Adult Diagnostic and Functional Outcomes of DSM-5 Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder

Abstract

Objective

Method

Results

Conclusions

Method

Participants

Childhood and Adolescent Psychiatric Status

Adult Psychiatric and Functional Outcomes

Psychiatric status.

Health functioning.

Risky or illegal behaviors.

Financial and educational functioning.

Social functioning.

Analytic Strategy

Results

Descriptive information

| Noncase Comparison Subjects | Psychiatric Comparison Subjects | DMDD Case Subjects | DMDD Case Subjects and Noncase Comparison Subjects | DMDD Case Subjects and Psychiatric Comparison Subjects | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | N | % | N | % | N | % | Odds Ratio | CI | p | Odds Ratio | CI | p |

| Female | 436 | 51.2 | 161 | 40.0 | 33 | 50.6 | 1.0 | 0.5–2.2 | 0.95 | 0.7 | 0.3–1.5 | 0.31 |

| White | 622 | 90.2 | 300 | 87.2 | 61 | 85.4 | 0.6 | 0.2–1.9 | 0.41 | 0.9 | 0.3–2.6 | 0.79 |

| Black | 49 | 6.3 | 32 | 8.2 | 7 | 11.3 | 1.9 | 0.5–7.3 | 0.36 | 1.4 | 0.4–5.8 | 0.62 |

| Indian | 249 | 3.5 | 87 | 4.6 | 13 | 3.3 | 1.0 | 0.5–1.9 | 0.88 | 0.7 | 0.3–1.5 | 0.35 |

| Impoverished families | 385 | 28.6 | 230 | 50.2 | 46 | 63.1 | 4.3 | 2.0–9.3 | <0.001 | 1.7 | 0.8–3.8 | 0.20 |

| Single parent | 329 | 31.1 | 205 | 47.4 | 42 | 56.5 | 2.9 | 1.3–6.3 | 0.01 | 1.4 | 0.6–3.3 | 0.39 |

Childhood DMDD and Adult Diagnostic Outcomes

| Psychiatric Diagnosis | Noncase Comparison Subjects | Psychiatric Comparison Subjects | DMDD Case Subjects | DMDD Case Subjects and Noncase Comparison Subjects | DMDD Case Subjects and Psychiatric Comparison Subjects | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p | |

| Any | 207 | 24.6 | 156 | 49.2 | 33 | 56.6 | 4.0 | 1.8–9.0 | <0.001 | 1.4 | 0.6–3.2 | 0.49 |

| Depressive | 43 | 4.3 | 35 | 6.7 | 9 | 24.9 | 7.4 | 2.3–23.3 | <0.001 | 4.6 | 1.4–14.9 | 0.01 |

| Anxiety | 55 | 7.4 | 62 | 20.7 | 18 | 45.4 | 10.4 | 4.2–26.0 | <0.001 | 3.2 | 1.3–8.1 | 0.02 |

| ASPD | 9 | 1.9 | 12 | 3.2 | 2 | 1.7 | 0.9 | 0.2–4.7 | 0.87 | 0.5 | 0.1–3.0 | 0.46 |

| Alcohol | 124 | 14.9 | 83 | 25.2 | 18 | 19.7 | 1.4 | 0.5–3.7 | 0.50 | 0.7 | 0.3–2.0 | 0.54 |

| THC | 114 | 14.1 | 75 | 21.1 | 22 | 29.5 | 2.6 | 1.0–6.4 | 0.05 | 1.6 | 0.6–4.1 | 0.37 |

| ≥2 disorders | 39 | 5.2 | 43 | 8.8 | 16 | 36.1 | 10.3 | 3.8–28.4 | <0.001 | 5.9 | 2.1–16.6 | <0.001 |

Childhood DMDD and Adult Functional Outcomes

Health functioning and risky or illegal behaviors.

| Characteristic | Noncase Comparison Subjects | Psychiatric Comparison Subjects | DMDD Case Subjects | DMDD Case Subjects and Noncase Comparison Subjects | DMDD Case Subjects and Psychiatric Comparison Subjects | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p | |

| Health Outcomes | ||||||||||||

| Serious illness | 38 | 5.6 | 26 | 7.0 | 3 | 1.3 | 0.2 | 0.1–0.9 | 0.04 | 0.2 | 0.0–0.8 | 0.03 |

| Serious accident | 99 | 13.8 | 51 | 10.8 | 15 | 15.2 | 1.1 | 0.4–3.0 | 0.82 | 1.5 | 0.5–4.3 | 0.46 |

| Sexually transmitted disease | 29 | 4.5 | 27 | 4.4 | 13 | 21.9 | 5.9 | 1.9–18.1 | 0.002 | 6.0 | 1.9–19.7 | 0.003 |

| Obesity | 308 | 25.2 | 150 | 35.7 | 30 | 28.2 | 1.2 | 0.5–2.6 | 0.71 | 0.7 | 0.3–1.7 | 0.43 |

| Any nonsubstance psychiatric disorder | 128 | 15.9 | 108 | 33.0 | 30 | 54.1 | 6.2 | 2.7–14.2 | <0.001 | 2.4 | 1.0–5.7 | 0.04 |

| Regular smoking (>1 day) | 377 | 37.1 | 224 | 57.7 | 49 | 75.0 | 5.1 | 2.2–11.8 | <0.001 | 2.2 | 0.9–5.4 | 0.08 |

| Self-report of poor health | 129 | 15.7 | 83 | 26.5 | 16 | 37.6 | 3.2 | 1.3–8.1 | 0.01 | 1.7 | 0.6–4.4 | 0.30 |

| Self-report of illness contagion | 206 | 21.7 | 110 | 34.5 | 25 | 45.0 | 3.0 | 1.3–6.9 | 0.01 | 1.6 | 0.6–3.8 | 0.34 |

| Self-report of slow illness recovery | 50 | 6.3 | 40 | 14.7 | 11 | 15.3 | 2.7 | 0.8–8.7 | 0.10 | 1.0 | 0.3–3.6 | 0.95 |

| Risky/Illegal Behaviors | ||||||||||||

| Official felony charge | 59 | 6.1 | 63 | 11.3 | 11 | 20.3 | 4.0 | 1.3–12.1 | 0.02 | 2.0 | 0.7–6.1 | 0.23 |

| Police contact | 52 | 9.5 | 54 | 18.4 | 20 | 30.5 | 5.9 | 2.1–16.5 | 0.001 | 3.7 | 1.4–10.3 | 0.01 |

| Lying | 30 | 3.6 | 26 | 6.4 | 2 | 1.7 | 0.5 | 0.1–2.2 | 0.32 | 0.3 | 0.1–1.2 | 0.09 |

| Physical fighting | 99 | 5.9 | 69 | 8.9 | 16 | 26.8 | 4.2 | 1.5–11.5 | 0.005 | 2.0 | 0.7–5.6 | 0.21 |

| Breaking in | 26 | 1.7 | 34 | 11.2 | 7 | 18.9 | 13.7 | 3.6–52.2 | <0.001 | 1.8 | 0.5–6.9 | 0.37 |

| Driving when impaired | 52 | 6.8 | 44 | 14.2 | 10 | 13.2 | 2.1 | 0.6–7.6 | 0.27 | 0.9 | 0.2–3.5 | 0.90 |

| Marijuana use | 241 | 28.8 | 157 | 44.6 | 28 | 39.0 | 1.6 | 0.7–3.7 | 0.29 | 0.8 | 0.3–1.9 | 0.61 |

| Other illicit drug use | 79 | 8.1 | 64 | 15.9 | 13 | 9.0 | 1.1 | 0.5–2.6 | 0.76 | 0.5 | 0.2–1.2 | 0.14 |

| Hooking up with a stranger | 77 | 12.9 | 59 | 18.3 | 14 | 16.3 | 1.3 | 0.5–3.9 | 0.61 | 0.9 | 0.3–2.7 | 0.81 |

Financial, educational, and social outcomes.

| Noncase Comparison Subjects | Psychiatric Comparison Subjects | DMDD Case Subjects | DMDD Case Subjects and Noncase Comparison Subjects | DMDD Case Subjects and Psychiatric Comparison Subjects | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | N | % | N | % | N | % | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p |

| Financial/educational functioning | ||||||||||||

| Impoverished | 521 | 56.9 | 255 | 68.0 | 57 | 86.3 | 4.8 | 2.4–9.5 | <0.001 | 3.0 | 1.4–6.3 | 0.005 |

| No high school diploma | 226 | 18.5 | 127 | 22.9 | 30 | 40.9 | 3.0 | 1.3–6.9 | 0.008 | 2.3 | 1.0–5.5 | 0.05 |

| No college | 482 | 42.4 | 278 | 62.4 | 64 | 82.3 | 6.3 | 2.5–16.2 | <0.001 | 2.8 | 1.1–7.5 | 0.04 |

| Dismissed from a job | 205 | 21.1 | 150 | 39.3 | 43 | 37.7 | 2.3 | 1.0–4.9 | 0.04 | 0.9 | 0.4–2.1 | 0.87 |

| Quit multiple jobs | 94 | 10.7 | 93 | 25.0 | 28 | 27.8 | 3.2 | 1.4–7.5 | 0.007 | 1.2 | 0.5–2.8 | 0.74 |

| Failing to honor financial obligations | 78 | 10.3 | 66 | 22.7 | 11 | 8.5 | 0.8 | 0.4–1.8 | 0.62 | 0.3 | 0.1–0.8 | 0.009 |

| Poor financial management | 77 | 7.7 | 53 | 17.0 | 13 | 10.2 | 1.4 | 0.6–3.0 | 0.46 | 0.56 | 0.2–1.3 | 0.18 |

| Social functioning | ||||||||||||

| Violent relationships | 41 | 3.2 | 46 | 10.0 | 11 | 15.0 | 5.4 | 1.6–18.8 | 0.007 | 1.6 | 0.5–5.5 | 0.45 |

| Poor relationship with parents | 111 | 16.1 | 89 | 30.2 | 20 | 37.2 | 3.1 | 1.1–8.5 | 0.03 | 1.4 | 0.5–3.9 | 0.55 |

| No best friend/confidante | 251 | 21.7 | 143 | 36.6 | 32 | 41.1 | 2.5 | 1.1–5.8 | 0.03 | 1.2 | 0.5–2.9 | 0.68 |

| Problems making/keeping friends | 31 | 3.8 | 28 | 9.8 | 10 | 7.6 | 2.1 | 0.8–5.4 | 0.13 | 0.8 | 0.3–2.1 | 0.59 |

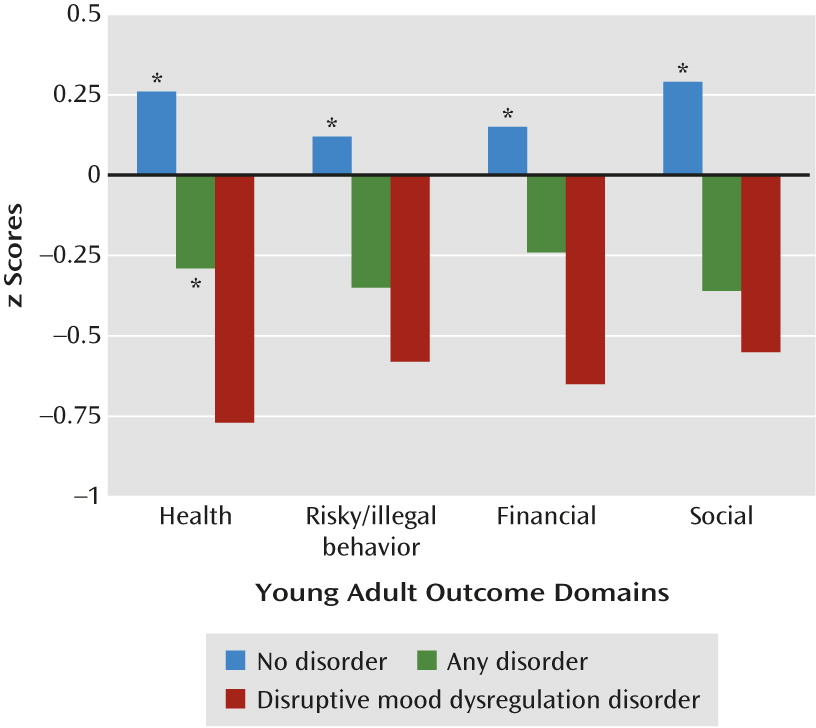

Comparisons across summary functional outcome scales.

Discussion

Conclusions

Supplementary Material

- View/Download

- 80.74 KB

References

Information & Authors

Information

Published In

History

Authors

Funding Information

Metrics & Citations

Metrics

Citations

Export Citations

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download.

For more information or tips please see 'Downloading to a citation manager' in the Help menu.

View Options

View options

PDF/EPUB

View PDF/EPUBLogin options

Already a subscriber? Access your subscription through your login credentials or your institution for full access to this article.

Personal login Institutional Login Open Athens loginNot a subscriber?

PsychiatryOnline subscription options offer access to the DSM-5-TR® library, books, journals, CME, and patient resources. This all-in-one virtual library provides psychiatrists and mental health professionals with key resources for diagnosis, treatment, research, and professional development.

Need more help? PsychiatryOnline Customer Service may be reached by emailing [email protected] or by calling 800-368-5777 (in the U.S.) or 703-907-7322 (outside the U.S.).