The limitations of the modern psychiatric diagnostic system embodied in DSM-IV and DSM-5 are well established (

1–

3). They include an inability to capture the dimensional nature of many disorders, a reliance on combining heterogeneous symptoms or presentations, and a high rate of symptom overlap that may result in patients being diagnosed with multiple disorders simultaneously. Of perhaps greater concern, these diagnostic categories appear to correspond poorly to the neurobiology of psychiatric illness; for example, data from recent large-scale genome-wide association studies indicate marked overlap in liability across five major psychiatric disorders (

4). Moreover, some symptom domains that are known to be important in multiple disorders, such as executive function, are simply not captured by DSM criteria (

5).

The RDoC were proposed to facilitate a broader and more integrative phenotypic assessment of neuropsychiatric disease, corresponding more directly to underlying neurobiology (

2,

6). The five symptoms domains—negative valence, positive valence, cognitive functioning, arousal, social processes—are described in the proceedings of workgroups convened by NIMH in 2011 and 2012 (

http://www.nimh.nih.gov/research-priorities/rdoc/index.shtml). The institutional emphasis on this new nosology has been made explicit, with the NIMH director stating, “We plan to use RDoC as a framework for guiding our funding” (

7).

This initiative poses two challenges for clinicians and clinical investigators in psychiatry. First, at present there is no consensus on the means of capturing these domains in clinical settings. Second, because these categories are constructed de novo to be independent of the DSM nosology, they effectively orphan decades of expertly collected clinical data. As a consequence, potentially powerful database studies of psychiatric illnesses or risk factors (

8,

9) made newly feasible by electronic health records (EHRs) cannot make use of RDoC-informed analysis.

In an effort to preserve the potential contribution of past experience as captured in EHRs to future RDoC-informed investigation, we applied natural language processing and information retrieval techniques to calculate estimates of RDoC domain loading from clinical narrative notes. To this end, we scored narrative clinical free text from a large New England health system according to the text’s similarity to documents collected by Internet searches on terms from the RDoC workgroup concept matrix. While this process represents only a starting point in translating between clinical and research measures, it provides evidence that clinicians do encode dimensional elements in their narrative notes that can be understood in the context of RDoC.

Method

Cohort and Outcome Derivation

We used the i2b2 server software, version 1.6.04 (

10), to access and manipulate demographic data, billing codes, and narrative notes from the EHRs of a large Boston-based hospital that includes a network of primary and specialty care settings.

The cohort examined here was composed of 2,484 narrative admission notes from 2,010 patients admitted to an adult psychiatric inpatient unit at an academic medical center between 2011 and 2013. No inclusion or exclusion criteria were applied; all patients were age 18 or older at time of admission.

Outcome measures were those that could be derived directly from coded data available in the EHR as an artifact of routine care. Length of hospital stay was determined from billing data. Time to all-cause hospital readmission was determined by examining the subsequent 2-year period to identify readmissions to the index hospital. (In Massachusetts, readmissions would typically occur at the same hospital, but because it is an “open” system, we cannot exclude the possibility of interim admissions elsewhere.)

Development and Application of Scoring Tool

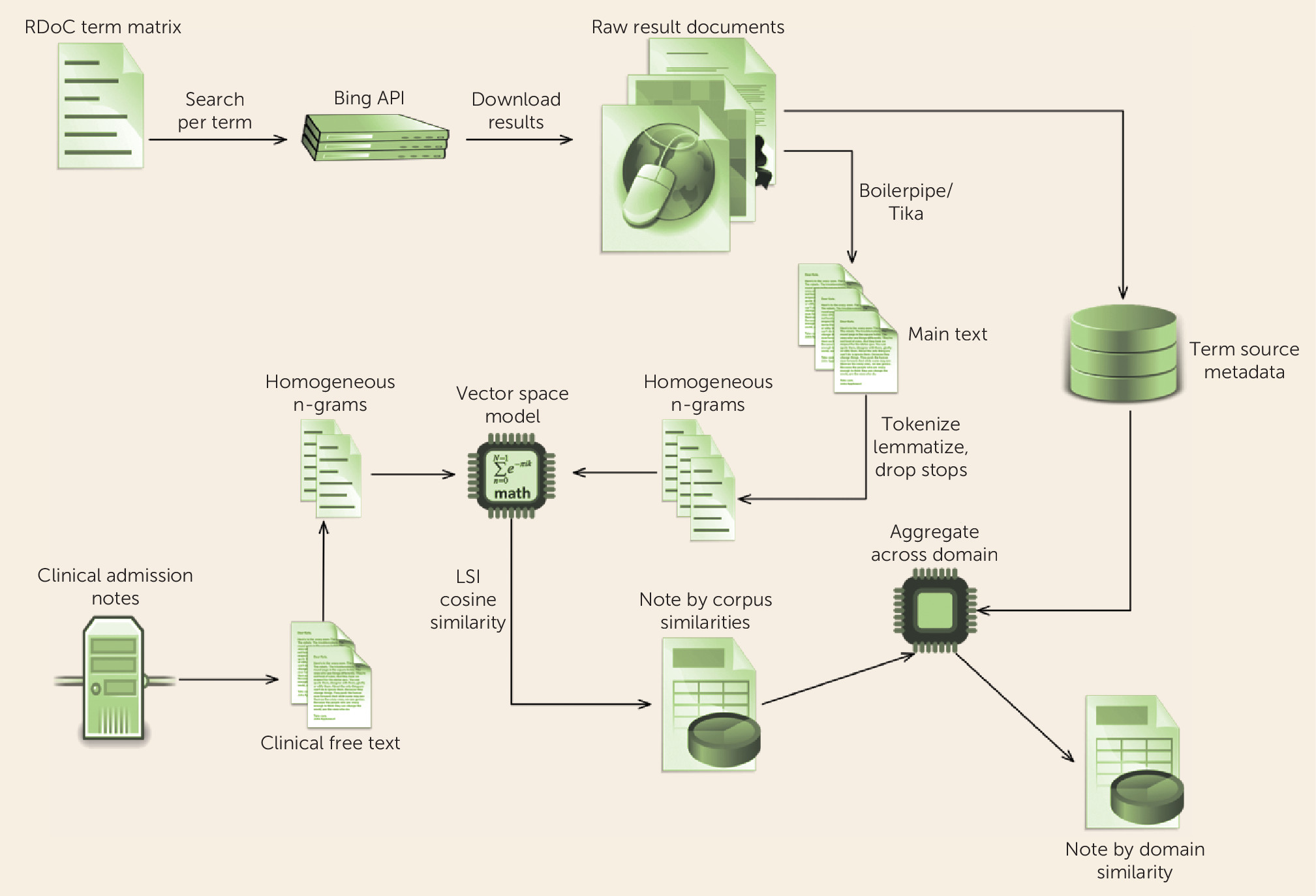

Methods for scoring individual notes are described in

Figure 1. In summary, we began with individual terms listed in the RDoC workgroup documents and identified synonyms or other relevant concepts using an automated web search. Each note was then scored according to its similarity to the body of documents identified by the search, yielding five estimated RDoC-like domains. Thus, higher levels of a given domain refer to greater loading for terms in that domain; while in general this would indicate greater severity (e.g., for negative valence), for the social domain in particular, this could correspond to greater social involvement (a strength) or more social activity (which would be a concern in mania), with similar effects in arousal.

We note an important difference between this approach and traditional approaches to clinical text. More often, predefined query language (e.g., sets of terms describing smoking status or treatment resistance in depression) is applied to search clinical text. Here, we reverse the typical search process, applying the clinical text (narrative note) to query an external corpus (the set of documents returned by searching the Internet for terms described by the RDoC workgroup statements).

Analysis

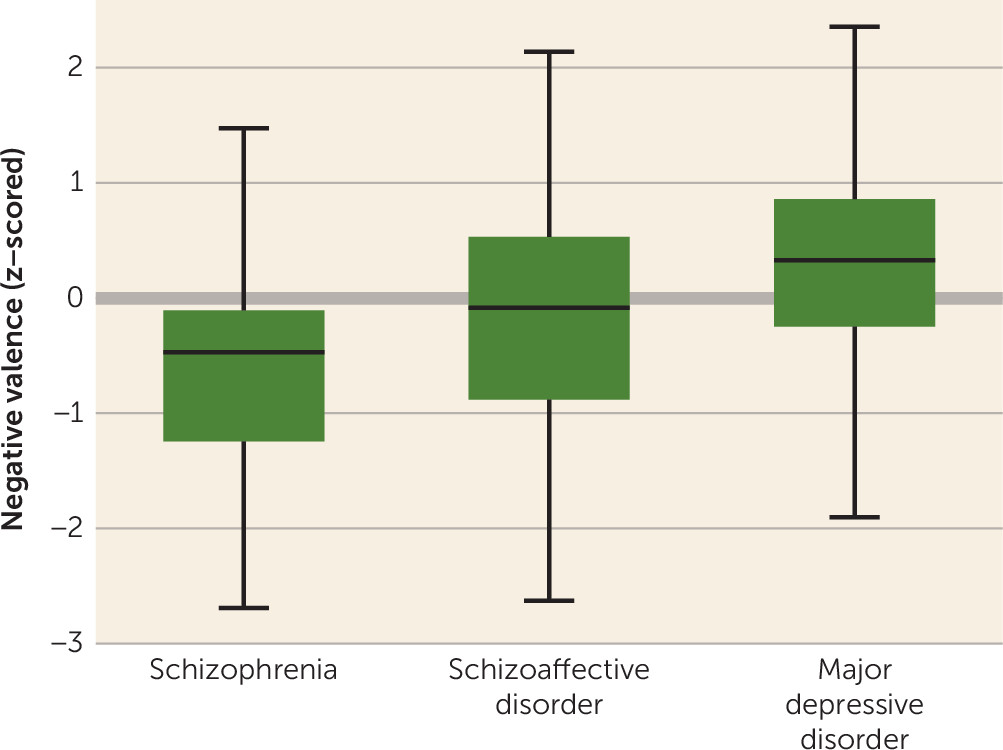

All estimated RDoC (eRDoC) domain scores were z-transformed in order to aid in interpretability. For descriptive purposes, we first examined the distribution of scores across the subset of individuals diagnosed at admission with major depressive disorder (N=327), schizophrenia (N=80), or schizoaffective disorder (N=81). Analysis of variance with post hoc pairwise tests was used to contrast these three groups.

Next, associations between eRDoC domain scores, diagnoses, and length of hospital stay were examined using mixed-effects models, in order to account for multiple clustered observations per patient, among all individuals. First, we fitted a model including demographic variables without these factors; then we added these factors, and the change in model fit was assessed by likelihood ratio test. A standard Bonferroni correction would require a p threshold of <0.01 for statistical significance with an experiment-wide alpha of 0.05.

Finally, time to all-cause hospital readmission after discharge used survival analysis with results censored at readmission, death, or 2 years, whichever came first. Effects of domain scores were examined using Cox proportional hazards models, adjusted for demographic and clinical variables. Analyses were conducted with Stata, version 13 (StataCorp, College Station, Tex.).

Results

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the inpatient cohort are summarized in

Table 1. Given that this was a psychiatric unit in a general hospital, the mean Charlson comorbidity index of 3.4 suggests substantial medical comorbidity. Notably, only about a quarter of individuals were diagnosed with major depressive disorder, schizophrenia, or schizoaffective disorder; other common diagnoses included mood disorder not otherwise specified and psychosis not otherwise specified, which are widely used as “placeholder” diagnoses, further illustrating the complexity and limitations of DSM-5 diagnosis.

Figure 2 illustrates the distribution, in each of the three diagnostic subgroups, of eRDoC negative valence domain scores, a dimension selected because we anticipated it would differ predictably between schizophrenia and major depressive disorder. By analysis of variance, negative valence was significantly greater in patients with schizoaffective disorder and major depressive disorder compared with those with schizophrenia (overall F=27.63; p<0.001; post hoc pairwise tests were significant for all groups [p<0.01]). On the other hand,

Figure 2 also illustrates the substantial overlap between the groups on this dimensional measure.

Next, we examined the predictive validity of eRDoC domain scores.

Table 2 summarizes results of a mixed-effects regression model examining the association between individual scores and length of hospital stay, adjusted for differences in demographic and clinical characteristics. The initial model incorporated only age, sex, race, insurance status, and medical comorbidity. Adding terms for the eRDoC domain scores significantly improved model fit (likelihood ratio χ

2=32.75, df=5, p<0.001). In the adjusted model, both the cognitive and arousal domains were significantly associated with length of hospital stay (

Table 2). Coefficients changed modestly with the addition of ICD-9 diagnosis to the model: for the cognitive domain, the beta coefficient was 3.16 (p=0.003); for the arousal domain, the beta coefficient was −1.93 (p=0.075).

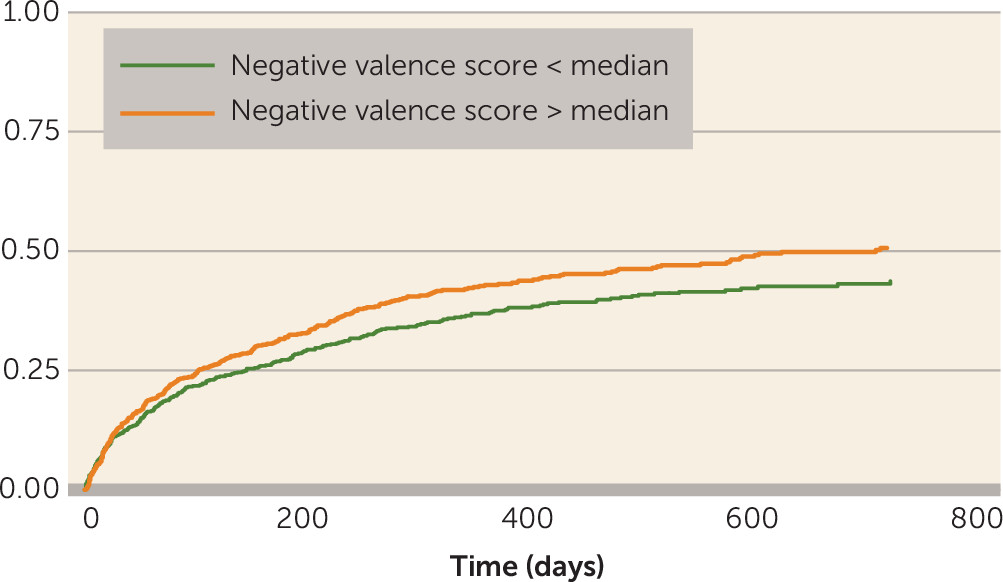

Finally, we examined the association between admission note eRDoC domain scores and time to all-cause hospital readmission after discharge using Cox regression models (see Table S1 in the

data supplement that accompanies the online edition of this article): both the negative valence and social domains were significantly associated with readmission risk; for the negative valence domain, the hazard ratio was 1.95 (p=0.03), and for the social domain, it was 0.59 (p=0.04). Once again, adding ICD-9 diagnosis to the models did not change the coefficients associated with negative and social domains. The association between negative valence score and readmission is illustrated by a Kaplan-Meier survival curve in

Figure 3.

Discussion

In this analysis of data from more than 2,000 patients, leveraging 53,285 documents encompassing more than 89,973,395 words, we demonstrated that eRDoC domain scores are associated with clinically meaningful outcomes, in a manner not fully accounted for by ICD-9 diagnosis code. This result should provide some reassurance to clinicians that their notes do contain relevant detail for deriving dimensional measures of illness: like Molière’s Bourgeois Gentleman, speaking prose without knowing it, clinicians may already speak some RDoC.

We emphasize that these measures are not a substitute for assessment of RDoC domains in individual patients. A key next step before applying our approach more broadly would be clinical validation: comparing estimated domain scores with actual measures of severity using RDoC paradigms nominated by the workgroups. The availability of the software we describe here may facilitate such studies by allowing high-throughput screening of health system cohorts based on existing EHR data, followed by targeted recruitment for prospective validation studies. Before RDoC can truly be used in clinical practice, it will be necessary to derive clinical assessment tools that are relatively brief, are easily implemented and disseminated, and capture at least some of the predictive validity of traditional diagnostic systems. Our work provides some preliminary encouragement that, since clinical features corresponding to RDoC domains are already assessed to some extent in clinical practice, developing clinical tools may be feasible.

For now, clinicians might be best advised simply to be aware of the usefulness of dimensional models to capture psychopathology. Strategies that will render clinical reports more forward-compatible with RDoC include comprehensive psychiatric reviews of systems, characterization of individual symptoms, and, wherever possible, use of clinically valid quantitative measures of symptom domains, recognizing that few of these measures capture a single dimension. For example, while the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology–Self-Report is an efficient and useful means of measuring depressive symptoms, it samples the negative valence, positive valence, social, and even cognitive domains.

Despite these limitations, an advantage of this analysis is that it represents a general clinical population, not a cohort of healthy individuals or a specific ICD-9 diagnosis. This capacity allows us to quantify cross-disorder variation in symptom domains consistent with the intent of the RDoC initiative. To our knowledge,

Figure 2 represents one of the first depictions of how symptoms across multiple diverse domains vary in cross-disorder cohorts—in essence, it provides a snapshot of severe psychopathology in an academic medical center.

Taken together, our results demonstrate the feasibility of applying large-scale scoring of clinical free text drawn from EHRs to characterize RDoC-like symptom dimensions in clinical populations. Clinicians are already accustomed to measuring and describing some symptoms that load onto RDoC dimensions. By enabling EHR data to be used to study symptom dimensions, the approach we describe rescues the massive corpus of narrative notes that describe psychopathology over a decade or more and may help clinicians begin to think in terms of dimensional measures.