 (

7), and the largest and fastest-growing group of SSDI beneficiaries, approximately 28% of the total, have psychiatric impairments, primarily psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia and mood disorders such as bipolar disorder and depression (

8). Regardless of the category of impairment, less than 0.5% of SSDI beneficiaries leave the Social Security rolls each year because of a return to work (

9). As a result, SSDI expenses exceeded $132 billion in 2011 (

10). Disability due to psychiatric impairments has become a major contributor to rapidly increasing SSDI Trust Fund expenses (

7).

SSDI beneficiaries may be particularly good candidates for an intervention that combines evidence-based treatments and employment services because they generally have a substantial employment history, which is usually a good predictor of future employment (

11). Once on the disability rolls, however, they have typically received suboptimal rehabilitation services and mental health interventions, in part because of the limits of Medicare coverage. Optimal interventions may improve their mental health status, decrease their impairments, and reduce or eliminate their disabilities.

Method

The MHTS enrolled 2,238 SSDI beneficiaries in a randomized controlled trial at 23 study sites dispersed throughout the United States. The intervention, based on the chronic care model (

13) and implemented at each site using a multidisciplinary team of providers, included three main components: the individual placement and support model of supported employment, systematic medication management, and other behavioral health services. To remove obvious barriers to participation, the SSA provided participants in the intervention group with complete health insurance coverage with no out-of-pocket expenses and suspension of continuing disability reviews for 3 years, because these reviews may deter efforts to return to work. The SSA paid for all of these services and cost-sharing reimbursements. The control group received the same services they had been receiving prior to enrolling, that is, services as usual. Several university and other institutional review boards approved and monitored the study, and all participants provided written informed consent at enrollment.

Participants

Inclusion criteria were being an SSDI beneficiary with a primary diagnosis of schizophrenia or a mood disorder, being interested in gaining employment, being 18–55 years of age, and residing within a 30-mile radius of one of the study sites. Exclusionary criteria were residing in a custodial setting (such as a nursing home), having a legal guardian, having a life-threatening physical illness that would preclude participating in the study, being currently competitively employed, and already receiving supported employment from the study site.

Procedures

Researchers recruited SSDI beneficiaries into the study through invitation letters, follow-up telephone calls, and informational groups. A computer-generated randomization at each site assigned participants to intervention or control groups. Research interviewers assessed employment, mental health, physical health, and quality of life at a baseline interview and at each of eight quarterly follow-up interviews. In addition, participants in the intervention group received a diagnostic interview (the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV) and a physical examination at baseline.

The intervention group teams reorganized care to provide supported employment, systematic medication management, and other behavioral health services. A nurse coordinated care at each site. Supported employment adhered to the individual placement and support model, which emphasizes team-based care, participant choice of jobs, benefits counseling, rapid job search, job development, and ongoing supports as needed (

14). Systematic medication management followed pharmacological management guidelines for depression, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia developed in the Texas Medication Algorithm Project (

15). Implementation of the guidelines, overseen by a nurse care coordinator, included use of manuals for each specific illness, standardized forms to document medication history and effects, quantitative symptom rating scales to measure outcomes, and medication recommendation options based on stage of illness, response, and medication history. Participants in the intervention group transferred to team psychiatrists or continued with their previous medication prescribers outside of the intervention team according to their preferences, and a nurse care coordinator invited all prescribers to collaborate on implementing systematic medication management. The teams delivered other needed behavioral health interventions, such as case management, substance abuse treatment, and family education and support (

16).

Medicare, other existing insurance, or study funds paid for services for intervention group participants. The research team monitored quality of care through ongoing training, interactions with nurse care coordinators, site visits and fidelity reviews by quality monitors, regular conference calls, and automated monitoring measures. The study provided transition planning during the final 4 months of the intervention group’s participation to ensure continuity of care. For the control group, usual care typically included the services covered by Medicare, such as outpatient physician visits, medications, and hospital care.

Measures

The primary outcome measure was employment status, and secondary outcome measures were mental health status and quality of life. Employment included any paid employment (all earnings were of interest to the SSA) and competitive employment, defined as mainstream jobs in integrated work settings at usual wages with regular supervision. Research interviewers assessed employment status using a computer-assisted timeline follow-back calendar at baseline and quarterly interviews. Although the primary outcome measure was rate of any paid employment, the follow-back calendar method yielded data on competitive employment, length of employment, hours per week of employment, and wages. Job satisfaction was assessed using the 36-item Indiana Job Satisfaction Scale (

17). The 12-item Short-Form Health Survey (

18), a self-report assessment of health derived from the 36-item version (

19), yielded a mental component score and physical component score to assess mental and physical health status. To assess quality of life, we used the overall life satisfaction item from the Quality of Life Interview (

20). Quality monitors assessed adherence to the individual placement and support model using the 15-item Individual Placement and Support Fidelity Scale (

21,

22).

Statistical Analysis

We used standard univariate tests (t tests and chi-square tests) to compare the intervention and control groups. We examined group equivalence through comparison of baseline characteristics. The main outcome analyses were endpoint analyses using cumulative outcomes for employment and services and change measures for scales.

We compared the groups at baseline and each month or quarter of study participation using univariate tests of independent proportions. In addition, a multivariate test examined the overall significance of the monthly employment rates using PROC GLIMMIX in SAS (

23), a statistical package employing generalized linear mixed-effects models for either continuous or categorical longitudinal or clustered data. Because competitive employment and paid employment are binary variables, this analysis used random-effects logistic regression, examining the group effect (intervention versus control), time effect (25 monthly observational periods), and group-by-time interactions.

Some participants dropped out of the study or completed follow-up interviews sporadically, and we used two methods to address attrition and missing data. First, we considered participants who did not complete at least two (of eight) postbaseline interviews (N=159) nonrespondents and adjusted weights to zero for nonresponse. Second, we used imputation procedures to address other participants with missing data and adjusted weights for nonparticipation in all interviews. Imputation procedures combined traditional methods for hot deck imputation with modern model-dependent chained parametric procedures (

24). An additional 24 participants (11 in the intervention group and 13 in the control group) died during the study and were excluded from analyses.

Results

Participants

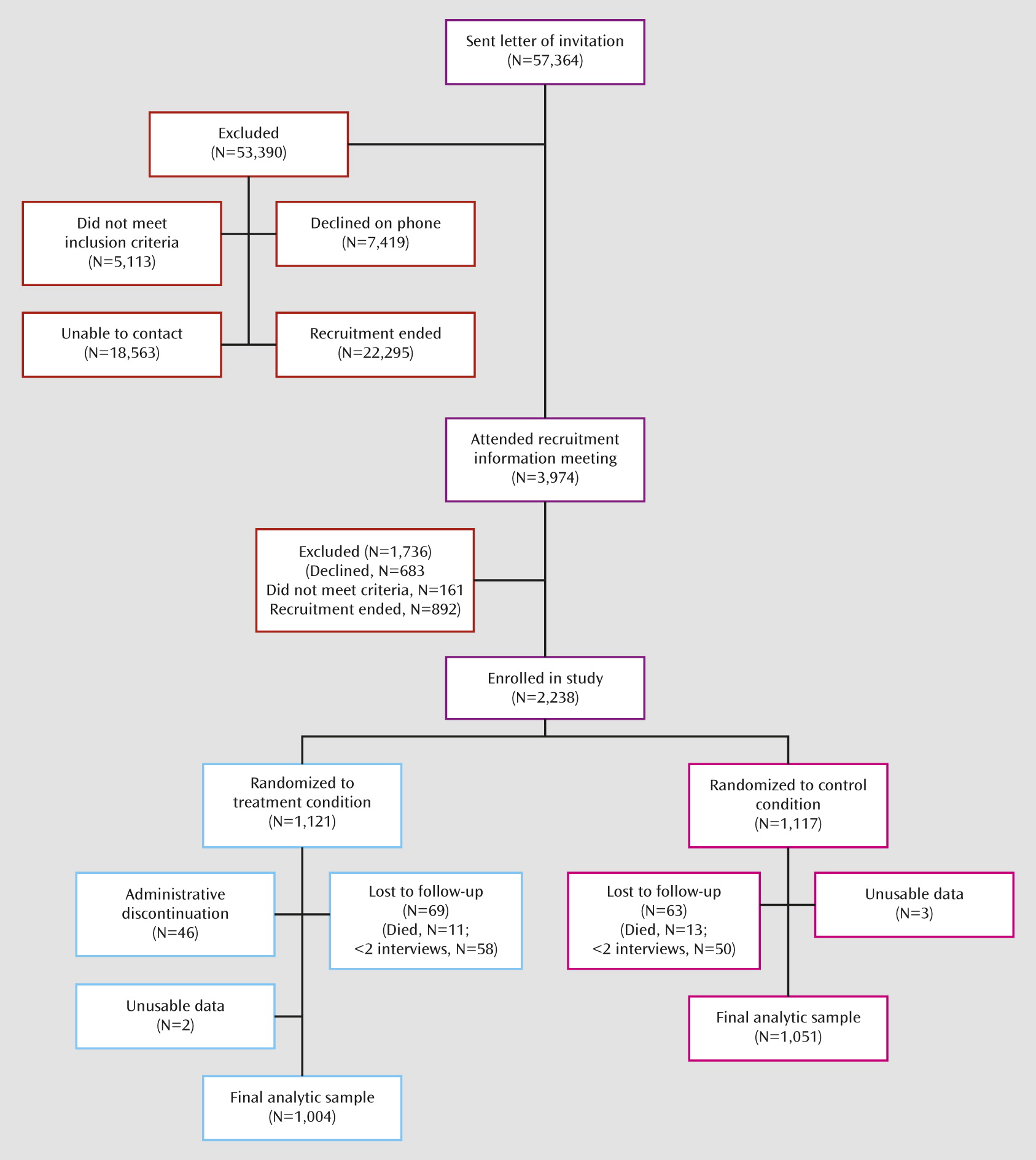

As shown in Figure 1, the CONSORT diagram for recruitment, 14% (2,238 of 15,982) of eligible beneficiaries who were contacted and invited to participate in the study agreed to join. Compared with nonparticipants, participants were younger on average (43.5 years compared with 47.9 years), had been on SSDI for a shorter period (97.9 months compared with 148.0 months), and had recently tried to work more often, as indicated by reporting earnings (17% compared with 4%), participating in the Ticket to Work program (2.8% compared with 0.3%), or having a trial work period ending within the past 3 years (2.6% compared with 0.9%).

Table 1 summarizes participants’ background characteristics, including demographic, employment, and clinical measures. The groups differed on few measures; the intervention group had a slightly higher percentage of participants with a diagnosis of schizophrenia than the control group, and there was a small difference between groups in racial background.

Attrition reduced the study group size to 2,055 (91.8% of baseline): 1,004 (89.6%) in the intervention group and 1,051 (94.1%) in the control group. Administrative discontinuations occurred in the intervention group (N=46) because some beneficiaries refused to undergo the physical examination mandated by the SSA. Interview completion rates remained over 80% up to the 24-month follow-up (N=1,893 [84.6%] overall; N=902 [80.5%] in the intervention group and N=991 [88.7%] in the control group).

Implementation

Quality monitors assessed program-level fidelity to the individual placement and support model in each of 3 years during the study. The majority of sites achieved high fidelity: 77% in the first year, 86% in the second year, and 86% in the third year; 98% of the annual fidelity ratings were fair or high.

Nurse care coordinator ratings of intervention participants’ engagement in systematic medication management indicated that 90.4% received this intervention during at least one of eight reporting periods, and 57.3% received the intervention during each reporting period. A total of 492 (50.5%) prescribers (nurse practitioners or physicians) were employed at the study sites, compared with 482 (49.5%) prescribers who were in private practice or employed by another agency outside of the study sites. On-site prescribers participated more consistently in systematic medication management (83.8% moderately or fully engaged) than off-site prescribers (28.5% moderately or fully engaged), as rated by the nurse care coordinators.

Outcomes

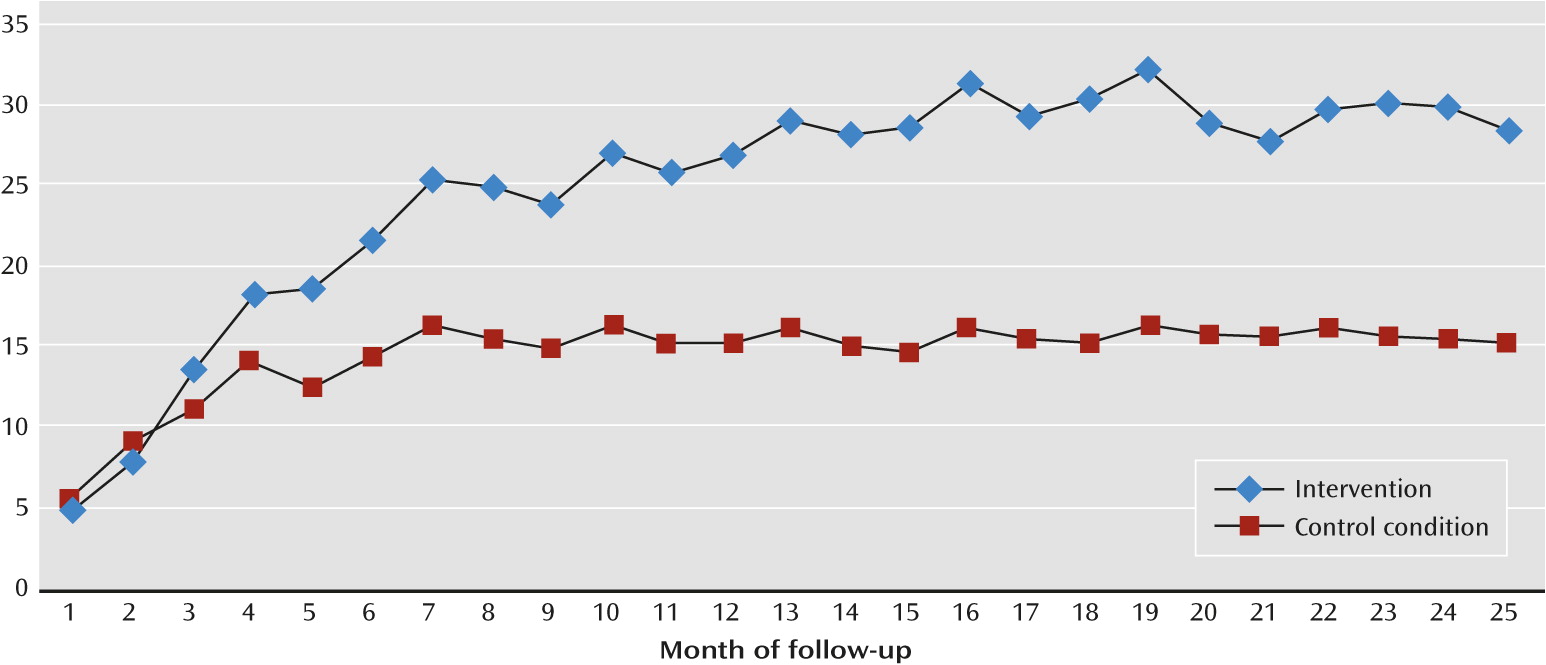

Figure 2 shows monthly rates of paid employment for the two groups. Starting in month 5, the intervention group had significantly higher employment rates during each month of follow-up. Rates of employment increased sharply for the intervention group from month 1 through month 7 and continued to increase modestly to over 30% until month 19. By contrast, the monthly employment rate for the control group plateaued starting in month 7 at 15% and remained static thereafter. From month 7 through month 25, the intervention group averaged a monthly employment rate of 28.3%, compared with 15.6% for the control group. Random-effects logistic regression showed the overall differences between groups in monthly employment rates for the 25-month period. The type III tests of fixed effects showed a significant group effect (F=55.95, df=1, 2053, p<0.0001), a significant time effect (F=17.14, df=24, 49272, p<0.0001), and a significant group-by-time interaction (F=2.17, df=24, 49272, p=0.001). All group and group-by-time effects favored the intervention group.

Results for monthly competitive employment (not shown) were generally similar to those for paid employment, except that the group-by-time effect was not statistically significant. From month 7 through month 25, the intervention group averaged a monthly competitive employment rate of 22.3%, compared with 12.1% for the control group.

Table 2 summarizes vocational outcomes.

The rate of paid employment at any time during the follow-up period was significantly higher for the intervention group than for the control group (60.3% compared with 40.2%), as was the competitive employment rate (52.4% compared with 33.0%). In the total sample, the intervention group had significantly greater paid employment outcomes than the control group. In the workers-only sample—that is, participants who obtained at least one paid job during the study—the intervention group had better outcomes than the control group on three measures (months employed, consecutive months worked at study exit, and job satisfaction at study exit), while the control group averaged a significantly earlier start date after study admission for their first paid job than the intervention group. Findings for competitive jobs (not shown) generally paralleled those for paid employment.

Few of our participants (less than 3% in the intervention group and less than 2% in the control group) had monthly earnings at or above the SSA’s threshold for substantial gainful activity, which increased from $900 to $1000 in 2010. In addition, few had earnings between 75% and 99% of this threshold. In fact, only three beneficiaries (0.15%) worked above substantial gainful employment in the last month of all eight quarters of follow-up, and only one beneficiary (0.05%) worked just below this level in the last month of all eight quarters.

Participants reported their use of health and mental health services at each quarterly interview, including overnight hospital stays, days in the hospital, emergency department visits, outpatient psychiatric crisis or psychiatric emergency center visits, and other (i.e., routine or ongoing) clinic or mental health provider visits. As shown in

Table 3, the intervention group had a consistent pattern of lower use rates than the control group for all but one indicator (other clinic or mental health provider visits), although the magnitudes of the differences were often relatively small. In contrast, outpatient visits to other clinics or mental health providers were about 46% higher for the intervention group, presumably a direct result of the engagement in the intervention.

Table 4 compares the intervention and control groups on changes in self-reported measures of health and life satisfaction. The intervention group reported greater improvements on average than the control group in mental health and life satisfaction, but not in physical health.

Discussion

From the perspective of a randomized controlled trial, this complex intervention demonstrated superiority over usual care on every important employment and mental health outcome: more workforce participation, more earnings, better self-reported mental health, and better quality of life. Although no change in physical health status occurred, none was expected. Individuals in the intervention group used fewer services of all kinds except for the outpatient mental health and vocational services that were the evidence of engagement in the intervention. What do these results tell us about the policy implications of the MHTS? To whom do the results generalize? How likely are SSDI beneficiaries with psychiatric impairments to participate in such an intervention? What is the feasibility of implementing this intervention? What is the likelihood of reducing social costs and reliance on public benefits?

Several findings from the MHTS should inform policy makers. First, because of its size and other features, this trial might be viewed as the definitive study of the impact of individual placement and support on employment. Other studies currently under way are examining the application of individual placement and support to different populations, interventions for nonresponders, and the expansion of individual placement and support through behavioral health technology, but the basic issue of effectiveness relative to other interventions has been resolved by more than a dozen randomized controlled trials (

3).

Second, a significant minority of invited SSDI beneficiaries (relatively younger ones, those who have been on the rolls for shorter periods, and those who had previously demonstrated interest in working) entered the study. Because only a small percentage of SSDI beneficiaries with psychiatric disabilities joined a study that offered an attractive package of service and insurance benefits, we infer that the majority of SSDI beneficiaries were not interested in changing their employment status, for various reasons. The literature suggests that fear of losing benefits may have been a major deterrent (

25). Other recruitment procedures might produce a higher rate of interest in employment, but a large increase seems unlikely based on previous studies of SSDI beneficiaries (

26). The 14% enrollment finding narrows the generalizability of the findings to a minority group of SSDI beneficiaries who are highly motivated to work.

Third, work history and behavioral motivation (e.g., actively participating in finding a job) consistently predict employment success among those receiving supported employment services (

11,

27). SSDI beneficiaries with these characteristics in the MHTS were highly successful in returning to work, which suggests that self-selected SSDI beneficiaries could return to some level of competitive employment and that the SSA could develop a targeted strategy to engage such individuals in treatment and supported employment.

Fourth, the complex intervention, which involved reorganizing services in line with the chronic care model, adding staff, providing supervision in evidence-based practices, and enhancing insurance coverage, was implemented and sustained over 3 years. The teams received considerable help with implementation: 2 days of initial training, organizational assistance from nurse care coordinators, telephone backup from implementation experts, and occasional fidelity visits. With these supports, in the midst of a financial crisis in public mental health services related to an economic recession, nearly every team was able to implement and sustain supported employment, systematic medication management, and team-based mental health care. Paying the centers a bundled rate for services not covered by insurance was also implemented relatively easily.

Fifth, those who received the intervention package increased their involvement in outpatient services, had a high rate of returning to paid (and usually competitive) employment, and experienced improvements in mental health status and quality of life. Those who became employed tended to work part-time, rarely worked enough hours to leave the Social Security rolls, and rarely worked near the level defined by the SSA as substantial gainful activity (the level at which benefits could be terminated after a trial work period). These findings are in accord with the literature on randomized controlled trials of individual placement and support (

3). In addition, workers with psychiatric impairments in long-term follow-up studies have consistently reported that working part-time helped them structure their lives, feel better about themselves, and manage their illnesses (

28). A key outcome for these workers is social inclusion—participating meaningfully in integrated work settings rather than being segregated in mental health settings.

Sixth, the MHTS provided somewhat negative results for those who hoped that assertive treatment and rehabilitation would result in savings for public benefit programs. Graduating SSDI beneficiaries from the disability rolls was not an initial goal of the study, but it emerged as an outcome of interest because of the recession and rising concerns about the SSDI Trust Fund. The part-time work patterns and modest earnings that we documented (an average of $1,778 per year for the intervention group and $1,169 per year for the control group, for a $609 difference) would not graduate people from the SSDI rolls. Whether beneficiaries would work at higher levels if health insurance were completely separated from disability status remains unknown.

The MHTS interventions might also yield savings in health and mental health treatments if employment replaced mental health services, as has been found in other studies (

29). Our evidence was incomplete, however. We did not collect detailed comparative data on costs of services for the two study groups, and the power to detect group differences was diminished by skewed distributions for hospital and emergency service use data. The observed pattern of results points to an intervention effect in terms of shifting services for the intervention group away from episodic, crisis-oriented services and toward ongoing management of their disorders on an outpatient basis, but a clear assessment of the service cost consequences of the intervention would require more detailed cost data and a longer follow-up period.

Seventh, although we learned in the field that SSDI beneficiaries had high rates of comorbid medical problems, the intervention did not address this aspect of their care, and we observed no improvements in physical health outcomes. The high rate of medical comorbidities and the related mortality among people with serious mental illnesses have been widely recognized (

30), and numerous studies are addressing the need to integrate mental and physical health care (

31).

Finally, aspects of the intervention model, the insurance changes, and other specifics were difficult to assess separately because the intervention in this study was a single multifaceted package. Other limitations include self-reported outcomes, the costs of implementation, and the difficulties in engaging outside prescribers in systematic medication management.

In conclusion, for a subset of SSDI beneficiaries with mental health disabilities and interest in employment, the intervention improved beneficiaries’ employment, mental health, and quality of life, even if it did not reduce short-term costs for public benefit programs.