Sixty years of treatment research for depression has produced advances in pharmacotherapy, refinements in the delivery of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), newer neuromodulation treatments, and the development of time-limited, symptom-targeted, manualized psychotherapies. Clinicians now have a broad range of treatment options to control or eliminate symptoms, restore function, and enhance longer-term outcomes with continuation and maintenance treatments (

1–

3) for patients with mood disorders.

Consequently, clinical practice guidelines for depression (

1,

4–

7) now recognize four possible initial management strategies: medication, psychotherapy, their combination, and active surveillance (watchful waiting). The choice among these strategies logically depends on the clinical context (e.g., symptom severity, clinical acuity, concomitant conditions, and social support) as well as the patient’s treatment goals.

Whatever the treatment chosen, the goals of treatment are total and sustained symptom relief (or at least optimal symptom control, if sustained remission is elusive); restoration of function and quality of life (ideally to premorbid levels); and prevention or at least mitigation of the risks and impacts of relapse (

5,

8–

10). In addition, where applicable, ideal outcomes should include changes in lifestyle and habits to promote medical and mental health, reduce the risk of depressive relapse, and enhance resilience to life stresses. The achievement of each outcome may contribute to the achievement of the others. For example, symptom reduction and functional restoration each contributes to relapse mitigation and prevention. Problem resolution reduces symptoms and may reduce the risk of relapse. Symptom reduction may enhance problem solving and vice versa.

Challenges in the Delivery of Pharmacotherapy and Neuromodulation Therapies

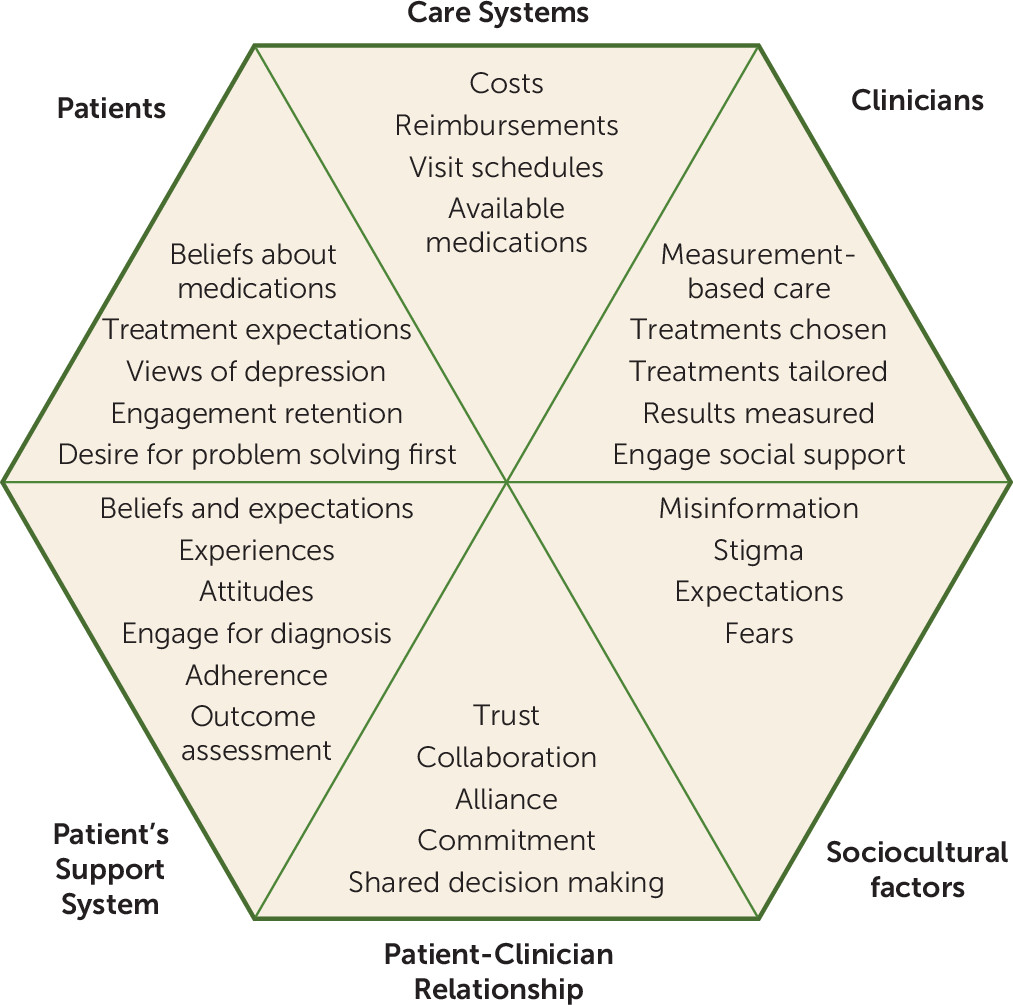

Figure 1 broadly summarizes the six main domains that can profoundly affect clinical outcomes and provides some examples for each domain. The elements in the sociocultural and care system domains are not under clinician or patient control, whereas those in the other domains are. In this article, we focus on what clinicians and patients can do to improve outcomes when medication or neuromodulation therapies are called for. Once the decision is made to initiate pharmacological or somatic treatments for a mood disorder, many challenges remain in the actual delivery of treatment to achieve optimal symptom control, functional recovery, and relapse mitigation in the real world (

5,

8,

11,

12).

Figure 2 highlights where collaboration between patient and clinician plays an essential role in the management of depressed patients—especially those who wish to avoid treatment with medications or somatic therapies. Indeed, the importance of this relationship and collaboration was emphasized by McKay et al. (

13), who used data from the 1985 National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) study that compared interpersonal therapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), imipramine plus clinical management, and placebo plus clinical management to find that when the placebo plus clinical management was compared with imipramine plus clinical management, more of the variance in depressive symptom outcome was due to the psychiatrist than to the medication, although both medication and psychiatrist contributed meaningfully. That is, the relationship context was at least as important—if not more so—than whether the patient received placebo or medication.

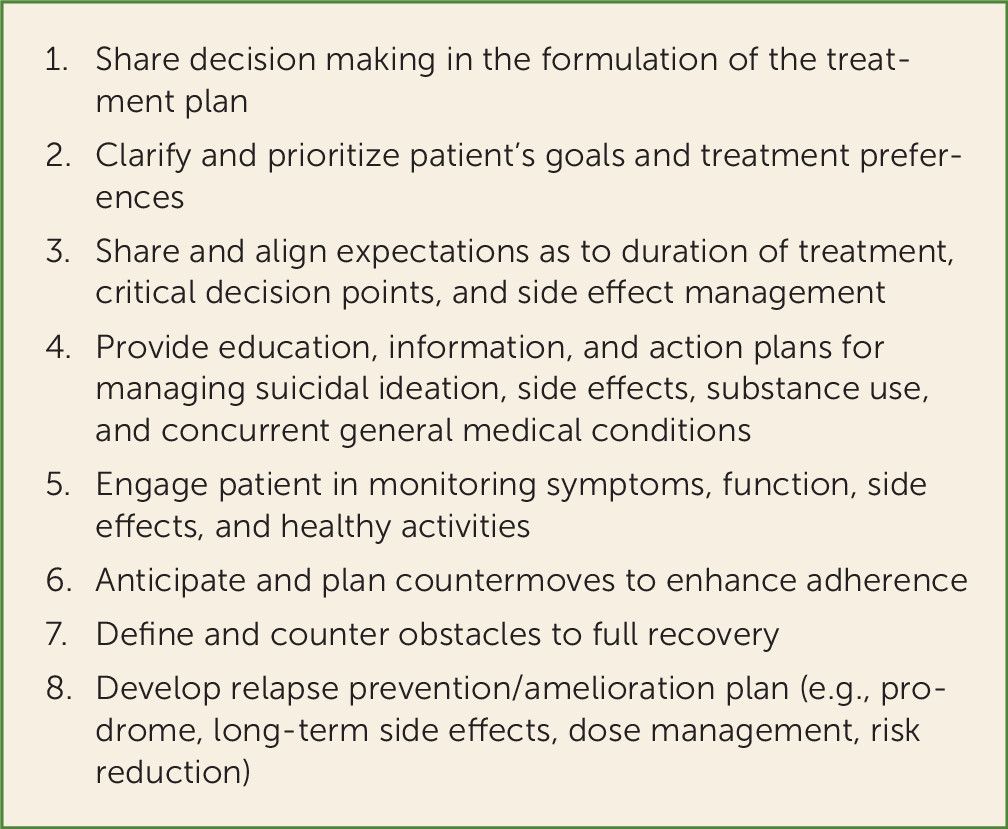

The effective implementation of patient-centered medical management depends critically on the patient-clinician relationship and collaboration. Patient-centered medical management defines and provides alternative means to address the four essential clinical tasks defined in

Table 1 in order to optimize outcomes when medication or neurostimulation is the chosen treatment. While there may be many ways to accomplish each task, there are few systematic, agreed-upon approaches regarding how to accomplish each task. Furthermore, the degree to which accomplishing each task affects symptom control, functioning, and prognosis varies widely, depending on the patient, clinician behaviors, care system factors, and incentives as well as the nature of the illness, its treatments, and other parameters.

The magnitude of these challenges is daunting. According to data from the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) study, some 10%–15% of patients will not return for treatment after an initial thorough evaluation visit; an additional 20%–35% will not complete the first acute-phase treatment step, and another 20%–50% will not complete 6 months of continuation treatment. Among patients who stay in treatment, over 50% exhibit poor adherence (

14). Because STAR*D used diligently implemented measurement-based care and provided clinical research coordinators at each clinical site (

15), these figures are likely overly optimistic for community clinical practice.

Another way to estimate the magnitude of some of these challenges is illustrated by Pence et al. (

16), who specified a depression treatment cascade analogous to the HIV treatment cascade (

17,

18). Pence et al. (

16) used available evidence to put numerical estimates on five key parameters that affect the public health impact of these steps in care. Their estimates included population prevalence of depression in primary care settings (12.5%), likelihood of depression being recognized clinically (47%), likelihood of treatment initiation (50%), likelihood of receiving adequate treatment (40%), and likelihood of achieving remission (65%). These estimates were aimed at the outcome of symptom remission (without considering functional restoration or relapse prevention). Taken together, the estimates suggest that only 6% of depressed patients in primary care settings would achieve remission in acute-phase treatment. Estimates for remission in psychiatric settings have not been made with this model.

Treatment Tasks

Each treatment task (

Table 1) is essential to optimizing the chances of recovery, and each is typically addressed in a stepwise manner, informed by the patient’s specific needs. The tasks include 1) engaging and retaining the patient in treatment (and whenever possible, the patient’s support system or persons) and optimizing adherence to both medications and behavioral changes needed; 2) selecting, implementing, and tailoring the acute treatments to optimize depressive symptom control; 3) restoring day-to-day function and quality of life; and 4) selecting and tailoring longer-term medication use, preparing for early detection of and responses to symptom exacerbations, and making lifestyle and behavioral changes that minimize the risk and personal impact of relapse or recurrence. The successful completion of each task depends on efforts by both the clinician and the patient.

Table 1 also provides a few examples of how each task could be addressed by specific clinical activities designed to accomplish it. A depressive episode within the bipolar spectrum, of course, entails the additional tasks of selecting, initiating, and optimizing a mood stabilizer.

Although these tasks are typically sequenced, they may also overlap. For example, during symptom reduction, ongoing attention is often paid to retention and adherence. And when symptoms are reduced, function usually improves as a consequence (

19). In addition, the goal of one task—for example, functional restoration—is a critical goal itself

and a means to further reduce symptoms. Furthermore, improving adherence to pharmacotherapy will minimize relapse risk, which in turn will play a key role in functional restoration and enhancing quality of life.

An iterative process is often needed to accomplish each task because we do not know which of several possible methods will be most effective for any given patient. Usually the obstacles to completing the task are defined, one of many potential methods to address a given problem is selected, and the intervention is tried. If it fails, a second step is taken. For example, a reminder system might be used to address erratic adherence. If that fails, a cognitive approach to understanding and redressing a patient’s misconceptions about medication taking may be indicated.

Obstacles to achieving these four important tasks occur at different times during the treatment process (

20), and they often require different approaches (

21). The choice of which tasks to address and when depends on patient contexts. Which methods are chosen currently rests on “clinician judgment,” informed by shared decision making. For example, some patients are already convinced of the importance of their medication treatment and have expectations that are well aligned with their likely experience, and others may have unrealistic expectations that, when not met, can lead to poor adherence or quitting treatment altogether. Engagement may be rapid for patients in the former group but require greater effort with those in the latter group. Expectations and attitudes are best addressed initially—prior to treatment initiation—to create the essential patient-clinician collaboration.

Symptom Control

After engagement, retention, and adherence, the usual next major clinical task is to optimally control symptoms while minimizing treatment side effects and, ideally, to reach sustained remission from depressive symptoms. Preferentially, this aim is most easily accomplished by using measurement-based care procedures (

51,

52). These procedures were developed and tested in the Texas Medication Algorithm Project (

53–

55) and the German Algorithm Project (

56–

61), although the term “measurement-based care” was coined when the process of measurement-based care used in STAR*D was first described (

62).

Measurement-based care enables clinicians and patients to make treatment decisions tailored to each patient through a step-by-step evaluation of treatment response and medication tolerance. After treatment initiation, the dosage is adjusted or the medication is changed to minimize side effects, maximize safety, and optimize the therapeutic benefit for each patient according to a predefined dosage adjustment plan that is informed by symptom and side effect scales administered at each visit (

62–

65).

In fact, measurement-based care procedures are analogous to the medication and placebo management procedures used in the Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program (

11), which recommended scheduled dosage adjustments informed and tailored individually by regular, systematic symptom and side effect measurements using a 47-item checklist. In 1993, the Agency for Healthcare Policy and Research Clinical Practice Guidelines for Depression (

8) also recommended a stepwise dosing process based on regular assessment of symptoms and side effects.

Relapse Mitigation

There are many potential approaches to the prevention or mitigation of symptomatic relapses or recurrences (

4,

35,

77,

78). They are best chosen for and tailored to each patient, although a systematic approach to considering and selecting among potential options has not been agreed upon, and it is not a systematic part of residency training. To address this important issue, we illustrate by way of a few examples.

Clinical experience and some data suggest that perceived resilience plays a significant role in moderating the risk of depressive onset or recurrence in high-risk individuals (

79,

80). Such findings raise the question: Can specific exercises be developed that improve resilience or help “inoculate” vulnerable individuals against the impact of stress and be used prospectively to improve the lives of those at high risk? One such group of interventions, which incorporate mindfulness-based meditation strategies, has shown some promise on both clinical (

81) and physiologic (

82) outcomes.

Furthermore, it is logical to assume that effectively treating concurrent psychiatric conditions should improve the longer-term outcomes of patients with major depression (for example, addressing panic attacks and phobic avoidance behavioral patterns may reduce relapse risk in patients with co-occurring major depression). Similarly, given the association of heavy drinking or drug use with nonrecovery from depression (

83–

86), targeted interventions that reduce or eliminate substance use disorders should enhance the outcomes of the mood disorder. Naturalistic data collected in the United States (

85) and Ireland (

87) suggest that this is indeed possible, although the uncontrolled nature of the observations leaves open the possibility that being able to reduce problem drinking or drug use is simply a good prognostic sign. As residual sleep disturbances or reemerging insomnia are associated with an increased relapse risk in major depression (

88,

89), they likewise represent a risk factor that, when treated, should be expected to improve outcomes and enhance quality of life, whether the intervention is an adjunctive pharmacotherapy (

90) or targeted CBT (

91).

The management of concurrent general medical conditions can also affect the longer-term outcomes of mood disorders. Flare-ups of autoimmune diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus (

92) and multiple sclerosis (

93), or infectious diseases that provoke neuroinflammatory responses, such as HIV/AIDS (

94) and hepatitis C (

95), increase the risk of depressive symptoms, as do some medications used to treat these conditions, including glucocorticoids (

96) and interferon-alpha (

97). Traumatic brain injuries or other debilitating conditions that profoundly reduce physical mobility and quality of life may also be treatable risk factors for depressive symptom exacerbation (

98–

100). The medications required for the management of many general medical conditions may also affect the pharmacodynamics or pharmacokinetics of antidepressant medications, and this needs to be proactively managed to reduce the risk of relapse in the longer term.

Pregnancy may increase the risk for depression. Many women planning to become pregnant may consider discontinuing previously successful antidepressant medications to avoid exposing the fetus to drugs. For them, consideration of sequential cognitive, behavioral, and interpersonal psychotherapies with established efficacy in pregnancy-related depression may be useful (

101–

103).

Prodromal detection and intervention is another approach (

10) that seems useful clinically. For example, some patients will tend toward social withdrawal, and some will develop insomnia first at the initiation of relapse, which can be countered when recognized. Others may be able to identify, for example, a particular sequence of symptoms or particular behaviors that develop when a relapse is beginning to unfold. Early recognition of these prodromes allows for early treatment adjustments or behavioral changes to mitigate the relapse.

Case example: Recognizing the signature of the relapse prodrome through the patient’s social system

“Ms. B,” a 43-year-old saleswoman with bipolar disorder who had two past hospitalizations and whose mother had bipolar disorder, was familiar with the waxing and waning of symptoms, both manic and depressive, in this condition. While treated largely with lithium (1200–1500 mg/day) and an antidepressant, Ms. B had learned to track her symptoms using a daily monitoring tool. Nevertheless, her psychiatrist encouraged her to regularly bring her husband, as a corroborating informant. On this occasion, when asked, “How are things going?” she responded that all was well and that her life and work were routine and satisfactory. When the same question was posed to her husband in her presence, he responded, “What about your visits to the all-night convenience store at 4 a.m. nearly every night in the last 2 weeks? You were talking world events and politics with the cashier. That’s new.” Indeed, without this information, we would not have recognized this prodrome. As a result, medication adjustments were made and a potential full relapse was avoided.

Corroborating informants can also play essential roles in providing the history of illness and information on treatment response and medication adherence as well as assisting in relapse mitigation (

10,

104).

Sequential or Combined Therapies With Psychotherapy

Combined treatment strategies are now widely practiced for the management of depressive disorders. A strong case can also be made for a greater use of sequential psychotherapies for higher-risk patients who have benefited from pharmacotherapy, to enhance relapse prevention, improve long-term outcomes, and optimize psychosocial functioning (

1). Although less well established, there is a literature documenting the value of focused psychotherapies to help minimize the risk of relapse or recurrence when antidepressant medications are being discontinued (

105,

106).

In addition, a recent series of studies that evaluated the utility of adjunctive psychotherapy in patients who have not responded well to antidepressant medications found meaningful levels of symptom reduction, of a magnitude comparable to those found with commonly used adjunctive medications (

107–

110).

The use of psychotherapy in combination with or in sequence with neuromodulation strategies has only recently received attention (

111,

112). And the use of therapy combined with ECT has received little attention until recently, likely in part because of the amnestic effects of acute-phase ECT, which could interfere with learning and could be disruptive to the development of a psychotherapeutic relationship, or because of a sense of therapeutic nihilism on the clinician’s part, who may judge that such patients are just “too ill” to benefit from psychotherapy.

The potential for psychotherapy to improve outcomes after ECT is no longer theoretical. One recent trial found that CBT after a course of ECT significantly reduced the risk of relapse or recurrence (compared with continuation ECT and pharmacotherapy) (

111). Moreover, the investigators found no evidence to suggest that patients’ perceptions of residual cognitive difficulties adversely affected therapeutic outcomes. Furthermore, early studies suggest that CBT may enhance or broaden the more modest antidepressant effects of transcranial magnetic stimulation therapy (

112).

In sum, there are various ways to prevent or reduce relapses, such as learning to detect early signs of relapse, avoiding or managing factors that increase the risk of relapse, enhancing social support and social relationships, and making occupational or other environmental revisions. There is a substantial need for the development and testing of a range of relapse prevention therapies in the context of pharmacotherapy or neuromodulation therapy.

Implications of Patient-Centered Medical Management

Patient-centered medical management is premised on the notion that treatment outcomes entail symptoms

plus function

plus longer-term course and that both behavioral and attitudinal changes are often required. This perspective raises several questions: 1) whether, when, and how to incorporate composite outcomes in clinical and health service research, as well as care system management; 2) whether the new methods needed to accomplish these essential clinical tasks should be based on just one or a variety of psychotherapeutic models (e.g., cognitive, behavioral, interpersonal, dynamic); 3) how to accomplish these tasks in practice; and 4) where to find research funding to develop, test, and target these new methods to accomplish these essential tasks. It is very likely that methods developed for depression will help improve the delivery of many medical and surgical treatments (

28).

The notion of composite outcomes in mental health is not new. The Agency for Healthcare Policy and Research’s Depression Guidelines Panel (

8) and others (

1,

5,

9,

11,

113) recognized that symptoms, function, quality of life, and the mitigation or prevention of relapse and recurrence were the aims of treatment, but symptoms and function are usually measured separately because they occur on different time scales. On the other hand, researchers and clinicians want to know whether some interventions with similar effects on symptoms may differ in their effects on function or prognosis. A composite measure may be quite informative at critical decision points in the longer-term management of these conditions. Alternatively, a composite measure of symptoms and function could be used repeatedly to gauge longer-term outcomes, especially in patients with waxing and waning courses of illness.

In terms of the therapeutic innovations, we currently conceptualize psychotherapies (e.g., cognitive, behavioral, interpersonal, psychodynamic) according to how we believe they work or how they explain the disorders or the problems associated with them. By contrast, medical and surgical practitioners conceptualize what they do by the objectives to be achieved. Medications, for example, are grouped according to their objectives (e.g., antibiotics, antihypertensives, analgesics), as medications in each group have different mechanisms of action. Surgeons choose among different surgical (e.g., wires, plates, joint replacement) and nonsurgical approaches (e.g., casting) to address the same clinical problem (e.g., a fractured clavicle or hip). Treatment selection is based on each patient’s situation, risk factors, personal priorities, personal burden, complication risks, occupation, and so on.

Perhaps a similar approach, at least in the case of patient-centered medical management—namely, specifying the objective to be achieved (e.g., engagement, adherence) and then selecting among possible approaches based on our understanding of the patient’s psychological and psychosocial strengths—would help us develop innovative approaches that could be tailored to each particular patient. This reframing does not exclude the development and use of the therapeutic relationship to effect change or to address difficulties caused by prior developmental difficulties or personality disorders.

Once the objective is defined, an agreed-upon metric can be selected so that diverse approaches to the same objective (e.g., adherence, relapse prevention) could be compared. For example, is motivational interviewing and shared decision making more effective in improving medication adherence than a reminder-based intervention, and if so, for which patients groups? Or we could ask which of several alternative approaches to repairing the damage done to the patient’s marriage by a recent manic episode is most effective, and for which patients. Training methods and videos to deliver these interventions could be developed and disseminated via cloud computing. This type of approach might also help improve the quality and outcomes of medical and surgical conditions, where these same four tasks pertain. Such approaches are currently being used in diabetes treatment (

114,

115).

In terms of accomplishing these tasks in practice, psychiatrists and primary care practitioners acting alone cannot deliver all aspects of the care of depression to a panel of patients. Unfortunately, the current implementation of team care in mental health clinics can marginalize psychiatrists to writing prescriptions. The system in medical and surgical clinics whereby the physician orders each major treatment task in response to an assessment of the patient’s individual level of need leaves much of the individual doctor-patient relationship intact while effectively allocating and utilizing the panoply of skills of the diverse treatment team. Requiring that each major treatment task be chosen and separately ordered by the physician encourages him or her to assess carefully each patient’s context and tailor the choices to each patient. Greater treatment effectiveness and economy would be expected by increasing the relevance of treatment to the patient.

In summary, we have identified four essential clinical tasks in the optimal delivery of pharmacotherapy or neuromodulation therapies to patients with mood disorders. Systematically addressing each task with methods specifically chosen for or tailored to each patient (patient-centered medical management) should make recovery more likely and resource utilization more cost-effective. Psychiatrists should be trained and prepared to deliver these methods themselves as well as to oversee their delivery by the relevant treatment team members. Research support to develop, test, and target innovative ways to accomplish these clinical tasks would seem to be a wise and much-needed investment.