Half to two-thirds of patients with bipolar disorder have their first mood episode before age 18 (

1,

2), and pediatric bipolar disorder is highly recurrent. In a longitudinal follow-up of 115 preadolescents with manic or mixed episodes, 73.3% had recurrences over 8 years (

3). Early-onset bipolar illness is associated with a high risk of suicide and considerable psychosocial impairment (

3–

6).

There is increasing evidence in adult and child samples that bipolar depressive and manic symptoms can be alleviated by a combination of pharmacotherapy and psychosocial intervention (

7–

13). In a 2-year randomized trial (

11), we reported that adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders who received pharmacotherapy and 9 months of family-focused treatment (psychoeducation, communication training, and problem-solving skills training) had more rapid recoveries from depressive symptoms, more time in remission, and less severe depressive symptoms compared with those who received pharmacotherapy and enhanced care (three sessions of family education). Limitations of the trial included a small sample (N=58), inclusion of patients with subthreshold bipolar disorder, and lack of standardization of pharmacotherapy regimens.

The purpose of the present study was to examine the efficacy of family-focused treatment combined with best-practice pharmacotherapy in improving the symptomatic course of bipolar disorder in adolescents. We made several adjustments to the design of our first trial. First, we examined a larger cohort (N=145) of adolescents with bipolar I or II disorder recruited shortly after a manic, hypomanic, depressive, or mixed episode, and we excluded patients with subthreshold bipolar disorder. Second, study physicians implemented a standardized medication protocol supervised by expert pharmacologists. We hypothesized that adolescents receiving pharmacotherapy and family-focused therapy would have a more rapid recovery from an affective episode at study intake (the primary outcome measure), a longer time to recurrence, and less severe mood symptoms over 2 years when compared with adolescents receiving pharmacotherapy and enhanced care.

In two randomized studies of adult patients (

12,

13), we observed that benefits from family-focused treatment were most apparent after patients had completed 9 months of active treatment. In the present study, we explored the secondary hypothesis that patients in family-focused treatment would spend less time ill and more time in remission during the year following active treatment than patients in enhanced care.

Results

Participants

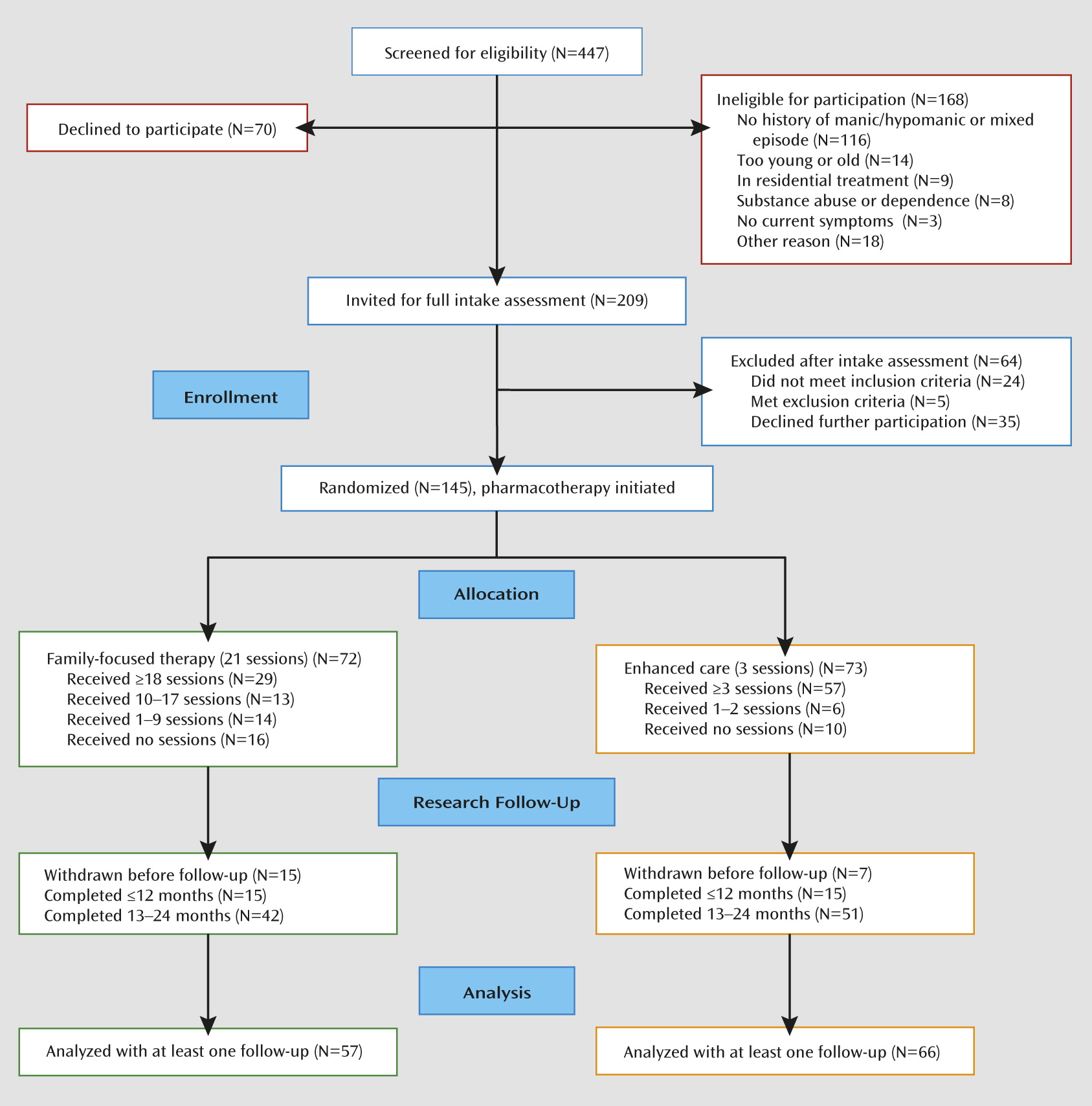

Participants were 145 adolescents with bipolar I disorder (N=77) or bipolar II disorder (N=68) (mean age, 15.6 years, SD=1.4). A total of 37 patients (25.5%) entered in a bipolar I or II depressed episode, 72 (49.7%) in a manic or hypomanic episode, and 36 (24.8%) in a mixed or subthreshold mixed (e.g., hypomanic for ≥1 week and depressed for <2 weeks) episode. None of the participants met the DSM-IV-TR course specifier for rapid cycling. The 72 participants in family-focused treatment did not differ significantly from the 73 in enhanced care on any of the variables listed in

Table 1. The 145 participants did not differ significantly in sex, age, or race/ethnicity from the 168 screened individuals who were ineligible for the study (

Figure 1). (Site differences are explored in the online

data supplement.)

Attrition

Of the 145 participants, 123 (84.8%) had at least one follow-up interview. This proportion did not vary significantly across treatment condition, site, sex, bipolar subtype, or index episode polarity. However, participants who terminated early had higher baseline K-SADS Mania Rating Scale scores than those who were followed for 2 years (F=5.57, df=1, 143, p=0.02). Participants who lived with both biological parents stayed in the study longer (mean=92.2 weeks, SD=28.3) than those who lived with one biological parent or in another living situation (mean=77.0 weeks, SD=35.9) (F=6.07, df=1, 121, p=0.02). Study site, living situation, baseline K-SADS Mania and Depression Rating Scale scores, and number of weeks of follow-up were included as covariates in the statistical models.

Psychosocial Treatment, Recovery, and Recurrence

During the 2-year study, 87 of the 123 (70.7%) patients for whom follow-up data were available met the 8-week recovery criteria from the index episode; the Kaplan-Meier estimate of cumulative probability of recovery was 87.1% (median time to recovery, 38 weeks, 95% CI=33–46). The 2-year Kaplan-Meier estimate of recovery in family-focused treatment was 85.2% (median time to recovery, 41 weeks, 95% CI=26–54) and in enhanced care, 88.7% (median=36 weeks, 95% CI=25–48; hazard ratio=1.21). In a Cox model that included all covariates, higher baseline K-SADS Depression Rating Scale scores (χ

2=11.37, df=1, p<0.001) and lower Mania Rating Scale scores (χ

2=6.63, df=1, p=0.01) were associated with longer time to recovery; the two treatment arms, however, did not differ in recovery time. (See the online

data supplement for survival analyses using a briefer period [≥4 weeks] to define recovery.)

The family-focused treatment and enhanced care groups also did not differ in weeks to recovery from baseline depressive symptoms or from baseline manic/hypomanic symptoms. Furthermore, there was no interaction between treatment group and baseline illness polarity in any time-to-event analysis. Within the mixed (N=36) subgroup, the median time to recovery from the index episode was 42 weeks (95% CI not calculable) for patients in family-focused treatment and 40 weeks (95% CI=23–62) for patients in enhanced care, a nonsignificant difference.

Among the 87 patients who recovered, 50 (57.5%) had a recurrence during the 2-year study. The Kaplan-Meier estimate of cumulative probability of recurrence was 65.1%, with a median time to recurrence of 37 weeks (95% CI=18–55). Of the 50 participants with recurrences, eight had manic, 11 had hypomanic, three had mixed, and 28 had depressive recurrences. Of 39 participants in family-focused treatment who recovered, 25 had recurrences (Kaplan-Meier probability estimate, 74.4%; median time to recurrence, 27 weeks, 95% CI=16–55). Of 48 in enhanced care who recovered, 25 had recurrences (Kaplan-Meier estimate, 58.8%; median time to recurrence, 37 weeks, 95% CI not calculable). In a Cox model that included all demographic and baseline illness scores as covariates, treatment condition was not associated with time to any recurrence, time to depression recurrence, or time to manic or hypomanic recurrence.

Adolescents who lived with both biological parents had a longer time to manic recurrence than those living in another arrangement (χ2= 3.69, df=1, p=0.05). There were no interactions of treatment group, site, and living situation on time to recovery or recurrence.

Number of Treatment Sessions

Across sites, patients in family-focused treatment attended a mean of 15.4 (SD=7.3) of 21 expected protocol therapy sessions and a mean of 2.0 (SD=5.5) extra (nonprotocol) sessions. In enhanced care, patients attended a mean of 2.5 (SD=1.1) of three expected protocol sessions and 0.8 (SD=2.3) nonprotocol sessions. The number of nonprotocol sessions did not differ across treatment conditions or sites. Inclusion of a therapy contact ratio (number of psychosocial contacts to number of expected sessions in each treatment) in the survival models did not alter the null effects of treatment condition on time to recovery or recurrence.

Longitudinal Trajectory of Mood Symptoms

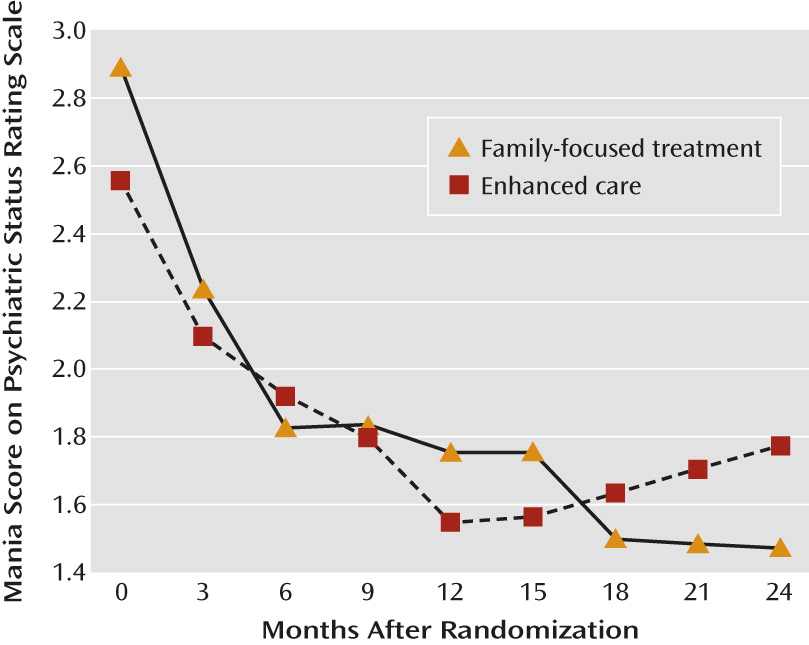

There were no treatment group differences in the percentage of weeks free of mood symptoms (Psychiatric Status Rating Scale scores ≤2) or the percentage of weeks with acute mood symptoms (Psychiatric Status Rating Scale scores ≥5) across study years 1 and 2 (

Table 2). There were also no main effects of treatment group or treatment group-by-time (year 1, year 2) interactions on percentage of weeks with depressive symptoms. However, adolescents in family-focused therapy showed a greater increase from year 1 to year 2 in proportion of weeks without mania/hypomania symptoms compared with those in enhanced care (F=4.02, df=1, 87, p=0.048).

Patients in family-focused treatment did not differ in mean Psychiatric Status Rating Scale scores for depression across the 3-month study epochs. However, patients in family-focused treatment showed greater improvements in mean Psychiatric Status Rating Scale scores for mania/hypomania across 3-month intervals than did patients in enhanced care (F=1.98, df=8, 742, p=0.046) (

Figure 2). This treatment-by-time interaction remained significant when covarying site, baseline K-SADS Mania Rating Scale score, and living situation. There was no treatment-by-baseline K-SADS Mania Rating Scale score interaction on Psychiatric Status Rating Scale scores across the 3-month epochs, and there were no treatment effects or treatment-by-time interactions on K-SADS Depression or Mania Rating Scale scores across the study epochs.

Effects of Comorbid Disorders

Patients with comorbid anxiety disorders (N=57;

Table 1) had earlier mood recurrences (median=19 weeks, 95% CI=13–42) than patients without anxiety disorders (median=67 weeks, 95% CI not calculable) (χ

2=6.62, df=1, p=0.01). Patients with comorbid attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (N=48) had earlier mood recurrences (median=17 weeks, 95% CI=11–25) than patients without ADHD (N=97; median=53 weeks, 95% CI not calculable) (χ

2=4.39, df=1, p=0.04). In a Cox model that included treatment group, site, living situation, and baseline symptom scores, only concurrent anxiety disorders remained strongly associated with time to mood recurrence (χ

2=7.65, df=1, p=0.006).

Pharmacotherapy Regimens

The number of pharmacotherapy visits during the trial (mean=11.6, SD=6.9) did not differ between treatment groups and did not predict time to recovery or recurrence. Participants in the two groups did not differ in the mean number of medications prescribed at baseline (family-focused treatment: mean=2.0, SD=1.0; enhanced care: mean=1.6, SD=0.9) or at the 12-month or 24-month follow-ups (

Table 3). The two groups also did not differ in the likelihood of taking lithium (compared with other mood stabilizers), second-generation antipsychotics (considered individually or as a class), or adjunctive antidepressants, psychostimulants, or anxiolytics at any point in the trial, or in having a mood stabilizer or antidepressant added or discontinued (

Table 3). When dichotomous variables indicating the presence or absence of each class of medications were included in Cox survival models, no effects emerged for psychosocial treatments on time to recovery or recurrence.

Discussion

In five controlled trials involving adult patients with bipolar I or II disorder (

8,

12,

13,

25,

26), family-focused treatment was associated with more rapid recovery from depressive episodes, longer intervals to recurrences, and less severe mood symptoms over 1–2 years than pharmacotherapy and brief psychoeducation (enhanced care) or active clinical management. Unlike in our previous randomized trial of adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders (

11), we observed no differences in adolescents with bipolar I or II disorder between family-focused treatment and enhanced care on time to recovery or severity of mood symptoms over 2 years.

The comparable efficacy of the two treatments did not appear to be due to unique characteristics of this study’s population. The 2-year rates of recovery (87%) and recurrence (57.5%) were comparable to the rates observed in the Course and Outcome of Bipolar Youth Study (81.4% and 62.5%, respectively over a mean of 123.7 weeks) (

4) and the Geller et al. follow-up study of prepubertal and early adolescents with mania (65% and 55% over 2 years) (

27). Compared with the participants in our first adolescent trial, however, those in the present study were more likely to have bipolar II disorder (47% compared with 10%), manic or mixed episodes at intake (65% compared with 26%), and comorbid anxiety disorders (33.1% compared with 3.5%). Although baseline depression severity and comorbid anxiety disorders were independently associated with time to recovery and recurrence, respectively, they did not moderate the efficacy of psychosocial treatments.

There were important design differences between the two trials that may partially explain the different results. In the present study, participants in the three-session enhanced care condition received at least monthly sessions of medication management from study psychiatrists, regular clinical monitoring by an independent evaluator, and booster sessions as needed for 2 years. Enhanced care psychoeducation sessions were closely monitored by supervisors to ensure that fidelity to the clinician manuals was equivalent across sites and conditions. Thus, enhanced care was more regulated than in our first trial and may have been more effective as a result.

Similarly, oversight of pharmacological management was more intensive in this study than in our first study. When the first trial was initiated, there were no published pharmacotherapy guidelines for pediatric bipolar disorder. In the present study, pharmacologists were supervised by experts in the implementation of standardized treatment guidelines (

28) and rated for guideline adherence. It is possible that the quality of pharmacotherapy in this trial limited the degree to which the effects of psychotherapy could be observed over and above medication effects.

A secondary analysis revealed that family-focused treatment was associated with lower mania severity ratings during year 2 of the study and with greater increases from year 1 (active intervention period) to year 2 (follow-up) in the proportion of weeks without mania symptoms. Two previous trials found that differences in outcome between family-focused treatment and comparison conditions became statistically significant only during a posttreatment follow-up (

12,

13). The emphasis in family-focused treatment on early recognition of mood changes (see the Patient Perspective) and communication and problem-solving skills may not translate into clinical benefits for patients until families have implemented these strategies during new cycles of illness.

Comparing results of the present trial to those from adult samples raises the question of whether family-focused treatment is developmentally attuned to the needs of adolescents. The emphasis on family relationships may neglect the role of peer and romantic relationships in symptom exacerbation. Adolescents respond with greater emotional intensity to evaluative scrutiny from peers than do children or adults (

29). We found in previous work (

30) that adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders who reported higher levels of stress in peer or romantic relationships showed less improvement in family treatment over 12 months. The overall effects of family intervention on the course of adolescent bipolar disorder may be enhanced by a greater focus on skills for managing peer aggression, peer rejection, and relationship stress.

Two secondary findings merit discussion. First, consistent with naturalistic studies of children and adolescents (

4) and of adults (

31–

35), the polarity of the index episode was strongly associated with more severe symptoms of the same polarity at follow-up. As found in adult treatment trials (

36), more severe depressive symptoms at intake were associated with longer time to recovery. Thus, in both adults and adolescents with bipolar disorder, fully stabilizing the current episode is an important consideration for effective prophylaxis.

Second, adolescents who lived with both biological parents had a longer time to manic recurrence than those living with one biological parent. An association between having an intact biological family and shorter time to recovery has been observed in children and adolescents with mania (

37). It is not clear whether the effects of family structure on outcome can be attributed to genetic factors (i.e., higher genetic load in divorced pairs), stress attributable to custody arrangements or financial difficulties, prior traumatic experiences (e.g., domestic violence;

38), or differences in medication compliance or access to treatment. Nonetheless, clinicians may need to take a more active role in monitoring treatment consistency and response in youths with mood disorders in single-parent families.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Adrine Biuckians, Jedediah Bopp, Victoria Cosgrove, L. Miriam Dickinson, Dana Elkun, Jessica Lunsford, Chris Hawkey, Zachary Millman, Aimee Sullivan, and Marianne Wamboldt of the University of Colorado for their assistance.