When to change the treatment of patients who do not respond to a recently initiated antipsychotic drug is an unresolved clinical question. For decades the dogma of a delayed onset of antipsychotic drug action determined clinical decisions and guidelines in this regard (

1–

6). In 2003, a meta-analysis by Agid et al. (

7) challenged that theory by demonstrating that the greatest symptom reduction occurred during the first weeks of treatment. This “early onset of antipsychotic drug action hypothesis” was corroborated by a subsequent analysis using longer-term, individual patient data (

8). As a consequence, numerous studies have since examined whether the degree of early improvement could predict later response (

9–

27). Most studies showed such associations, but the lack of consensus about the definitions of early improvement and later response made uniform guideline recommendations impossible. For instance, some studies defined early improvement and/or later response as ≥20% reduction in the total score on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), whereas others used a ≥30%, ≥40%, or ≥50% score reduction.

Therefore, the statements in treatment guidelines have remained inconsistent and are often not based on evidence. For example, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) (

28) suggests, “Patients may take between 2 and 4 weeks to show an initial response” on the basis of a small initial study from Correll et al. (

29). The guidelines from the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) (

30,

31) and the World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (

32,

33) recommend waiting for at least 2 weeks before switching medication, but again no solid evidence is provided. The guidelines from the British Association of Psychopharmacology (

34) and from the National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) (

35) recommend trying an antipsychotic at the optimum dose for 4–6 weeks before switching, also without providing firm evidence supporting this recommendation.

Discussion

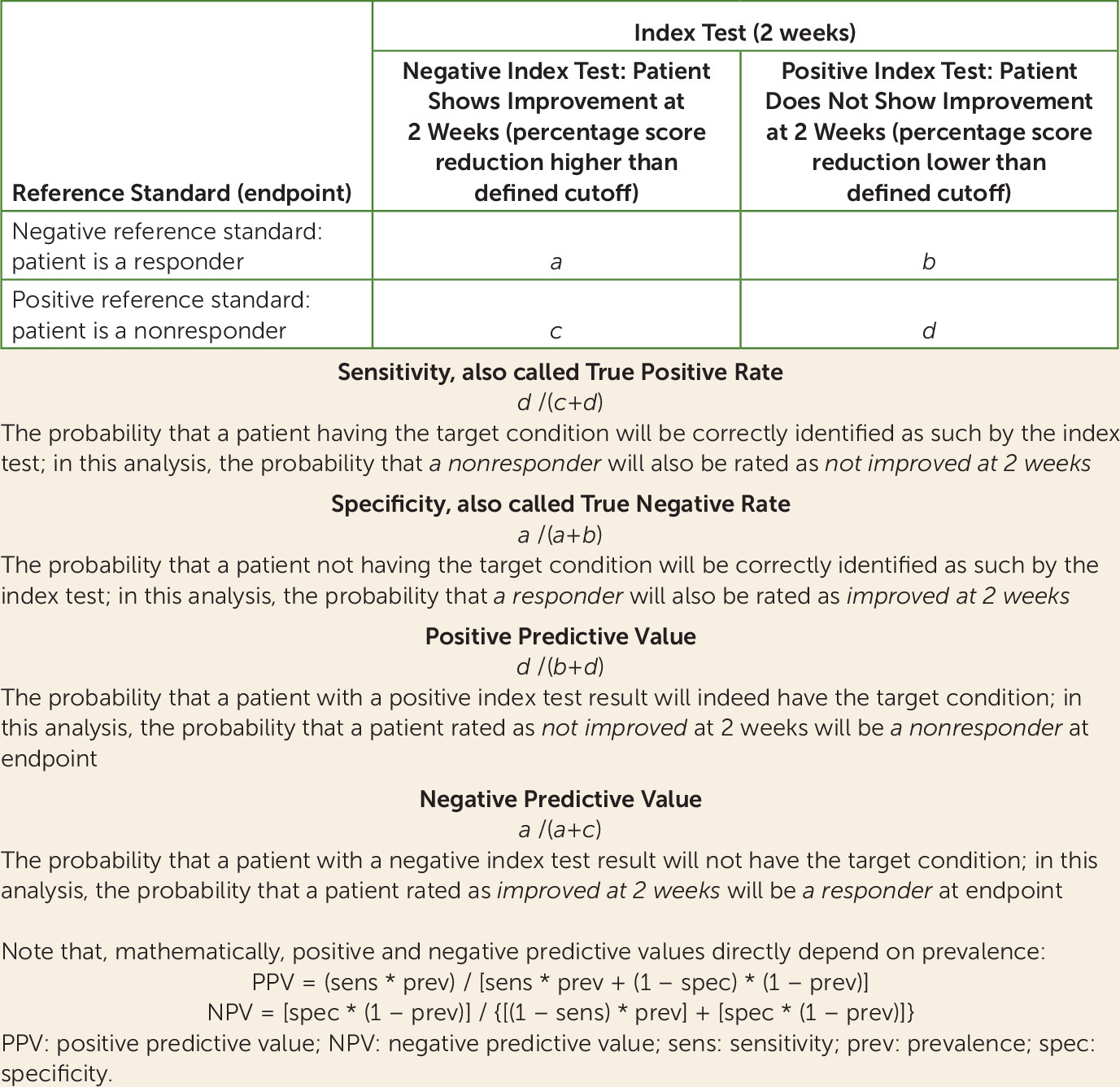

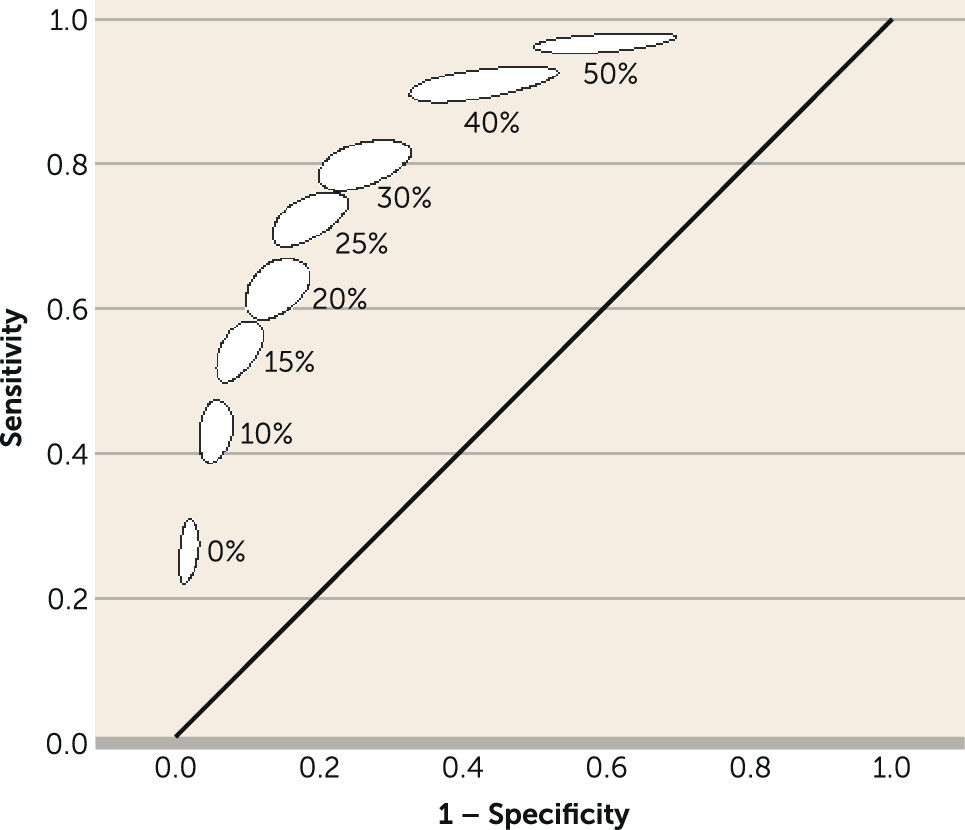

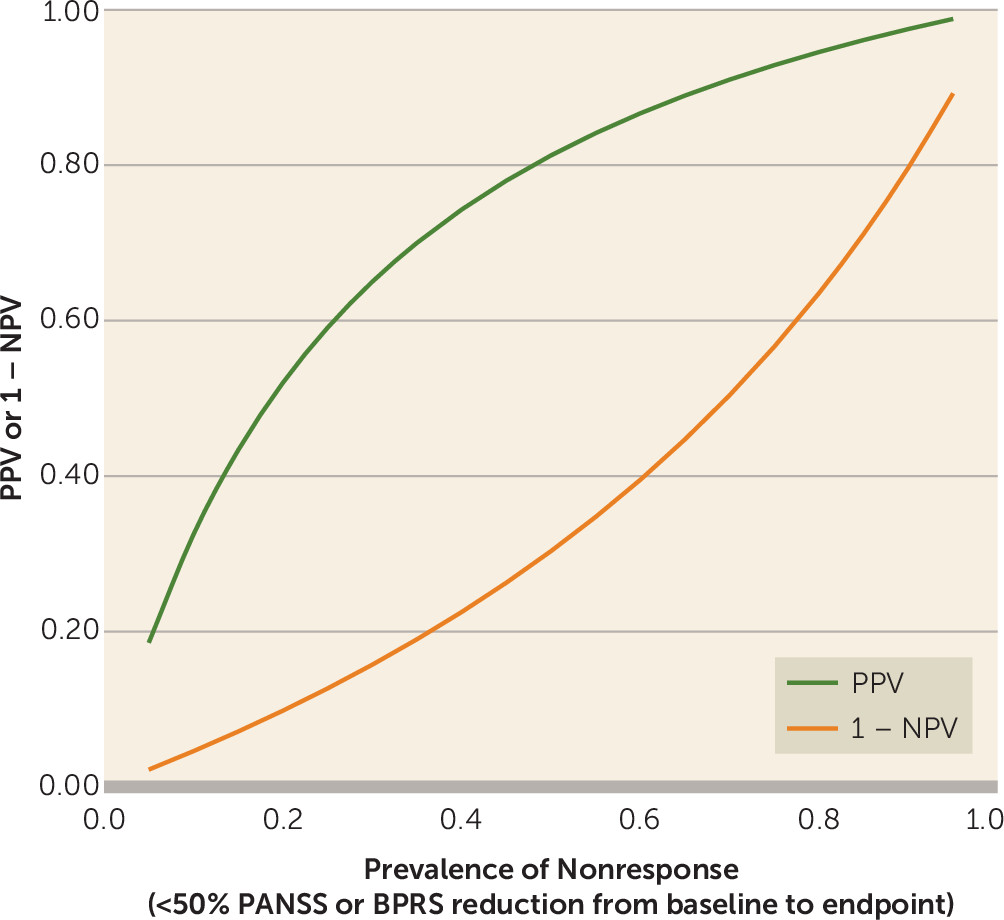

We present a diagnostic meta-analysis with 34 studies and 9,460 participants that examined the question of whether nonimprovement at week 2 predicts later nonresponse to antipsychotics in patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. The major strength of this study is that we were able to obtain individual patient data for almost all trials. The analysis suggested that out of 100 patients showing nonimprovement at week 2 (<20% PANSS or BPRS score reduction), 90 will not show much improvement at endpoint (<50% PANSS or BPRS score reduction), 88 will not achieve symptomatic remission at endpoint, and 55 will not even minimally improve (<20% PANSS or BPRS score reduction).

A ≥50% PANSS/BPRS score reduction from baseline to endpoint is a clinically meaningful definition of response for patients with acute exacerbations of schizophrenia, because it roughly corresponds to “much improvement” as assessed with the CGI (

44,

48). Contrary to common belief, symptomatic remission (

49) has been shown to occur with a frequency similar to that for 50% PANSS or BPRS reduction (

55) and, as a reference standard (here nonremission), yielded results similar to those for the <50% reduction in the diagnostic test meta-analysis. On the other hand, a ≥20% PANSS or BPRS reduction is a much looser definition of response, resulting in a higher number of responders at endpoint (the denominator of specificity) and a significant decrease in specificity and PPV. As a ≥20% PANSS/BPRS reduction reflects only “minimal improvement” (

44,

48), it may not be a good indicator of response (compared with ≥50% and remission). However, a <20% reduction is an extremely stringent measure of nonresponse; most clinicians would change treatment for a patient not even minimally improved after 6 weeks. If one requires at least 80% specificity and PPV for that reference standard, the index cutoff of 0% PANSS or BPRS reduction at week 2 should be applied.

In research on the prediction of response to antipsychotics, many potential predictors have been identified, including early subjective response (

56), severity of illness, homovanillic acid level (

57,

58), structural changes shown by cranial imaging (

59–

61), and polymorphisms of brain receptor genes (

62,

63). However, so far, none of these potential predictors has led to the development of a clinically useful decision-making tool. Early improvement in antipsychotic treatment is the strongest among those predictors (

64–

66), and it is now well replicated and could be implemented in clinical practice. Although many previous studies suggested an association between early improvement and later response (

9,

11,

12,

15,

19,

20,

23,

26,

29,

67), a lack of consensus regarding the definitions of these benchmarks has prevented formulation of straightforward clinical recommendations. For example, if one study used 50% PANSS total score reduction to define ultimate response (

65,

68) while another one used cross-sectional remission (

69), it is difficult to summarize their findings. Moreover, the individual studies usually attempted to derive the best cutoff by post hoc analyses. In the current review, improvement and response were defined a priori.

The specificity of the diagnostic test was shown to be influenced by three independent factors. First, the assessment of final nonresponse at week 4 was associated with higher specificity of the diagnostic test than was assessment of nonresponse at week 6 or later. The number of responders at endpoint (specificity’s denominator) is expected to increase at later endpoints, and thus specificity decreases. Second, higher baseline illness severity was associated with higher specificity of the diagnostic test. For the mean baseline severity of the included patients (score of 97 points on PANSS items 1–7), the specificity was 86%; for 10 points lower baseline severity (87 points), it was 79%; and for 10 points higher (107 points), the specificity increased to 91%. Third, shorter illness duration was associated with higher specificity of the diagnostic test. For the mean illness duration of the included patients (11.5 years), the specificity was 87%; for a duration 5 years shorter, the specificity was 91%; and for a duration 5 years longer, it was 82%.

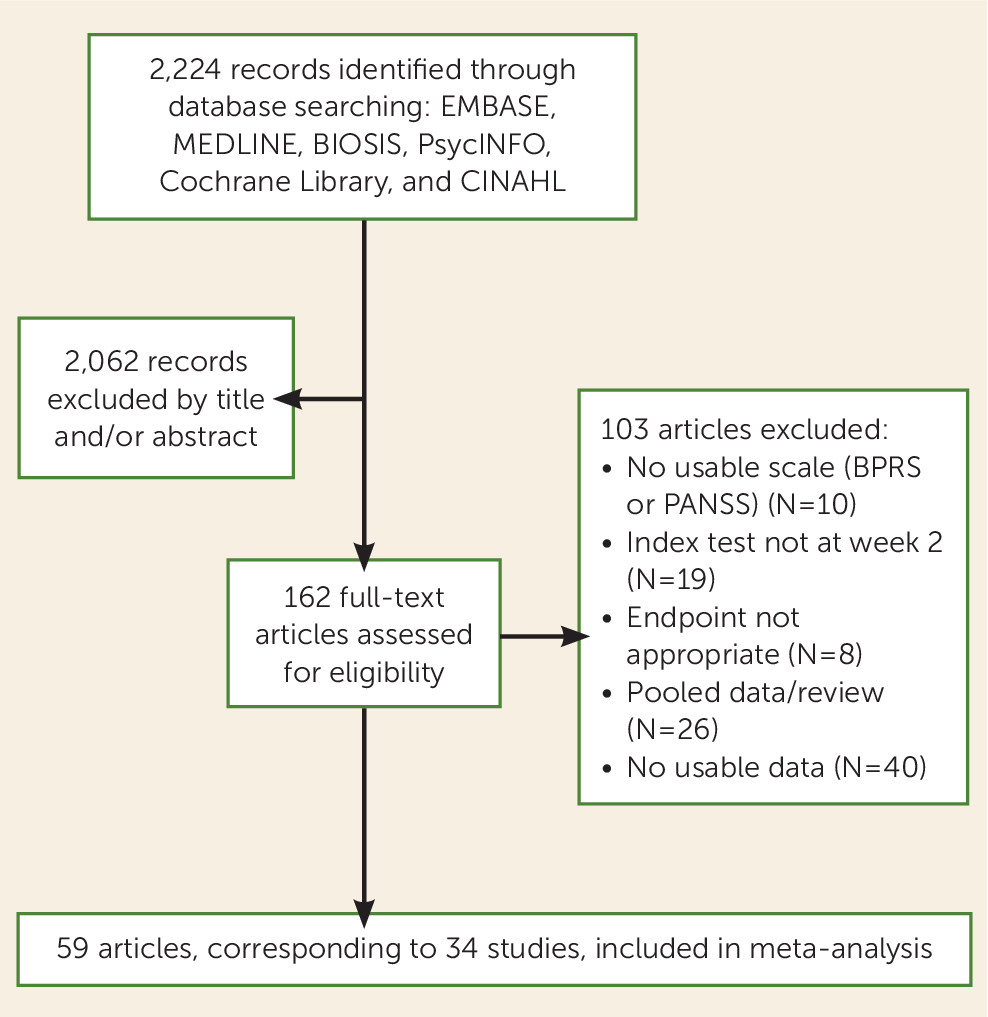

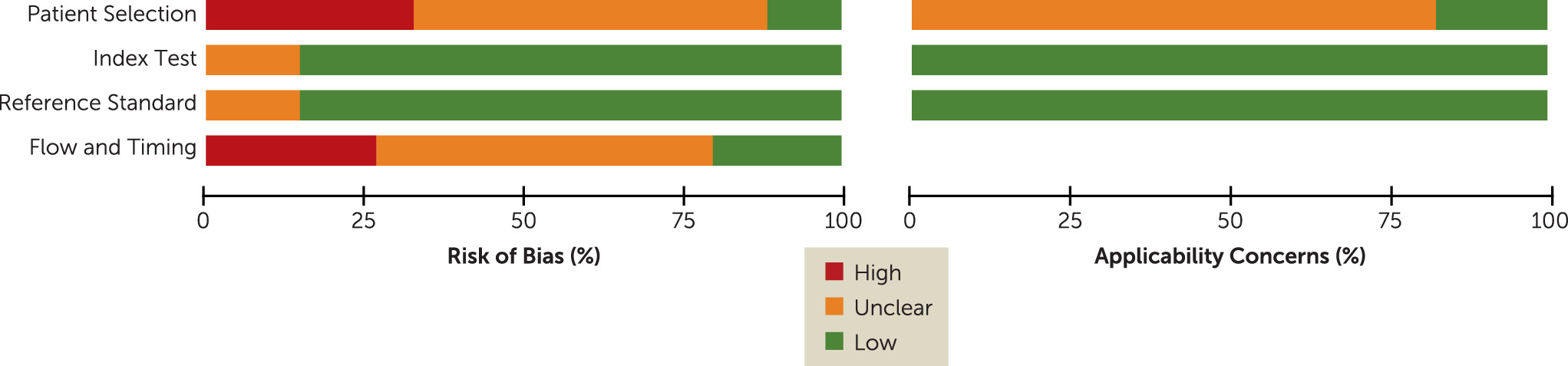

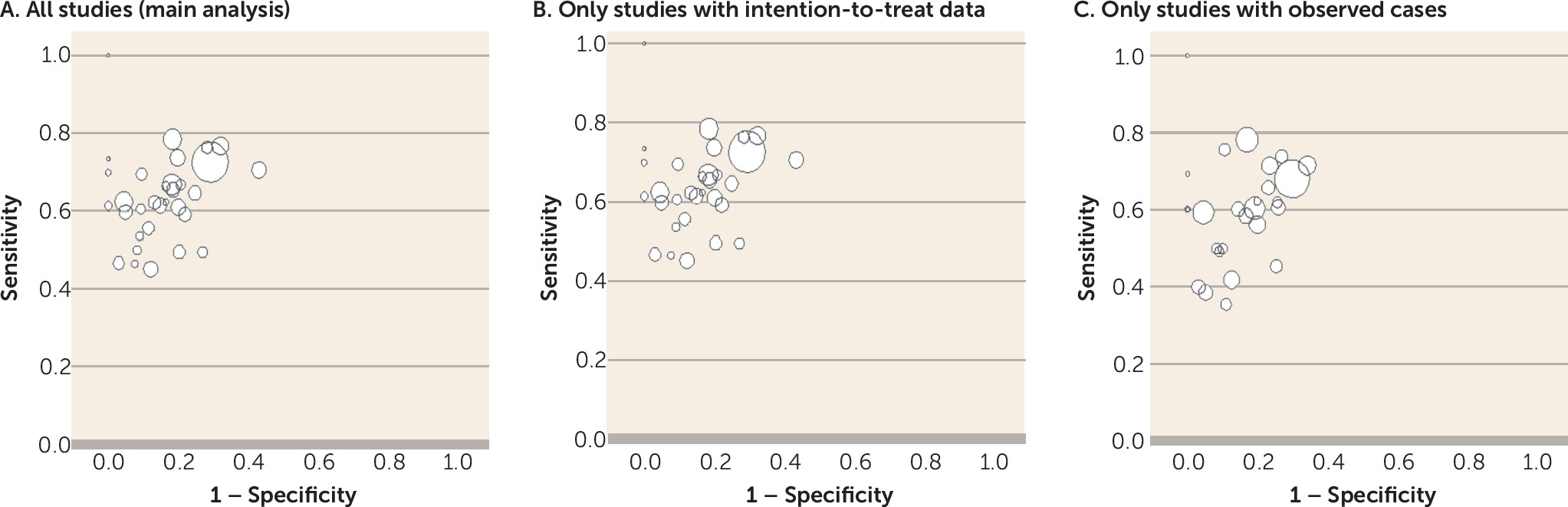

Our meta-analysis has several limitations, some of which are illustrated by the quality assessment with the QUADAS tool (

Figure 2). Of the 34 included studies, 29 were randomized controlled trials and may thus not accurately represent routine clinical practice (

70,

71). However, whether the study was a randomized trial was not a significant moderator of the test performance. As for the high dropout rates usually seen in schizophrenia trials, the comparison of strict intention-to-treat and observed-case results in a sensitivity analysis did not show any significant difference, corroborating the validity of the results.

As all studies were pooled in the primary analysis, it is unclear whether the results apply to all antipsychotics. We had enough data on only four antipsychotics to allow for a comparison of the diagnostic test results among them, but these four drugs may represent a good selection because they cover drugs with quite different profiles. Amisulpride is a selective dopamine receptor antagonist that has no effects on histaminergic receptors and is not sedating. Haloperidol is a high-potency first-generation antipsychotic. Olanzapine and risperidone are frequently used second-generation antipsychotics that block serotonin 5-HT2a receptors more than dopamine receptors, but risperidone produces more extrapyramidal symptoms and prolactin increase, while olanzapine has a higher risk of weight gain and has stronger effects on histaminergic receptors. No obvious difference among these antipsychotics was suggested, but additional analyses of other antipsychotics would be important.

Moreover, when a patient with schizophrenia is administered an antipsychotic medication, immediate anti-anxiety and anti-agitation effects, as well as side effects such as sedation, could be wrongly conceived as early improvement without necessarily an improvement in core symptoms of schizophrenia. In the same vein, the concomitant administration of benzodiazepines and/or adjunctive sleep medication, which were allowed in almost all included trials, could have biased the diagnostic test results, although this is similar to clinical practice, where such drugs are frequently coprescribed as well. We therefore examined whether the use of positive symptoms, instead of overall symptoms, as the index test would change the performance of the diagnostic test, but the results did not change markedly.

Furthermore, our data set contained mainly studies of chronically ill patients. Several studies have shown that response patterns in first-episode patients may differ from those of chronically ill patients, in that at least a subgroup can show later onset of response (

17,

72,

73). Thus, although illness phase was not a significant moderator, this may have been due to an insufficient number of first-episode studies (N=6). Similarly, treatment-resistant patients were represented by only one study in our analysis, and its exclusion in a sensitivity analysis did not change the overall performance of the diagnostic test. Although there is some preliminary evidence that the majority of improvement with antipsychotics occurs relatively early in the course of treatment for treatment-resistant patients as well (

74), a number of studies suggest that longer-term trials are needed when investigating response in this particular subgroup (

75–

78). Therefore, the application of our results is more appropriate for patients who are neither in their first episode of schizophrenia nor exhibiting treatment resistance.

Finally, the translation and scalability of the findings of this meta-analysis to clinical care depend on the use of measurement-based approaches in usual care settings. Since the PANSS and BPRS are not routinely used by clinicians, the well-established correlation between the simple CGI improvement scale and the change in PANSS or BPRS total score (

44,

46,

48) can be taken into account. These analyses have roughly showed that a 20% PANSS or BPRS reduction (our index test) corresponds to minimal improvement on the CGI and that a 50% score reduction (our primary reference standard) corresponds to much improvement. Indeed, a recent naturalistic study that used solely CGI improvement ratings of less than minimally improved at 4 weeks to predict ultimate nonresponse at 12 weeks, defined as less than much improved, confirmed the utility of this approach (

67).

Despite the limitations, the current meta-analysis provides good evidence that nonimprovement at week 2 can be used for a clinically meaningful prediction of later nonresponse, saving patients from unnecessary long-term exposure to an antipsychotic that is unlikely to help them. Notably, some important treatment guidelines, such as those of PORT (

31) and the World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (

32), have already incorporated such statements. It is also crucial to emphasize that, before nonimprovement is established, patients should have received the antipsychotic at a sufficiently high dose. In this meta-analysis, dose titration schedule had no significant effect on the performance of the diagnostic test, but most studies followed a quick titration schedule (target doses were reached within 3 days). Therefore, in order to avoid premature changes of treatment, we caution that the results of this diagnostic test review should be applied only to patients who have received target doses (

41)—we suggest even near the upper limits of these ranges—for at least 2 weeks. This is important, because in everyday clinical practice, doctors often titrate slowly because of tolerability issues, which can be an obstacle to rapid dosage increase. Plasma level measurements can also be useful, e.g., to rule out rapid metabolism due to cytochrome P450 polymorphisms, although plasma levels can vary substantially in individual patients and are not always directly correlated with efficacy (

79).

What this meta-analysis has not explored and future studies need to address is which treatment strategies should be applied in case of nonresponse. Dosage increase is not well studied. Switching has been examined by only a few studies, some of which, clearly underpowered, were negative (

68,

80), while the largest one was positive (

18). Last, augmentation studies have usually focused on treatment-resistant patients at later stages, and they were mainly negative (

81). Results of ongoing studies on switching strategies in patients without early improvement, such as SWITCH (

82) and OPTIMISE (

83), are awaited for replication of previous findings (

18), but alternative and hopefully more effective strategies, pharmacologic and/or psychosocial in nature, that meet clinicians’ and, above all, patients’ needs are warranted.