Because of the wide accessibility of twin samples (

1), psychiatric genetic epidemiology has, over recent decades, focused on clarifying the contributions of genetic and environmental factors to the familial aggregation of disorders within generations. Adoption designs, the primary approach to delineating sources of transmission

across generations, are more difficult to implement. After a series of influential adoption studies in schizophrenia and alcoholism from the 1960s through the 1980s (e.g.,

2–

5), this method has since been less frequently utilized (with some noteworthy exceptions, e.g.,

6,

7). While adoption designs are elegant, they are becoming rarer, and most adoption samples have several methodological limitations, including nonrandom placement of adoptees, missing information on many biological fathers, and unrepresentative adoptive parents (

8).

Method

As outlined previously for drug abuse (

16), alcohol use disorders (

17), and criminal behavior (

18), we used linked data from multiple Swedish nationwide registries and health care data. Linking was achieved via the unique individual 10-digit personal identification number assigned at birth or immigration to all Swedish residents. To preserve confidentiality, this identification number was replaced by a serial number. The following sources were used in our database: the Total Population Register, containing annual data on family and geographical status; the Multi-Generation Register, providing information on family relationships; the Swedish Hospital Discharge Register, containing all hospitalizations for all Swedish inhabitants from 1964 through 2010; the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register, containing all prescriptions in Sweden picked up by patients from 2005 through 2010; the Outpatient Care Register, containing information from all outpatient clinics from 2001 through 2010; the Primary Health Care Register, containing outpatient diagnoses from 2001 through 2007 for 1 million patients from Stockholm and middle Sweden; the Swedish Crime Register, containing national data on all convictions from 1973 through 2011; the Swedish Suspicion Register, containing national data on all individuals strongly suspected of crime from 1998 through 2011; the Swedish Mortality Register, containing all causes of death; and the Population and Housing Censuses, which provided information on household and geographical status in 1960, 1965, 1970, 1975, 1980, and 1985. We secured ethical approval for this study from the Regional Ethical Review Board of Lund University.

Drug abuse was identified in the Swedish medical and mortality registries by ICD codes (ICD-8: drug dependence [304]; ICD-9: drug-induced psychoses [292] and drug dependence [304]; ICD-10: mental and behavioral disorders due to psychoactive substance use [F10–F19], except those due to alcohol [F10] or tobacco [F17]); in the Suspicion Register, which records arrests by codes 3070 (driving under the influence of drugs), 5010 (drug possession), 5011 (drug use), and 5012 (possession and use), which reflect crimes related to drug abuse; and in the Crime Register, which reflects convictions by references to laws covering narcotics (law 1968:64, paragraph 1, point 6) and drug-related driving offenses (law 1951:649, paragraph 4, subsection 2 and paragraph 4A, subsection 2). Drug abuse was identified in individuals (excluding cancer patients) in the Prescribed Drug Register who had filled prescriptions of hypnotics and sedatives (Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical [ATC] Classification System N05C and N05BA) or opioids (ATC: N02A) in dosages consistent with drug abuse, that is, on average more than four defined daily doses a day for 12 months.

Criminal behavior was identified by registration in the Swedish Crime register, which excluded convictions for minor crimes like traffic infractions. Otherwise, our measure of criminal behavior utilized all available criminal conviction types.

Alcohol use disorders were identified in the Swedish medical and mortality registries by ICD codes (ICD-9 codes V79B, 305A, 357F, 571A-D, 425F, 535D, 291, 303, 980; ICD-10 codes E244, G312, G621, G721, I426, K292, K70, K852, K860, O354, T51, F10); in the Crime Register by codes 3005, 3201, which reflect crimes related to alcohol abuse; in the Suspicion Register by codes 0004 and 0005 (only those individuals with at least two alcohol-related crimes or suspicion of crimes from both the Crime Register and the Suspicion Register were included); and in the Prescribed Drug Register by prescriptions for disulfiram (ATC: N07BB01), acamprosate (N07BB03), or naltrexone (N07BB04).

Sample

Among all individuals born in Sweden between 1960 and 1990 (N=3,257,987), we selected those who, from ages 0 though 15, resided all 15 years in the same household as their mother, never resided in the same household or small geographical area (see below) as their biological father, and resided for ≥10 years in the same household as their stepfather (N=41,360, 1.26%).

Household was ascertained as follows: From 1960 to 1985 (every fifth year), we used the household identification number from the Population and Housing Census. The household identification number includes all individuals living in the same dwelling. For the years we did not have data, we approximated the household identification number with the available information from the year closest in time. From 1986 onward (every year), we used the family identification number from the Total Population Register. Family identification numbers are assigned to individuals who are related or married and who are registered as residing at the same property (each individual can be part of only one family). In addition, adults who are registered at the same property and have children together but are not married are registered as being in the same family.

Geographical status was defined in terms of Small Areas for Market Statistics (SAMS), which are small geographical units defined by Statistics Sweden, the Swedish government statistics bureau. There are approximately 9,200 SAMS throughout Sweden, with an average population of around 1,000. From 1960 to 1970, we had no information on SAMS areas, and therefore we used parishes as a proxy for SAMS for these years. The parishes serve as districts for the Swedish census and elections and have approximately the same number of inhabitants as SAMS areas. From 1960 to 1985, we only had information for every fifth year, and for that reason we approximated the geographical status with the information from the year closest in time.

A stepfather was defined as a man 18 to 50 years older than the offspring, living in the same household as the offspring, and not related to the offspring as an uncle, grandfather, cousin, brother, or half-brother. From 1986 onward, for an offspring living with his or her mother, we capture the stepfather only if he is married to the offspring’s mother or had a child together with that mother. Forty-five percent of our sample was born between 1960 and 1970, and 18% between 1980 and 1990. The not-lived-with status arose in only a small minority of cases (2.5%) through death of the father in the year of the child’s birth.

We used Cox proportional hazard models to investigate the future risk for drug abuse, alcohol use disorders, and criminal behavior in offspring as a function of presence of drug abuse, alcohol use disorders, and criminal behavior in the three types of parents (mother, not-lived-with father, and stepfather). Robust standard errors were used to adjust the 95% confidence intervals, as some full-sibling pairs (N=759) were included in the analysis. Follow-up time (in years) was measured from age 15 of the offspring until year of first registration for drug abuse, alcohol use disorders, or criminal behavior or until death, emigration, or end of follow-up (year 2011), whichever came first. In all models, we investigated the proportionality assumption. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.3 (

19).

Discussion

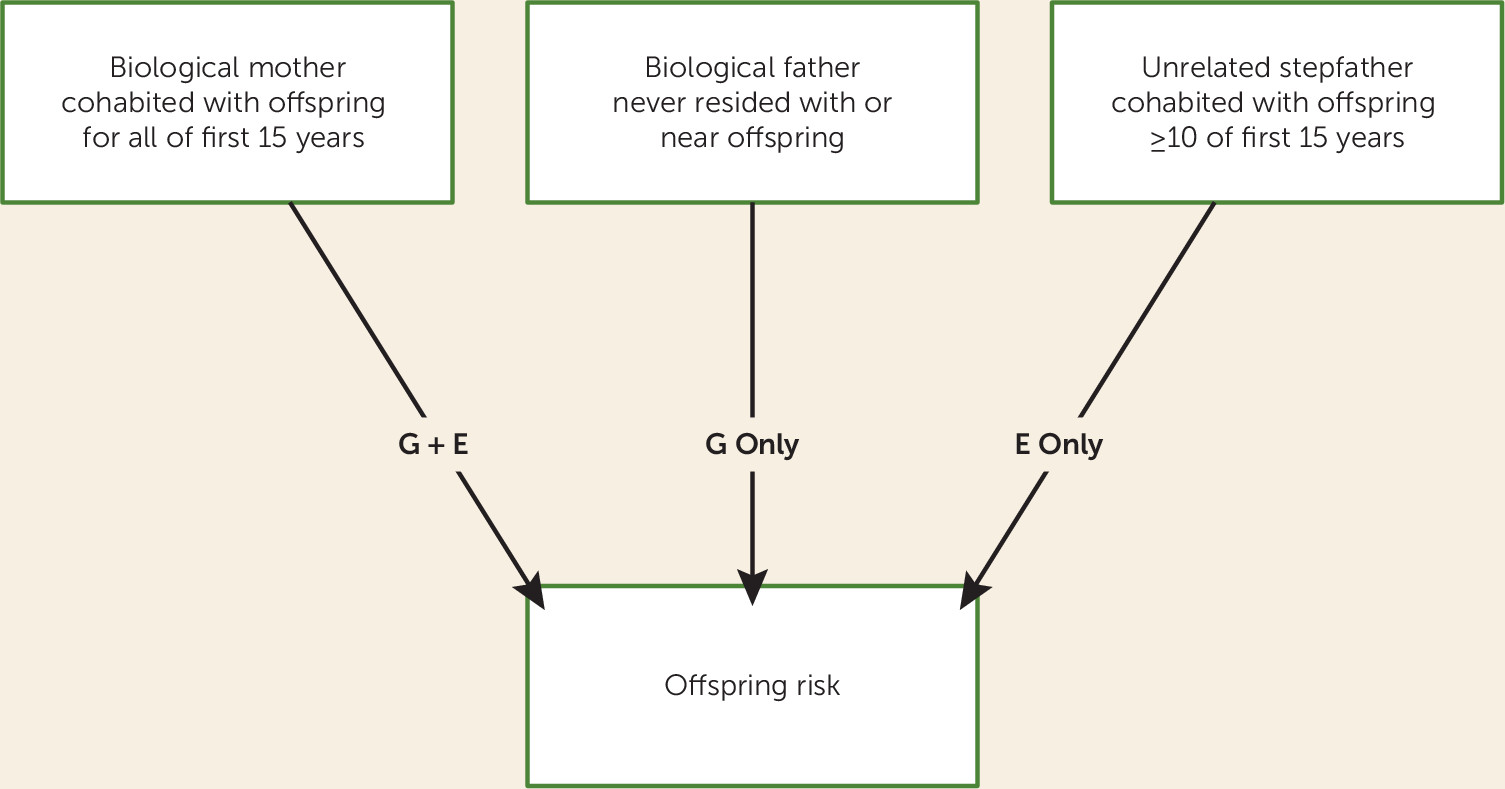

Our first goal in this study was to introduce the triparental design, which we see as having five major strengths. First, it is the only design that can compare within the same family the three paradigmatic kinds of parent-child relationships: a biological parent who raises the child (genes plus rearing), a not-lived-with biological parent who has limited contact with the child (genes only), and an unrelated stepparent who raises the child (rearing only). The not-lived-with parents and stepparents are analogous to the biological and adoptive parents in an adoption design.

A second advantage of this design is the relative frequency of triparental families. In Sweden, offspring from triparental families are more than twice as common as adoptees. Third, the legal and confidentiality concerns that surround adoptions and which outside of Scandinavia have substantially hindered adoption research do not apply to triparental families. Fourth, the triparental design could readily be analyzed by structural equation modeling to obtain quantitative estimates of genetic and environmental transmission on a liability scale rather than the epidemiological approach we took here, which utilized hazard ratios (

20).

Finally, an important methodological concern about the validity of adoption studies is the atypicality of adoptive parents (

8). In Sweden as elsewhere, they are selected for low rates of psychopathology and high levels of income and education (

21). The reduced level and variation of environmental adversity in adoptive homes might result in an underestimation of rearing effects. Compared with adoptive parents, stepfathers in triparental families are much more representative of the general population in Sweden with respect to their rates of drug abuse, alcohol use disorders, and criminal behavior (

Table 1). This should result in more generalizable estimates of the importance of rearing effects from triparental family studies than would be possible from adoption designs.

However, the triparental design has one noteworthy limitation: the only common triparental family configuration in Sweden includes a biological mother raising her own child, a not-lived-with father, and a stepfather. For the study period, we could identify only 2,151 triparental families with a biological father who raised the child plus a not-lived-with mother and a stepmother, a sample too small to yield estimates with adequate precision for our rare outcomes. Could our triparental design be biased by including only mothers who were both genetically and environmentally related to their children and only not-lived-with fathers and stepfathers? For example, if intrauterine effects were important, we would expect parent-offspring resemblance for externalizing syndromes to be stronger in both biological/rearing mothers and not-lived-with mothers than would be seen in fathers. Or, if females required a higher liability than males to express externalizing disorders, this would predict a higher risk for these syndromes in biological offspring of affected mothers than of affected fathers.

We were able to address these questions empirically.

Table 5 compares the association between drug abuse, alcohol use disorders, and criminal behavior in parents and offspring (

Table 5) in intact families and in not-lived-with parents and stepparents who were not part of our triparental family sample. Contrary to the pattern predicted for intrauterine effects or for a higher genetic liability in affected women than in affected men, of the six comparisons of biological parents, three were stronger from fathers and three from mothers. For biological/rearing parents from intact families, parent-offspring resemblances were very similar for alcohol use disorders and criminal behavior, and for drug abuse, they were modestly stronger for fathers. Our inclusion of only biological/rearing mothers in our triparental sample is unlikely to result in substantial biases. Furthermore, none of the comparisons of the strength of parent-offspring transmission were significantly different in not-lived-with mothers compared with fathers or in stepmothers compared with stepfathers. These results indicate that our findings from not-lived-with fathers and stepfathers in our triparental families are probably representative of not-lived-with parents and stepparents more generally.

Another limitation of the triparental family design is that the information needed to identify such families may not be available in many countries. However, there should be no legal barriers to studying them, as is often the case with adoptions.

The triparental family is not the only design outside of classical adoption and twin studies that can distinguish between “nature” and “nurture.” Studies of siblings and half-siblings can be useful, but like twin studies, they clarify sources of horizontal (or within-generation) transmission (

22). By contrast, samples of twins and their parents (

23) or of twins and their children (

24) can, like adoption and the triparental samples, elucidate the genetic and environmental contributions to vertical (or cross-generational) transmission (

25).

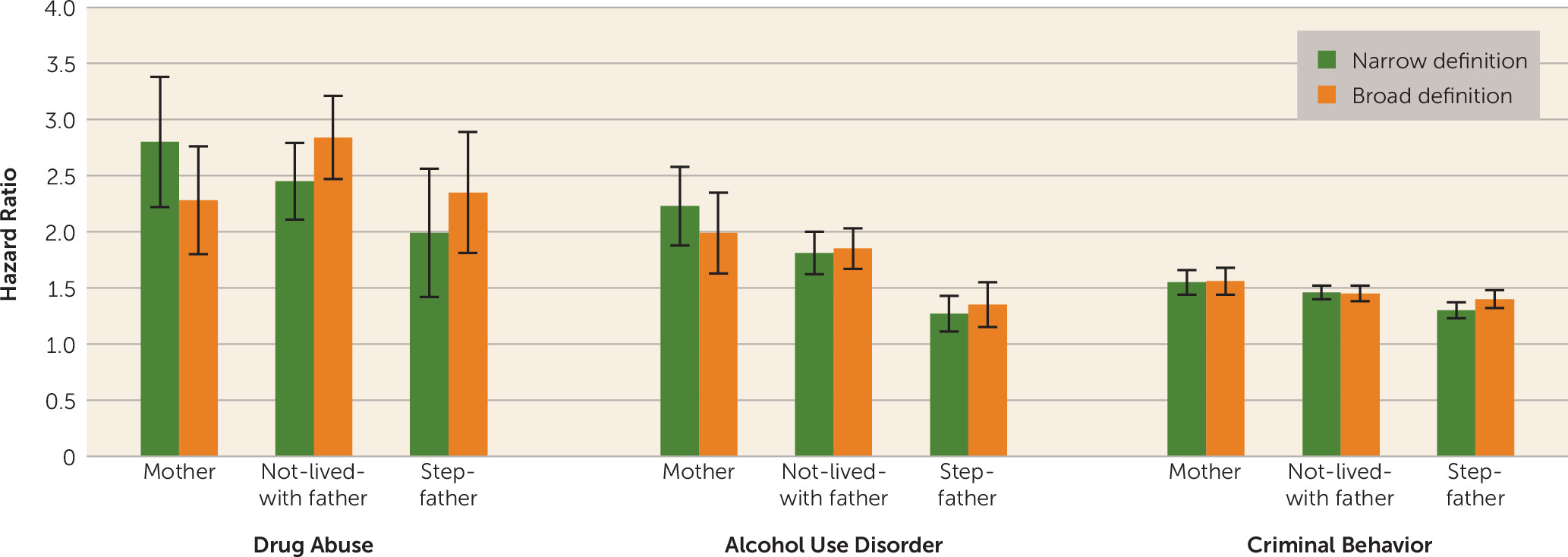

Our second goal in this study was to utilize the triparental family design to further clarify the nature of the cross-generational transmission of three paradigmatic externalizing syndromes: drug abuse, alcohol use disorders, and criminal behavior. We showed, as expected, that the risks for each of the externalizing syndromes were positively correlated among the three parental figures. Since our goal was to quantify the unique relationship between each parental type and the offspring, all of our statistical analyses controlled for these background correlations. As shown in the key analyses (

Table 3), offspring risk for each syndrome was strongly and significantly predicted by a history of that syndrome in the mother, in the not-lived-with father, and in the stepfather. For all three syndromes, the magnitude of the hazard ratios had the same order: mother > not-lived-with father > stepfather. However, these results do not exhaust the information contained in the triparental design; the role of genetic factors can also be inferred from the relative strength of the prediction of offspring risk from mothers (genes plus rearing) compared with stepfathers (rearing only). For all three syndromes, the hazard ratio from mothers is appreciably and significantly higher than that seen from stepfathers, thus providing independent evidence for the role of genetic factors in parent-offspring transmission. The importance of rearing effects can also be inferred from the relative strengths of risk prediction from mothers (genes plus rearing) compared with not-lived-with fathers (genes only). Here the differences are all in the expected direction but are modest and statistically significant only for alcohol use disorders, and approach significance for criminal behavior. In aggregate, our results provide strong and consistent support for the etiological importance of both genetic and environmental factors in the parent-to-offspring transmission of drug abuse, alcohol use disorders, and criminal behavior. They also suggest with similar consistency that genetic factors are more important than rearing-environmental factors in this transmission.

It is of particular interest to compare these results with our previous classical Swedish adoption studies of drug abuse, alcohol use disorders, and criminal behavior (

16–

18). Congruent with our present findings, risks for each of these three syndromes in adoptees were predicted by a history of the same syndrome in adoptive and in biological parents (

16–

18). All of these relationships were statistically significant except in adoptive parents of adoptees with drug abuse (

16). Furthermore, consistent with our findings, the association with adoptee outcomes was stronger in biological than in adoptive parents (

16–

18). Using two independent samples with entirely different designs, we have been able to replicate our key insights into the sources of the parent-offspring resemblance for drug abuse, alcohol use disorders, and criminal behavior.

We previously compared parent-offspring resemblance for drug abuse and criminal behavior in intact families and distinct families containing not-lived-with parents and stepparents (

26,

27). Our results were qualitatively similar to those obtained here with triparental families. The main limitation of this previous approach was the much higher rates of externalizing disorders in both the parents and offspring of the not-lived-with families and stepfamilies compared with the intact families. Thus, in sharp contrast to the triparental design, examining transmission of externalizing syndromes in such different family types was not comparing like with like.

Our third goal in this study was to explore the specificity of the cross-generational transmission of drug abuse, alcohol use disorders, and criminal behavior. Focusing on the not-lived-with fathers, where parent-offspring resemblance results only from genetic factors, we see clear evidence for nonspecificity in that each syndrome in not-lived-with fathers was associated with a significantly increased risk for all three syndromes in offspring (

Table 4). However, consistent with some specificity in transmission, for two of our three syndromes (alcohol use disorders and criminal behavior), the hazard ratios for within-syndrome parent-offspring transmission (i.e., alcohol use disorders → alcohol use disorders and criminal behavior → criminal behavior) were considerably stronger than for cross-syndrome transmissions. Examining stepparents, where parent-offspring resemblance results only from environmental processes, we see more evidence for nonspecificity of transmission. Having a stepfather with criminal behavior is associated with the greatest increased risk for drug abuse, alcohol use disorders, and criminal behavior.

Results from stepparents are particularly informative about the degree to which the environmental parent-offspring transmission for externalizing disorders is direct or indirect. Transmission would be direct if drug abuse, alcohol use disorders, and criminal behavior were primarily “taught” by parents to their children like language or religion, or learned by children from observing parental behaviors (

28–

31). Alternatively, externalizing disorders could be transmitted across generations indirectly. Parental drug abuse, alcohol use disorders, and criminal behavior often interfere with effective parenting, and they increase the risk for parental divorce, premature death, and lowered socioeconomic status, all of which can predispose offspring to externalizing disorders (

29,

32–

37). Our results are consistent with predominantly indirect parent-offspring environmental transmission for drug abuse and alcohol use disorders that are most strongly predicted by criminal behavior in the stepfather. By contrast, our findings support a mechanism of direct transmission for criminal behavior, as offspring criminal behavior was also most strongly predicted by criminal behavior in the stepfather.

Our definitions of stepfathers and not-lived-with fathers were made as narrow as feasibly possible. It was therefore of interest to examine a more broadly defined group of triparental families based on rearing biological mothers and not-lived-with fathers who resided with or near their offspring for less than 2 years and stepfathers who were present for 8–10 of the offspring’s first 15 years (N=33,987). In

Figure 2, we compare results from hazard ratio analyses in these “broadly” defined and our original “narrowly” defined triparental families. The results are very similar for alcohol use disorders and criminal behavior. For drug abuse, in the broadly defined compared with the narrowly defined triparental families, the hazard ratios are modestly greater for not-lived-with fathers and stepfathers and lower for biological mothers. These results provide further evidence for the validity of our findings and suggest that useful information is available about parent-offspring transmission in triparental families that are less narrowly defined than those primarily examined in this study.

Limitations

These results should be interpreted in the context of four potentially important methodological limitations. First, our data are from Sweden and may or may not extrapolate to other populations. Second, while ascertaining cases of drug abuse, alcohol use disorders, and criminal behavior from registry data has important advantages, especially independence from subject cooperation and accurate recall and reporting, it also has significant limitations. In Sweden as in most other countries, a majority of crimes are not officially reported or do not result in a conviction. Therefore, our measure of criminal behavior reflects the more severe end of the spectrum of criminal activities (

38). For drug abuse and alcohol use disorders, there are surely false negatives for individuals who abuse substances but avoid medical or police attention. However, the validity of our detection of these syndromes is supported by evidence for strong associations of cases detected from our different registries. The mean odds ratio for case detection of drug abuse across our five relevant registries was 52 (

16), and for alcohol use disorders across four registries, 33 (

17).

Third, we set 10 years as a minimum duration of cohabitation for stepparents and offspring because the sample sized declined precipitously with longer periods. Therefore, we were not able to match precisely for duration of rearing between mothers and stepfathers. This could result in an underestimate of the effects of environmental parent-offspring transmission. Finally, while we knew that the not-lived-with father never resided with or near his offspring, we had no information about other contacts. If they were extensive, that could strengthen the not-lived-with father’s effect and upwardly bias our estimates of genetic influences.