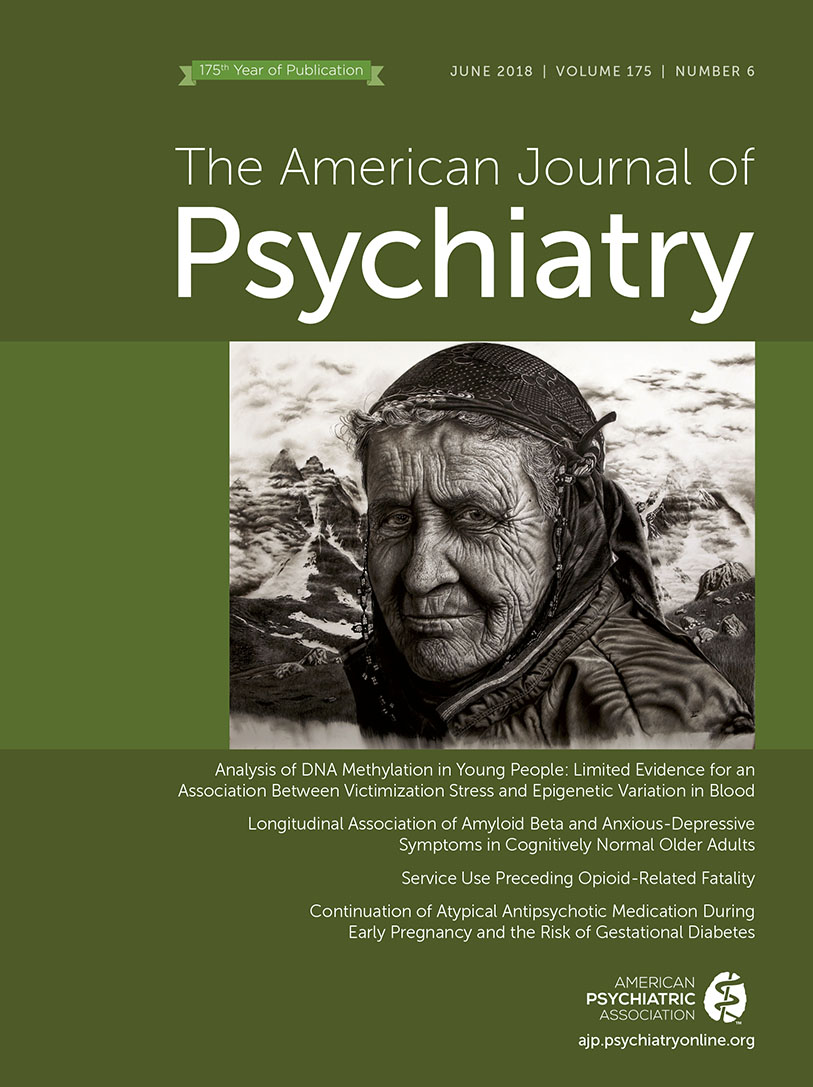

This report describes a 19-year-old male patient with dissociative identity disorder who has an extraordinary skill in drawing. After carefully observing people, objects, or their photograph, he later creates hyperrealistic charcoal drawings of them entirely from memory. Remaining partly amnestic, he produces these pictures during a trance, that is, in control of an alternate personality state. He daydreams about unrelated themes while “his hand” keeps drawing. Such episodes follow an “appetite-like” urge to draw. Withdrawing to his studio, he suspends daily activities (e.g., skipping meals), enters an apparent stupor, and the “child inside” takes control. He does not experience these drawings as produced by himself. As an artist “still in development,” he does not sign them yet by name; he uses a cipher instead.

According to DSM-5, dissociation is characterized by a disruption in usually integrated psychological capacities such as perception, consciousness, attention, memory, and sensorimotor functions. While it serves to cope with unbearable developmental stress, genetic predisposition for a special skill may “benefit” from such dissociation by finding a niche of “freedom” in which to flourish. Dissociated action tendencies (including sensorimotor phenomena) can be adopted and gradually dominated by discrete behavioral states (

1) or parallel-distinct mental structures (

2) in dissociative identity disorder to obtain a sense of self and agency, and even a narrative. Greater suppression of the default mode network during a state of mind-wandering trance (absorbed in vivid imaginations and memories) may be associated with better performance on an otherwise attention-demanding task (

3), as it is a mechanism also involved with automatic processing (

4).

The patient reported amnestic gaps in daily life, such as finding himself in a new place without having any idea how he arrived there. Others have observed him talking to himself occasionally. He also reported childhood-onset visual hallucinations and illusions, such as seeing the image of a skeleton or of an unfamiliar person. He used to laugh inappropriately or behave in a childish-playful manner. He frequently failed to keep up with personal responsibilities. He lacked close friends among peers. He was previously diagnosed as having atypical pervasive developmental disorder, Asperger’s syndrome, or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

He started to perceive another child “inside” when he was 9 or 10 years old. Because he was frightened by strange internal voices, his mother let him wear an amulet as protection against supernatural jinnies. Having the same voice as his, this “inner” child made very persuasive demands that he felt obliged to carry out (e.g., “screaming when bored” regardless of the social situation). The “child inside” refused the existence of time (detemporalization). Both he and the child perceived themselves as 6–8 years old. His childish manners manifested in particular when he experienced interpersonal conflict. Nevertheless, he enjoyed conversations with adult acquaintances who were like-minded.

He was the oldest of three siblings, and he was exposed to physical and emotional maltreatment and witnessed domestic violence from early childhood. He was separated from his parents for 4 months when he was 4 years old and experienced a physical assault by older children when he was 6. He had oppositional behavior in primary school (e.g., violating classroom rules, leaving the school building without permission) because he did not like the “meaninglessly monotonous order.” Labeled as a “nut,” he became an outsider in school and was bullied by his peers. His artistic talent drew attention during painting lectures when he was 12. Despite his rebellious attitude against the “system” (

5), he succeeded in graduating from an art secondary school. Because he believed that school killed creativity, he declined to attend a college. His mother’s uncle and a cousin were also talented in painting. His paternal grandmother wrote epics and poems before she became chronically psychotic. His parents divorced when he was 16.

He was talkative during interviews, and he responded to jokes with a childish joy. He had no affective blunting, formal thought disorder, disorganized behavior, or delusions. His IQ was in the normal range. He had an elevated score (6.3/10) on the Adolescent Dissociative Experiences Scale, and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Dissociative Disorders confirmed the diagnosis of dissociative identity disorder. He declined proposed psychiatric treatment, as he and his internal doppelgänger enjoyed their productive comradeship, which made social isolation and loneliness rather negligible. Moreover, both considered the drawing sessions relieving. Nevertheless, he was eager to share his experiences “to serve the science.”