Evidence indicates that the attention system of anxious individuals is biased toward threat (

1–

4). These findings have led to randomized controlled trials of attention bias modification, which showed moderate efficacy for anxiety disorders (

5–

8). Attention bias modification involves computerized cognitive training strategies designed to alter biases in attention (

9–

11). For example, in protocols intended to shift attention away from threat, response targets appear more frequently at the screen locations of neutral stimuli than at threat stimuli locations, inducing an implicitly learned association between the neutral stimulus and target location that gradually trains attention away from threat (

12–

14).

Given the attentional bias toward threat in anxiety disorder patients, attention bias modification for anxiety disorders such as social phobia (

15,

16) and generalized anxiety disorder (

17) typically trains attention away from threat. However, patterns of threat-related attention in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are more variable than in anxiety disorders; some studies show a bias toward threat (

18–

20), whereas others show threat avoidance (

21–

25). Thus, while threat-related attention biases occur in PTSD, inconsistency in the direction of the findings raises questions about which type of protocol is most appropriate to rectify the observed aberrations—training attention away from threat, training attention toward threat, or applying a training protocol designed to balance fluctuations in threat-related attention bias. Indeed, a tendency for attention to fluctuate between threat vigilance and threat avoidance, called “attention bias variability,” reliably correlates with PTSD symptoms (

26,

27). This may reflect a loss of attentional control and aberrant buffering of attention among participants with PTSD symptoms (

28,

29).

To our knowledge, only two randomized controlled trials have used attention bias modification in PTSD. Schoorl et al. (

30) compared attention bias modification and attention control training and found that the two regimens induced comparable reductions in PTSD symptoms, with no evidence of associations between changes in threat bias and symptoms. Kuckertz and colleagues (

31) administered attention bias modification or attention control training in conjunction with cognitive-behavioral therapy and medication to military personnel with PTSD. While participants receiving either training regimen experienced reductions in PTSD symptoms, the group that received attention bias modification had fewer PTSD symptoms at posttreatment than the group that received attention control training. In that study, change in plasticity of attention bias in the attention bias modification group mediated change in PTSD symptoms.

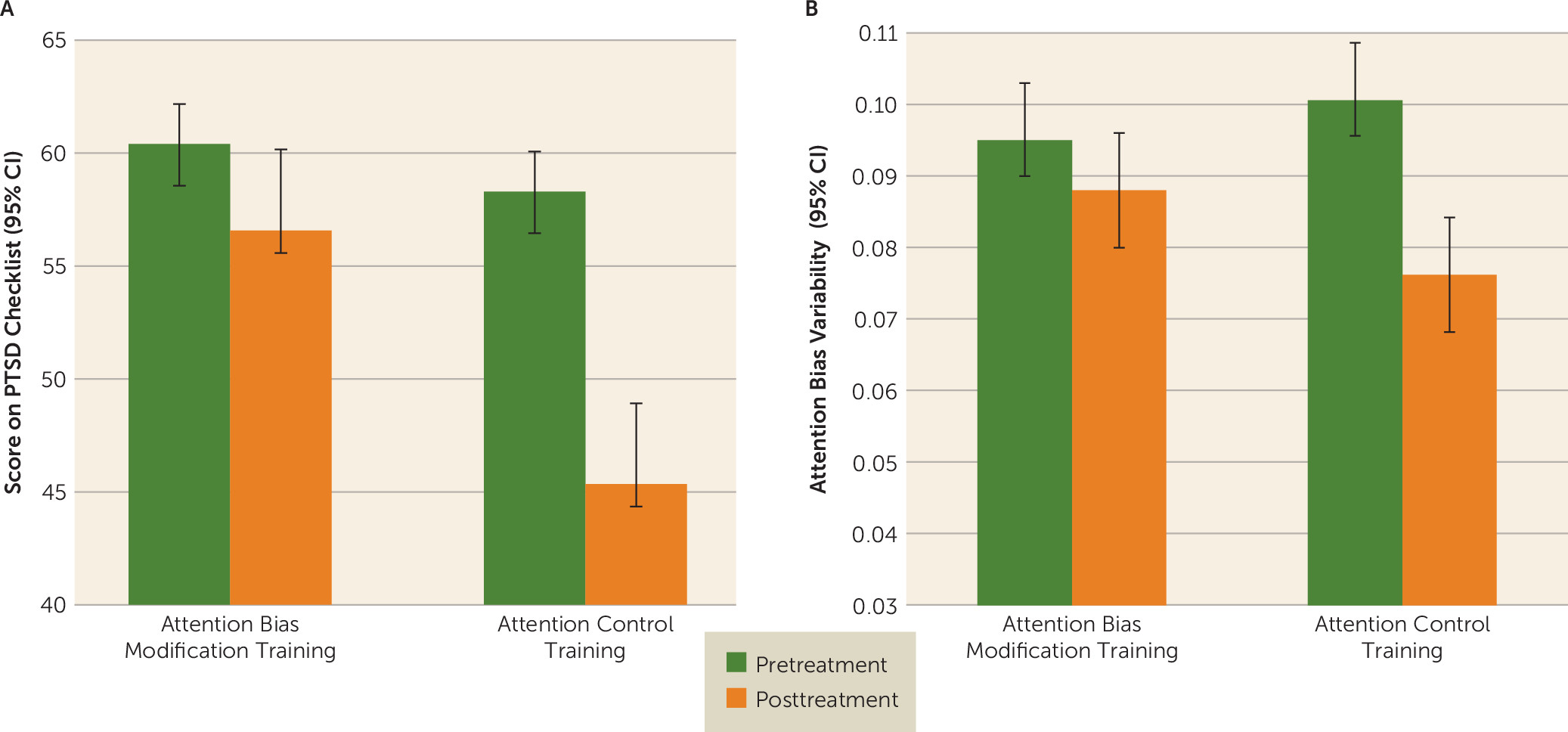

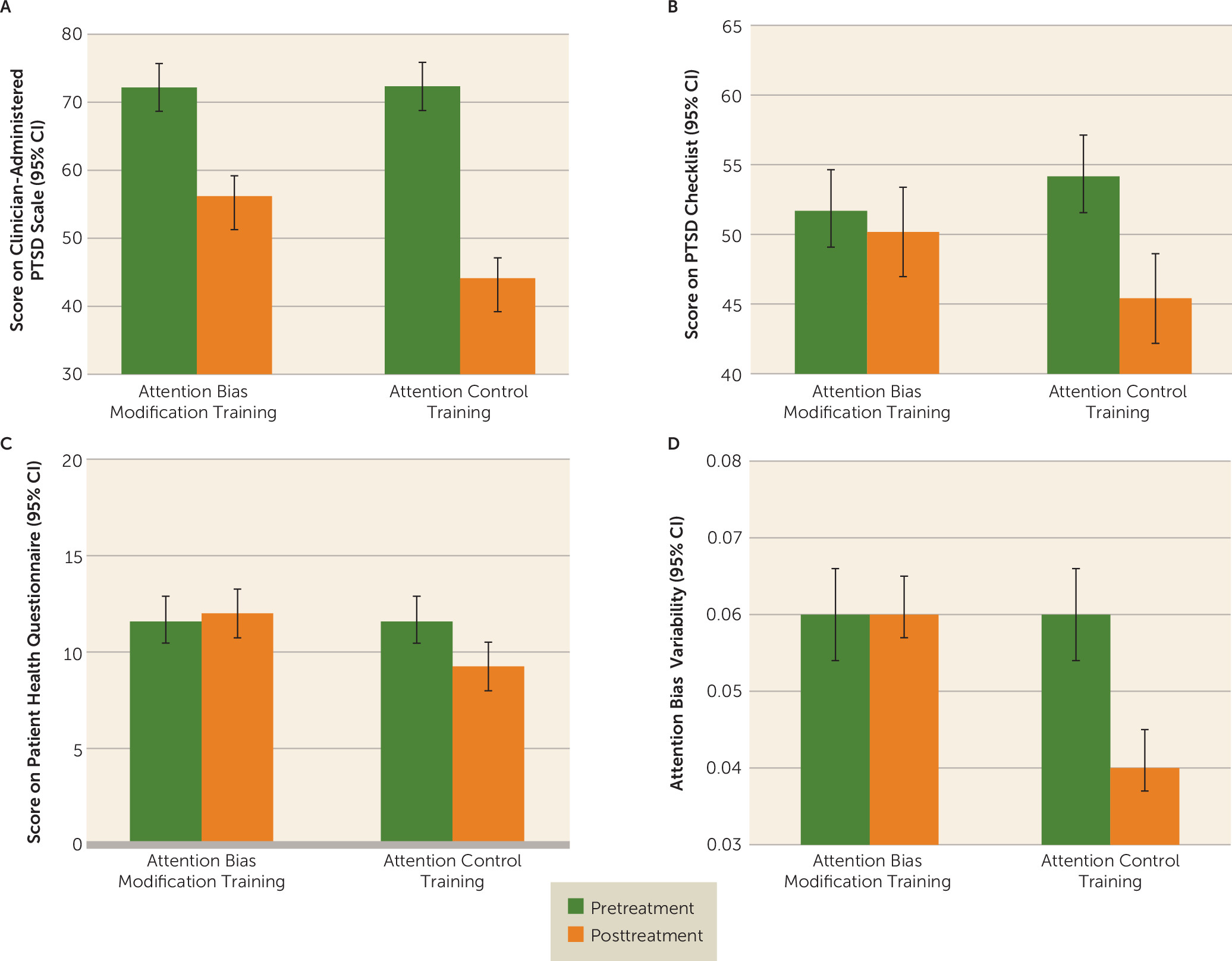

We applied randomized controlled trial designs using variants of the dot-probe task to test the efficacy of attention bias modification versus attention control training in patients with PTSD. We measured changes in symptoms, attention bias, and attention bias variability from pre- to posttreatment. In study 1 we administered four sessions of word-based attention bias modification or attention control training to Israel Defense Forces veterans with PTSD. In study 2 we administered eight sessions of face-based attention bias modification or attention control training to veterans of the U.S. Armed Forces with PTSD.

Discussion

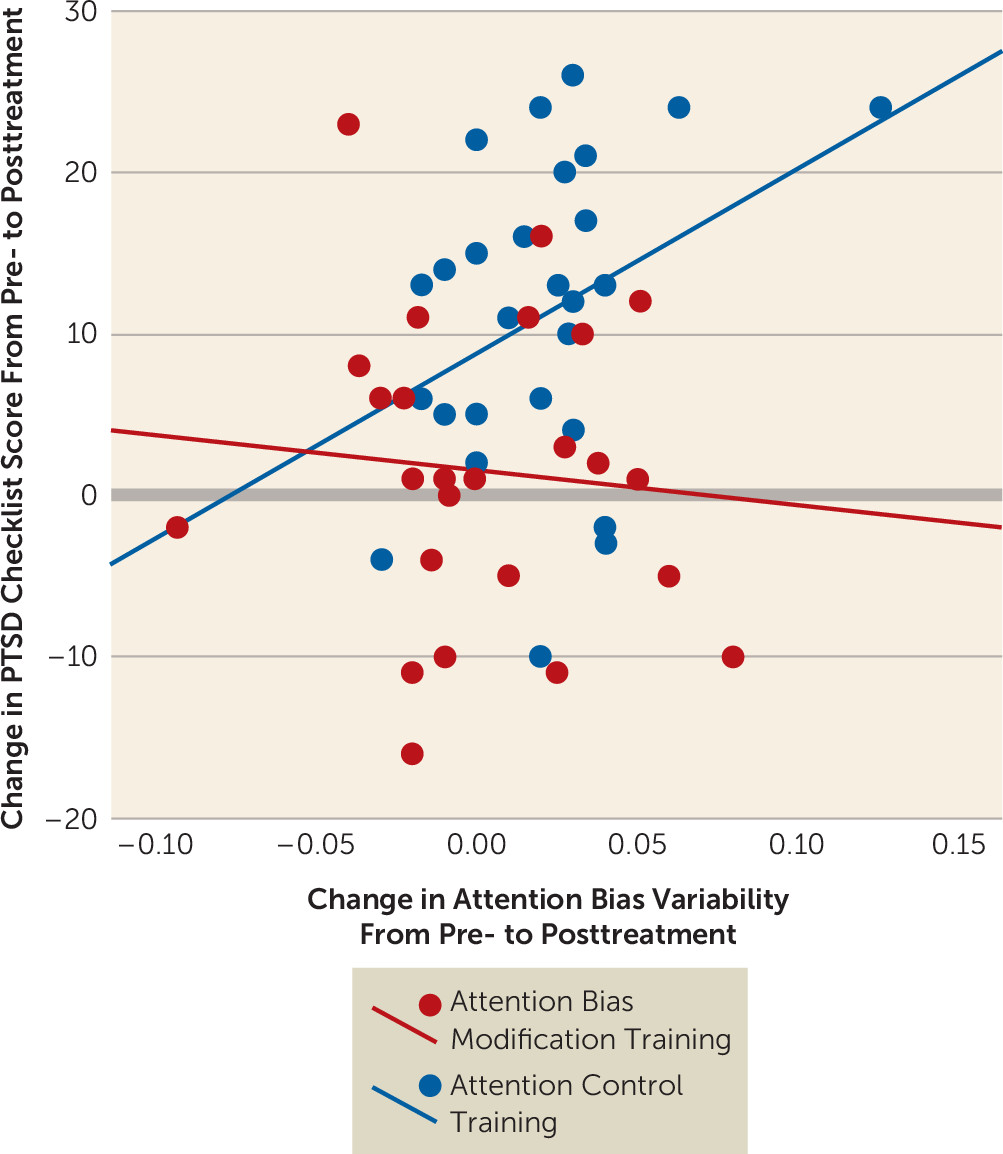

We conducted two separate randomized controlled trials of attention bias modification versus attention control training delivered as stand-alone treatments for combat-related PTSD. These trials were conducted in different countries (Israel, United States) with different stimuli sets (words, faces) and different treatment requirements (four and eight sessions); however, the results of the two trials were similar. Both trials supported attention control training over attention bias modification as the more efficacious training protocol for PTSD symptom reduction. Attention control training, but not attention bias modification, was associated with a decrease in attention bias variability, which has recently been identified as a core attentional perturbation present in PTSD (

26,

27). Combining the two independent samples for mediation analysis revealed that change in attention bias variability mediated the reduction in PTSD symptoms in the attention control training group but not in the attention bias modification group. Neither treatment resulted in change in the classically calculated attention bias score.

The findings in the current study differ markedly from findings in other studies of attention bias modification for non-PTSD anxiety disorders. Whereas attention bias modification typically produces greater effects on symptoms than attention control training for anxiety disorders (

8), we found the opposite pattern for PTSD. Whereas findings in non-PTSD anxiety disorders have been consistent, previous research has shown less consistent attention bias patterns in PTSD, with some research supporting attention bias toward threat (

18–

20) and other studies indicating attention bias away from threat (

21–

25). These disparate findings are consistent with the diagnostic criteria for PTSD, which include both threat vigilance and threat avoidance symptoms. Attention bias toward threat is the mechanism targeted by traditional attention bias modification for anxiety disorders; however, studies not producing the intended effect on attention bias may not reduce symptoms (

11). Although attention bias modification was associated with reduced CAPS scores in study 2 (

Figure 2A), neither of the two studies showed a change in threat-related attention bias. Thus, attention training away from threat is unlikely to represent an underlying mechanism of PTSD symptom reduction. Even so, the significant symptom reduction in the attention bias modification group in study 2 does provide some limited evidence that this training regimen might treat PTSD.

The current results support the importance of attention bias variability as a marker of PTSD, and they demonstrate that a reduction in attention bias variability is associated with reduced PTSD severity following attention control training. These findings resonate with recent reports that higher attention bias variability correlates with more severe PTSD (

26,

27), and they extend this work by indicating that change in attention bias variability induced through attention control training appears to mediate clinical improvement in PTSD. The current findings also correspond with recent research suggesting that within-trial response variability may be a general marker of executive dysfunction in PTSD (

48) and that fluctuations in trial-level bias scores may provide more appropriate expressions of underlying attention bias conceptualizations (

49). Consistent with this emerging literature, attention bias variability appears to capture the attentional shifts toward and away from threat in PTSD more accurately than static measures of attention bias.

Recently Kuckertz and colleagues (

31) suggested that training direction (toward or away from threat) may be less important than establishing the training contingency between emotional stimuli and task completion, which would require top-down attentional control. However, our results suggest that attention control training may be more effective than attention bias modification designed to train attention away from threat, by enhancing attentional control in PTSD. In attention control training, participants respond to probes appearing equally often after threatening and neutral stimuli, essentially requiring that participants ignore irrelevant threat-related contingencies to most efficiently complete the task at hand. In our trials, attention control training appeared to normalize strong within-task fluctuations in threat-related attention bias, which are typical of patients with PTSD (

26,

27). In attention control training, participants implicitly learn that the threatening stimuli, which likely deplete attentional resources in PTSD, are irrelevant to task performance. The emergence of this more balanced attention allocation is supported by the reduction in attention bias variability in the attention control training arm of both trials and by the mediation effect of change in attention bias variability on PTSD symptom reduction noted for attention control training but not for attention bias modification. More research is needed to replicate these findings and to clarify the exact cognitive mechanisms underlying reduction in attention bias variability through attention control training. Understanding could be enhanced by neurophysiological research designed to assess the impact of attention control training and attention bias modification on dynamic brain functioning. Testing of attention bias modification designed to train attention toward threat in PTSD is also in order.

The current studies did not reveal therapeutic effects for depression symptoms. This is consistent with the largely inconclusive evidence for threat-related attention bias and efficacy of attention training in depression (

7). Such effects, when observed in depression, are usually found with sad rather than angry faces and with longer stimulus presentation durations than used here (

50). It is interesting that a previous study found that word-based attention bias modification had no effect on depression, whereas face-based attention bias modification did (

51). Here, study 1 applied a word-based task and found no effects on depression, whereas study 2 applied a face-based task and found a trend-level reduction in depression symptoms. Future research could test training variants that may be effective for both PTSD and comorbid depression.

The results of the current studies should be viewed in light of some limitations and opportunities for further research. First, although high dropout rates are common in PTSD treatment research (

52), future studies of attention training should explore ways to reduce dropouts (e.g., enhance engagement with the task, enhance the treatment alliance). Concerns regarding generalizability due to large dropout rates are alleviated to an extent by the intention-to-treat analyses and the direct replication in two independent studies. Second, given that attention bias variability has emerged as a partial mediator of the reported therapeutic effect, it would be useful to include measures of general attentional control in future studies.

In summary, traditional attention bias modification is thought to reflect an implicitly learned association between stimulus location and target location (

12–

14). In the case of attention bias modification for anxiety, this learning targets attention bias toward threat by training attention away from threat (

5,

9,

53). However, in PTSD no specific direction of attention bias has been ascertained; rather, PTSD is characterized by fluctuations in attention bias, reflected in high attention bias variability. Attention control training requires equal attention allocation to threatening and neutral stimuli and thus appears to balance moment-to-moment fluctuations in attention bias from threat vigilance to threat avoidance (

Table 3). In line with this assumption, our results indicate that attention control training, more so than attention bias modification, not only helps regulate attention bias variability in PTSD patients, but also results in significantly reduced trauma-related distress as assessed by both self- and clinician-reported PTSD severity.