The average individual with bipolar disorder experiences impairing mood symptoms for about 10 years before obtaining an accurate diagnosis (

1–

3). While retrospective studies of adults with bipolar disorder indicate symptom onset during childhood or adolescence, few of these individuals were diagnosed before age 18 (

4,

5). Diagnostic delays have detrimental consequences, including inappropriate treatments, increased hospitalization, and increased suicide risk (

6). Thus, it is crucial to better characterize the prodromal symptoms preceding bipolar disorder onset.

Multiple lines of evidence indicate the presence of significant psychopathology preceding onset of bipolar illness. Based on retrospective studies of both adults and children, sleep disturbances, anxiety, depressive symptoms, affective lability, subthreshold hypomanic symptoms, behavioral dyscontrol, and irritability have been reported to precede onset of bipolar disorder (

3,

7–

9). Many of these characteristics have also been identified in youths at genetic risk for bipolar disorder (

10–

18).

While these findings indicate the presence of prodromal symptoms, their nonspecificity limits their clinical and research utility. To identify a prodrome that might predict bipolar disorder—in parallel with the concept of an ultra-high-risk population in the schizophrenia literature (

19)—prospective studies are imperative. To date, prospective studies have focused primarily on categorical predictors of bipolar disorder, including both subsyndromal and syndromal diagnoses. The most important result to emerge from such studies is that subthreshold hypomanic episodes are an important predictor of bipolar spectrum disorders in depressed adults (

20), depressed adolescents (

21,

22), and offspring of bipolar parents (

23). Major depressive episodes (

23,

24) and disruptive behavioral disorders (

23) also predict onset of bipolar spectrum disorders in genetically at-risk youths. Anxiety disorders precede onset of bipolar disorder in at-risk youths (

25,

26) and are hypothesized to represent an early stage in the development of the disorder (

27).

The Pittsburgh Bipolar Offspring Study (BIOS) recently assessed categorical predictors of bipolar disorder and showed that disruptive disorders, major depressive episodes, and in particular subthreshold manic episodes were associated with development of bipolar disorder in at-risk offspring (

23). Instead of focusing on mood episodes and categorical disorders, we use the same sample to assess whether dimensions are predictive of new-onset bipolar spectrum disorders in at-risk offspring. This analysis first focuses on the impact of dimensional scales at baseline, to answer the following important clinical question: Which aspects of clinical presentation from a single encounter predict a new-onset bipolar spectrum disorder? Next, we assess which dimensions are

proximal predictors of a new-onset bipolar spectrum disorder, and we examine the trajectory of each significant factor prior to conversion (or at last contact). Finally, we combine these predictors into a path analysis to test a model for how significant independent predictors, both at baseline and proximal visit, lead to bipolar onset. We hypothesized that symptoms at baseline would affect the risk of developing a bipolar spectrum disorder in part through more proximal symptoms.

Method

The methods of BIOS have been described in detail in previous reports (

23,

29). All procedures were approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board before the start of the study.

Sample

Parents with bipolar I or II disorder were recruited via advertisements, research studies, and outpatient clinics. Exclusion criteria were a lifetime diagnosis of schizophrenia, mental retardation, or a mood disorder secondary to medical illness, substance use, or medication use. Comparison parents were recruited from the community without regard to non-bipolar psychopathology and were group-matched by age, sex, and neighborhood. In addition to the above exclusion criteria, comparison parents could not have a first-degree relative with bipolar disorder. The study included all offspring 6–18 years of age, unless a child had mental retardation. We used the entire sample for the factor analysis and baseline comparisons. For analyses predicting new-onset bipolar spectrum disorders, we included offspring of bipolar parents only if they did not have a bipolar spectrum disorder at baseline (“at-risk” offspring).

Procedures

Informed consent from the parents and assent from the children were obtained. Parents and participating biological coparents (31%) were assessed by direct interview using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV. The psychiatric history of nonparticipating biological coparents was obtained from the participant parent using the Family History Research Diagnostic Criteria (

30).

At baseline and during follow-up visits, parents and their offspring were interviewed using the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children–Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL) for non-mood disorders and the K-SADS Mania Rating Scale and Depression Rating Scale from the mania and depression items, respectively, on the K-SADS–Present Version, which assess symptoms during the worst week over the past month (

31,

32). Assessments were performed by interviewers trained with the diagnostic instruments and were reviewed by a child psychiatrist; all were blind to parental diagnoses. Summary scores were obtained using clinical consensus, integrating parent and offspring interviews. Parents and offspring completed several rating scales covering a range of psychopathology, including the Child Affective Lability Scale (

33) and the Child Behavior Checklist (

34) (

Table 1; see also the supplemental Methods section in the

data supplement that accompanies the online edition of this article). Socioeconomic status was determined using the Hollingshead Four-Factor Index (

35).

Follow-up evaluations were performed every 2 years to assess for onset of DSM-IV disorders. Kappa coefficients for all disorders were ≥0.70. Date of onset of bipolar illness was set as the first time the participant met criteria for bipolar disorder not otherwise specified or DSM-IV criteria for a manic, mixed, or hypomanic episode. As detailed elsewhere (and described in the Methods section of the

data supplement), operationalized criteria were used for bipolar disorder not otherwise specified (

36). Youths with this diagnosis have family histories of bipolar disorder, suicidality, risk for substance abuse, and psychosocial impairment comparable to those of youths with bipolar I or II disorder (

29,

36–

38) and have roughly a 50% chance of progressing to bipolar I or II disorder within 5 years (

23,

39).

Statistical Analysis

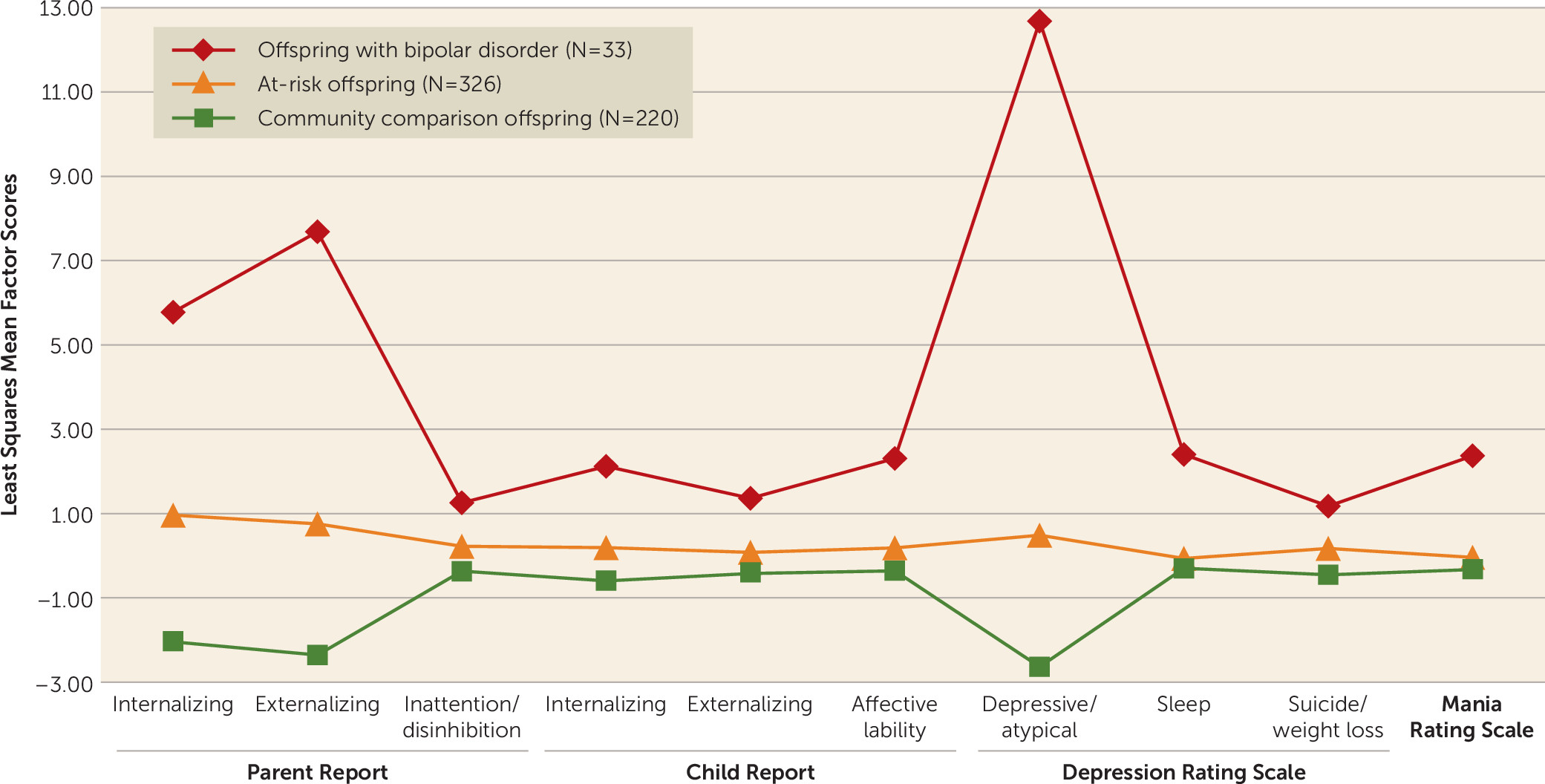

Baseline scales were reduced using maximum-likelihood factor analyses in SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.). The Kaiser rule, the scree test, and Horn’s parallel analysis were used to choose optimal factor solutions. Several rotations were attempted, with the goal of optimizing separation of factors and minimizing items that did not load onto any factors. While all analyses yielded similar factor structures, the final solution included four factor analyses conducted on the entire population utilizing an oblimin rotation: the

parent-report and

child-report factor analyses, based on scales completed by the parent and child, respectively, and the

Depression Rating Scale and

Mania Rating Scale factor analyses, based on the K-SADS Depression and Mania Rating Scales, respectively. For the Depression and Mania Rating Scales, individual items were entered into the factor analyses; for the parent- and child-report factor analyses, we used either full scale scores or, if available, subscale scores based on previous factor analyses (

Table 1; see also the Methods section in the

data supplement).

To mitigate the impact of missing data, we imputed results using multivariate imputation by chained equations. Offspring for whom data were not available for an entire factor analysis (N=46) were excluded. Factor structure did not change with imputation. Rare items (<10 positive responses) were excluded from the factor analysis. If an item loaded on more than one factor (weight >0.3), clinical interpretation was used to determine the appropriate factor. The parent-report, child-report, and Depression Rating Scale factor analyses yielded three factors; the Mania Rating Scale factor analysis did not yield a statistically or conceptually meaningful separation, and so was analyzed as a single factor (

Table 1; see also Tables S1–S3 in the

online data supplement). Factor scores were derived by multiplying each standardized item score by the corresponding factor loading, and then summing the products under each factor.

Differences in demographic and clinical characteristics at baseline among bipolar parents with at least one offspring with a bipolar spectrum disorder, bipolar parents without bipolar offspring, and comparison parents were assessed using standard statistical methods. Characteristics of offspring were compared using mixed-effects regression models, controlling for within-family correlation. Mixed models were also used to evaluate differences in factors across these three offspring groups. Demographic covariates that differed between the three groups (p<0.2) were entered in the analysis; covariates that remained predictors in the multivariate model (p<0.2) were retained. Three comparison offspring had bipolar spectrum disorders at baseline; these youths were excluded from all analyses. Analyses were conducted both with and without adjustment for non-bipolar psychopathology of both biological parents who met the above threshold criteria.

Cox regression was used to determine which factors at baseline were individually predictive of new-onset bipolar spectrum disorders in at-risk offspring, after adjusting for covariates that met the above retention criteria. This method models events according to duration of follow-up, thus indicating the impact of each factor on time to disorder onset. Analyses were adjusted for demographic characteristics, parental non-bipolar categorical diagnoses, and offspring non-bipolar categorical diagnoses (listed in the Methods section in the online data supplement). To assess whether factors were similarly predictive of bipolar I or II disorder, we conducted a sensitivity analysis, removing individuals who had bipolar disorder not otherwise specified at the time of right censorship (i.e., last visit). To determine which factors explained a significant amount of unique variance, a penalized regression model (a “lasso” regression—least absolute shrinkage and selection operator; see the Methods section in the data supplement) including all individually significant predictors of bipolar spectrum disorders was used. We also assessed for interactions between offspring non-bipolar categorical diagnoses and factors to predict new-onset bipolar spectrum disorders. Relevant regression models were used to determine which scales or subscales within each of the predictive factors were driving the observed relationship. All results were adjusted for within-family correlations, using frailty models.

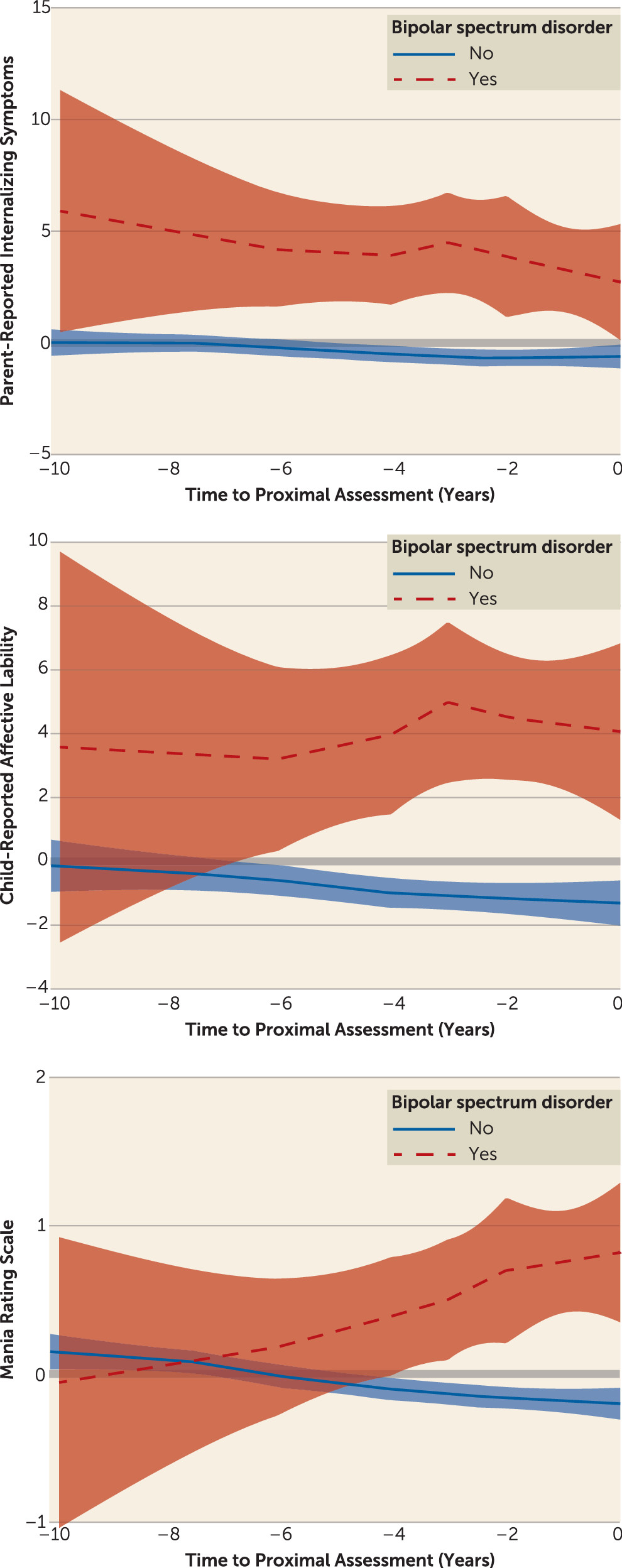

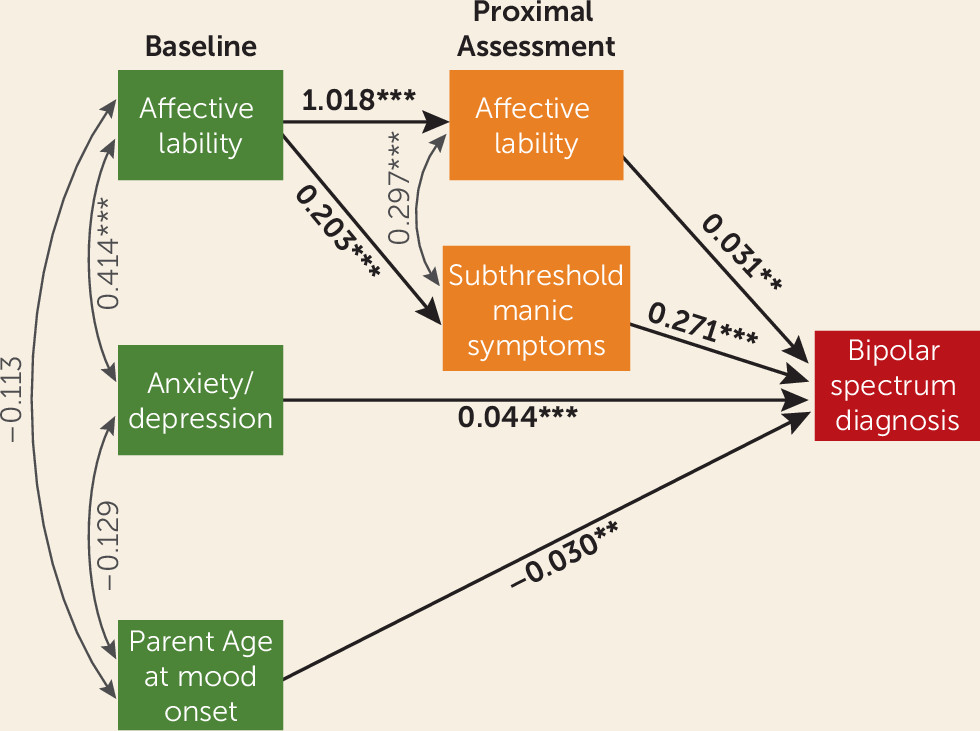

We next assessed factor scores at the visit preceding either bipolar onset or right censorship, using logistic regression to evaluate proximal predictors of bipolar conversion. Similar to intake models, we first assessed whether each factor was individually predictive, and then used lasso regression to determine which factors were independently predictive. All analyses were adjusted for multiple comparisons, covariates that met the above statistical threshold (demographic characteristics, parental diagnoses, and child diagnoses), and within-family correlation. To assess whether group differences persisted across time, we graphed trajectories of independently predictive factor scores up to the point prior to bipolar conversion (or right censorship). Finally, we used a path analysis to test the pathways by which significant baseline and proximal predictors predicted onset of a bipolar spectrum disorder, entering variables that were significant predictors in intake and/or proximal models. Of note, 25 participants had only one visit prior to either bipolar spectrum disorder conversion or right censorship; this visit was used for both the intake and proximal models, but these individuals contributed only to the proximal time point in the path analysis.

Discussion

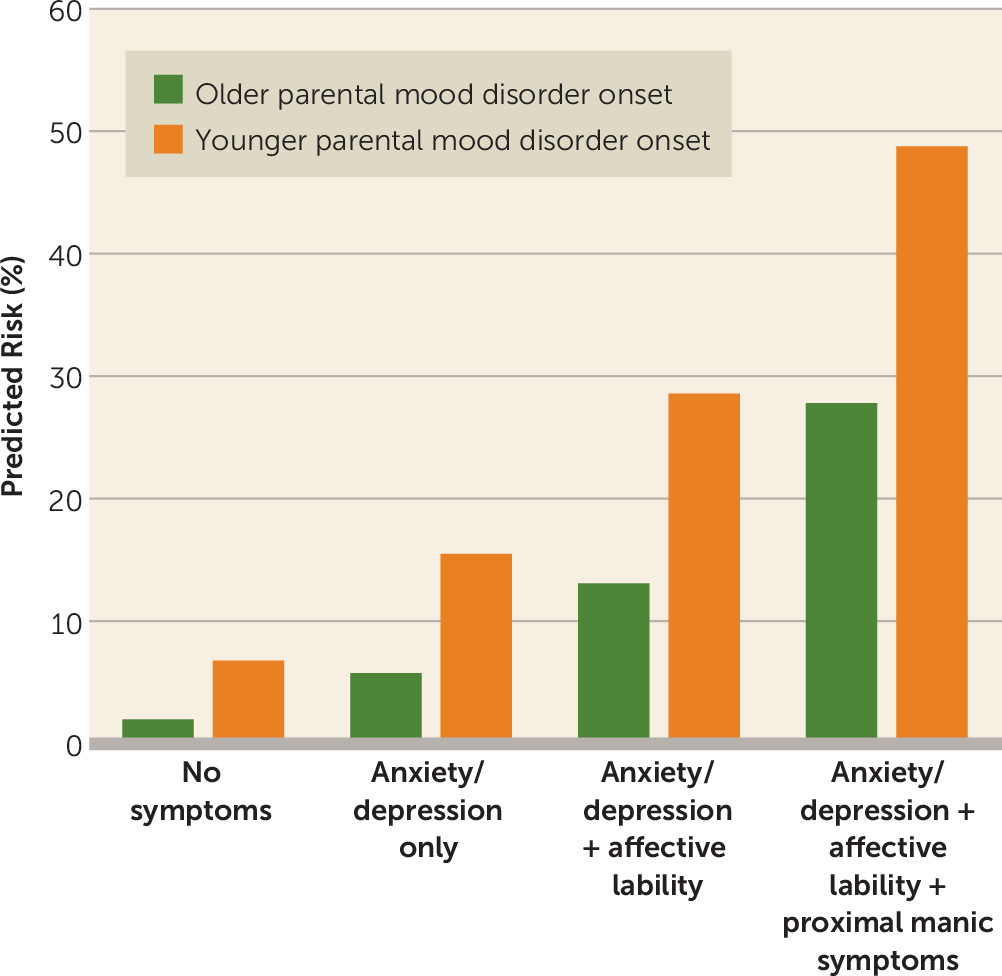

In this sample of at-risk offspring, the most important prospective dimensional predictors of new-onset bipolar spectrum disorders were anxiety/depressive symptoms (baseline), affective lability (baseline and proximal), and subthreshold manic symptoms (proximal). Consistent with previous work (

42,

43), we also found an increased risk of new-onset bipolar spectrum disorders with earlier parental age at mood disorder onset (e.g., before age 18). The predicted risk for an individual with all of these risk factors was more than 24-fold higher than the predicted risk for an individual with none of them. These predictors were significant above and beyond categorical disorders, and, in fact, the disorders were no longer significant predictors of bipolar spectrum disorder onset after taking dimensions into account. Interactions between dimensions and disorders were also not significant, meaning that the effect of dimensions did not differ according to diagnostic category. Trajectory and path analyses indicated that anxiety/depression and affective lability were initial predictors of new-onset bipolar spectrum disorders, and they remained consistently elevated in those who would go on to convert. In contrast, manic symptoms increased up to the visit prior to conversion; affective lability at baseline predicted new-onset bipolar spectrum disorders in part through the increase in manic symptoms at the proximal visit.

While affective lability emerged as an important predictor of new-onset bipolar spectrum disorders in this analysis, this symptom might not be regularly assessed by clinicians. In this study, and in previous work (

17), we used the Child Affective Lability Scale (parent- and child-report versions) to assess this domain, which factors into three symptom categories: depression/anxiety, irritability, and subthreshold mania. Thus, this freely available self-report may be used to screen offspring of parents with bipolar disorder who are at risk of developing the disorder.

Although child and parent reports were found to be important for different domains, the present study does not provide evidence that informant is relevant; rather, the effect is likely an artifact of collected scales. Regarding internalizing symptoms, we did not have a child equivalent of the Child Behavior Checklist, which drove the association of parent-report internalizing with new-onset bipolar disorder. While both parents and children completed the Child Affective Lability Scale, the parent report factored into separate domains, while the child-report factored together; thus, there was no parent-reported affective lability factor, per se. Thus, we draw our conclusions about the domains rather than the informants.

These findings build on a recent analysis from the BIOS study that identified subsyndromal manic episodes as an important categorical predictor of bipolar disorder (

23). We add to this work by finding that subsyndromal manic symptoms (even in the absence of a mood episode) predict bipolar spectrum disorder onset in at-risk youths. Our results are also consistent with findings from retrospective and at-risk studies that point to a wide-ranging set of prodromal symptoms, in particular anxiety/depression (

26,

27), affective lability (

17,

44,

45), and subthreshold manic symptoms (

45,

46; see reference

9 for a review). We found that almost all dimensions are elevated in youths at risk for bipolar spectrum disorder (as compared with community comparison offspring). However, we add to these previous findings by assessing the degree to which each dimension prospectively and independently predicted bipolar spectrum disorder onset, even after adjustment for parental and offspring non-bipolar disorders. Using longitudinal data, we also begin to define both an “initial” prodrome for bipolar disorder (which can occur up to 7 years before disorder onset [

47]) and a “proximal” prodrome (2 years before onset). From a single clinical encounter, anxiety/depression and affective lability are the best predictors of future new-onset bipolar spectrum disorders (“initial” prodrome). Progressively increased subsyndromal manic symptoms (along with affective lability) emerge as the most important predictors of conversion within the next 2 years (“proximal” prodrome). Of note, more than half of the youths with these symptoms did not develop bipolar spectrum disorders within the follow-up period; thus, the presence of this prodrome does not imply that they will necessarily develop a disorder, but rather it identifies the youths who are at highest risk of conversion.

This study has several strengths on which we capitalized in this analysis. First, the sample size and length of follow-up led to adequate numbers of youths developing de novo bipolar spectrum disorders, allowing the prospective assessment of predictors of onset and differentiating them from consequences or correlates of disorder onset. Second, we collected data on a large number of both self-report and clinician-administered scales at baseline, allowing for a comprehensive assessment of mood, anxiety, and behavioral dimensions that could be potentially predictive of disorder onset. Thus, we did not constrain our analyses based on theory, but rather used a data-driven approach to identify independent predictors of disorder onset. Third, data were available regarding parental and offspring demographic and clinical characteristics. Adjustment for such variables established that observed associations were related to bipolar spectrum disorders, and not confounded by these factors.

This study also has limitations, which should be kept in mind when interpreting the results. First, we focused on the predictors of bipolar onset in at-risk offspring; thus, we do not know if the results would generalize to a population without such a familial risk. Second, visits were scheduled every 2 years, so the “proximal” time point was often 1–2 years before conversion to a bipolar spectrum disorder. Because of this, our analyses may have missed prodromal symptoms that appeared within only months of disorder onset. Third, while we had adequate numbers of new-onset bipolar spectrum disorders to assess predictors, we had relatively few youths with bipolar I or II disorder. However, we had enough power to conduct a sensitivity analysis, which revealed findings consistent with the primary model, thus mitigating this concern to some extent. Power to test interactions between dimensions and categorical disorders was also limited, rendering this analysis exploratory. Fourth, our average age at baseline was under 12 years, and many of the at-risk offspring might yet develop bipolar disorder (particularly those with major depression), since some are only entering the high-risk period for developing the disorder. Thus, our findings may apply preferentially to cases with earlier onset, as opposed to those who develop a bipolar spectrum disorder during adulthood. Young age at baseline may also explain discrepancies between our sample and other at-risk cohorts, such as the fact that substance abuse did not differ across baseline groups (see reference

23 for a full discussion). Fifth, our sleep variable consisted only of items from the K-SADS Depression Rating Scale and thus did not rigorously characterize sleep. Circadian dysfunction, when measured more directly, may predict new-onset bipolar disorder.

Despite these limitations, our findings have important implications. We found that a diverse array of dimensional psychopathology is associated with family history of bipolar disorder. However, a smaller subset of symptoms predict bipolar spectrum disorder onset, above and beyond the presence of categorical diagnoses. From a single assessment, anxiety/depression and affective lability should raise clinical suspicion that an at-risk youth will develop a bipolar spectrum disorder in the future, particularly in those whose parent(s) developed a mood disorder at an early age. As these youths are followed in time, the persistence of affective lability and the emergence of manic symptoms markedly increase the risk of conversion to a bipolar spectrum disorder within the next few years. Clinically, this more specific set of prodromal symptoms may identify youths who would benefit particularly from early pharmacological and/or psychosocial interventions and increased surveillance. From a research perspective, the definition of an “ultra-high-risk” population might facilitate the identification of biomarkers and the evaluation of early interventions.