The central public health challenge in the management of winter seasonal affective disorder (SAD) (

1) is prevention of depressive episode recurrence over subsequent winters. Light therapy, the most studied treatment, is highly efficacious for acute SAD (

2). However, long-term compliance with clinical practice guidelines recommending daily light therapy during the symptomatic months each year is poor. Most patients fail to reinitiate light therapy in subsequent winters (

3), leaving them vulnerable to recurrence without other treatment. Cognitive-behavioral therapy tailored for SAD (CBT-SAD) (

4) is an emerging, time-limited, alternative treatment. Whereas light therapy targets a chronobiological vulnerability, CBT-SAD targets a psychological vulnerability, specifically maladaptive thoughts through cognitive restructuring and avoidance behaviors through behavioral activation, to alleviate current symptoms and prevent future recurrences. Attenuated risk for relapse and recurrence of nonseasonal major depression following cognitive therapy is well documented (

5). If the effects of CBT-SAD endure after treatment to prevent recurrences, it may offer a more practical method of managing long-term SAD symptoms than reinitiating daily light therapy each year.

Pilot studies found that CBT-SAD and light therapy showed comparable improvements during treatment (

6), but CBT-SAD was associated with fewer recurrences and less severe symptoms at naturalistic follow-up the next winter (

7). The first wave of our new, largest randomized trial found large and comparable improvements in CBT-SAD and light therapy over the acute treatment phase (

8). At treatment endpoint, the treatments did not differ on patient- or rater-assessed depression severity or on the proportion of patients in remission (47.6% in CBT-SAD compared with 47.2% in light therapy). The present study focuses on the primary aim of that project: to compare the long-term efficacy of CBT-SAD compared with light therapy one and two winters following treatment. We hypothesized that CBT-SAD would be associated with a smaller proportion of depression recurrences, less severe symptoms, and a larger proportion of remissions than light therapy over follow-up.

Method

Design Overview

This trial was conducted at the Mood and Seasonality Laboratory at the University of Vermont and was approved by the university’s institutional review board. The enrolled sample of patients (N=177) was randomly assigned to 6 weeks of CBT-SAD or light therapy and prospectively tracked through two new winters following treatment endpoint. Previous reports detail our full protocol (

9) and report baseline characteristics, treatment integrity, and acute treatment outcomes (

8). Participants were aged 18 or older and met DSM-IV-TR criteria for major depression, recurrent, with seasonal pattern on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID) and a current SAD episode on the Structured Interview Guide for the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale-Seasonal Affective Disorder Version (SIGH-SAD) (

10) (same criteria as for recurrence, as described below). Exclusion criteria were kept to a minimum to maximize external validity. Potential participants were screened out for current light therapy or psychotherapy for depression, prior light therapy or CBT for SAD, a comorbid axis I disorder primary to SAD requiring immediate treatment, acute and serious suicidal intent, initiation of a new antidepressant medication in the past month or plans to change the dose of a current antidepressant, or positive laboratory findings for hypothyroidism at medical workup.

Power

The study was powered to detect clinically meaningful differences between treatments on SAD recurrences (primary outcome) following treatment of the index episode. With these sample sizes (CBT-SAD, N=88; light therapy, N=89), there was 80% power to detect differences between treatments of 0.21 in recurrence proportions and ≥3.6 points in SIGH-SAD scores at follow-up.

Treatments

Light therapy.

We used the 23×15½×3¼-inch SunRay (SunBox, Gaithersburg, Md.), which emits 10,000 lux of cool-white fluorescent light through an ultraviolet filter, initiated at 30 minutes immediately upon awakening. Weekly clinical adjustments were made per a treatment algorithm, in consultation with our study psychiatrist and light therapy expert, to maximize treatment response and reduce side effects. Final doses of light therapy were reported by Rohan et al. (

8). Participants were advised to continue with daily light therapy until their typical time of spontaneous remission, then to return the light boxes in May.

CBT-SAD.

CBT-SAD (

4) uses psychoeducation, behavioral activation, and cognitive restructuring to specifically target winter depression. The format involves 90-minute closed-group therapy sessions twice per week for 6 weeks (12 sessions). Each group was facilitated by the principal investigator (K.J.R.) or one of two community Ph.D.-level psychologists. Session attendance descriptive statistics and analyses for therapist and group membership effects (all were nonsignificant) were reported by Rohan et al. (

8).

Standardized Instructions for Continued Study Treatment the Next Winter

The first week of September, letters were mailed to participants treated the winter before, prompting resumption of study treatment. For light therapy-treated participants, the letter encouraged reinitiating daily light therapy upon onset of the first depressive symptom and provided two options: borrowing a study light box for the duration of the winter or purchasing a unit. The letter provided contact information for manufacturers, with a list of specifications to match our devices (i.e., full-sized units emitting 10,000-lux cool-white light through ultraviolet filter). For CBT-SAD-treated participants, the letter encouraged use of the skills learned in CBT-SAD on their own (without a therapist). Both letters stated that if the recommended strategy proved insufficient, participants should pursue formal treatment, and contact information for local mental health centers and treatment providers was included. These letters were intended to promote fidelity with study treatment over follow-up, while addressing ethical concerns about proscribing additional treatment, if needed.

Outcome Measures

The 29-item SIGH-SAD (

10) includes the 21-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) and the 8-item atypical symptoms subscale. The primary outcome was SIGH-SAD recurrence status as assessed at the next- and second-winter follow-ups, indicated by a total SIGH-SAD score ≥20, HAM-D score ≥10, and atypical score ≥5. Other SIGH-SAD-derived outcomes at the next- and second-winter follow-ups included continuous depression scores (total score, as well as HAM-D and atypical scores) and remission status. Remission status was classified as either ≥50% improvement in the SIGH-SAD score from pretreatment to follow-up plus a follow-up HAM-D score ≤7 plus a follow-up atypical score ≤7 or a follow-up HAM-D score ≤2 plus a follow-up atypical score ≤10. A second blind rater rated audio recordings of the SIGH-SADs. Intraclass correlations for interrater reliability were 0.965 at the next winter and 0.967 at the second winter.

The Beck Depression Inventory-Second Edition (BDI-II) (

11), a 21-item self-report measure of depressive symptom severity, was also administered at the next winter and second winter. BDI-II outcomes at follow-up included total scores and a cutoff score ≤8 as a secondary marker of remission, consistent with our prior trials.

Follow-Up Assessment Procedures

Phone tracking of recurrences and re-treatment.

Participants were contacted twice by telephone (in October and December) in the interim between treatment completion and the in-person next-winter follow-up to track recurrences and new treatments initiated. These tracking procedures were implemented starting with the second enrolled cohort (N=153; CBT-SAD, N=76; light therapy, N=77). These calls were conducted by a trained, blinded clinical psychology graduate student and involved 1) assessing DSM-IV-TR criteria for a major depressive episode on the SCID since the date of last contact (i.e., formal assessment or last tracking call) and 2) documenting any treatments initiated since the last contact using scripted questions about light therapy, psychotherapy, and medications.

In-person next-winter and second-winter follow-up visits.

In-person visits were conducted in January or February of the next winter and the second winter. Consistent with the intent-to-treat principle, all randomly assigned participants were invited to attend follow-ups. A trained clinical psychology graduate student, blind to treatment assignment, administered the SIGH-SAD interview, the BDI-II, and a questionnaire assessing use of light therapy, psychotherapy, and medications since the initial study treatment (at the next winter) and since the next-winter follow-up (at the second winter).

Statistical Analyses

The primary analysis was an intent-to-treat analysis based on multiple imputation of missing next-winter SIGH-SAD scores, which were then used to classify depression recurrence status for individuals who dropped out during the treatment phase, withdrew from protocol, or were subsequently lost to follow-up. The fully conditional specification regression method was used to obtain imputed values based on age, sex, baseline comorbid diagnosis status, and depression scores at other time points. Separate regressions were used to impute values for the CBT-SAD and light therapy conditions because of differing effects of the predictors in the two treatments. Imputed values included a random component reflecting the residual distribution for the dependent variable, and 10 data sets with differing imputed values were generated. The difference between the CBT-SAD and light therapy groups in the proportions of participants with a recurrence and in remission the next winter was estimated for each of the 10 imputed data sets, and the estimates were combined using the inference methods for multiple imputation described by Little and Rubin (

12). SAS PROC MI and PROC MIANALYZE were used to carry out the imputation and analysis. Sensitivity analysis was conducted to examine the robustness of the results under alternative imputation methods, including using the best- and worst-case scenarios for each treatment and using a logistic regression in the multiple imputation analysis to directly impute recurrence (rather than linear regression to impute SIGH-SAD scores). The BDI-II outcomes were analyzed in the same manner, as were outcomes for the second-winter follow-up. Analyses based on available data, without imputation, were also performed using logistic and linear regression analyses for dichotomous and continuous outcomes, respectively. In addition to prospectively assessed SIGH-SAD recurrence status, analyses using available data were performed for fulfilling DSM-IV-TR major depression criteria for the interims assessed by the October and December tracking telephone calls. For dichotomous outcomes that differed by treatment at next- and second-winter follow-ups, logistic regressions were performed to assess the effect of treatment group after adjustment for ongoing treatment(s) reported at that time point using data without imputation. We considered any treatment(s), in general, and any new treatment, psychotherapy, light therapy, and antidepressant medications, specifically. When coded for analysis, light therapy-treated patients reporting light therapy were counted as light therapy but not as any new treatment, and psychotherapy with a therapist among CBT-SAD patients was considered as both psychotherapy and any new treatment. For continuous outcomes that differed by treatment, linear regressions were used to assess the effect of treatment on depression scores after adjustment for any, new, and each ongoing treatment.

Results

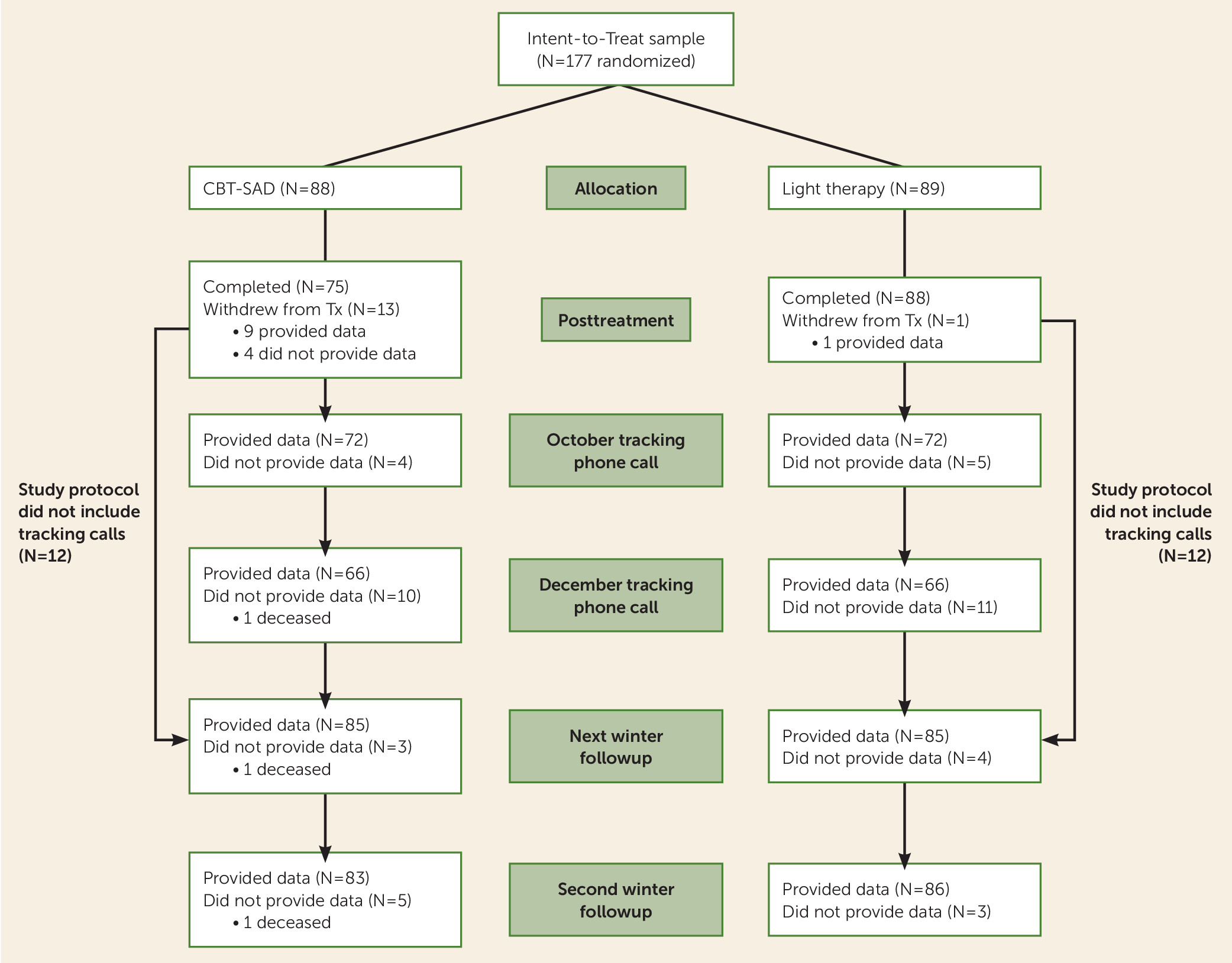

The CONSORT flow diagram from the point of randomization through the fall tracking telephone calls and the next- and second-winter follow-ups is displayed in

Figure 1. For prior stages of participant flow, including screening, see Rohan et al. (

8). Missing data were minimal. At the in-person follow-ups, 170/177 participants (96%) provided data the next winter and 169/177 (95%) provided data the second winter. Of those enrolled after the initial year, 144/153 (94%) and 132/153 (86%) completed the October and December tracking calls, respectively.

Primary and Secondary Outcomes

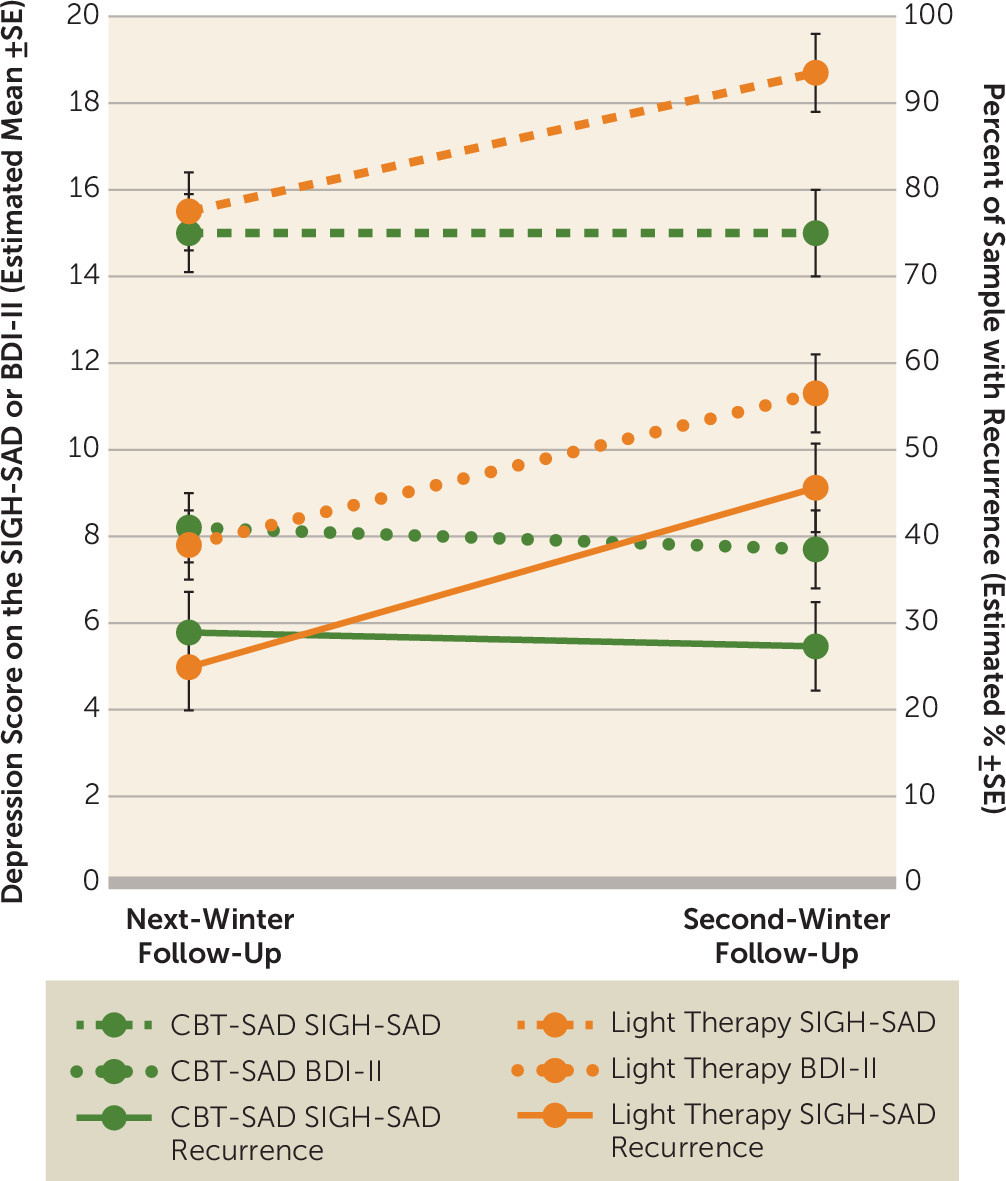

Comparisons between the treatments on next- and second-winter outcomes are shown in

Table 1 and

Table 2, separately for the multiple imputation analyses using the intent-to-treat sample and for the secondary analyses using all available data.

Table 1 presents the dichotomous outcomes of recurrence and remission, and

Table 2 presents the continuous outcomes of SIGH-SAD and BDI-II scores. The main findings are displayed in

Figure 2. There were no statistically significant differences between CBT-SAD and light therapy on any of the outcomes at the next-winter follow-up. There was also no significant difference between treatments in recurrence status based on the October and December tracking calls: 9/73 (12.3%) CBT-SAD participants and 16/76 (21.1%) light therapy participants with tracking call data met major depression criteria (p=0.154).

At the second-winter follow-up, CBT-SAD was statistically superior to light therapy on two out of three dichotomous outcomes and on three out of four continuous outcomes, and this pattern was consistent across analyses using multiple imputation and all available data. On the primary outcome (SIGH-SAD recurrences), CBT-SAD was associated with fewer recurrences at the second winter than light therapy (27.3% compared with 45.6% using imputation; 28.0% compared with 46.5% without imputation). CBT-SAD was also associated with more remissions at the second winter than light therapy using BDI-II criteria (68.3% compared with 44.5% using imputation; 62.7% compared with 44.2% without imputation) but not using SIGH-SAD criteria. Depression scores in CBT-SAD were significantly lower than in light therapy at the second winter on both the SIGH-SAD and the BDI-II. Considering the component scales of the SIGH-SAD separately, HAM-D scores were lower in CBT-SAD than in light therapy at the second winter, but the treatments did not differ on atypical subscale scores.

Given that the treatments did not differ at the next-winter follow-up, but differed on the majority of outcomes at the second-winter follow-up, we conducted exploratory analyses to probe this result. Using SIGH-SAD recurrence status, we examined the association between recurrence status at the next winter and the risk of recurrence at the second winter within each treatment group. CBT-SAD participants without recurrence at the next winter were about five times more likely to not have recurrence at the second winter compared with CBT-SAD participants with recurrence at the next winter (87.5% compared with 15.5%; relative risk=5.12). In contrast, light therapy participants without recurrence at the next winter were only about twice as likely to not have recurrence at the second winter compared with light therapy participants with recurrence at the next winter (63.5% compared with 30.0%; relative risk=1.92). The ratio of relative risk (2.67) differed significantly from one (z=2.38, p=0.017), indicating that although next-winter recurrence status was predictive of second-winter recurrence in both treatments, the relationship was stronger in CBT-SAD than in light therapy. McNemar tests indicated that CBT-SAD participants with recurrence in one, but not both, winters were just as likely to have their recurrence in either winter (p=0.804), whereas light therapy participants with recurrence in only one winter were significantly more likely to recur the second winter (p=0.003). These findings suggest greater durability of a treatment effect in CBT-SAD than light therapy.

Treatment Utilization Over Follow-Up

Descriptive information for ongoing treatment utilization reported at each winter follow-up visit is presented in

Table 3. All participants who reported treatment on the October and/or December tracking telephone calls also reported treatment at the next-winter follow-up. Therefore, the more inclusive next-winter follow-up reports are presented here. A larger proportion of light therapy participants compared with CBT-SAD participants reported any treatment at next winter, but this difference was driven by 34.9% of light therapy participants reporting continued light therapy as instructed (compared with only 7.1% of CBT-SAD participants reporting light therapy). Consequently, the treatment groups did not differ in reports of any new treatment at next winter. At the second winter, the treatments did not differ in the proportions reporting any treatment or any new treatment, but more light therapy participants (30.6%) compared with CBT-SAD participants (13.4%) reported using light therapy. The CBT-SAD and light therapy groups did not differ on psychotherapy or antidepressant medication use at either follow-up. Some cross-over was evident with generally more light therapy participants pursuing psychotherapy than CBT-SAD participants pursuing light therapy.

Logistic and linear regression analyses indicated that differences between CBT-SAD and light therapy at the second winter were not attributable to concurrent treatment(s), in general, or to any new treatment or ongoing light therapy, psychotherapy, or antidepressant medication, specifically. After adjustment for concurrent treatment utilization, CBT-SAD participants continued to have fewer SIGH-SAD recurrences and lower SIGH-SAD, BDI-II, and HAM-D scores at the second winter than light therapy participants. The difference between the CBT-SAD and light therapy groups in BDI-II remissions at the second winter persisted with these adjustments, except when adjusted for ongoing light therapy (see

Table 4).

Discussion

Outcomes for SAD patients initially treated with CBT-SAD or light therapy were comparable at follow-up the next winter but differed two winters after initial treatment. Relative to light therapy, CBT-SAD was associated with fewer depression recurrences using SIGH-SAD criteria, more remissions based on the BDI-II cut-off score, less severe blind interviewer-rated depression on the SIGH-SAD, and less severe patient-rated depression on the BDI-II at the second winter. The superiority of CBT-SAD over light therapy at the second winter persisted after adjustment for any concurrent treatment, in general, and for any new treatment, psychotherapy, or antidepressant medications, specifically. Differences between CBT-SAD and light therapy were somewhat attenuated after adjustment for ongoing light therapy use, which was not unexpected because it is partially confounded with treatment. Nevertheless, BDI-II remission status at the second winter was the only treatment group difference that became nonsignificant after adjusting for ongoing light therapy. Only two of the 11 (18.2%) CBT-SAD participants reporting light therapy at the second winter met BDI-II remission criteria compared with 69.0% of those who reported no light therapy. Interestingly, BDI-II remission at the second winter was also lower in light therapy participants who reported ongoing light therapy (38.5%) than in those who did not (47.5%), but the difference was much smaller than among CBT-SAD participants. Light therapy use may be a marker for nonremission at the second winter, particularly following CBT-SAD.

These follow-up results are consistent with our previous study (

7), except that treatment group differences emerged at the second winter here and were apparent at the next winter in our earlier study (

7). In contrast to our prior work, the present protocol added the October and December telephone calls to prospectively track depression recurrences and re-treatment in the interim between treatment endpoint and the next winter. It is possible that these extra measures and time points created a testing effect in the light therapy group. Treatment differences emerged when participants were “left to their own devices” between the next and second winter follow-ups, as was the case at the single, naturalistic follow-up the next winter in our previous trial (

7).

The following observations are consistent with the interpretation of a testing effect in the light therapy condition at the next winter and also support the interpretation that CBT-SAD had an enduring effect that reduced risk of recurrence after acute treatment compared with light therapy. CBT-SAD participants with a prospective SIGH-SAD recurrence at one follow-up were equally likely to recur in either winter. In contrast, light therapy participants with SIGH-SAD recurrences at one follow-up were significantly more likely to recur at the second winter than the next winter. In addition, the predictive relation between next-winter and second-winter recurrence status was significantly stronger in CBT-SAD than in light therapy. Relative to participants with recurrence at the next winter, participants without recurrence at the next winter were five times more likely to go without recurrence at the second winter in the CBT-SAD group (compared with just two times more likely in the light therapy group).

Reinitiating light therapy each fall/winter season is widely regarded as the most effective means of preventing winter depression recurrence. To our knowledge, clinical trials that have prospectively followed SAD patients treated acutely with light therapy in subsequent winters are limited to our previous study (

7) and the present study. Here, only about one-third of light therapy subjects reported continued light therapy at each follow-up, even though we explicitly prompted continued compliance and made our light boxes available to them the next winter. In our pilot study, only 2/19 (11%) light therapy subjects reported light use the next winter. These results suggest that providing CBT-SAD during acute treatment is a more effective means to reduce risk of recurrence than treating acute SAD with light therapy and instructing patients to resume light use each fall/winter, as practice guidelines recommend. Not resuming light therapy in future winters is problematic, given that light therapy is a palliative treatment that exerts its effects by suppressing symptoms as long as treatment is actively applied.

SAD research has generally focused on achieving acute remission without reference to longer-term outcomes, an approach that does not match the recurrent course of the disorder. These results underscore the importance of including longitudinal follow-up over subsequent winters in SAD clinical trial designs. There is currently no accepted benchmark for defining a SAD treatment failure, but we argue that recurrence is more clinically meaningful than posttreatment nonremission status. By that standard, our data suggest that slightly more than one-quarter of SAD patients initially treated with CBT-SAD and slightly less than one-half of SAD patients initially treated with light therapy would require a next-step treatment strategy within the next 2 years. Therefore, there is room for improvement beyond these two empirically validated SAD treatments, suggesting several future directions. Possible next steps to test empirically include maintenance strategies (e.g., early fall booster sessions focused on using CBT-SAD skills or motivational interviewing around continuing light therapy) and “switch” (i.e., cross-over) or “combine” decision rules. Although our previous study found that solo CBT-SAD had greater benefit the next winter than CBT-SAD combined with light therapy (

7), there might be a subgroup of patients that would benefit from combination treatment. Narrowing the pool to patients who did not respond to first-line solo treatment should help identify those for whom the benefit of combined treatment outweighs the cost.

In conclusion, our previous report found that CBT-SAD and light therapy are comparably effective treatment modalities for acute SAD (

8), but these follow-up data show better outcomes for CBT-SAD than light therapy two winters later. Accordingly, CBT-SAD should be considered as an efficacious SAD treatment and disseminated into practice, particularly if the focus is on recurrence prevention.