Gun violence is a serious public health concern in the United States, with an estimated 133,895 people victimized by gun-related violence in 2017 (

1). Of the estimated 14,415 firearm-related homicides committed in 2016, approximately 31.6% were committed by adolescents and young adults ages 12–24 (

2). Among these adolescents and young adults, 22% of homicides were committed by those with previous juvenile or criminal justice system contact (

2). Given the societal cost and pain and suffering of those affected, reducing gun violence by youths is a critical public health concern.

In the most recent revisions of major classification systems for psychiatric disorders, DSM-5 and ICD-11 (

3), a new specifier, “with limited prosocial emotions,” was included within the diagnosis of conduct disorder (DSM-5) and conduct-dissocial disorder (ICD-11) to designate those youths with elevated callous-unemotional traits. Callous-unemotional traits are defined by limited guilt, reduced empathic concern, reduced displays of appropriate emotion, and a lack of concern over performance in important activities (

4). Callous-unemotional traits are found in 25%−30% of adolescents with serious conduct problems (

5), but these adolescents display more persistent and severe aggression and violent offending (

6,

7), use aggression for personal gain (

8), engage in behavior that causes more harm toward victims (

9,

10), display conduct problems that are more stable (

11), and have worse treatment outcomes (

12–

15).

However, the association of callous-unemotional traits with gun violence specifically has not been extensively examined in youths. In one notable exception, in a population-based sample of 4,855 Finnish adolescents, callous-unemotional traits were associated with a higher risk of carrying a weapon, and this effect was the largest for carrying a gun, even after controlling for other risk factors (i.e., self-reported delinquency, victimization, perceived peer delinquency) (

16). Thus, more work is needed to determine whether this association is found in other samples, especially in the United States, where gun carrying is more common, and in justice system–involved adolescents who are at high risk for gun violence (

17).

Furthermore, although this previous study controlled for key predictors of gun violence that could be confounded with callous-unemotional traits, it did not consider possible interactive effects. That is, peer gun carrying is one of the strongest predictors of adolescent gun use (

18). However, the delinquent behavior of adolescents with elevated callous-unemotional traits has been shown to be less influenced by the behavior of their peers (

19). Thus, the peer influences on an adolescent’s gun carrying may be moderated by the youth’s level of callous-unemotional traits.

Therefore, in this study we sought to determine whether callous-unemotional traits measured after an adolescent’s first arrest predicted self-reported gun carrying and gun use over the subsequent 4 years. Specifically, we hypothesized that callous-unemotional traits would predict increased frequency of gun carrying and increased probability of using a gun during a crime, even after accounting for other risk factors associated with gun use (i.e., age, race, IQ, lifetime self-reported offending, parental supervision, peer delinquency, violence exposure, impulsivity, and neighborhood dysfunction). We also hypothesized that callous-unemotional traits would moderate the relationship between peer gun carrying and ownership and participant gun carrying and use, such that adolescents who had peers who carried and owned guns would show increased gun carrying and use over the subsequent 4 years but that this effect would be found only among adolescents low on callous-unemotional traits.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

The sample included 1,215 male youths, from three regions of the United States, who were arrested for the first time. Participants were eligible if they spoke English, were arrested for an eligible offense of moderate severity, and were between 13 and 17 years of age (see

Table 1 for characteristics of the sample). Institutional review boards at all institutions approved the study procedures. Parental informed consent and youth assent were obtained at the time of assessment until the participant turned 18, at which point consent was received from the participant. Participants were informed that participation was voluntary, that participation would not influence their relationship with the justice system, that they were able to withdraw from the study at any time without penalty, and that their data were protected by a privacy certificate from being subpoenaed for use in court. Youths completed the baseline assessment within 6 weeks of the disposition date for their first arrest. They were then reassessed every 6 months for 36 months and then again at 48 months (seven follow-up assessments). Additional sample characteristics and study procedures have been published previously (

6).

Given the mild to moderate severity of the crimes committed by youths recruited into the study, very few were ever placed into detention. Specifically, 77.2% (N=884) of the sample were never incarcerated at any point in the study, 10.9% (N=133) were incarcerated for between 1 and 6 months (although not necessarily consecutively), 7.5% were incarcerated for between 7 and 12 months, and 8.7% were incarcerated for between 13 and 37 months. When participants who were incarcerated for more than 6 months across the entire 48-month follow-up period were excluded from the analysis, the results were consistent with those reported for the full sample. Thus, results of the full sample are reported here.

Main Variables

Callous-unemotional traits.

Callous-unemotional traits were assessed at baseline using the self-report version of the Inventory of Callous-Unemotional Traits (

20). This 24-item instrument has been positively associated with antisocial behavior and negatively associated with prosocial behavior across a range of adolescent samples (

21). The internal consistency for the baseline total score on the Inventory of Callous-Unemotional Traits (mean=26.27, SD=8.08) in this sample was acceptable (Cronbach’s alpha=0.76).

Peer gun carrying and ownership.

Peer gun carrying and ownership were assessed at baseline using two items from the Association With Deviant Peers Scale (

22). Participants were asked how many of their friends have “carried a gun” and “owned a gun” (responses range from 1 [“none of them”] to 5 [“all of them”]).

Gun carrying and use.

Self-reported gun carrying and use of a gun during a crime were assessed at each of the seven follow-up time points using one item from the Self-Report Offending Scale (

23). Each item asked participants (yes=1 or no=0) if they had carried a gun at any point since the last interview, and if yes, how many times. A total gun carrying variable was created for the purpose of this study by summing the number of times participants endorsed carrying a gun across all follow-up time points. Self-reported gun use during the commission of a violent crime was also assessed using the Self-Report Offending Scale. Participants were asked (yes=1 or no=0) if, since the last interview, they carjacked someone, shot someone, shot at someone, committed armed robbery, participated in gang violence, or killed someone. If participants endorsed engaging in any of these offenses, they were then asked if they used a gun (yes=1 or no=0). Because of the low base rate of this variable (8.1% of the sample reporting having used a gun during the 48 months after first arrest), a dichotomous variable was used to represent use of a gun at least once during the follow-up period.

Baseline Control Variables

To assess demographic control variables, participants’ self-reported age and race/ethnicity were collected. Race/ethnicity was dichotomized such that endorsement of the ethnicity or race was coded as 1, and no endorsement was coded as 0 (i.e., 1=black, 0=not black, 1=Latino, 0=not Latino). Intelligence was assessed at baseline (mean score=88.43, SD=11.59) using the matrix reasoning and vocabulary subtests of the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (

24). Self-reported lifetime offending prior to a first official arrest was assessed at baseline using the Self-Report Offending Scale (

23) by asking adolescents if they ever in their life engaged in a variety of illegal behaviors (Cronbach’s alpha=0.76). Items include a range of antisocial behaviors of various types and severity, including “purposely set fire to a house, building, car, or vacant lot,” “been in a fight,” “forced someone to have sex with you,” “stolen something from a store,” and “gone joyriding.” The measure also included three questions related to gun use prior to a first arrest, including “carried a gun,” “shot at someone, where you pulled the trigger,” and “shot someone, where the bullet hit the victim.” Peer delinquency was assessed at baseline using the Peer Delinquency Scale (

22), which asks youths to state how many of their friends have engaged in illegal behaviors (Cronbach’s alpha=0.93). To reduce redundancy, we calculated the total peer delinquency score using 11 items, removing two items related to peer gun carrying and ownership. Exposure to violence was measured at baseline using the Exposure to Violence Scale (

25), which asks participants if they were victimized by five different types of violence or witnessed someone else victimized by violence. Impulse control was assessed at baseline using the eight-item self-report impulse control subscale of the Weinberger Adjustment Inventory (

26) (Cronbach’s alpha=0.73). Parental supervision was measured at baseline using the Parental Monitoring Inventory (

27), which assesses how much the caregiver tried to know and actually knows about domains of the adolescent’s life and how often the caregiver required various forms of curfew (Cronbach’s alpha=0.78). Neighborhood disorder around the adolescent’s home at baseline was measured using 21 items to assess the physical disorder and social disorder of the neighborhood (Cronbach’s alpha=0.94) (

28).

Statistical Analysis

Multiple imputation was conducted in SPSS, version 25 (IBM, Armonk, N.Y.), using regression-based imputation, with 20 imputations (

29). All variables, including covariates, were used in the imputation. The data were missing completely at random (χ

2=106.48, df=112, p=0.63). Eight variables had no missing data, and eight variables had some missing data. The percentage of missing data across these variables ranged from 5.3% for parental monitoring to 0.4% for peer delinquency. Among all participants (N=1,215), 11.6% (N=141) had some missing data, which led to 0.77% of all values missing.

To test the main hypotheses, we conducted a series of negative binomial and Firth logistic regression analyses, all of which were two-tailed tests. Negative binomial regressions were utilized when predicting total self-reported gun carrying because this variable was a count with a large number of “0” values, and it followed a skewed, overdispersed distribution, such that the variance of the dependent variable was greater than the mean. Further, as noted above, none of the participants were unable to engage in gun carrying or gun use across the entire follow-up period, and only a few had a reduced opportunity due to short periods of detention. Firth logistic regressions were utilized when predicting self-reported gun use during the commission of a violent crime and arrests for gun-related crimes because of a low base rate of endorsement of these crimes. Firth logistic regression, conducted in

R, uses penalized likelihood, which reduces bias in the prediction of low base rate events in maximum likelihood estimation (

30). Callous-unemotional traits, peer gun carrying, and peer gun ownership were mean centered and, with their interactions, entered as independent variables.

Results

Callous-Unemotional Traits Predicting Gun Carrying and Use of a Gun during a Crime

To assess whether callous-unemotional traits would predict the frequency of gun carrying after a first arrest, we conducted negative binomial regressions. The analysis revealed a significant main effect of callous-unemotional traits (B=0.078, SE=0.004, p<0.001, 95% CI=0.071–0.086). As shown in

Table 2, this result remained even after controlling for other known risk factors, including age, IQ, race/ethnicity, self-reported offending prior to first arrest, impulse control, parental monitoring, neighborhood dysfunction, exposure to violence, and peer delinquency. After controlling for covariates, every one-point increase in callous-unemotional traits was associated with a 7.6% increase in the likelihood of carrying a gun.

Next, we conducted a Firth logistic regression to test the prediction that callous-unemotional traits would increase the probability of using a gun during the commission of a serious crime within the 48 months after a first arrest. Again, the analyses revealed a main effect of callous-unemotional traits (B=0.102, SE=0.014, p<0.001, 95% CI=0.075–0.130) that remained significant after controlling for covariates (see

Table 2). Specifically, with every one-point increase in callous-unemotional traits, there was a 6.9% increase in the probability of using a gun during a violent crime, after accounting for the covariates.

Callous-Unemotional Traits as a Moderator of the Association Between Peer Gun Carrying and Ownership and Adolescent Gun Carrying and Use

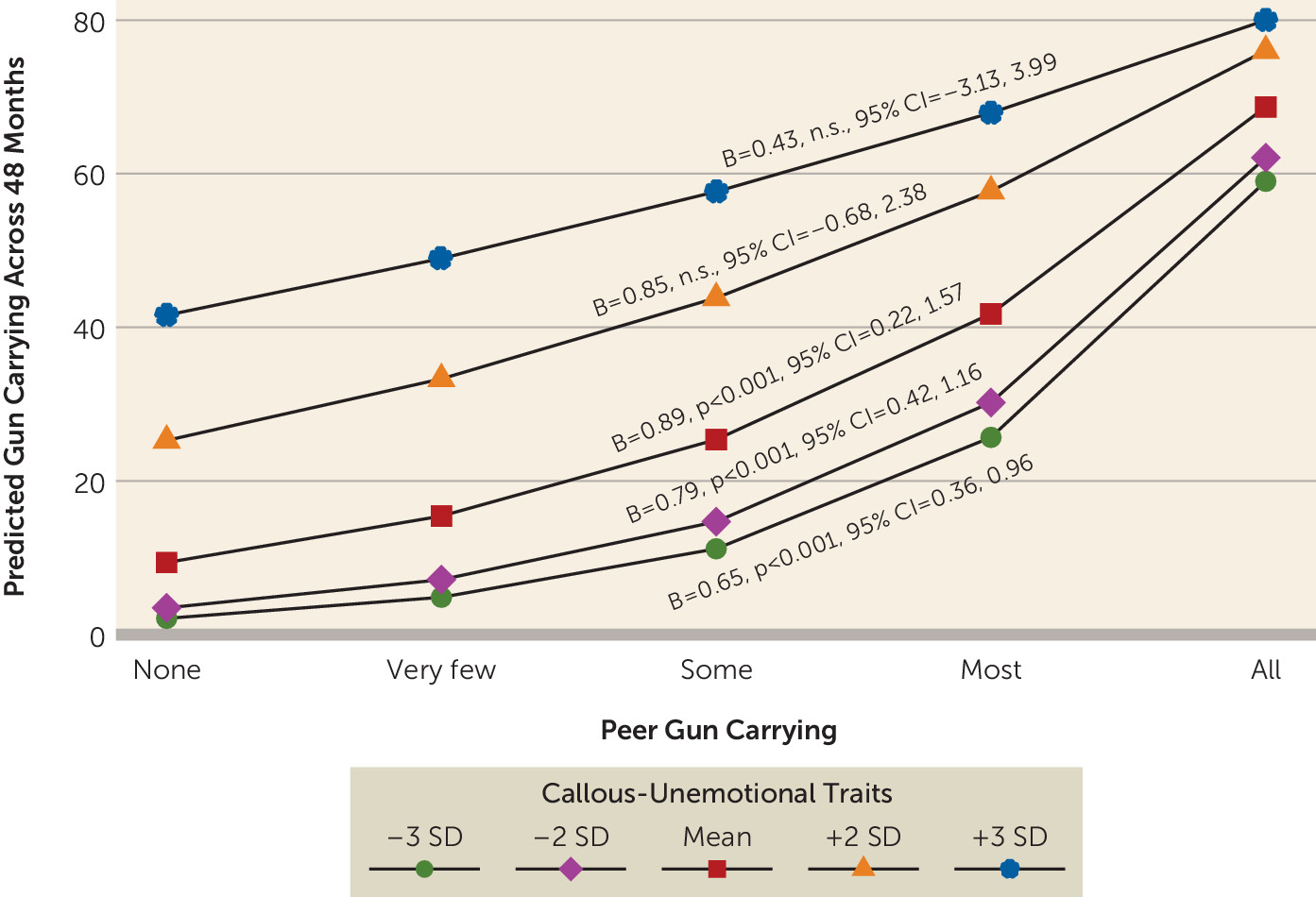

To examine whether callous-unemotional traits would moderate the relationship between peer gun carrying (and peer gun ownership) and participant gun carrying, we ran two separate negative binomial regressions, first with callous-unemotional traits, peer gun carrying, and their interaction and then with callous-unemotional traits, peer gun ownership, and their interaction. For both analyses, there were conditional effects for callous-unemotional traits and for peer gun carrying and ownership, and a significant interaction. As indicated by the regression coefficients in

Table 3, the form of this interaction was the same for both variables. Thus, we plotted only the interaction with peer gun carrying in

Figure 1. Specifically, we calculated and plotted the marginal mean differences in peer gun carrying across levels of callous-unemotional traits in the prediction of total gun carrying across the 48-month follow-up period. As predicted, peer gun carrying led to increased adolescent gun carrying only at low to average levels of callous-unemotional traits. That is, at scores below, but not above, 42 on callous-unemotional traits, or two standard deviations above the mean, the association between peer gun carrying was significantly related to adolescent gun carrying.

Firth logistic regression analyses were conducted to test the prediction of use of a gun during a crime following first arrest (

Table 3). Again, there were main effects for callous-unemotional traits and both peer gun variables (carrying and ownership), but the interaction was not significant (p<0.06) for callous-unemotional traits and peer gun carrying. Although not significant, the coefficients indicate a form of interaction similar to that reported in

Figure 1.

Discussion

With the addition of the “with limited prosocial emotions” specifier within the diagnosis of conduct disorder (DSM-5) and conduct-dissocial disorder (ICD-11) (

4), we sought to examine the role that callous-unemotional traits may play in the risk for gun carrying and gun use during a violent crime in a sample of justice system–involved adolescents, a group at high risk for this serious public health concern.

Our results suggest, first, that callous-unemotional traits measured shortly after adolescents’ first arrest predicted increased frequency of gun carrying and a higher likelihood of using a gun during a violent crime across the subsequent 4 years. Importantly, this relationship remained after accounting for other risk factors associated with both callous-unemotional traits and gun use. These findings align with a substantial amount of previous research suggesting that callous-unemotional traits are a risk factor for severe delinquency, violence, and recidivism (

4,

7). Our results suggest that callous-unemotional traits need to be considered as a risk factor specifically for gun use in arrested adolescents, who are at particularly high risk for gun use (

31).

Second, our results indicate another reason to consider callous-unemotional traits in research on gun use in adolescents. Callous-unemotional traits moderated the relationship between peer gun carrying and ownership and adolescent gun carrying, such that only participants low on callous-unemotional traits demonstrated increased gun carrying as a function of their peers’ gun carrying and ownership. Similar interaction effects approached significance in predicting gun use during a crime. Thus, adolescents with elevated callous-unemotional traits appear to carry and use guns at higher rates, regardless of gun carrying and ownership by their peers, consistent with previous research suggesting that these adolescents may be less susceptible to peer influences (

19). Further, past research linking peer gun use with adolescents’ own gun use may have underestimated the effect of peers for the majority of youths, who do not have elevated callous-unemotional traits (

20). However, it is important to note that compared with other predictors, the effect size for callous-unemotional traits predicting gun carrying is smaller than many other covariates (e.g., lifetime offending, exposure to violence). Thus, research should continue to study, and interventions should continue to target, these other predictors as well.

Although this study has multiple strengths, including the longitudinal design and use of a large, diverse sample of adolescents from three geographically distinct regions of the United States, it is not without limitations. First, our sample included only male participants, and although there is evidence to suggest that males are more likely to be elevated on callous-unemotional traits (

32) and own guns at an earlier age (

33), further research should attempt to replicate these findings in females. Second, while a sample of justice system–involved youths is considered a strength because of the higher rate of gun carrying in such samples, it can also be viewed as a limitation because of the limited generalizability of these findings to community-based samples. With this in mind, further research should investigate the effect of callous-unemotional traits and peer gun use on adolescent gun carrying and use in general populations. Third, we relied on the youths’ self-reported gun use. This method is justified in that the vast majority of gun carrying and gun use by adolescents goes undetected by authorities and is typically not known by others (e.g., parents, teachers) (

34). However, this method does lead to shared method variance between our key predictor (i.e., callous-unemotional traits) and outcome, which may have inflated associations.

The present study has important implications regarding the risk factors for gun carrying and use in adolescent boys in the juvenile justice system. First, interventions to reduce gun violence need to consider methods that have proven effective for youths with elevated callous-unemotional traits (

12), who often do not respond as well to traditional mental health treatments (

13–

15). Second, our findings demonstrate the importance of considering callous-unemotional traits in future gun violence research because they may moderate the influence of other known risk factors, such as peer gun use, and lead to underestimates of the impact of this risk factor in the majority of youths, who do not have elevated callous-unemotional traits.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the many research assistants involved in data collection across the three study sites; the youths and their families for their participation; and the agencies that funded the Crossroads Study, including the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the William T. Grant Foundation, the County of Orange, Calif., and the Fudge Family Foundation.