Quetiapine is an atypical antipsychotic that is FDA-approved for the treatment of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and bipolar depression. Quetiapine is an antagonist of the serotonin 5-HT

2 and dopamine D

2 receptors (

19); this profile probably mediates its antipsychotic properties. Quetiapine is also an antagonist of the 5-HT

2A receptor, partial agonist of the 5-HT

1A receptor, and antagonist of the histamine 1 (H

1) receptor and the α

1/α

2-noradrenergic receptors (

19). Quetiapine increases neuropeptide Y levels and lowers corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) (

20). Furthermore, norquetiapine, the main quetiapine metabolite, is a norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (reviewed in reference

21). This pharmacologic profile suggests that quetiapine has specific properties that can be helpful in the treatment of PTSD, particularly in re-experiencing and hyperarousal symptoms, as well as associated depressive and anxiety symptoms.

Results

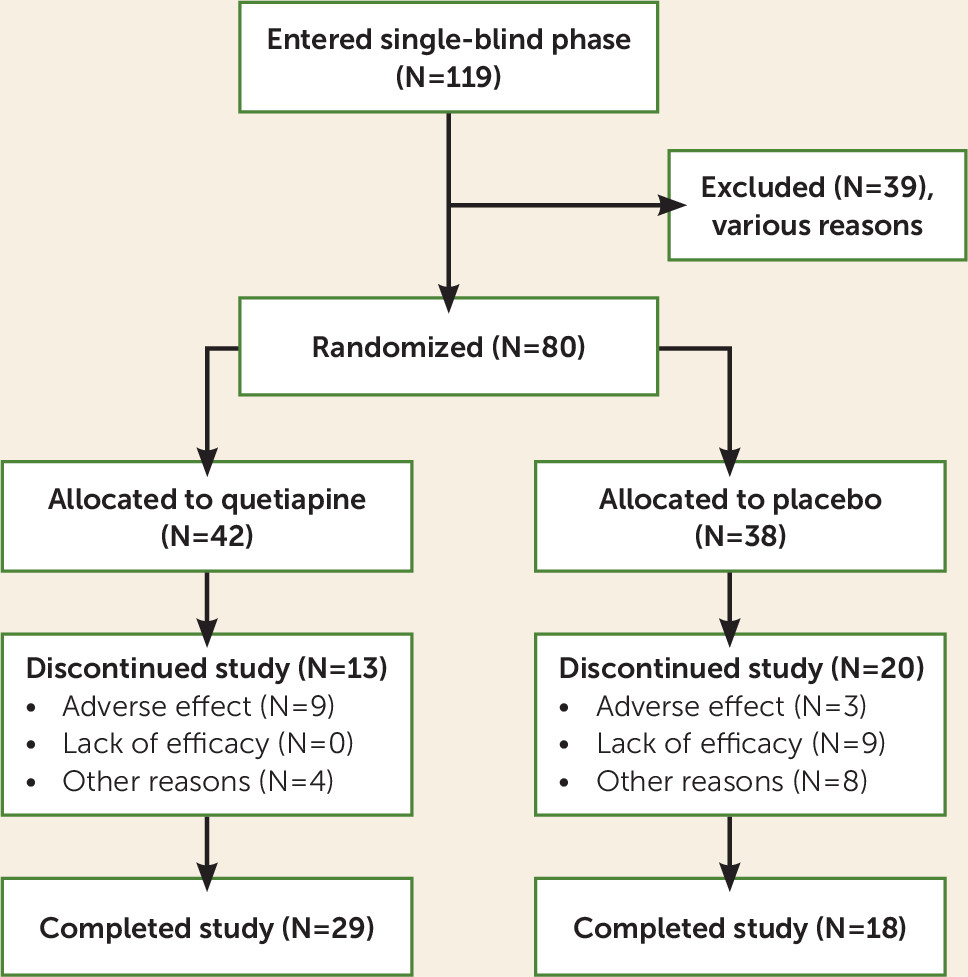

Of the screened patients, 119 entered the single-blind phase; 39 dropped out for various reasons, and 80 (40 at each site) were randomly assigned to quetiapine or placebo (see

Figure 1). Six patients required rescue medication during the first 2 weeks of double-blind treatment, but none were excluded because of this. Patient demographic characteristics are shown in

Table 1. Forty-two subjects were randomly assigned to quetiapine and 38 to placebo. Thirteen patients (31%) dropped out of the quetiapine group, and 20 patients (53%) dropped out of the placebo group (Fisher’s exact test, p=0.07). The mean age of the participants was 52 years, with no significant difference between the quetiapine and placebo groups. The patients in the quetiapine group had slightly more education (mean=14.2 years, SD=2.4) than those in the placebo group (mean=13.07 years, SD=2.3) (t=–2.13, df=77.474, p=0.04). The majority of the patients were male combat veterans. There was no difference in the percentage of males between groups (see

Table 1). Race distributions were also similar in the two groups. Twenty-one of the patients were African American, 17 were Native American, and 42 were Caucasian. It should be noted that more Hispanic and Native American patients were seen at the New Mexico site and more African-American patients were seen at the Charleston site.

Efficacy Results

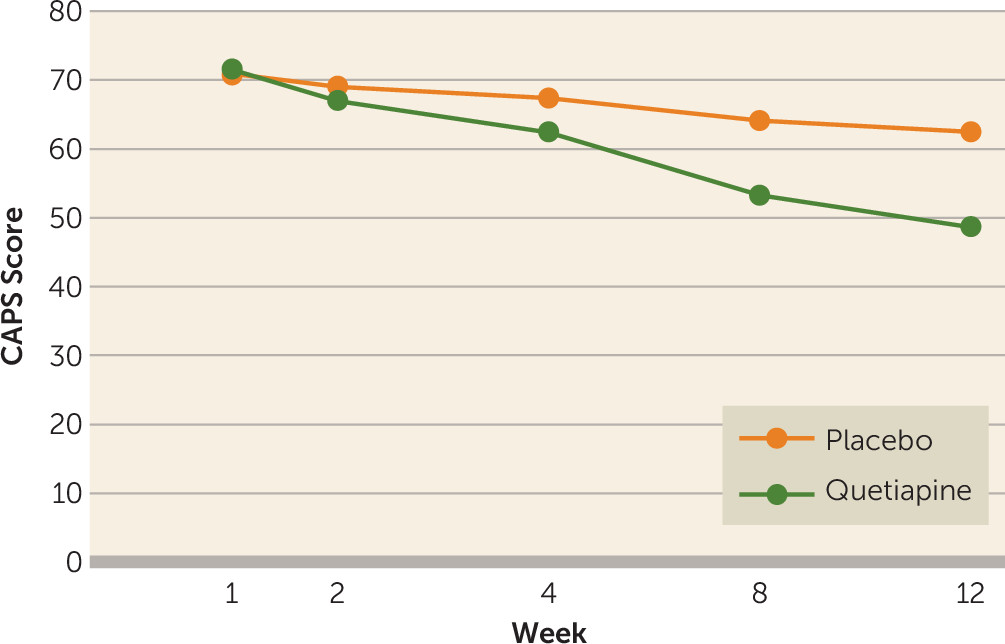

The main efficacy measures were conducted at baseline and at weeks 2, 4, 8, and 12. The mean total baseline CAPS scores were similar in the quetiapine and placebo groups, 75 (SD=16) versus 71 (SD=12) (t=−0.76, p=0.45). However, DSM-IV cluster B scores (re-experiencing) were higher in the quetiapine group (mean=21, SD=7) than in the placebo group (mean=17, SD=15) (t=2.4, p=0.02). For this reason, the main outcome analysis was ANCOVA utilizing the baseline CAPS score as a covariate, drug as a fixed factor, and visit as a repeated factor. We found a significant effect of the interaction of visit and treatment condition (F=2.88, df=4, 240, p=0.03), indicating that the quetiapine group had a greater drop in total CAPS score than the placebo group (see

Figure 2). A logistic regression of the binary variable for dropouts was not significant (p=0.50), which is consistent with dropouts being “completely at random” and not related to the subjects’ last CAPS value, nor were dropouts related to which treatment group the subject was in (p=0.42). An intent-to-treat-analysis of the full repeated measures (ANCOVA) model gave a significant treatment-by-visit interaction (F=2.94, df=4, 312, p=0.02).

The results of the secondary outcome measures were as follows. The quetiapine group had greater improvements than the placebo group on the CAPS re-experiencing subscale (F=12.7, df=1, 246, p=0.0004) and the hyperarousal subscale (F=7.43, df=1, 246, p=0.007) but not on the avoidance/numbing subscale (F=2.28, df=1, 246, p=0.13). Efficacy results are shown in

Table 2.

We compared the Davidson Trauma Scale scores of the two groups with a mixed-model ANOVA with drug as a fixed factor and visit as a repeated factor. We found greater improvement in the quetiapine group (F=4.89, df=1, 246, p=0.03). A similar analysis for the CGI severity rating revealed greater improvement in the quetiapine group (F=3.35, df=4, 240, p=0.01). The CGI improvement scores were lower (better) at week 12 for quetiapine than for placebo (t=2.98, df=63, p<0.01) (see

Table 2).

We also found a significant treatment-by-visit interaction for the HAM-D (F=2.88, df=4, 240, p=0.02) and the HAM-A (F=6.76, df=1, 63, p=0.01), indicating greater improvement in depression and anxiety scores in the quetiapine group (see

Table 2).

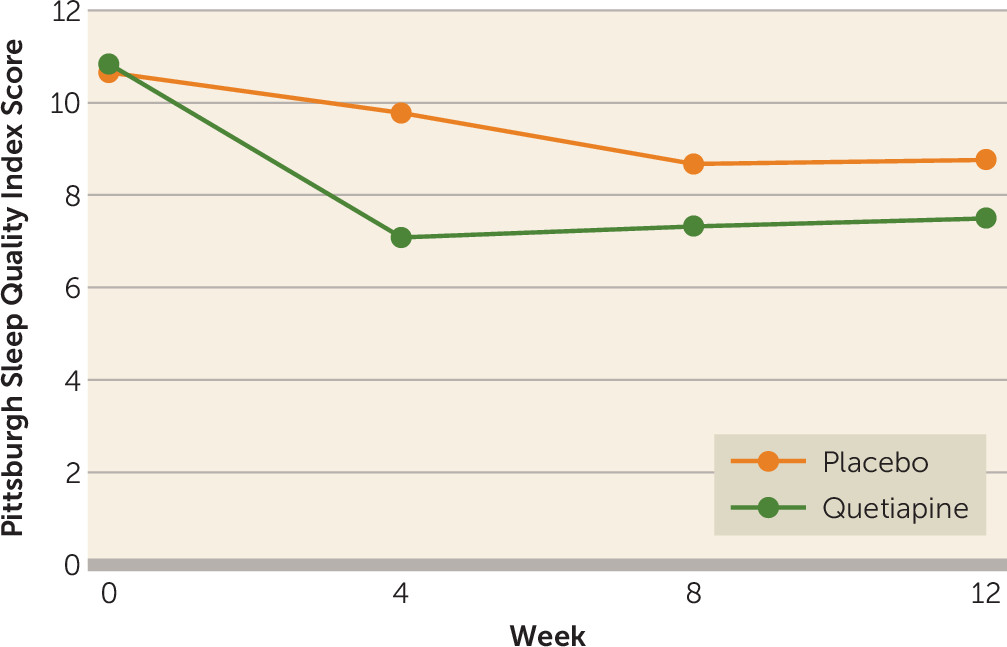

The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index was administered at baseline and weeks 4, 8, and 12. We found a treatment effect (F=6.22, df=1, 77, p<0.05), but the visit-by-treatment interaction was nonsignificant (F=1.49, df=3, 1175, p=0.20) (see

Figure 3).

The PANSS was administered at weeks 0 and 12. The analysis of the PANSS global psychopathology and positive symptom subscales showed significant treatment-by-visit interactions (global: F=8.51, df=1, 63, p=0.005; positive symptoms: F=10.39, 4, 240, p=0.002, respectively), indicating greater improvement in the quetiapine group. However, we did not find a significant treatment-by-visit interaction for the negative symptom subscale (F=1.99, df=1, 63, p=0.16).

Safety Reports

The adverse events were generally mild and consistent with the known safety profile of quetiapine. The most common side effects in the quetiapine group were dry mouth (15.8%), somnolence (13.4%), and sedation (7.4%). Nine patients dropped out of the quetiapine group because of adverse effects, while three dropped out of the placebo group for that reason. There were no significant differences in weight, pulse, or blood pressure measurements between the quetiapine-treated patients and the placebo group (see

Table 3). The safety scales were administered at weeks 0 and 12. There were no significant differences on these scales between quetiapine and placebo (see

Table 3).

Dose

The final dose range of quetiapine for all patients who had at least one efficacy assessment visit (N=41) was 50 to 800 mg daily. The average quetiapine dose was 258 mg daily. The final dose range of placebo in patients who had at least one efficacy assessment (N=38) was also 50 to 800 mg daily with an average dose of 463 mg daily. Since dose was considered an ordinal outcome and unlikely to be normally distributed, a nonparametric test (chi-square analysis) was utilized to compare doses of quetiapine and placebo. Based on this analysis, the dose of placebo was significantly higher than the quetiapine dose (χ

2=13.75, df=1, p=0.0002). No patients dropped out of the quetiapine group because of lack of efficacy, and nine patients dropped out of the placebo group for that reason (see

Figure 1).

Discussion

The primary outcome measure, the total CAPS score, demonstrated significantly greater improvement in the quetiapine-treated group than in the placebo group. That the dose of placebo was almost twice that of quetiapine confirms the significance of this finding, implying that clinicians continued to titrate the placebo to a higher dose due to lack of efficacy. Furthermore, while there were no dropouts in the quetiapine group due to lack of efficacy, nine patients dropped out of the placebo group for that reason. These results are remarkable, given the severity, chronicity, and difficult-to-treat nature of this population.

Total Davidson Trauma Scale scores and as hypothesized, CAPS re-experiencing and hyperarousal subscale scores, demonstrated significant improvement with quetiapine versus placebo. In contrast, and consistent with a review of atypicals in PTSD (

17), scores on the CAPS avoidance/numbing subscale and the PANSS negative symptom subscale did not differ from those of the placebo group. In addition, the CGI improvement and severity, HAM-A, HAM-D, and PANSS positive symptom and general psychopathology subscale scores showed improvement in the active medication group. Of particular interest is the improvement in depression ratings (HAM-D), since the frequency of comorbid depression in PTSD is common and no antidepressant medication was used.

It is not surprising that in this study neither negative or avoidance symptoms responded during this relatively short-term trial. It may take longer for these symptoms to improve as patients adopt more healthy behaviors with improvement in re-experiencing and hyperarousal symptoms. Consistent with our findings, in a review of PTSD treatment with atypicals, re-experiencing and hyperarousal symptoms responded better to these medications (

17).

A surprising finding was the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index results. We hypothesized improved sleep measures with quetiapine. We did find a treatment effect, but the treatment-by-visit interaction was not significant. The graph in

Figure 3 suggests better sleep response in the quetiapine group by week 4 (visit 5) that was lost at subsequent visits. This needs to be further investigated.

This study was consistent with our earlier open trial and with several case reports and open trials of quetiapine in PTSD (

22), reviewed by Ahearn et al. (

17). These studies have largely investigated the use of quetiapine as an adjunctive therapy. To our knowledge, the present study is the first double-blind placebo-controlled trial of quetiapine as monotherapy in PTSD.

Interestingly, in spite of the paucity of evidence of quetiapine’s usefulness in PTSD, this medication and other atypicals are widely used to treat this condition. Studies in VA populations have shown high rates of atypical prescriptions for PTSD. Bauer and colleagues (

28) analyzed data on 732,085 veterans with PTSD treated between 2003 and 2010 and found that 27.6% of them received an atypical for this condition. Hermes et al. conducted a survey of 2,613 VA providers and found that 13% of quetiapine prescriptions were given for a sole PTSD diagnosis (

29). Furthermore, a retrospective chart review found that quetiapine was as effective as prazosin in treating nightmares, but patients taking quetiapine were more likely to discontinue medication due to side effects (

24).

Other studies with quetiapine have also demonstrated a potentially unique effect in depression, particularly in patients with anxious features (

30). In fact, quetiapine has FDA approval for treatment of bipolar depression. Moreover, there is increasing interest in treating comorbid psychiatric symptoms in PTSD (

31), including psychotic symptoms (

22), nightmares, (

32), and depression, in addition to other comorbidities. The depressive symptoms are often secondary to PTSD or overlap with specific PTSD symptoms, e.g., sleep disturbances or anhedonia. Our findings indicate that quetiapine as a single agent significantly improved depressive symptoms in PTSD patients.

Quetiapine has a unique pharmacological profile, partly mediated by its metabolite norquetiapine, with a combination of effects on the serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine systems (

19,

21). There is also evidence that quetiapine increases neuropeptide Y and lowers CRH in the CSF. This unique profile may explain the beneficial effects of quetiapine on PTSD, depression, and anxiety symptoms. The antihistaminergic effects may be desirable in this population to facilitate sleep. The α

1-adrenergic antagonist properties may contribute to reduction in nightmares and associated sleep difficulties, as suggested by studies with prazosin, which is an α

1-adrenergic antagonist (

32). D

2 receptor antagonist effects may affect a variety of symptoms, including intrusive memories, flashbacks, and comorbid psychotic symptoms. The higher ratio of HT

2 receptor effects to D

2 effects may contribute to the low extrapyramidal side effect profile. The relatively lower D

2 receptor antagonist effects may also contribute to a lack of sustained prolactin elevation and associated side effects with quetiapine (

33). Moreover, the rapid dissociation of quetiapine from the dopamine receptor (analogous to clozapine) may be sufficient to contribute to efficacy while yielding fewer extrapyramidal or prolactin-related side effects.

In summary, current practice guidelines support the use of atypical antipsychotics as one of several medication options in patients who are refractory or only partially responsive to antidepressants and psychotherapy, but they also note that data on use of these agents are limited (

25,

34). Our findings suggest that quetiapine as a single agent is effective in the treatment of PTSD and associated depression and anxiety symptoms. The level of improvement observed with quetiapine suggests it may be superior for the treatment of PTSD over other antipsychotics, such as risperidone, which did not improve global PTSD symptoms in a large study with veterans (

18).

Quetiapine was well tolerated. The main side effect was somnolence, which was not a significant problem, as no subjects discontinued the study on its account. There were no differences in vital signs, weight, or extrapyramidal symptoms between groups. However, a word of caution is in order because of increasing concerns about metabolic side effects of the new-generation antipsychotics (

35). Diabetes mellitus was not an exclusion criterion; in fact, six subjects (15.8%) in the placebo group had diabetes and one (2.6%) had a history of hyperglycemia. In the quetiapine group, 10 subjects (23.8%) had a diabetes diagnosis and one (2.4%) had a history of hyperglycemia. Only one of the diabetic patients was not receiving diabetes treatment. Thirty-one patients were taking statins, and four were receiving gemfibrozil. Unfortunately, glucose and hemoglobin A

1c were not monitored longitudinally, but the fact that we did not find weight gain in the quetiapine group indicates this medication was a safe short-term treatment. When quetiapine is used, weight, lipids, and hemoglobin A

1c should be monitored closely. If metabolic changes are detected, the quetiapine dose should be lowered or switching to another medication should be considered.

Although improved, the patients receiving quetiapine remained symptomatic, with a mean CAPS score around 54. Therefore, in a clinical setting, additional psychopharmacological or psychotherapeutic interventions would need to be considered.

These initial results are encouraging because chronic military PTSD is often refractory to a variety of treatments, but the findings need replication. We hope that more studies will be conducted to better define the role of quetiapine and other atypical antipsychotics in patients suffering from PTSD. We would like to point out that we finished the study in 2008, but we feel our findings continue to be relevant since atypicals are often prescribed in PTSD and there are still relatively few studies testing their efficacy in this condition.