The publication of DSM-5 (

1) saw the recategorization of adjustment disorder as a trauma- and stressor-related disorder in recognition that a stressful event is a necessary (although not sufficient) condition for the development of the disorder. Despite the reconceptualization, the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria did not change from DSM-IV, as it was argued that so little research had been undertaken on adjustment disorder that any such changes would be based on too limited evidence (

2). Adjustment disorder represents one of the most poorly researched psychiatric diagnoses, with little empirical understanding of its phenomenology, relationship to other disorders, or course (

2–

5). This is a worrying situation given the frequency with which it is used in clinical practice (

2).

Prevalence of Adjustment Disorder

Adjustment disorder has not been included in national mental health surveys, and thus population prevalence rates are unknown. The exception to this was the European Outcomes of Depression International Network study, which reported a prevalence rate of 0.5% using DSM-IV criteria but which restricted adjustment disorder to the depressed mood subtype only (

6,

7). Prevalence studies in populations exposed to specific stressors are generally of poor methodological design, such as small sample size (

8), medical chart review (

9), or verbal autopsy review (

10). However, more recent studies have utilized stronger methodological designs. For example, a meta-analysis of cancer patients based on 27 articles reported a pooled adjustment disorder prevalence rate of 19% (

11). Similar rates have been reported within consultant-liaison psychiatry inpatients (

12), but lower rates have also been reported in other settings such as primary care (

13). To our knowledge, no study to date has reported the prevalence of adjustment disorder following a traumatic stressor (defined as meeting DSM-5 definition of traumatic stressor (

1, p. 274).

Method

Participants

The data utilized in this study were from a large cohort study of injury survivors, the Australian Injury Vulnerability Study. Detailed methods and information on the study are described elsewhere (

14). Individuals with injury admissions to four level 1 trauma centers in Australia were recruited from April 2004 to February 2006. Participants were included in the study if they were between 16 and 70 years old, proficient in English, and required hospitalization for greater than 24 hours. Patients were excluded from the study if they were actively suicidal or psychotic or had a moderate to severe traumatic brain injury. Patients were selected using an automated random selection procedure that was stratified by length of stay to ensure that the likelihood of being selected for participation in the study was not biased by long-stay patients. The study was approved by relevant ethics committees, and written informed consent was obtained for all participants.

Baseline data were collected prior to discharge from the hospital, which was on average 7.20 days (SD=9.07) after injury, and follow-up data were collected at 3 months and 12 months after injury. A total of 1,049 participants completed the baseline assessment, 944 completed the 3-month follow-up, and 826 completed the 12-month follow-up. Individuals who elected not to participate in the study did not differ from those who participated with regard to age, gender, length of hospital admission, or injury severity. Those lost to follow-up at 3 months or 12 months did not differ on demographic variables except age, with those lost to follow-up being younger at admission (3 months: 35.86 years old [SD=13.21] compared with 38.75 years old [SD=13.71], t=2.27, df=1033, p<0.05; 12 months: 35.59 years old [SD=12.77] compared with 39.26 years old [SD=13.24], t=3.71, df=1033, p<0.001).

Measures

Three- and 12-month adjustment disorder.

There is no recognized gold standard DSM-5 adjustment disorder diagnostic instrument (

2). Therefore, we assessed adjustment disorder using a number of different measures that included the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS [

15]), the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview 5.5 (

16), and the World Health Organization Quality of Life-BREF (

17). The operationalization of adjustment disorder is presented in

Table 1.

The CAPS is a structured clinical interview widely used for diagnosing posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Interviews were digitally recorded, and 5% of all CAPS interviews were assessed by a blind, independent assessor to test interrater reliability. Overall, the diagnostic consistency on a PTSD diagnosis at 3 months was 0.98, and at 12 months it was 1.0.

The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview 5.5 is based on the DSM-IV/ICD-10 classifications of mental illness (

16). Modules administered included major depressive episode, PTSD (prior to injury), generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, panic disorder, agoraphobia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and a substance use disorder. Diagnostic consistency, using previously described methodology, for all diagnoses at 3 months was 0.99, and it was 1.0 at 12 months.

The World Health Organization Quality of Life-BREF psychological domain is an 8-item scale that assesses aspects of distress, such as feelings of despair, low mood, anxiety and depression, failure to enjoy life, and absence of meaning in life. Australian population threshold score was used to identify high distress (

18).

Disability.

The impact of adjustment disorder (diagnosis and individual symptoms) on disability was assessed using the 12-item World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule II (

19), which was administered at 3 and 12 months postinjury. Higher scores are associated with higher disability (

20).

Quality of life.

The impact of adjustment disorder on quality of life was assessed using three domains from the World Health Organization Quality of Life-BREF (social, environmental, and physical). It is noteworthy that the fourth domain (psychological) was used to construct the diagnosis and thus not included in the analyses that examined the disorder’s impact on quality of life. High scores indicated higher quality of life (

21).

Anxiety and depression.

The presence and severity of anxiety and depressive symptoms was assessed using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (

22). This self-report questionnaire is suitable for use in injury populations, since it does not measure the somatic symptoms of affective or anxiety disturbance.

Data Analysis

The 3- and 12-month prevalence of adjustment disorder was assessed using frequency data. While recognizing that assessing adjustment disorder at 12 months postinjury contravenes the DSM-5 adjustment disorder time criteria (criterion E), we wanted to assess the relevance of the diagnosis over the long-term (and thus for the 12-month prevalence rates, the time criterion was excluded).

To assess the severity of adjustment disorder compared with other disorders, we ran a three-group multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) comparing those with an adjustment disorder, those with another psychiatric disorder, and those without any disorder on measures of quality of life, disability, and anxiety and depressive symptoms. These analyses were run using the 3-month data. Assumptions required for MANOVA are presented in the data supplement accompanying the online version of this article.

To examine adjustment disorder trajectory over time, we conducted three binomial logistic regressions. The first was to identify whether adjustment disorder at 3 months (compared with no disorder) increased risk for another psychiatric disorder at 12 months. The second was to identify whether adjustment disorder at 3 months (compared with no disorder) increased risk for adjustment disorder at 12 months. The third was to identify whether adjustment disorder at 3 months (compared with no disorder) increased risk for suicidality at 12 months. All logistic regressions controlled for age, gender, marital status, and injury severity score.

A latent-profile analysis was conducted to assess whether there were distinct subtypes within the diagnosis. A latent-profile analysis is a person-centered analysis that is used to find clusters of individuals with similar patterns of responses to indicator measures (

23). For these analyses, we used the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale scores. All analyses were completed in Mplus version 7.11 (

24). The decision on the preferred number of classes was based on model-fit criteria, interpretability, and parsimony (see the

online data supplement for information on fit criteria). If our data were consistent with the subtypes identified in DSM-5, we would expect to see a high anxiety/low depression class, a high depression/low anxiety class, and a high depression/high anxiety class.

Following this, we examined which symptoms were particularly important to the diagnosis of adjustment disorder and which were particularly disabling. Binomial logistic regression was used to identify which 3-month symptoms predicted a 3-month diagnosis of adjustment disorder and which predicted 3-month disability (World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0). A Holm-Bonferonni sequential correction was applied to correct for family-wise error rates (

25).

Discussion

Since its introduction into DSM nomenclature, adjustment disorder has been a relatively understudied and controversial disorder. This large, multisite cohort study of adjustment disorder goes some ways toward addressing important questions about the disorder.

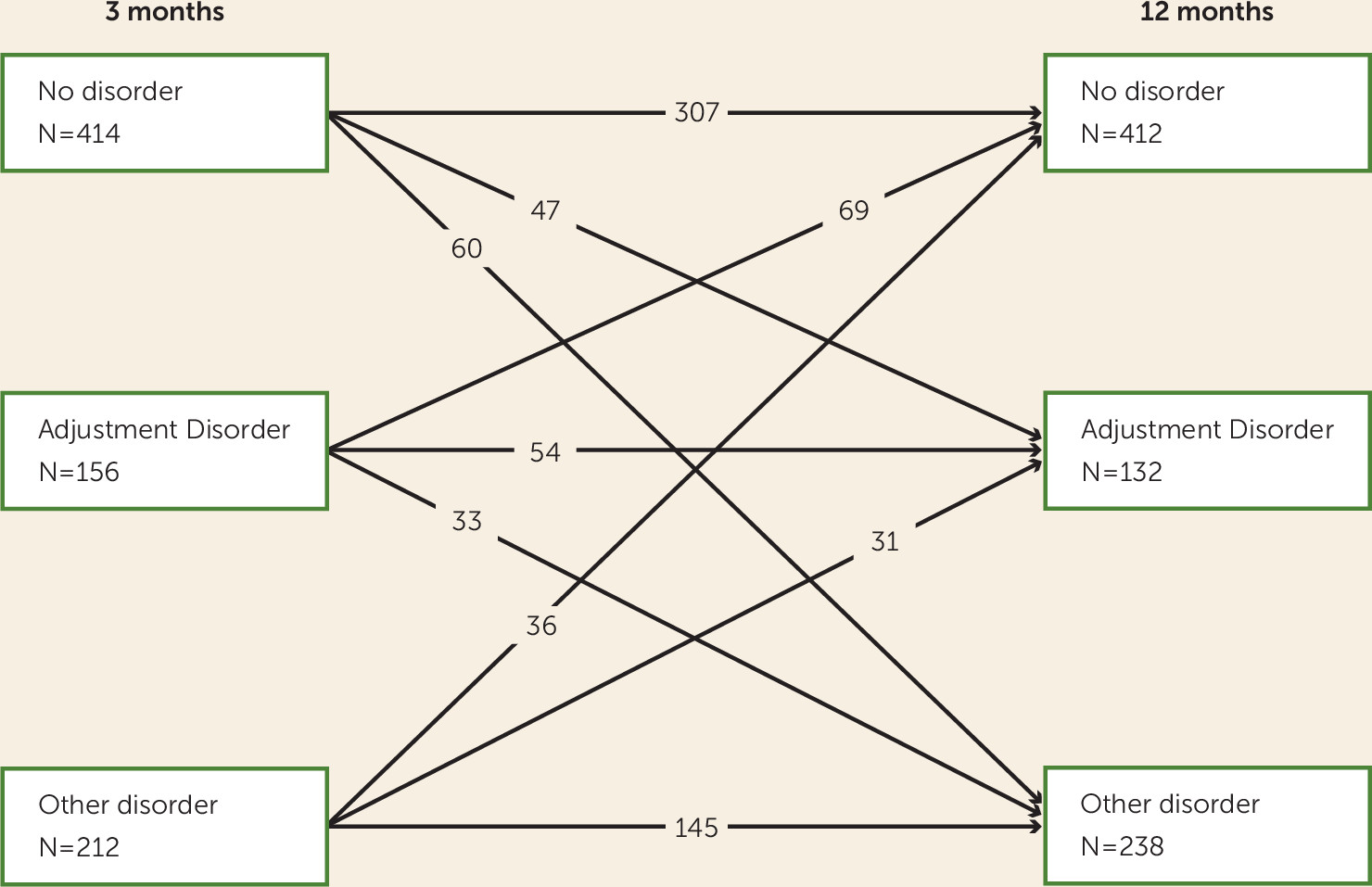

The prevalence rate of adjustment disorder made it one of the most frequently diagnosed psychiatric disorders in this sample (see Bryant et al. [

14] for other prevalence rates from this sample). Our study extends most other adjustment disorder research by allowing a 3-month period between the injury event and assessment, which allowed for acute but transient distress symptoms to dissipate. Adjustment disorder was a chronic condition for approximately one-third of those with the disorder at 3 months. This is an important finding given the chronic specifier was present in DSM-IV but removed in DSM-5, and it suggests that future reviews of diagnostic criteria should take into consideration that adjustment disorder is not a transient disorder for some people. Future studies are needed to investigate chronic adjustment disorder in more detail.

Our study also highlights that adjustment disorder is not a stable condition, with the majority of patients with the disorder at 12 months not having the diagnosis at 3 months, and two-thirds of those who had the disorder at 3 months no longer had the diagnosis at 12 months. This fluctuating diagnostic status is consistent with studies that report the changing course of other psychiatric disorders over time (

28). The development of adjustment disorder after the 3-month time points may be associated with the consequences of the injury that develop in the ensuing months, such as legal issues or occupational impairment. This finding challenges the current adjustment disorder criterion A, which requires the disorder to commence within 3 months of the stressor and suggests that future revisions consider the possibility that patients may develop difficulties adjusting to the consequences of an event at a later point in time.

In addition to providing support for elevating adjustment disorder to the trauma- and stressor-related disorders chapter in DSM-5, our findings provide some support for the ICD-11 proposed criteria for adjustment disorder, which view adjustment disorder as sitting on the PTSD continuum (

29). In our study, intrusive memory was the symptom that was most likely to be associated with a diagnosis of adjustment disorder, and a number of PTSD criterion E symptoms were significantly associated with either adjustment disorder or high levels of disability (e.g., poor concentration, disturbed sleep, and irritability/anger). This is consistent with the view that adjustment disorder is (in part) a subthreshold PTSD-like disorder (

30). However, all these symptoms are also associated with many other psychiatric disorders—concentration difficulties (

1), poor sleep (

31), intrusive memories (

32,

33), and anger (

34)—and as such it is important to consider adjustment disorder in its wider context.

Our initial investigations would suggest that the DSM-5 adjustment disorder sits on a continuum between no disorder and other psychiatric disorders. In our study, compared with other psychiatric disorders, adjustment disorder was associated with significantly lower levels of disability/anxiety/depression symptoms and higher levels of quality of life. This finding appears to be in contrast to other studies that suggest that adjustment disorder and other psychiatric disorders are indistinguishable in terms of symptom severity (

7), but it is consistent with results reported in a recent study (

13). However, our data also point to adjustment disorder as a gateway disorder to other, more severe disorders. This suggests that the disorder could be an excellent target for brief interventions to alter the trajectory into severe disorder.

The latent-profile analysis showed that in general a mixed anxiety and depression profile was most common. We did not find classes distinguished by high anxiety/low depression or high depression/low anxiety that we would expect to see if the DSM-5 subtypes existed. This leads us to suggest that subtyping in adjustment disorder is unnecessary. While recognizing that subtypes are often used to guide the focus of treatment, our findings suggest that targeting PTSD, anxiety, and depression symptoms would be more appropriate than limiting intervention to a narrow subtype.

Our findings may have implications for the assessment and diagnosis of adjustment disorder under DSM. We would argue that a clear list of symptoms should be provided to help address the diagnostic vagueness of DSM-5. Given that the current intent of the DSM-5 diagnosis of adjustment disorder is to identify people who have limited but disabling symptoms, our findings suggest that important symptoms to include in this list are intrusive memories, sleep disturbance, anger/irritability, and concentration difficulties. However, further research is required to further refine the diagnostic criteria for the disorder.

Despite the strong methodological design of our study compared with most adjustment disorder studies, some limitations should be noted. Because of the lack of instruments designed to assess the DSM-5 criteria for adjustment disorder, we compiled a measure from existing measures, and the resulting diagnosis has no reliability or validity information. There are many aspects of the DSM-5 adjustment disorder diagnosis that make operationalization difficult, and these limitations have been frequently discussed (

2,

4). Of particular relevance to our study was the issue surrounding what defines a “stressor,” as well as the “consequences of the stressor.” In this study, we defined the stressor as the injury event. We did not assess the consequences of the stressor directly, which may have implications for our comments about chronic adjustment disorder and means that we cannot comment on whether it was the initial injury or the consequences of the injury (such as pain) that was the trigger stressor. Second, it was difficult to operationalize “normal bereavement” given cultural and contextual norms, and as such we excluded a small group of individuals who were bereaved (N=10). This may affect the generalizability of our findings. Similarly, because DSM-5 does not define “a disturbance in conduct,” our ability to capture this aspect of the diagnosis was limited. Finally, it should be recognized that the stressor event in our study was a relatively homogenous, traumatic event (i.e., severe injury), and the degree to which our findings generalize to nontraumatic events or other traumatic events is unknown. Future studies should also consider that an individual’s response to a stressor may vary across cultures, and this should be considered as part of the stressor-response evaluation.

Adjustment disorder now sits alongside PTSD in the trauma- and stressor-related disorders chapter in DSM-5. Many of our findings provide support for the inclusion of adjustment disorder in this chapter. This study adds to the limited research evidence on adjustment disorder by demonstrating that the diagnosis identifies people who following a stressor experience distress/functioning impairment and who are at risk for developing more severe disorders. However, it challenges the current diagnosis by finding that 1) many people develop the disorder beyond the initial 3 months after the stressor and 2) it does not present with distinct anxiety or depressive symptoms but rather mixed features, with PTSD symptoms playing an important role. Considering the frequency with which this diagnosis is used by clinicians, it is imperative that more structured research is conducted so that robust diagnostic criteria can be established.