T

o the E

ditor: We thank Dr. Plakun for his thoughtful comments on our article. In his correspondence, he brings attention to the relevant concept of differential susceptibility (

1). We appreciate the opportunity to provide further details on some of our findings.

Indeed, we addressed more extensively the differential susceptibility hypothesis in the original version of our manuscript. However, throughout the careful peer-review process, the reviewers correctly pointed out the absence of a true positive environment in our analyses—a central requirement for an accurate assessment of this “for-better-and-for-worse” hypothesis (

2). As the absence of a negative environment could not be considered evidence of a positive environment, and as we were unable to identify in the 1993 Pelotas birth cohort data set a reliable measurement for positive environment, those analyses were removed from the final version of our article. However, if one considers as a proxy for positive (or protective) environment the absence of any childhood maltreatment exposure during the first 11 years of life, we could assess whether the presence of the S allele confers a positive outcome for those experiencing a more protective environment.

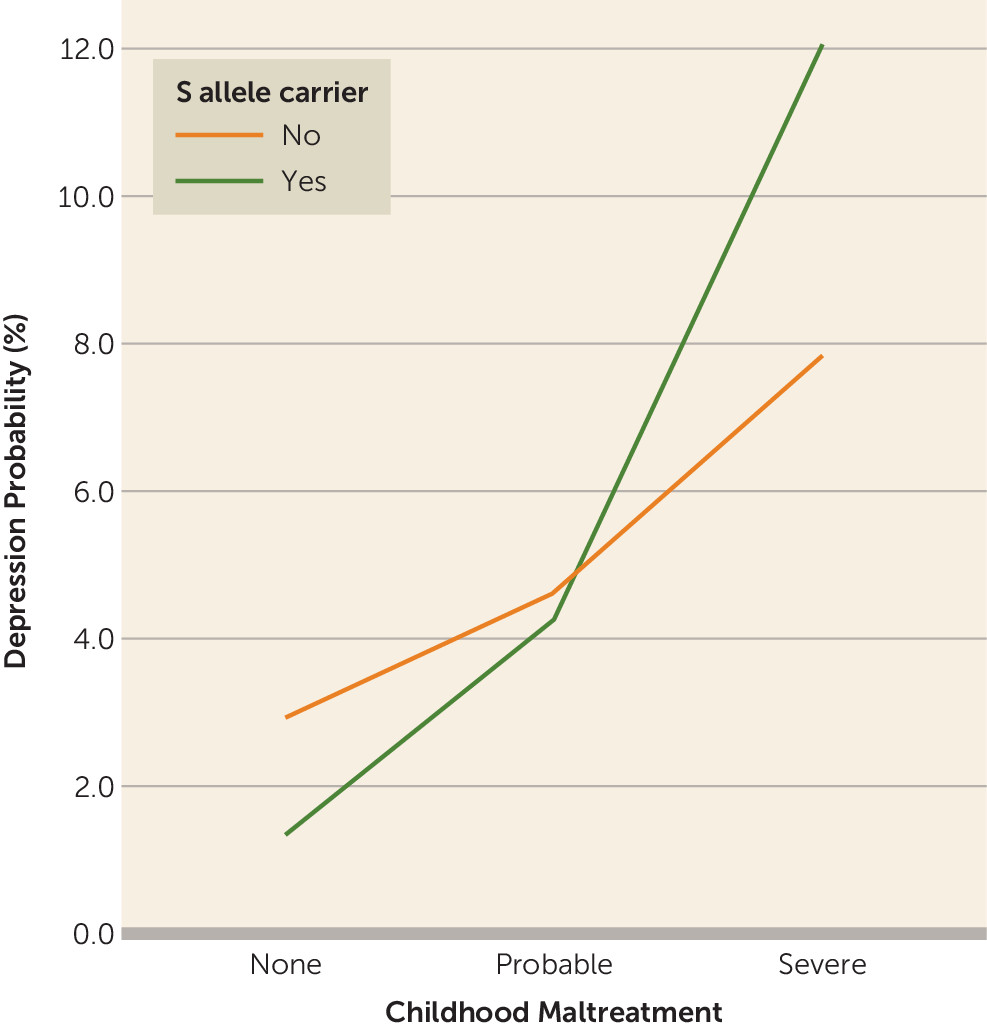

Assessment of the differential susceptibility hypothesis was performed looking for a potential differential role of the genotype among those who reported no exposure to maltreatment. In the additive model, results did not reach statistical significance with regard to the probability of depression (B=−0.45, SE=0.27, Z=−1.67, odds ratio=0.63, p=0.09). When grouped according to a dominant model, those carriers of an S allele had a lower risk for depression after controlling for gender compared with individuals with the LL genotype—from 3.4% to 1.6% for women, and from 2.2% to 1.0% for men (B=−0.78, SE=0.36, Z=−2.17, odds ratio=0.46, p=0.03). In addition, considering the dominant model for the three maltreatment exposure strata,

Figure 1 presents a graphical representation of a disordinal or crossover interaction, which is in accordance with the literature regarding the differential susceptibility hypothesis (

3).

Our results suggest that reactivity differed along the maltreatment spectrum. The probability of depression increases as a function of the number of copies of the S allele and exposure to maltreatment, but it decreases in the group of S allele carriers reporting no experience of maltreatment. These findings concur with the concept of differential susceptibility (

4), according to which the direction of responsiveness depends on the nature of the environmental experience. Following this model, it could be argued that individuals with an increased biological sensitivity to context (in this case, S allele carriers) can benefit from a protective environment (here defined by proxy as the absence of maltreatment).

Unfortunately, up to now, most of our psychiatric research is still focused on the “dark side” of environmental influences. Future studies should also address the “bright side,” investigating the association between positive environments and better mental health outcomes. In this way, we would have more data to confirm or refute the role of the differential susceptibility hypothesis in mental health disorders.